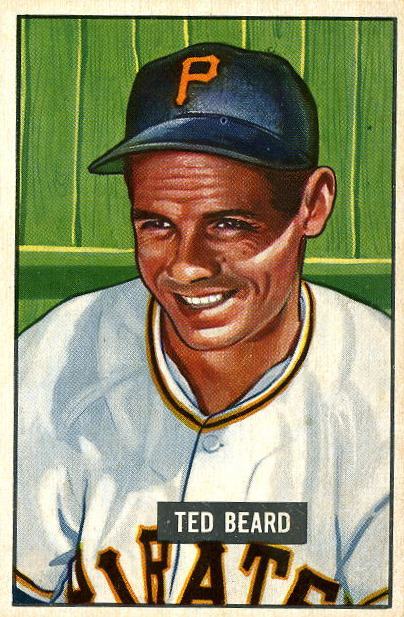

Ted Beard

It took a tremendous blast to hit a home run over the 86-foot high right field roof at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. From the time of the roof’s construction in 1925, until the stadium’s final game in June 1970, only 19 balls, hit by 10 different players[1], ever cleared the roof. Among the men who accomplished the feat were some of the most prodigious sluggers of all time: Babe Ruth, whose homer was the 714th and last of his legendary career; Willie Stargell, who did it a record seven times; and Eddie Matthews, who homered twice. And then there was Ted Beard; in the company of power hitters such as those, he was the most unlikely slugger of them all.

It took a tremendous blast to hit a home run over the 86-foot high right field roof at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. From the time of the roof’s construction in 1925, until the stadium’s final game in June 1970, only 19 balls, hit by 10 different players[1], ever cleared the roof. Among the men who accomplished the feat were some of the most prodigious sluggers of all time: Babe Ruth, whose homer was the 714th and last of his legendary career; Willie Stargell, who did it a record seven times; and Eddie Matthews, who homered twice. And then there was Ted Beard; in the company of power hitters such as those, he was the most unlikely slugger of them all.

During the twenty-one years he spent on his family’s farm in the rural mid-Maryland community of Woodsboro, it’s highly likely that at some point young Cramer Theodore Beard met Archie Stimmel, the only other player from the small town ever to reach the major leagues. As a pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds from 1900 to ’02, Stimmel compiled a 5-19 record in 26 games. He lived his whole life in Woodsboro, “almost to the end,” wrote the press upon his death in 1958, at age 85, “in the same home [where] he first saw the light of day.” (Stimmel was laid to rest at Woodsboro’s Mount Hope Cemetery.) Well known about town as a raconteur of his deadball-era days, Stimmel, who lived on Main Street in the center of town, was 47 years old when Beard was born, on January 7, 1921. It’s intriguing to envision the budding baseball star sitting at the feet of the old man, listening with rapt fascination to his tales. (Just 20 miles southwest of Woodsboro, in Middletown, Maryland, Charlie Keller, five years older than Beard, was growing up on his family’s farm.)

As the youngest of four children, Beard’s childhood was beset by tragedy. According to his wife, Laura, Beard was seven when his mother, Maude, died of tuberculosis. Soon thereafter, when Beard was between seven and ten years old, the eldest child, Elwood, died accidentally at age 13. So Beard grew up with his father, Raymond, and two sisters, Louise (known as Dolly), and Pauline. Raymond, who never played baseball, spent most of his life as a farmer, but before his death in 1958 he also worked at a foundry in the nearby town of Frederick. Coincidentally, Raymond passed away the same year as Archie Stimmel. (In a 1993 interview for the SABR Oral History Committee, when asked about his family’s reaction to his signing a major league contract in 1942, Beard remembered that “they liked it; of course, I only had my father and two sisters at the time.”)

About Beard’s formative years there are some questions. According to most baseball references, he attended Walkersville High School, five miles west of Woodsboro; as Woodsboro had no secondary school of its own, children traveled to the larger town. However, Beard’s name doesn’t appear in Walkersville High School box scores in any years preceding 1942, so it’s unclear whether he played varsity baseball. In his SABR interview, though, Beard stated that he “played a lot of sandlot ball”; also, at the time of his signing, the press wrote that Beard “had made good in county, amateur and semi-pro leagues.” Regardless, by 1941 the 20-year old was the cleanup hitter for Woodsboro in the eight-team Maryland State League[2]. Alternating defensively between the outfield and pitcher, that season Beard led the team to a championship, upsetting the regular season pennant winner, Point of Rocks, in a best-of-three series. In the press’s post-season analysis it was noted that “Beard turned in a good pitching record for Woodsboro.” With both a strong left arm and some pop in his bat, Beard proved crucial to Woodsboro’s fortunes. Soon, however, his own fortunes were dramatically changed.

As 1942 began, Beard intended to return to the Maryland State League, this time as Woodsboro’s player/manager. Yet as April got underway, two stories appeared in the press on consecutive days, each of which directly involved his future. On April 6 came an announcement of the opening in Frederick of a Pittsburgh Pirates baseball school, to be held by “Poke” Whalen, manager of the Pirates’ Class D team in Hornell, New York. The following day the press related that at the behest of manager “Lefty” Beard, all Woodsboro players were to report to the town diamond the following Sunday, April 12, for the season’s first practice. Beard never kept that date. At the urging of his cousin, over the next week Beard hitch-hiked 10 miles each day to Frederick and attended the Pirates’ tryout camp. Whalen liked what he saw, offered the young man a $75 per month contract (“after a month,” Beard later recalled, “they gave me a raise– to $80”), and Beard subsequently resigned as Woodsboro’s manager. The 21-year old quickly set off to begin his professional career.

With the exception of three years in the military, that career lasted for the next 19 seasons. If Beard never ultimately realized lasting success in the major leagues (he played just 194 games over parts of seven seasons), he nevertheless enjoyed great success in the minors (1,915 games). As with many players, the transition from Triple A to the majors proved a challenge that Beard was never quite able to overcome, yet he produced several dominant seasons at the lower levels, including a number of performances that surpassed his most notable major league achievement.

For a player who will be forever renowned for a singular display of power, Beard was surprisingly small: just 5’ 8” tall and 160 pounds. A left-handed hitter, he was by his own admission “mostly a line drive hitter; more or less a contact hitter.” He also possessed two physical skills that would have immediately impressed Whalen—outstanding speed and a tremendous throwing arm. Although he had been a versatile defender for Woodsboro, there were no doubts about which position he would play as a professional. After watching Beard perform at the tryout camp, Whalen explained to the press, “There is no limit to where Beard may go, but he will always be an outfielder.” So throughout his career, Beard always batted near the top of the order and roamed either center or right field. Many years later, Beard recalled, “Outfield was the only position I ever played [as a professional]. I was too small for first base. I would like to have pitched. My first year, we were a little short of pitchers. I told the manager, ‘I’ll pitch a game.’ He said, ‘I would, if I had another reindeer in the outfield.’ He wouldn’t let me pitch.”

Within days of his signing, Beard reported to Hornell and immediately became the leadoff hitter and starting center fielder for the PONY league club. That initial foray into professional ball lasted 80 games; in late August, when “Poke” Whalen was released as manager at Hornell, Beard was promoted to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in the Class B Interstate League, where he played his final 20 games of the 1942 season. (At least one of those was played in Hagerstown, Maryland, just 35 miles from Beard’s Woodsboro home.) But on September 1, 1942, Beard was drafted into the Army, so almost before it began, he was forced to place on hold his nascent career. It would be three years before Beard could once again be paid for his chosen profession.

On January 7, 1943, Beard celebrated his 22nd birthday. By then he was stationed at Fort Shafter, in Honolulu, Hawaii, where he was trained as a medic. He wasn’t the only ballplayer on the island.

“I played on the Fort Shafter team,” Beard recalled. “I played with and against,” established major leaguers. “Had a lot of fun; I enjoyed it.” Among the players Beard remembered, “Johnny Mize and Hugh Mulcahy were on one team. Joe DiMaggio and Red Ruffing were on another. Mulcahy managed a team over there. He had Ferris Fain… I played against him.” Beard remained at Fort Shafter until the invasion of the Philippines, during which he served as a medic in the Pacific theatre. By the time he was finally discharged, he was 24 years old.

The next two seasons put Beard firmly on the Pirates’ radar. It was at York, Pennsylvania, that he came into his own. By 1946, the Pirates, who still held Beard’s contract, had relocated their Class B team from Harrisburg to York. Upon his discharge from the Army early in ’46, Beard joined that club. With only one professional season under his belt (1942), he hadn’t had much time to ply his craft; nonetheless, he put together two outstanding campaigns.[3] Over that time he displayed excellent bat control and patience at the plate (consecutive .320 batting averages with over 100 walks each season), impressive power (consecutive slugging averages over .540), and also excellent speed (17 stolen bases in ’46, and a league-leading 33 in ’47), all while providing sterling outfield defense. Those performances proved Beard was ready for a larger stage, and he found it in 1948.

The 1948 Indianapolis Indians, the Pirates’ Triple-A club in the American Association, were one of the best teams in the history of the minor leagues.[4] Beard had first joined the team the previous September at the conclusion of his second outstanding season at York, but in two games he batted just once and never got on the field defensively. So, 1948 effectively marked his debut with the team with which he would forever after be identified. In November 1979, readers of the Indianapolis News selected Beard as right fielder on the All-Time Indianapolis Indians All-Star team, ahead of both Rocky Colavito and Roger Maris.

The league’s regular season pennant chase provided little drama. After winning 12 of their first 15 games, a slump in May caused manager Al Lopez’s team to briefly relinquish first place; eventually, though, their 100-54 record proved 11 games better than their closest rival, and the team cruised to Indy’s first championship in 20 years. Beard’s play was crucial to the team’s success. After beginning the season with a 13-game hitting streak, he was one of seven Indians named to the league’s All Star team, and he finished as the league-leader in triples (17), runs scored (131) and walks (128)[5]. Moreover, he also batted .301, with 85 RBI from the top of the order.

Yet for all Beard’s offensive accomplishments, he may have been even better defensively. That year, Indians’ fans gave Beard a nickname that required little elaboration: he was called, simply, “The Arm.” Routinely cutting down runners with strong and accurate throws from right field (Pirates’ manager Bill Meyer would later boast that Beard was the most accurate left-handed thrower in the National League), Beard amassed an astounding thirty-one outfield assists. Almost fifty years later, he recalled, “I threw one base runner out three times in one game… can’t remember the name, but it was the shortstop for Minneapolis. I threw him out twice going from first to third and once from second to home. Every time I’d go into Minneapolis the sportswriters would mention it.” That kind of performance rarely went overlooked. As it turned out, the Pirates’ front office had been watching all along. [6]

As the Indians battled for the American Association pennant, the Pirates, who were in their own pennant race and in search of defensive help in the outfield, were reluctant to promote Beard to the major leagues; management preferred he remain in Indy until the Indians won the pennant. However, by September 4, with Indy having clinched the title and the Pirates just three games out of first, Pirates’ president Frank McKinney announced Beard’s immediate recall.

“It is only fair to the Pittsburgh players,” McKinney explained, ”who have a chance at some world series [sic] money, that we can help them if we can, and Pittsburgh definitely needs an outfielder who can catch a ball. We have been weak in right field all season and we believe that Beard will be the man to strengthen the club in its drive to a first-division berth.” So Beard boarded a train in Indianapolis and headed to Forbes Field.

He made his debut the following afternoon. On September 5, the Pirates hosted the Cubs in a doubleheader, and Beard started both games in center field. Batting third, ahead of Ralph Kiner, he tripled in each game and also drew two walks and stole a base. In the field, he handled seven chances flawlessly. Afterward, the press waxed nostalgic in its praise:

Beard “looked like Lloyd Waner,” wrote the Associated Press. “He raced around the base paths like a grayhound chasing a mechanical rabbit and all but catching up with it. In his first time at bat, he walked and promptly stole second. In his next appearance Meyer gave him the sign to hit the ‘cripple’ and Ted lashed it 400 feet off the right field wall for a triple; in the second game of the doubleheader, another triple. Chicago manager Grimm gave him a pat on the back as the teams left the field. Ted’s speed confounded the opposition.”

Yet accolades of that type were short-lived. For while he remained the Pirates’ starting center fielder for the remainder of the season, Beard managed just fourteen more hits and finished with a .198 batting average; his OPS was an abysmal .600. Nevertheless, as the season ended the Pirates announced Beard’s addition to their roster for 1949. In a brief stint of twenty-five games he had proven to be a major league caliber outfielder. It remained to be seen, however, whether he could also be a major league hitter.

The next four years proved that he wasn’t, although by all accounts manager Meyer gave him every opportunity to become a regular. Over the four-year period from 1949 to ’52, the Pirates were a dreadful team, amassing a combined record of 234-381(.380), so Meyer was usually desperate for help throughout the lineup. During that time Beard competed with the likes of Tom Saffell, Wally Westlake and Gus Bell for time in the outfield, yet he never managed to hit well enough to claim a permanent position. From 1949 to ’51, he began each season with the Pirates but ended each year with Indianapolis. The first time Meyer sent Beard down, in May 1949, he claimed Beard had “too much natural ability to be shunted aside.” In fourteen games Beard had batted just .083. The next year Beard’s spring performance made him “the talk of the Steel City’s NL entrants,” but by mid-July, with just a .232 average and .689 OPS, Meyer merely hoped that Beard “may begin hitting well enough to alternate in centerfield with Westlake.” It probably didn’t help when the hometown Frederick News-Post observed that same spring that for Beard, “at age 29, it’s now or never.”

If Beard ever felt pressured by those kinds of opinions, he likely kept his feelings to himself. During his time with Pittsburgh he was one of seven bachelors on the team, and whether or not he developed close friendships with any of his teammates is unclear. In his SABR interview, however, Beard alluded to a friendship with Wally Westlake.

“I used to hunt squirrels in the fall of the year,” Beard said. Westlake, too, “liked to hunt, like I did. He called me ‘Squirrel Hunter.’”

It’s unclear whether the two ever hunted together, but it appears that Beard was rather adept with a rifle. In August 1947, The Frederick News reported that there were “several outstanding trap artists from Woodsboro prominent in local and Mid-Atlantic competition… Ted Beard, among other Frederick County top-flight marksman, was active in traps the last two seasons.” Growing up on the farm, it seems he was practicing more than just baseball.

By 1950, the year of his signature home run, it appeared Beard might finally be developing as a hitter. For the first time as a major leaguer, he was in the lineup on Opening Day, starting in right field. Two days later, on April 20 at St. Louis, in a preview of his more famous shot, Beard, batting leadoff, hit the first pitch of the game from Cardinals’ pitcher Howie Pollett onto the right field pavilion roof in Sportsman’s Park (it was 354 feet down the power alley to the pavilion). By May 12, he had started twenty-one games and had a .241 batting average and .721 OPS. Then he got hurt. That day, at Wrigley Field, while running from first to second trying to break up a double play, a throw from shortstop Roy Smalley struck Beard’s right hand and fractured his wrist. He was out of the lineup until June 20. Upon his return he was shifted defensively to center field, and on July 16 Beard became the second man (after Babe Ruth) ever to hit a home run over Forbes Field’s right field roof.

In his SABR interview, Beard downplayed his signature homer, stating, “I didn’t hit many home runs (only six in 474 career major league at bats). I hit one out at Forbes Field, but that was an accident.” Given his home run earlier that season in St. Louis and the 363-footer he’d hit in 1946 with the Minneapolis Millers (see note 3 below), it had to have been more than accidental. On the mound for visiting Boston that day at Forbes Field was a tall right hander named Bob Hall, making the fourth of four starts in a season during which he would finish with a record of 0-2 and a 6.97 ERA. In 2006, the 85-year old Beard told the New York Times, “the first time that game I hit a line drive to second base, and the second baseman caught it. Then I hit a line drive to right field, and the right fielder caught it. The third time I got it over the roof. I didn’t know it would go over the roof. I thought it would go in the upper deck. It was a pretty good shot for a little guy like me.”

Ultimately, though, Beard didn’t produce enough “good shots.” The Pirates finally gave up on him in 1952. That season Pittsburgh installed 19-year old Bobby Del Greco, a Pittsburgh native, in center field, flanked by Ralph Kiner and Gus Bell. With veteran George Metkovich also on the roster, the 31-year old Beard was the odd man out. After briefly returning home in April, where it was announced “Beard… will be in centerfield when the Woodsboro nine meets the Union Bridge [Maryland] colored All-Stars at Woodsboro,” he again opened the season with the Pirates, but by May 8 he had made only fifty-two plate appearances in fifteen games. The next day the press announced, “Beard has been released outright to Hollywood” of the Pacific Coast League. After just 137 games, his National League career was ended.

On the West Coast, however, he again thrived in the batter’s box. Indeed, Triple-A pitching rarely posed a problem for Beard. In May ’52, he arrived in Hollywood in plenty of time to help lead the Stars to their second PCL pennant in four years. And then came 1953.

In Frederick, Maryland, the Frederick County Recreation Department houses the Frederick County Sports Hall of Fame.[7] Beard was named to the Hall in 1978, the second year of the Hall’s existence. (The previous year, Charlie Keller was a member of the inaugural class. Archie Stimmel gained admission in 1982; and Hal Keller was named in 1984.) Among the sports memorabilia displayed at the Hall is the small bronze medallion that Beard received from the Helms Athletic Foundation in June 1953 as “Southern California Athlete of the Month” for April of that year. It was well deserved, as Beard put on an impressive batting display during the first month of the 1953 season. First, on April 4, at San Diego, he set a PCL record by hitting four home runs in one game: in a 6-5 victory he went four for five, driving in all six runs with home runs, all hit to right center field, 375 feet away. Later in the month he then tied another record when he went 12 for 12, collecting five home runs, a double and six singles, before ending his string with a fly out. Following that out, he then collected two more singles. His performance helped the Stars once again claim the league title.

As 1954 ushered in Beard’s 33rd birthday, it also ushered in two significant changes in his life. The second wouldn’t have happened without the first. As the season opened, Beard was once again in the outfield for Hollywood. However, after appearing in just two games, on April 8 he was sold to the San Francisco Seals for cash (an amount reported by the press at the time as “around $5,000” but which Beard later remembered as $10,000).

“Hollywood was loaded with outfielders,” Beard remembered, “and San Francisco needed a lot of help. They were just picking up players. They bought my contract and I went to San Francisco. I was expendable.”

He made an immediate impact. In May, during a 15-7 victory over Portland, he tied the PCL record for putouts by an outfielder, recording eleven in center field. By June, San Francisco had won 24 of 29 games, and Beard, whose “hitting, fielding and daring base running ha[d]set the pace for the Seals frisky youngsters,” deserved much of the credit. He was named a reserve outfielder on the PCL All-Star team, and when team president Damon Miller was later asked about Beard’s acquisition (called by the press “the steal of the year”), he responded, “It was a gamble and we’re glad we took it.”

Clearly, Beard was too. For that year he met his future wife, Laura. She was working at the San Francisco stadium as an usherette, and when I spoke with her in October 2010, she and Ted had been married 56 years. They have three children, Robin, Raymond Theodore (Ted) and Steven; two grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

Clearly, the “steal of the year” worked out well for everyone.

Beard spent two full seasons in San Francisco, but his 1955 performance declined dramatically from the previous year. Still, he prepared to return to the Bay area for 1956. As the season approached, however, Beard remembered, “the Red Sox changed their working agreement from Louisville to San Francisco [San Francisco had previously been unaffiliated]. They wanted me to cut my salary too much and I wouldn’t sign with them… I was making $1,250 a month and they wanted to cut me to $1,000 and I wouldn’t take it. So I came to Indianapolis [he had moved there in the winter of 1949] to see [owner] Ownie Bush and Hump Pierce. Hump said, ‘You want to play for Indianapolis? I said, yeah, if you pay me enough money. Two days later,” he continued, “I got notice that my contract was sold to Indianapolis.” His salary was $1,100.

That year he roomed with Roger Maris. In 1993, Beard recalled, “When Cleveland took Roger up [in 1958], Roger was having a bad year. I run into him in Baltimore [Beard was briefly with the White Sox that season]. I said, ‘Roger, what’s the matter; everybody in Cleveland telling you how to hit?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you go tell them to go shut their yap?’ I guess he did and they sold him to Kansas City. I knew when he went to KC he was on his way to the Yankees.”

For the next year a half in Indy, which now had a working agreement with the Chicago White Sox, Beard proved that at age 36, he hadn’t lost a step. Little could he have known he was about to return to the major leagues. If he had been contemplating retirement (Beard “bought himself a lime spreading truck and was thinking about hanging up his spikes to operate a business around his native Woodsboro,” the press reported in March 1956), then events soon dictated a change in plans. After a sizzling 96 games with Indianapolis in 1957 (.347/.454/.559), during which he was named to the American Association All-Star team, on July 23 the White Sox recalled Beard to replace struggling outfielder Ron Northey as a defensive specialist and pinch-hitter. The White Sox, managed by Beard’s former manager, Al Lopez, were contenders, and Beard was just the veteran presence they needed on the bench. (His $10,000 salary, Beard later remembered, was the highest of his career.)

On May 9, 1958, Beard recorded the 94th, and final, hit of his major league career. Fittingly for the man who hit one out of Forbes Field, it was a home run. On May 14, he was optioned back to Indianapolis. Later, in September, he was recalled by Chicago to report to spring training in 1959, but on October 13, he was released outright to Indianapolis. His major league career was over.

From 1958 to ’60, Beard played 340 more games for Indianapolis. But at the conclusion of the ’60 season, he knew his career was finished.

“In 1960,” he recalled, “I’m 39 years old. I know my arm’s dead and I know there’s balls hit out there that I– I know I’m going to catch as soon as they leave the bat and I can’t get within one or two steps of them. So after the season was over, Ownie Bush called me and said, ‘You can’t play anymore.’ I knew I was done, but you hate to admit it. So that was the end of my playing days.”

That season, on July 5, with the club in last place, Beard replaced John Hutchings as Indy’s manager (Beard became player/manager) and guided them from last place to seventh; his record was 35-40. In November 1960 he was offered the chance to return as player-coach for 1961 but resigned to become manager at Class A Columbia, in the South Atlantic league. (That year both Indy’ and Columbia were Cincinnati Reds’ affiliates.) Yet after beginning the season at Columbia, on July 6, with the club in sixth place, he resigned, and returned to Indy as a coach, where he remained for most of the next six years. After coaching in the White Sox minor league system for several years, Beard retired from the game following the 1972 Rookie League season in Sarasota.

Beyond the game, Beard also had several civilian jobs. For two years he worked for the WHS electric company in Indianapolis, until he was laid off from his union position on Christmas Eve, 1974. Then in June 1975 he went to work on the highway crew for the State of Indiana, from where he was finally retired.

Yet one nostalgic baseball moment remained: on July 4, 1996, Indianapolis’s iconic Bush Stadium closed after 65 years, and Beard was one of the invited guest speakers at the site where he had for so long entertained the fans.

On January 7, 2011, Ted Beard turns 90 years old. Sadly, according to his wife, he has very little memory of his past. But in 1993, in his SABR oral interview, when asked if he would do anything differently, he replied, “I would keep my eye on the ball more when I’m hittin’. I had good bat control, but as I look back, I would take my eye off the ball just before it got in there. Didn’t know it at the time, but I know it now. So the next time around, I’m going to keep my eye on the ball.”

It sounds like a winning approach.

Last update: October 18, 2021 (zp)

Sources

Ted Beard interview conducted on January 15, 1993, by Rick Bradley for SABR Oral History Committee.

My sincerest appreciation to Mrs. Ted Beard for a telephone interview conducted October 10, 2010, as well as several follow-up emails.

My sincerest appreciation to Hal Keller for a personal interview by phone on October 12, 2010

Ted Beard player file obtained from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY.

Archie Stimmel player file obtained from the National Baseball Hall of fame, Cooperstown, NY.

My sincerest appreciation to SABR members Everett Cope, Andy McCue and Cappy Gagnon for information pertaining to the Helms Athletic Foundation.

United Press International (UPI) via NewpaperArchive.com

Associated Press via (AP) NewpaperArchive.com

International News Service (INS) via NewpaperArchive.com

The Sporting News

New York Times

http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/PONY_League

http://www.baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=beard-001cra

http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Ted_Beard

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/b/beardte01.shtml

www.retrosheet.org

http://web.minorleaguebaseball.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=85

http://frederickymca.org/?page_id=1728&navid=13

http://www.ballparktour.com/Sportsmans_Park.html

[1] The ten players who homered over the roof were Ruth, Beard, Mickey Mantle, Wally Moon, Bob Skinner (2); Eddie Matthews (2): Jerry Lynch; Rusty Staub; Willie McCovey (2); and Willie Stargell (7).

[2] In addition to the Maryland State League, another Frederick County rural baseball circuit was the Tri-County League. In a phone interview with Hal Keller, Charlie’s brother, who also grew up in Middletown, Hal denied having ever met Ted Beard, though he knew of him. However, Hal’s brother, Hugh, played in the Tri-County League (Hal was batboy for Hugh’s team), and it’s likely Hugh and Beard played against each other.

[3] After his outstanding 1946 season at Class B York, Beard inexplicably went to 1947 training camp with the Minneapolis Millers in Leesburg, Florida. There, he collected six hits in his first eight ABs, including a 363-foot homer. He then began the 1947 regular season at Class A Albany. However, after a slow start, during which he batted .143 in 10 games, he was returned to York.

[4] Number 85 of the top 100 as compiled by minor league historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright.

[5] Beard finished second to Kansas City’s Al Rosen as the American Association Rookie of the Year and was also voted the Indians’ ‘Most Popular Player’.

[6] By the spring of 1950, Beard had already earned a reputation as a ‘Slingshot Arm.” That spring, in an exhibition game against the Giants, Bobby Thomson was on first when Don Mueller singled to right on a hit-and-run. Off with the pitch, Thomson, who had blazing speed, churned full-speed around second. Suddenly he heard Leo Durocher, coaching at third, yell, Stop! Go back! Don’t run on THAT guy’s arm. After retreating to second base, Thomson looked quizzically at Durocher, who just smiled and shook his head; Beard had just rifled the throw to third base. After looking at Beard in rightfield, Thomson saw Pirates’ second baseman Danny Murtaugh pointing to his left arm with his right. Danny was telling him about ‘The Arm.’

[7] The official name is the Alvin G. Quinn Frederick County Sports Hall of Fame. Quinn was the first director of the Frederick County YMCA, which sponsors the Hall. The YMCA, however, doesn’t have room to house the large exhibit, so the Hall currently resides at the Recreation Department. In the future, the YMCA hopes to gain enough space to house the exhibit there.

Full Name

Cramer Theodore Beard

Born

January 7, 1921 at Woodsboro, MD (USA)

Died

December 30, 2011 at Fishers, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.