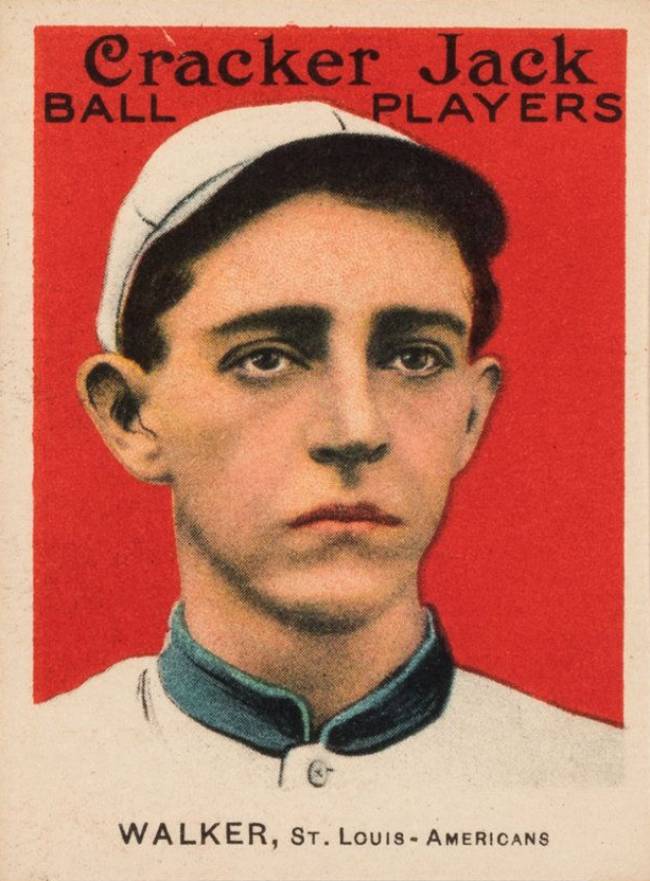

Tillie Walker

A powerful right-handed hitter with a legendary throwing arm, Tillie Walker spent the second decade of the Deadball Era shuffling around the American League, playing for four different teams in the span of eight seasons. After spending time with Washington, St. Louis and Boston, Walker finally came into his own with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1918, when he tied Babe Ruth for the American League lead in home runs. Though Ruth monopolized the home run laurels for the rest of Walker’s career, the red-haired Tennessean still ranked in the top five in the league every year from 1919 to 1922, when he belted a career-best 37 round-trippers.

A powerful right-handed hitter with a legendary throwing arm, Tillie Walker spent the second decade of the Deadball Era shuffling around the American League, playing for four different teams in the span of eight seasons. After spending time with Washington, St. Louis and Boston, Walker finally came into his own with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1918, when he tied Babe Ruth for the American League lead in home runs. Though Ruth monopolized the home run laurels for the rest of Walker’s career, the red-haired Tennessean still ranked in the top five in the league every year from 1919 to 1922, when he belted a career-best 37 round-trippers.

During his playing career, Tillie Walker was listed as having been born in Denver, Colorado in 1890. Both the time and place were wildly inaccurate: Clarence William Walker was actually born on September 4, 1887 in Telford, a backwoods town in northeastern Tennessee, not far from where David Crockett grew up. Clarence was the second of three surviving children (four others died in infancy) of Nelson and Florence Desler Walker. When Clarence was still a young child, the family moved a few miles west to the tiny hamlet of Limestone, where Nelson supported his family by constructing wagons and carriages. According to legend, as a boy Clarence strengthened his arm by throwing rocks into the Tennessee River, though that was located many miles to the west.

After finishing high school, Walker spent a few years working as a telegraph operator. In 1908, he played for the Washington College (Tennessee) baseball team, and the following year spent time with the University of Tennessee squad. That experience earned him a contract with the Spartanburg Spartans of the Class D Carolina Association in 1910. In 108 games, Walker batted just .242 while playing the outfield. The following year was a different story, however, as Walker began the season with a .390 batting average through his first 35 games. On June 2, the Washington Senators purchased his contract for $2,250.

Listed at 5’11” and 180 pounds, the right-handed Walker spent the rest of the 1911 campaign as Washington’s regular left fielder, and finished the season with a respectable .278 batting average, though he collected just 12 extra base hits (two of them home runs) in 356 at-bats. From the start of his major league career Walker dazzled observers with his powerful throwing arm. He collected 14 assists in 94 games, though he also committed 16 errors. Walker’s defense became even more problematic in 1912, when he committed eight errors in 34 games in the field for a ghastly .837 fielding percentage. It was a performance bad enough to earn him a spot on the bench, despite a solid .273 batting average. On August 25, Washington released Walker to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association, where he spent the final month of the season.

Once again, Walker’s bat earned him a promotion back to the big leagues, as he batted .307 with 89 runs scored in 131 games for the Blues in 1913. On August 24, one year to the day after he had been sent down, the St. Louis Browns acquired Walker from Kansas City for first baseman Bunny Brief, outfielder Pete Compton, pitcher Mack Allison, and more than $15,000 cash. In 23 games for the Browns, Walker batted .294, earning himself a spot on the St. Louis roster for 1914.

Established as the club’s everyday left fielder, Walker, now often called “Tillie” (though the precise origin of this nickname is not known), enjoyed his first standout season in 1914, batting .298 with six home runs (tied for third best in the league), 24 doubles (tied for sixth), 16 triples (fourth best in the league), and a .441 slugging percentage (eighth best in the circuit). Walker was also a patient hitter: his .365 on-base percentage, fueled in part by 51 walks, led the Browns, and his 72 strikeouts were the fourth most in the American League.

But Walker distinguished himself even more with his throwing arm, as he racked up a league-leading 30 assists. According to The Sporting News, Walker’s throwing arm was “the talk of the American League circuit.” However, some observers felt that Walker’s arm, while powerful, was also too wild. In 1923, The Sporting News observed that Walker “was famous for his throwing arm, but his throws were not always made with judgment, nor were they always well aimed.” Errant throws may be the reason that Walker led the league in errors three times during his career. Nonetheless, thanks in large part to Walker’s hitting and defense, the Browns finished in fifth place in 1914, their best showing since 1908.

In 1915 the Browns slid back to sixth, and Walker regressed with the rest of the team, as his batting average fell by 29 points to .269, his on-base percentage slid 42 points to .323, and his slugging percentage dipped 76 points from his 1914 total, to .365. Playing primarily center field for the first time in his major league career, Walker led the league in outfield assists with 27, but also paced the circuit with 23 errors.

More troubling, Walker fell out of favor with some of his teammates, and the following spring the Browns’ new manager, Fielder Jones, sold him to the defending champion Boston Red Sox for $3,500. The sale puzzled many observers of the game, who, according to one newspaper account, “wanted to know why a man good enough for [the] world’s champions was not good enough for St. Louis.” The trouble was Walker’s temperament. “He is said to be quite a hitter when he feels like hitting, but grouches and sulks when he does not whang a double or a triple every few minutes. In other words, he worries more about his batting average than about the club’s record of games won. Fielder Jones could not stand for that a minute. Jones is a baseball theorist and teamwork exponent, hence he decided to let Walker go.”

Serving as Tris Speaker‘s replacement in center field, Walker batted .266 for the Red Sox in 1916, with 29 doubles, 11 triples, and three home runs, one of which came at Fenway Park on June 20 against New York Yankees right-hander Ray Keating. The blast, which carried over the park’s 24-foot left field barrier, was the only home run hit by Boston at home all season. (Opposing teams also managed to hit only one home run at the park that year.) At the time, Walker was the only player to have cleared the left field fence more than once, as he had also achieved the feat twice while playing for the Browns.

After batting .273 in Boston’s five game World Series triumph over the Brooklyn Robins, Walker spent one more season in the Hub City, finishing the 1917 campaign with a disappointing .246 average in 106 games. After the season, Walker was shipped to the Philadelphia Athletics, along with catcher Hick Cady and third baseman Larry Gardner, for first baseman Stuffy McInnis. The trade proved to be a steal for Connie Mack‘s ballclub, as Walker took advantage of Shibe Park‘s more accommodating dimensions to become one of the American League’s top longball threats. Playing for the dreadful Athletics, in 1918 Walker batted .295 and tied former teammate Babe Ruth for the major league lead in home runs with 11. The following year, as the Athletics limped to a 36-104 finish, Walker batted .292 and smacked 10 round-trippers, all of them at home. But Walker had slowed perceptibly in the field.

As the curtain closed on the Deadball Era and the home run became more fashionable, Walker kept up with the times. In 1920 he finished third in the American League with 17 home runs, 12 of which came at home. That year he also led the league in assists for the third and final time in his career, with 26. In 1921, Walker smashed 23 home runs, 18 of which came at home, and drove in a career-high 101 runs. With the Athletics having finished dead last every year since 1915, Mack decided to play to his slugger’s strength for the 1922 season, and moved the left field fence in by 46 feet, to a distance of 334 feet. Walker responded by hitting 37 home runs (26 at home) and driving in 99 runs. He also posted a career-high .549 slugging percentage, eighth best in the league.

But as good as Walker was, Philadelphia’s pitching was even worse, as the staff allowed a league-worst 5.35 runs per game and the club finished in seventh place. Early in the 1923 campaign, Mack benched Walker, whose diminished range had also made him a defensive liability. Explaining the move, The Sporting News reported that “in the eyes of Mack…the day of slugging homers is passing and…baseball is returning to normalcy. Mack figures good fast fielding of fly balls is of more value in winning ball games than smashing out homers now and then, so Walker, who has lost his speed and cunning as a fielder, goes to the bench.” Appearing in only 52 games for the Athletics, Walker finished the 1923 season with a productive .275 batting average and .368 on-base percentage. Nonetheless, the 36-year-old drew his release in December.

Walker spent the next several seasons bouncing around the minor leagues, playing for Minneapolis in the American Association, Baltimore and Toronto in the International League and Greenville of the South Atlantic League. He later served as an umpire in the Appalachian League for two seasons, and managed that league’s Erwin, Tennessee club — about 10 miles away from his hometown — for part of the 1940 season.

After his baseball career ended, Walker lived full-time in Tennessee. His 1921 marriage to Fanella Pomeroy, which produced two children, ended in divorce. In his later years, Walker worked as a highway patrolman. He died suddenly in Unicoi, Tennessee on September 21, 1959, at the age of 72, after suffering a heart attack in his brother’s home. He was buried in Urbana Cemetery in his hometown of Limestone.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Clarence William Walker

Born

September 4, 1887 at Telford, TN (USA)

Died

September 21, 1959 at Unicoi, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.