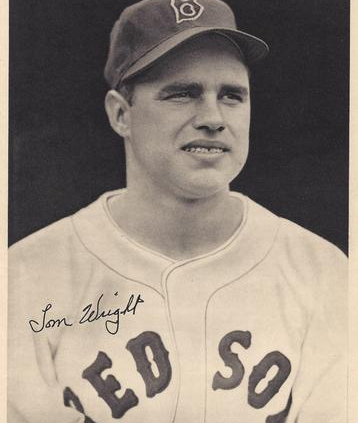

Tom Wright

Tom Wright, a left-handed hitting outfielder who played major league baseball over nine seasons, still lived in 2007 in the town where he was born: Shelby, North Carolina. Wright was born on September 22, 1923, one of 10 children (five boys and five girls) raised on the family farm run by his father, J.B. Wright. “Cotton is the thing that sold, but with our family and everything and as poor as we were, they grew all kind of vegetables and everything else,” he said recently.

Tom Wright, a left-handed hitting outfielder who played major league baseball over nine seasons, still lived in 2007 in the town where he was born: Shelby, North Carolina. Wright was born on September 22, 1923, one of 10 children (five boys and five girls) raised on the family farm run by his father, J.B. Wright. “Cotton is the thing that sold, but with our family and everything and as poor as we were, they grew all kind of vegetables and everything else,” he said recently.

Like many families during the Depression, the family faced tough times, but Tom says, “If I look back, it was real rough. They didn’t know it, because we grew a lot of our own food. The textile mills didn’t pay anything but we had jobs. Back then, you had your company stores and all that stuff. You could go get your food and then pay for it when you got paid. It was just like that week to week was the way we lived. I never went hungry, though I did eat a lot of beans and a lot of bread. And taters and stuff like that, that we grew ourselves. We didn’t consider us all that poor, although we were dirt poor.”

With 10 children in the family, they had enough for a baseball team, but none of his siblings showed much interest in baseball. The local textile mill had a team and Tom’s brothers played some growing up, but never amounted to much. The family house was down the street from the mill’s ball field, just about a block away, Tom and some of the kids his own age played endlessly on the field. “That’s where I was raised, really — on that ball field. When we were kids, we ate, we went to the ball field. We went back. A lot of times, it wasn’t until close to dark before we’d ever go back home. Just playing, in summertime when we were out of school.”

Tom who grew to 5 feet 11, played high school ball for Shelby High and some American Legion ball, and even some semipro ball in Florence, South Carolina, during the summer of 1941. Tom typically played infield, mostly shortstop, but after he reported to Danville-Schoolfield in the Bi-State League for the 1942 season, he was converted to outfield. “They had infielders and they said, ‘You swing like an outfielder’ — so I went to the outfield.” He even pitched a bit for Danville, though his one start didn’t end too well. “I had a good arm. I went in and relieved two or three times, and I got them out. Then they pitched me one ball game. George Ferrell (brother of Wes and Rick, both major league stars in the 1930s) was the manager of Rocky Mount. I done good all day long, beating them, and I let a little curveball slip and get over the base. They had a short left field. He hit it out. He’s the one that beat me.”

Red Sox scout Eddie Montague signed Wright to the Red Sox in 1941, right out of high school. He’d watched Wright play both high school and American Legion ball and inked a contract before graduating. It didn’t cost the Red Sox a penny. “I guess I didn’t have enough sense to ask for a bonus,” Wright told writer Tommy Fitzgerald of The Sporting News (August 24, 1949). “I was just so tickled to get a chance to play professional baseball that it didn’t make any difference.”

The Red Sox asked him to report to Canton, Ohio, but he was too young and didn’t want to travel so far from home so they suggested Florence. Come 1942, he was assigned to Danville and batted .241 in 394 at-bats, driving in 60 runs. After the season, he was picked up by Greensboro under their working agreement with Danville, but World War II intervened.

He had registered for the draft and was finally taken in March 1943, missing the next three seasons. After the war, he wrapped up his high school diploma, getting a lot credit for the life experiences he’d had. Under The GI Bill, he attended Howard Business College, too, until the money ran out. The owner of the college allowed Tom to keep on at his own pace, though, without payment, and he finally finished up that degree, too. That was mixed in with selling automobiles, painting, some carpentry, and work in supply rooms — a little bit of everything, ”so I’d have something I could do when I got through with baseball.”

Tom served in the Army Air Corps. He trained as an aerial gunner and an armorer, in charge of the weapons. He tore up a foot parachuting during training in Wyoming, and by the time that healed up, he’d already heard from a friend who had put in his missions overseas. His friend urged him to get out of active flight and transfer to ground crew work. He did, giving up his sergeant’s stripes and going overseas as a private first class. The 13th Air Force sent him to the South Pacific, assigned to a P-38 outfit. “I looked after loading bombs and looked after the guns. I went up through New Guinea, and then a replacement center and then up through Moreton, Biak, and those islands over there and I wound up on Palawan in the Philippines. They tell me that’s a resort place now. There wasn’t nothing over there at that time. I was in for three years, and I spent a year overseas. I was a corporal. I was up for sergeant, they said, but I wasn’t worried about that. I was worrying about getting home.”

After the war, he took spring training with the 1946 Red Sox in South Carolina. “I’d just got back home from the war. Rainy, misty, cold, and I was trying to throw with some little boy they had training in Florida, but the next day I couldn’t. I hurt my arm. In most of my professional years, I had an arm that bothered me but I tried not to show it no more than I had to.” As it happens, Wright’s foot hadn’t healed perfectly, either. “It’s still got all the fractured bones and all that kind of cracks and everything in it, but it’s OK. I was able to do my whole career with a bad foot. Of course, it was taped up a lot. It was wrapped and taped a lot, but I didn’t complain about it. I was trying to keep a job.”

He was the property of the Scranton club of the Eastern League, and they had so many players coming back from the service and otherwise out for spring training that it was hard for the staff to evaluate what they really had. Wright felt they weren’t really looking at him, so along with one or two others, he simply returned home. In postwar America, the law guaranteed returning veterans the right to return to their own jobs and Wright was reminded that he had a secure job, but he told them he was heading home until they decided where they wanted to send him. They gave him a choice between Canton and Durham. Durham was closer, so he picked that, and played under Pat Patterson for the 1946 Carolina League season. He had an excellent year, leading the league in hitting with a .380 average, banging out an even 200 hits, including 61 extra-base hits, and driving in 116 runs. Nine of those RBIs all came in the July 10 game thanks to two doubles and two triples. His 200 hits remained the league record until 1950. He might have had a few more, except for a time he got beaned that cost him a couple of games. “They were always throwing at me. When you get base hits, they throw at you.”

The next year, he trained with Triple-A Louisville. He had a terrific spring, but ended up the exhibition season suffering painful shin splints from the “sandy Florida diamonds.” (The Sporting News, August 24, 1949) The Colonels were well-enough stocked, so Louisville sent him to Memphis in April but he wound up playing 1947 in New Orleans. Playing for the Pelicans in the Southern Association, he batted .325, again homering 14 times, this time driving in 89 runs, despite missing 11 days after a serious July 29 beaning. After the season, Wright was named to the Southern Association all-star team.

In 1948, he advanced to Louisville and racked up 563 at-bats in 151 games, with a .307 average. His power and RBI numbers were virtually identical to the year before. In September, he got called up to the Boston ball club. He’d only just arrived and got his uniform when manager Joe McCarthy told him, “Wright, get your stick!” It was the top of the ninth inning in a September 15 game against the White Sox. First time up, the first pitch he saw, he hit for a triple to the right-center field fence. He soon scored and when he got back to the dugout, “McCarthy said, ‘Son, you don’t take (pitches) much, do you?’ I guess that’s the only words that man ever said to me when I was with the ball club.” And that included 1949. “He never spoke to the ballplayers. They just sit down on one end and managed. Back in those days, they didn’t have hitting coaches, they didn’t have fielding coaches, they didn’t have all that stuff that they have now. They didn’t coach. They didn’t do nothing.” Players had to pretty much make their own way.

Tom had two at-bats with Boston in 1948 and left with a .500 average. He was with the team right though the end of the year and even had a minor role in the playoff game with Cleveland, entering as a pinch runner for Billy Hitchcock in the ninth. Why did McCarthy decide to pitch Denny Galehouse in the final game? “Everybody there questioned that, because he couldn’t break a pane of glass. He didn’t throw hard. He wasn’t a hard ball thrower. You didn’t slip in Fenway. If you did, somebody’d hit the green wall. That’s what happened to us.”

Wright had been a fan favorite in Louisville and was chosen Most Valuable Players on the Colonels by a vote of the fans. After the season, the Red Sox released Wally Moses to make room for Wright in their plans for 1949. Come springtime, though, it was determined that he needed more seasoning. Wright was candid with Sporting News writer Tommy Fitzgerald that he’d been disappointed in his springtime experience with the Red Sox: “Nobody hardly said a word to me. Nobody showed me anything.”

Fitzgerald classified Wright as a “natural straightaway hitter who sends the ball to all fields” and wrote the Boston’s farm director Johnny Murphy had tried to get him to pull the ball more to right, but the suggestion didn’t work. Murphy also suggested he switch to a larger glove, and that did seem to strengthen his fielding.

In 1949, he spent the full year back in Louisville, again appearing in 151 games, this year rapping out 202 hits and leading the American Association in hitting with a .368 average. Late in the year, he came back to Boston and found himself inserted into the final game of the year. If the Red Sox won the game, they won the pennant and Ellis Kinder had held the Yankees to just one run through eight innings. Unfortunately, New York’s Vic Raschi denied Boston even one run. Sox manager Joe McCarthy called on the AA batting champion to pinch hit for Kinder in the top of the eighth; Wright worked a walk but was retired when Dom DiMaggio grounded into a double play. Kinder was a very good hitting pitcher, and though Wright had gotten himself on base, Kinder’s replacement — Mel Parnell — was hit hard in the bottom of the eighth, and the game was out of reach.

Most of the time that Wright played in the minors, it was center field he patrolled. But in the majors, it was primarily left field, because of his weaker arm. He knew the Red Sox outfield was a hard one to crack, but he made the team in 1950 as a backup. Wright was with the Red Sox for all of 1950, and got most of his playing time in helping out after Ted Williams shattered his elbow during that season’s All-Star Game. Billy Goodman largely took over for Ted in left, and Wright fit in 24 games, 19 in right field and five in left. For the most part, though, he pinch-hit for Boston. He did total 107 at-bats, and hit .318, so he got a fair amount of work.

Manager Steve O’Neill had plenty of praise for his pinch-hitting specialist: “You can call on him any time and he’s just as likely as not to deliver the hit you need. Lots of players lose that split-second timing when they lay off for a while. But Tom can sit on the bench for three weeks, then get up and hit just as well as if he was in there every day.” O’Neill’s comments appeared in a November 1, 1950 Sporting News article; author Steve O’Leary characterized Wright as a “soft-spoken southerner” with a “fine sense of humor and he’s a great guy to have around for morale purposes. That’s another point in his favor with O’Neill, who is blessed with plenty of Irish wit.”

In 1951, he tailed off sharply, and was sent back to Louisville after just 63 at-bats. He was only hitting .222. It was a frustrating time. “Nobody was hitting. Williams wasn’t hitting. There wasn’t nobody hitting. When Cronin (the general manager) called me up and told me I was going back to Louisville, we got in a cuss fight. I told him if he wanted to, just go look up the records of who Williams was hitting against and who I was hitting against, and see who was hitting. We had to separate. I went back out the next day, and I knew there wasn’t no more for me to do but just go back to Louisville. But nobody was hitting. Williams wasn’t hitting, either.” It was indeed an “off year” for Ted Williams; he only hit .318.

After 28 games with the Red Sox, Wright got in 72 games for Louisville, where he hit .282, but he found it “hard to get tuned in,” and after the season was over, he requested a trade. “I told them to get rid of me. They’d done moved me up and down so much. They told me all the time Detroit wanted to buy me and they wouldn’t do it. They’d just keep holding me in Triple-A ball. I told them, just get rid of me. So they sent me to St. Louis.” A late November swap with St. Louis brought Boston Gus Niarhos and Ken Wood and sent Wright and Les Moss to the Browns. In its December 5 issue, The Sporting News contained four separate stories about talked-about trades of Ted Williams, and one suggested that acquiring Ken Wood to play left field was the key element in the trade with St. Louis. Ted was never traded, Wood never panned out, but Wright

opened the 1952 season hitting cleanup for St. Louis.

“Early Wallflower Wright Blossoms as Brownie Daisy,” headlined an early April Sporting News, reporting that Wright had been named starting left fielder. Rogers Hornsby called him “the most improved player on the squad.” Wright had a hot start, but cooled off considerably, striking out quite a lot and found himself playing only infrequently. On June 15, the Browns swapped him and Leo Thomas to the White Sox for Al Zarilla and Willie Miranda. Ironically, it was Zarilla as much as anyone who had blocked Wright from playing more in Boston, and now St. Louis sent him to Chicago to acquire Zarilla. Wright finished the season hitting .258 for the White Sox, up from the .242 he’d hit for St. Louis.

Manager Paul Richards told The Sporting News in August that three of his players, including Wright, would be getting a refresher course in where the strike zone is located come the next spring. “It is my belief that all three of them could be .300 hitters if they laid off the bad pitches,” Richards said of Wright, Jim Rivera, and Hector Rodriguez.

He’s been told, he says, that he led the league in pinch hits in 1953. “I get a little bit of this stuff from fans, saying they’re wanting autographs and this and that and the other. They’ll give me all my records and everything. I’ve never looked them up.” He played in 77 games, getting 132 at-bats and hitting an even .250.

Right at the end of 1954 spring training, the White Sox sent him to the Washington Senators for Kite Thomas. He was on the team all year, but it was a very disappointing one. “I never could get anything going with them. I just couldn’t get my rhythm. I didn’t even feel like part of the team. I never did get going and I was always sorry for that because I wanted to play for Griffith bad.” Wright started the season platooning in right field with Jim Lemon, but he wasn’t the answer to Washington’s problems and wound up largely used as a left-handed pinch hitter. He got 171 at-bats, but it was just too much stop-and-start — and maybe he just wasn’t the same player as he’d been now that he’d hit age 30.

At the end of March 1955, Wright was optioned to Chattanooga and played with the Lookouts for the full year, appearing in 142 games and hitting .293 back in the Southern Association. He drove in 72 runs, and was brought back up to Washington in September, where he had seven at-bats in seven appearances, but didn’t record even one hit. Come the spring of 1956, Wright lacked just under 30 days of major league playing time in order to qualify for the pension, and Senators owner Griffith ensured that he was brought back long enough to qualify. Washington manager Charlie Dressen kept him on the team, but didn’t use him a bit in spring training. “He didn’t even let me pinch hit or do nothing all spring. But I was the first pinch hitter against the Yankees on opening day. Them boys down on the bench said, ’Durn, Tom. What’s he trying to do to you?’ I says, ’I don’t care. Give me the stick.’ I didn’t get a fair run with him, but really I didn’t get a fair run, I didn’t think, because I never did get to stay in the lineup to get my timing and everything. I was just fighting to stay in the major leagues. I wasn’t going to fuss with nobody.” Actually, Wright pinch-ran in the season opener, but pinch-hit in the second game of the regular season, grounding out for the pitcher in the seventh inning. He’d appeared in two games and had just the one at-bat. After he’d logged the requisite time for a pension, Wright was sent to Louisville. Thus ended his time in major league baseball.

When he got to Louisville, Tom recorded a .245 average over 159 at-bats, but was bumped down to Birmingham in midyear. There he did well, hitting .344. He returned again for the 1957 season with Birmingham, but hit only .257. Tom began to figure his time was up. He wasn’t hitting as well, and he didn’t want to travel by air. He asked that he be sent to a club that didn’t fly and was sold to Charleston but he found there was no way to make the schedules without flying, so he just left baseball. Perhaps a bit ironic that the man who’d volunteered to fly in the Army Air Force was now overly anxious at the prospect of travel by air. “I just couldn’t stand it. It made me nervous. I flew good, but those two or three days when you’re waiting before you know you’re going to fly, I was nervous as a cat. It was affecting my life. In fact, I lost my major league contract over it. I couldn’t help it. It was making me so nervous I had to do something.”

He returned to Shelby, and has been there ever since. During the off-seasons, Wright had had a strategy: “I sold automobiles and I painted. I carpentered and I worked in supply rooms and all that kind of stuff. I was trying to do a little of everything so I’d have something I could do when I got through with baseball.” His first job after retiring as a ballplayer was running the credit department for a local clothing company, but he said he “didn’t like messing with other people’s money” and so signed up to make polyester and yarn for Celanese. He worked at their textile plant for just over 21 years, ending up as a supervisor and retiring in 1982.

Tom has one son, who’s retired as well. Tom Wright Jr. played infield for the University of North Carolina and led the team in hits one year. He was offered a chance to go to spring training with Cincinnati, but he’d gotten married as soon as he got out of school and both he and his wife worked as schoolteachers. Tom and his son own a small farm together, raising some cattle and keeping busy.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Source

Interview done by Bill Nowlin. March 6, 2006

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Thomas Everette Wright

Born

September 22, 1923 at Shelby, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.