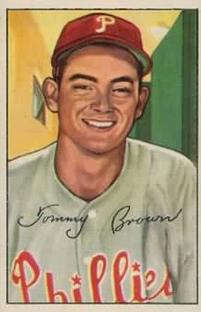

Tommy Brown

Tommy Brown was only nineteen years old and recently discharged from the Army when he joined the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers for spring training in Havana. Playing time would prove difficult to come by for Brown on that Dodgers club with all its players returned from World War II.

Tommy Brown was only nineteen years old and recently discharged from the Army when he joined the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers for spring training in Havana. Playing time would prove difficult to come by for Brown on that Dodgers club with all its players returned from World War II.

But the Dodgers could not send him to the minor leagues under the rules then in force. Because Brown already had two years on a big-league roster, he would have to pass through waivers to be farmed out. The Dodgers were not willing to let Brown go for the waiver price, so he was relegated to end-of-the-bench status.

For the ‘47 season, the youngster appeared in only fifteen games, including six at third base, three in the outfield, and one at shortstop. The right-handed-hitting Brown even suffered the ignominy of starting a game at third base against a left-handed pitcher but, when the Dodgers knocked the southpaw out of the game in the first inning before he had a chance to bat, being replaced by the left-handed-hitting Spider Jorgensen.

Brown had made quite a splash when he was first called up to the Dodgers on August 3, 1944. With Pee Wee Reese still in the military, the Dodgers had tried Bobby Bragan at shortstop, but decided they needed someone more mobile. GM Branch Rickey and manager Leo Durocher remembered Brown from spring training and called him up from the Newport News (Virginia) Builders of the Class B Piedmont League. When Brown arrived in the clubhouse, Durocher told him he was playing shortstop that afternoon in a doubleheader against the Cubs. Brown advised Durocher that he had ridden the train all night, but Leo responded that he didn’t care.

Brown did play the doubleheader, although he was only sixteen years and seven months old. He thus became the youngest position player to appear in a Major League game and the second youngest ever, after Joe Nuxhall, who appeared as a pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds earlier in 1944.

Tommy Brown was a local kid; he was born December 6, 1927, in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. He never knew his father and was raised primarily by an aunt and uncle. He quit school at a young age to work with his uncle unloading barges on the docks of New York. Brown spent his free time playing baseball on the pavement and cobblestone streets and in the famous Brooklyn Parade Grounds. The Dodgers held open tryouts there in 1943 and a friend who played first base on Tommy’s team talked Brown into going with him. They joined about 2,500 other kids and Brown arrived without a glove or spikes, items he did not own. After three days the Dodgers told him and a handful of others that they would hear from the team. Brown was only fifteen years old. Over the winter, the club offered him a chance to attend spring training in Bear Mountain, New York. His “bonus” was the 25-cent fee for the ferry. Brown showed enough promise in spring training to be offered $75 a month to play for the Dodgers’ Class D Pony League farm club in Olean, New York. But Jake Pitler, manager of the Class B Newport News team, claimed him, which meant Brown would earn $125 a month. Tommy was barely sixteen when the season opened, but he proceeded to bat .297 in ninety-one games before his call-up by the Dodgers. He also led the league in triples, with eleven, and socked twenty-one doubles. Brooklyn president Branch Rickey called Brown “the second best prospect in our chain and a veritable Pepper Martin.”

When manager Pitler told Brown he was being called up to Brooklyn, he received a surprising response. Tommy told Pitler that he did not want to go but wanted to finish the year with Newport News because he was hitting well and learning so much. But Pitler said, “No, you’ve got to leave right now.”

Brown faced left-hander Bob Chipman of the Cubs in his debut with the Dodgers. In his first at bat he grounded out, but later, in the seventh inning, slugged a double to left-center. It was in the field, however, that Brown’s nervousness was apparent. He let a routine ground ball by Chipman roll through his legs and in the brief infield practice before each inning in the field, had the fans behind first base scurrying for cover as he unleashed throws that not even six-feet-seven first baseman Howie Schultz could reach. Brown had quickly lived up to his nickname, Buckshot, which Durocher had given him in spring training because of his scatter arm.

In spite of Brown’s shakiness afield and being largely overmatched at the plate, Durocher played him often at shortstop for the rest of the season. Brown finished his rookie campaign with a puny .164 batting average. Still he managed to make contact most of the time, striking out only seventeen times in 160 plate appearances. In the field, he made sixteen errors, mostly on errant throws.

Brown’s boyhood hero was Joe DiMaggio, and early in his career he affected DiMag’s widespread stance. At six feet one and 175 pounds, he even physically resembled DiMaggio. Although no one called Brown a future DiMaggio, Tommy was considered a baseball prodigy because of his youth.

Although Reese was still in the navy in 1945, the Dodgers decided to send Brown to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association for some much-needed seasoning. Tommy again performed well, batting a solid .286 in eighty-five games, with ten home runs. That prompted the Dodgers to recall him in mid-July for the stretch run. Brooklyn was in the pennant race and had decided that Eddie Basinski could not cover enough ground to play shortstop every day. For the last two months of the season, Brown became the regular shortstop and did a commendable job, hitting .245 in 196 at-bats. He clubbed his first big league home run on August 20 against the Pirates’ Preacher Roe in a losing cause.

Tommy was only seventeen years old when he hit that first home run. Five days later, he connected for another circuit blast off Adrian Zabala of the New York Giants. As a result, he is both the youngest and second youngest player ever to homer in a Major League game.

Brown remained plagued by inconsistency in the field, both throwing and catching the ball. He once threw a ball to first base that landed in the upper deck. Another time, a ground ball went right through his legs. Tommy, however, continued as if he had caught the ball and made a phantom throw to first baseman Schultz, who stretched as if he were going to catch the throw. The only problem was that they fooled Dodgers left fielder Augie

Galan, who didn’t see the ball roll by him. The batter circled the bases and Brown was charged with a four-base error.

After the 1945 season Tommy joined fifteen other Major Leaguers on a barnstorming trip to Manila, Tokyo, and stops in the South Pacific to entertain troops by playing against service teams and holding evening bull sessions about baseball.

Major Leaguers returned from military service in droves in 1946, but Brown, now eighteen, was going against the grain. He was drafted into the Army in February after returning from his barnstorming tour. He was discharged in early April 1947 to find Pee Wee Reese holding down shortstop once again and a glut of talent at third base. As a result, Brown played in only fifteen games, mostly in the outfield or as a pinch hitter. He did not appear in the World Series. Manager Durocher was trying to win a pennant and had little time or patience for the development of the raw talent that was Tommy Brown.

Although 1946 and 1947 were pretty much lost years for Brown, he was still only twenty years old and reported to spring training in 1948 with high hopes. Branch Rickey was still enthralled by Brown’s potential and was quoted shortly after the ‘47 season as saying, “Brown is liable to play 154 games for us next year. At what position, we can’t be sure. Maybe third base, maybe the outfield, maybe even first base.”Tommy did receive more playing time in 1948, mostly at third base, but found himself in crusty Burt Shotton’s doghouse. The sixty-three-year-old Shotton had managed the Dodgers in 1947, following Leo Durocher’s one-year suspension. Durocher returned in ’48, but when he left in mid-July to take over as manager of the Giants, Shotton returned. Shotton became unhappy with Brown when Tommy bowed out of a game with what Shotton believed was a minor finger injury. For his part, Brown never knew where he stood with Shotton, even though he played thereafter with illness or injury.

In 1948 Tommy became known as the one o’clock batting champion, a reference to his prodigious hitting in batting practice. For the year Tommy hit 162 batting practice homers in Ebbets Field. He hit only two in fifty-four games and 156 at bats that counted, however. He still had difficulty making solid contact in real competition. Brown batted just .241 for the season. He also had a run-in with his roommate, Carl Furillo. Although the Dodgers hushed up the story, Furillo and Brown got into a fight over an incident in their hotel room. Furillo got much the better of it, and Brown ended up in the hospital.

Although his batting average improved to .303 in 1949, Brown remained a part-time player and pinch hitter, appearing in forty-one games with ninety-five at bats. He made his only World Series appearances in ‘49, batting twice as a pinch hitter. The next season, 1950, was a virtual repeat of 1949. In forty-eight games and ninety-eight plate appearances, Brown had twenty-seven hits, including eight home runs, for a .291 average. He also led the National League with seven pinch hits.Tommy had his biggest day in the big leagues on September 18, 1950, against the Cubs at Ebbets Field. Batting leadoff, he singled off Paul Minner. He then homered off Minner in the third inning. In the fifth, he again smacked a home run, this time against reliever Monk Dubiel. Dubiel was still pitching in the eighth inning when Brown hit his third home run of the afternoon to cap a 4-for-4 day.

Heading into the 1951 season Brown was both a seasoned veteran of the big leagues and a perennial prospect. He was still just twenty-three years old but had six years of Major League experience. New manager Charlie Dressen had high hopes for Tommy and intended for him to play left field. Dressen said he wanted to find a position for Brown because “[i]f that kid can play anything like 150 games, it’s a cinch that he will hit at least thirty-five home runs. You’ve got to love that swing he takes at the ball.”

But once the season began, Brown again had trouble making solid contact. Finally, on June 8, the Dodgers gave up on Tommy’s ever fulfilling his potential and traded him to the Phillies for spare outfielder Dick Whitman and cash. At the time, Brown was hitting just .160 with four hits (and no home runs) in twenty-four at bats. He became a semi-regular with Philadelphia, bouncing between the outfield, second base, and first base. He appeared in seventy-eight games after the trade, hitting only .219, but slugging a promising ten home runs.

Brown was once again lauded as a serious outfield candidate heading into the 1952 season. When camp opened, manager Eddie Sawyer pulled Brown aside and told him that left field was his if he could hit enough to hold it.

Brown could not. He was struggling along with four hits in twenty-nine at bats when the Phillies pulled the plug on June 15, selling him to the Chicago Cubs. Once again, the change of scenery was to Tommy’s liking. He parlayed himself into almost an everyday player, hitting .320 for the Cubs in sixty-one games. The Cubs even played Brown at shortstop for thirty-nine games, a position he had not played for seven years.

Brown began 1953 as the frontrunner for the Cubs’ shortstop position, but he could not keep up his excellent stick work of 1952. He languished below .200 for most of the year and watched as Roy Smalley and Eddie Miksis shared the shortstop position. Brown was again a part-time player, and though his baseball career was far from over, he had played his last Major League game at the age of twenty-five.Tommy landed with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League for 1954, holding down third base while batting .263 in 152 games. He began the 1955 season with the Angels but after twenty-four games he was sold to the Nashville Vols in the Southern Association. There he took over third base and hit a solid .299.

At Nashville in 1956, Brown received some national publicity when against the Pelicans in New Orleans he went 4-for-4, 3-for-3, and 3-for-3 in a three-game series. He also had six walks in the series, thus reaching base in sixteen consecutive at-bats. When the club returned home to Nashville, Brown walked four straight times, meaning that he had reached base twenty times in a row.

He was voted to the Southern Association All-Star team but, more importantly, was purchased by the Cincinnati Reds on July 15. However when he arrived on the train from Nashville, Tommy couldn’t lift his right arm above his shoulder. He had apparently landed on the shoulder a couple of weeks earlier when diving for a ball against the Atlanta Crackers. As a result the Reds quickly sent him back to the Southern Association. Brown finished the year in Nashville, batting an impressive .316 with ten home runs and eighty-five runs batted in. His stellar year earned him an invitation to the 1957 Chicago White Sox spring training in Tampa, Florida. But when the season began, he was back playing third base in Nashville, where he slumped to .256 in 139 games.

He returned to Nashville for the 1958 season, before shifting to the Chattanooga Lookouts in the same league after the Washington Senators organization acquired him. For the year, he hit .266 with eight home runs. He split 1959 between Chattanooga and New Orleans, batting .259. Although he was only thirty-one, Brown was tired of life in the minor leagues and retired after that season.

Brown had married a woman from Nashville and so stayed in the area after his playing career, working at the Ford Glass Plant for thirty-five years, before retiring in 1993.

He died at the age of 97 on January 15, 2025, in Altamonte Springs, Florida.

Sources

Roberts, Robin and C. Paul Rogers III. The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996.

Traughber, Bill. “Tommy Brown Recalls His Career,” SABRgraphs, September 24, 2009.

Tommy Brown clippings file, Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Thomas Michael Brown

Born

December 6, 1927 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

January 15, 2025 at Altamonte Springs, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.