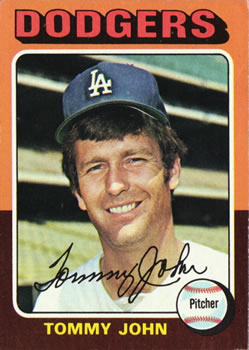

Tommy John

The remarkable longevity of Thomas Edward John’s career is surprising considering the left-hander’s actual performance as a pitcher. While Tommy John was a solid pitcher with a good curve and a sinking fastball, he did not possess the overpowering stuff of near-contemporaries like Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, or Steve Carlton, nor did he have the guile of Gaylord Perry, Don Sutton, or Phil Niekro. John never inspired fear in the teams he opposed, yet somehow he pitched and won games (nearly 300 of them, in fact) well into his 40s. In fact, John’s 26-year career is second in duration only to Nolan Ryan and Cap Anson’s 27.

The remarkable longevity of Thomas Edward John’s career is surprising considering the left-hander’s actual performance as a pitcher. While Tommy John was a solid pitcher with a good curve and a sinking fastball, he did not possess the overpowering stuff of near-contemporaries like Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, or Steve Carlton, nor did he have the guile of Gaylord Perry, Don Sutton, or Phil Niekro. John never inspired fear in the teams he opposed, yet somehow he pitched and won games (nearly 300 of them, in fact) well into his 40s. In fact, John’s 26-year career is second in duration only to Nolan Ryan and Cap Anson’s 27.

Despite many career ups and downs, and though he rarely had his team managers’ and owners’ full and complete confidence, Tommy John possessed something crucial to sustaining his career. Call it heart, moxie, perseverance, or just plain guts: Whatever you call it, John had enough of it to get through sore arms and injuries, past bad contracts and contentious relations with management, and through two critical turning points that would have ruined just about any other player—no matter how gutsy. Indeed, how Tommy John responded in general to the inevitable twists and turns of a major-league career reveals a man who deserves consideration for election to the Hall of Fame.

The second of John’s major crises came on August 13, 1981. On that day, his third child, a son named Travis who was then just 2 years old, fell from a third-story window and struck his head on the fender of a parked car. Tommy was in Detroit with his team at the time, the New York Yankees, when he got a frantic call from his wife, Sally. John immediately flew to New Jersey to be with the family, and, for 19 days while Travis lay in a coma, he stayed by his child’s side, pitching home games when it was his turn but remaining home when the team traveled for away games. “As far as I was concerned,” John later said, “there was never any choice. How can you choose baseball—or any job, or any profession—ahead of your little boy? … Could I ever sleep at night with the thought that I had shirked the job of bringing my son back to full health and strength?”1 No one in baseball outwardly questioned John’s decision. Still, it was a relatively unprecedented act by someone who was being paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to throw a baseball, especially for a playoff-bound team owned by the occasionally ruthless George Steinbrenner.

Tommy John’s decision was the right one. Travis eventually recovered from his injuries and resumed a normal life, even throwing out the first pitch in a Yankees playoff game against the Milwaukee Brewers. But John had long exhibited, over his long career, an ability to sense exactly the right thing to do to overcome hard obstacles. As a player coming up, John had proved himself over and over against prevailing conventional wisdom and misjudgment. When he was signed by the Cleveland Indians out of Gerstmeyer High School in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1961, he was a tall, rangy kid already tagged a “finesse pitcher,” as well as a high-school basketball star who was being heavily recruited to play at several major colleges, including Adolph Rupp’s legendary University of Kentucky team. The initial baseball scouting report on John suggested that his curveball was, even at the age of 18, a major-league pitch, but that he would have to develop a fastball.

John had learned to throw the curve from a friend of his father’s in Terre Haute, Arley Andrews, who had been a minor-league pitcher in the Philadelphia Phillies system. Tommy relied on the pitch so much that he had once had to go against his high-school coach’s express order not to throw the pitch during a game against his high school’s chief rival, Danville High. “Those scouts don’t come here to see you throw curves,” the coach told the young pitcher. “They want guys that throw hard.” To which John responded, with all the cockiness of a high-school star who had lost only one game to that point in his high-school career (by graduation he was 28-2): “The heck with that idea. I’m going to keep right on throwing that curve the way Arley showed me.”2

John lost the game but was satisifed that he played the game he wanted to play. Still, the scouting report written that day by the Indians’ scout, John Schulte, and the resulting label of John as a pitcher with less than overpowering speed, stuck with him for years afterward. And although John struck out plenty of hitters over his career—he was right at or slightly above the league average for strikeouts per nine innings through most of his career—he himself admitted later that he came to believe the label. The truth was that John’s fastball was not particularly fast. It was generally clocked—using the radar guns that came into use when John was in his 30s—at around 85–87 mph. But that didn’t mean John had a poor fastball; after all, speed is only one factor that makes a good fastball. Early on Tommy John learned that if he was going to survive long as a major leaguer he would have to do something to gain an edge against the batters.

In 1961, the year that John signed with the Cleveland Indians, the 18-year-old was sent to the team’s farm club in Dubuque, Iowa, of the Class D Midwest League. Here, in a league made up mostly of rookies, John pitched well, winning ten games and losing only four, and he earned a promotion for the next season to Charleston of the Class A Eastern League, where the level of competition moved up a notch. John now faced much more adept hitting, and in this competitive atmosphere, he suddenly learned something about himself: He simply did not know how to pitch. “I was rearing back on every pitch and firing with all my strength at the strike zone,” he later said of that year. “As a result I kept getting behind in the ball-and-strike count, often running it to three balls and no strikes, so I just had to put my fastball right over the plate and get it creamed.”3 John not only got shelled on numerous occasions, but under the pressure of the constant poor ball-strike counts he began to walk tons of batters.

The man who came to his rescue in 1962 was, according to John, Steve Jankowski, a player-coach in the Indians’ system. “He simply reminded me that I was not the only man on the team, that there were eight others in the field to help me put batters out,” Tommy said. Jankowski told John that, since he could trust his defense to make plays, he didn’t have to throw his hardest on every pitch. “Use about eighty percent of your power and save some for the later innings.”4 The formula worked for John—his control returned and he got more batters out; he was quickly learning how to pitch.

In July 1962, the Indians suddenly promoted Tommy John to their Triple-A Jacksonville team. John, who, at just 19 years old, had a mediocre 6-8 record at Class A, felt more than a little out of place. Many of the players he played with and against were seasoned players, five, six, even ten years older. Fortunately for him, a team coach, Al Jones, took John under his wing. Among other things, Jones directed him to pitch whatever his catcher told him to pitch. As a result, John pitched fairly well, recording two wins against two losses over the last part of the season and two wins in the International League playoffs.

John did not have as easy a time in 1963, at least not at first. Jones had left the team, and Tommy struggled in Jacksonville until he was sent back to Charleston for more seasoning. Here he performed so well—going 9-2 with a 1.61 ERA—that he earned a late-season call-up to the majors. With the big-league squad, John appeared in six games, and earned the admiration of Indians manager Birdie Tebbetts by giving up only five earned runs in 20 innings. Tebbetts called John’s fastball “deceptive,” which may have been a way to say it didn’t have the velocity he expected, or it may have been admiration for its sharp, natural sinking movement.

Before the start of 1964, expectations were high for the 21-year-old John, and for the Indians, who had finished in the middle of the American League in the previous four seasons. With a stable of young and promising arms—including Luis Tiant (age 23), Jack Kralick (29), Sonny Siebert (27), Sam McDowell (21), and now Tommy John—added to a pitching staff that had in 1963 broken the American League record for strikeouts (with 1,018), the team’s management hoped it was building a squad that could become a perennial winner. “I believe,” Birdie Tebbetts wrote in a sports column even before spring training had begun, “the Cleveland Indians have rounded the corner in their quest for a contending position in the American League pennant race.”5 But neither John nor the Indians fulfilled their promise in 1964. With Tebbetts starting the season sick in bed, Cleveland coaches could not resist the temptation to tinker with John’s approach to pitching. The team’s pitching coach, future Hall of Famer Early Wynn, told John he should learn to throw a slider. At first the young left-hander obliged, but the changes John made to his delivery to accommodate the new pitch affected his control. The Indians finished sixth, and John, who went 2-9, was demoted to Triple-A Portland (Pacific Coast League).

John returned to his usual two-pitch routine at Portland, slowly becoming effective again, but during the offseason the Indians decided to cut their losses on the young pitcher. On January 20, 1965, John was part of a three-team trade that brought Rocky Colavito and Cam Carreon to the Indians and sent John, outfielder Tommy Agee, and catcher John Romano to Chicago.

With the White Sox, John became a regular starter for a solid team that finished second in the American League for the third straight year, and he showed improvement in each of his next four seasons. In 1968 he pitched well enough to be chosen for the American League All-Star squad, but in August of that year he injured his shoulder in a fight (Detroit’s Dick McAuliffe charged the mound because he believed John had thrown at his head) and sat out the rest of the year.

With the White Sox, John became a regular starter for a solid team that finished second in the American League for the third straight year, and he showed improvement in each of his next four seasons. In 1968 he pitched well enough to be chosen for the American League All-Star squad, but in August of that year he injured his shoulder in a fight (Detroit’s Dick McAuliffe charged the mound because he believed John had thrown at his head) and sat out the rest of the year.

While John was able to return in 1969, he seemed less effective, and over the next three seasons the White Sox management lost confidence in his pitching, even as the team slid in the standings. John had particular trouble working with Johnny Sain, the Chicago pitching coach toward the end of John’s White Sox tenure, who again seemed bent on toying with John’s pitch selection and mechanics. After the White Sox set a franchise record by losing 106 games in 1970, John had his worst full season in 1971. He went 13-16 with a 3.61 ERA, and the team traded him to the Los Angeles Dodgers for slugger Dick Allen in the following off-season.

With the Dodgers, Tommy John’s fortunes changed. Up to this point in his career, his won-lost record was only 84–91, and he was seen as a middle-of-the-rotation starter at best. But on the Dodgers this would change. Part of the improvement was finally gaining acceptance for the pitcher that he was, instead of the one a coach or manager thought he could be. John gave full credit to Dodgers pitching coach Red Adams for this. “When I joined the club,” he wrote, “I was still convinced that I had only a mediocre fastball and that I was going to have to depend chiefly on my breaking pitches to win ball games. But Red disagreed with me, emphatically.” Adams told John that he had a good fastball, that while it was not going to set any speed records it had a lot of movement. “You’ll get plenty of batters out with that.”6

In 1972 John won 11 (against 5 losses)—the only hiccup occurring in a game against the San Francisco Giants on September 23. While attempting to score from second base on a base hit to right field, he slid hard and jammed his pitching elbow in the ground. The blow jarred loose some bone chips in his elbow, inflaming the joint enough to close down his season. (During the offseason, the elbow was cleaned up by the team surgeon, Dr. Frank Jobe, a figure who would become critically important to John and, indeed, to all of baseball just two seasons later.)

In 1973 John returned stronger than ever and won 16 games. And in 1974 he was on pace to have his best season. But this was when he met the first of his major life obstacles—one so great that no one expected him to overcome it. No pitcher had ever faced what John now faced and kept his career alive. John himself compared it to a dead-end prison sentence. Yet once again, despite the hopelessness, it was simply not in John’s nature to let himself quit.

The crisis occurred on July 17, 1974, during a twilight game at home against the Montreal Expos. John, a veteran now at 31, was arguably the best pitcher on a good Dodgers team, which was fighting to reach the postseason for the first time since 1966, the legendary Sandy Koufax’s last year with the team. Just before the All-Star break, John was leading the league in victories, with 13, and had an ERA of just 2.59. But on this day John was, as was widely reported in the media at the time, and as he admitted later, annoyed. This was because he had not been chosen by All-Star Game manager Yogi Berra for the National League’s pitching staff. This omission, which Berra always claimed was not his doing—John’s spot was supposedly filled by Steve Rogers of the Montreal Expos due to a rule requiring each team to have at least one representative—later became the source of a nasty rumor that continued to linger over John, despite his denials.

Working in the third inning with a 4-0 lead over the Expos, John was pitching to Hal Breeden with nobody out and runners on first and second base. John was not worried. Breeden was a dead pull hitter, and John knew that if he could entice him to swing at a sharp sinker on the outside corner it was likely he would hit into an inning-crushing double play. With one ball and one strike on the batter, John released what he hoped would be a rally-killing pitch. That was when everything went wrong.

Later, John said that nothing seemed unusual about his windup or delivery, though he conceded, as a sportswriter later wrote, that his body may have been “too far ahead of his arm at the critical moment when the ball is released.”7 Whatever the reason, after the throw John felt what he called the “strangest sensation I had ever known.”8 John’s arm went suddenly dead. “Right at the point where I put force on the pitch, the point where my arm is back and bent, something happened,” he explained. “It felt as if I had left my arm someplace else. It was as if my body continued to go forward and my left arm had just flown out to right field, independent of the rest of me.”9

John’s left arm did not experience pain so much as a strange sort of absence and the sound of a “pop” from inside the arm. The ball, meanwhile, “blooped” to the plate, coming in well out of the strike zone. John got the ball back from his catcher, wondering what was going on. He tested his arm, and it felt fine, moving freely without pain. So he set himself again, checked his runners, and delivered another sinker. And the same thing happened: dead arm, bloop pitch, but this time with a “thump” sound (or feeling) in his forearm, as if two hard objects were bumping into each other. John still felt no pain, but he also knew he could no longer pitch. “You’d better get somebody in there,” he told his manager, Walt Alston, when he came to the mound. “I’ve hurt my arm.” The Dodgers went on to lose the game, 5-4, and John went to the trainer’s room with little idea of what lay in store for him.

It took some time for the seriousness of John’s injury to become clear. Like many pitchers, John had had trouble with his arm and shoulder before, and he had recovered from it. Besides the bone chip surgery in 1972, he had separated his shoulder in 1968 in the fight with McAuliffe.

Perhaps because John had recovered easily from these earlier injuries, the idea that this injury was more serious, more momentous, took a long time to settle in his mind. In the immediate aftermath of that July night in 1974, Dr. Jobe took John into a back room at Dodger Stadium and examined his arm but was unable to determine what exactly was wrong. He advised John to ice the arm and give it a few days’ rest; and John, who had resisted having surgery on his shoulder in 1968, preferring to let the ligaments heal on their own, took Jobe’s advice.

It was while John was waiting for signs of recovery to his arm that the rumors began to spread. Stories had appeared in the media before his start against Montreal about John’s frustration with Yogi Berra. Now, after the injury, stories circulated that the cause of the injury—the reason that John had strained his arm —was that the pitcher had been trying to prove Yogi Berra wrong by throwing too hard. “That was a really ignorant statement,” John later said. “No one who really knows me could have dreamed up that tale. … Any experienced pitcher knows that you have to pitch within your own capabilities and that overmatching is just a quick route to the showers.”10 Dr. Jobe agreed with John on this. An injury like John’s in 1974, he said, was a result of long-term stress on the arm. “We call it the Overuse Syndrome,” Jobe said. “If a person throws very hard for a long period of time, the body responds with an inflammatory reaction. This can cause a scar, calcification, degeneration, and rupture of the ligaments. [And] the difference between throwing a ball hard enough to get a major-league hitter out and hurting the arm is infinitesimal.” Jobe knew whereof he spoke. He had started working for the Dodgers in 1964, the same year that Sandy Koufax began to develop his own elbow trouble. And he had been with the team in 1966 to see Koufax finally succumb to the devastating pain.

After a few days, John’s elbow had not improved. If anything, it felt worse, with spasms tightening the muscles on either side of the joint even as the range of motion of the forearm was oddly wide. Jobe took x-rays of the pitcher’s arm, but he couldn’t decide how extensive the ligament damage was. He sent John to a specialist, Dr. Herb Stark, who advised a treatment of “rest and home therapy,” even as the Dodgers’ fight to get to the postseason neared the stretch run and the team was anxious for good news about one of its top pitchers.

In mid-August, after resting his arm for a month, John joined the Dodgers in New York and atempted to throw batting practice. He was unable to reach the plate, and he again felt “nothing” in his arm. Desperate, he asked Dodgers trainer Bill Buhler to tape his elbow up snugly, as he might do when a player had twisted his ankle. The support helped. John was able to feel his arm enough to control where the ball went, but at the same time his pitches had nowhere near their normal velocity or movement. The pitcher then went to manager Alston and told him the news—that it appeared his arm was done for the season. John then called Dr. Jobe and told him what had happened. He also told the doctor that he had made a decision that would forever change his life, his career, and indeed, the sport. He told Dr. Jobe he wanted him to operate.

Dr. Jobe had talked with John about his idea for an operation during the previous month. It was a surgery that Jobe had imagined years earlier, but back then, Jobe said, “you didn’t see many major-league pitchers with scars on their arms.”11 Prior to the medical advancements in the 1970s, when athletes began to treat their ailing knees and elbows with new arthroscopic surgical procedures, pitchers with tired or sore arms preferred to treat themselves with palliative medicine, not reconstructive.12 Most players before the 1970s knew that the moment you went “under the knife” your career was likely over. And so countless ballplayers had tried to play through the pain, and countless ballplayers had seen their career ended from lack of proper treatment of their ailments. John himself admitted he was “extremely leery” about undergoing surgery. “At the time,” he said, “operations on arms and shoulders not only weren’t that effective, but were dangerous.”13 But John had come to trust Jobe. And he knew that without the surgery he stood no chance to get back on the mound.

This is where “heart” played a key role in saving Tommy John’s career. Despite the fact that he was entering territory that no ballplayer had ever known, John proclaimed that he would do whatever needed to be done to ensure that he would be able to continue pitching. This was true even if, in the worst-case scenario, John’s left ulnar ligament was completely ruptured and he needed radical transplant surgery. Only someone as willing to stretch his limits as Tommy John could change the longstanding biases of ballplayers against modern medical techniques. This was his real breakthrough contribution to the sport and to his fellow athletes. In fact, the surgery on his elbow was not as groundbreaking a technique as is often depicted. The baseball world hailed the surgery as a first, but Dr. Jobe himself called it a “fairly common orthopedic procedure.” The main technical difference was that the surgery up till then had been usually limited to wrists and hands, not to elbows—as average people don’t often end up with Overuse Syndrome on that body part. Still, this level of surgical repair had never been subjected to the post-surgical rigor that a major-league pitcher would put it through. No baseball player before Tommy John had given himself over to such a surgical procedure while still holding out hope that he could recover and eventually be the player he was before the surgery.

On September 25, 1974, Dr. Jobe, while in the middle of what would become a three-hour procedure, made a fateful determination. “When I went to repair (the ligament),” he said, “because of the long years of wear, there was nothing left to repair. I had to look elsewhere for a substitute.”14 Jobe replaced John’s medial collateral ligament of the elbow, which was completely ruptured, with a new ligament that he harvested from the palmaris longus tendon of John’s right wrist. (Sportswriters later joked that John was the world’s first “right-handed southpaw.”) When John woke up and reached out to learn what had happened during the surgery, he found his left arm—his pitching arm—bandaged and difficult to move. And he found that his right hand was also bandaged.

The recovery from what would become known as Tommy John surgery was more uncertain than the actual procedure itself. “Since no pitcher had ever had this kind of operation,” John wrote much later, “no pitcher had ever come back from it. No one knew what to expect. We were making medical history.”15 The immediate aftermath was the low point. The surgery had damaged the ulnar nerve, and John’s left hand was shriveled into a kind of a useless claw, with feeling in several of his fingers lost. On December 15 Dr. Jobe quietly performed another procedure to reroute the nerve through fatty tissue on the inside of the elbow, well away from the scarring that was affecting John’s hand. This operation was a success; otherwise John would have ended up with a permanent deformity. The next month Dr. Jobe removed the final cast on John’s arm, and the pitcher set to work on restoring the muscle strength and control that he would need to pitch again.

“I worked hard,” he said, “seven days a week, on exercises Dr. Jobe gave me to strengthen the arm. … I worked as hard as I possibly could on my rehabilitation. I never wanted to look back and say: ‘Son of a gun, maybe if I’d worked a little harder in 1975, I might have come back.’ ”16 John attended spring training with the Dodgers in 1975, doing the same work that the other pitchers did, with the exception of throwing the ball. His arm had its full range of motion, but he still lacked full feeling in his fingers and so could not properly grip the ball. Instead, after the daily regimen of exercises and drills ended and pitchers went to throw batting practice, John devised his own practice method: taping his damaged fingers to his working ones so he could grip the ball. “Day after day, for six weeks, I threw against this wall. It took on an almost symbolic aspect, representing the ‘wall’ that I was trying to break through. I’d take four or five balls, throw them against the wall, pick them up again, and continue until I felt tired. … It made for a sorry picture, the once and former major leaguer, tossing feeble bleeders against a concrete wall, looking as polished as a little boy throwing a ball against the steps of his back porch.”17

All through these trials, as he fought to overcome his isolation and the knowledge that no one on the team gave his comeback much of a chance, John said, he repeated one line of Scripture over and over like a mantra: “For with God, nothing shall be impossible.” (Luke 1:37) And he would continue working. The exercises continued after spring training, along with a regimen of hot-and-cold therapy prescribed by Dr. Jobe. John joined the Dodgers in Los Angeles soon after the season began, and he expanded his work to include a “Silly Putty therapy” suggested by trainer Bill Buhler. John combined several eggfuls of the rubbery kids’ toy and kneaded it almost constantly. Later, Dr. Jobe had John squeeze a cut-off golf club. All spring and into midsummer John continued working, running up to six miles, then playing golf each morning, working out with the team and going through therapy with the team trainers in the afternoon.

In June, John was finally rewarded for all of his hard work. One day on the way to the ballpark he had a breakthrough. He suddenly realized that he could uncurl his two paralyzed fingers. In July, during a bullpen throwing session, John felt the power returning to his pitches. He soon was pitching batting practice, impressing the Dodger coaches and teammates so much that he was assigned to the Arizona Instructional League after the season. In his first outing in Arizona, on September 29, he pitched three perfect innings: 39 pitches, four strikeouts, and a bunch of groundballs. He made four more appearances, working his way up to seven innings and continuing to throw well.

John returned to the Dodgers in 1976 and pitched well, starting 31 games, completing 207 innings, and recording 10 wins against 10 losses with a respectable 3.09 ERA. After the season he received the National League Comeback Player of the Year Award, given by The Sporting News, and the Fred Hutchinson Award for Outstanding Character and Courage. His improvement continued in 1977, as he won 20 games against only 7 losses and recorded a 2.78 ERA. That he was a better pitcher now, at age 34 and after radical elbow surgery, was evident not only in his contributing to the Dodgers’ return to the World Series, but also by his second-place finish to Steve Carlton in Cy Young Award balloting.

Over the next three seasons John remained at the top of his game. He won 17 for the Dodgers in 1978, returning with the team to the World Series, where he pitched solidly against the Yankees, though the Dodgers lost the Series. Then, after deciding to test the new free-agent market, John landed with the Yankees and established himself as the most consistent winner for the team with back-to-back 20-win seasons in 1979-80 and second- and fourth-place finishes in Cy Young Award balloting. His record from 1976 to 1981 was 99 wins and 53 losses, a 3.06 ERA, 14 shutouts, 64 complete games, and an average of more than 235 innings per year (after adjusting for the 1981 strike-shortened season).

John hung on with the Yankees for a few more years after this, pitching well during a season (1981) shortened by a players’ strike and by time off to care for his son Travis. In October 1981 the 38-year-old John pitched in the third World Series meeting between the Dodgers and Yankees in five years, though this time he was on the side opposite his old teammates. Again he pitched well, winning one of the three games he started (against no losses) and recording a 0.69 ERA. But it was not enough, and for the third time John was on the losing side in the World Series. Despite pitching for eight more seasons after 1981, John never again appeared in the World Series.

Year after year and well into his 40s, Tommy John’s playing career continued. In 1982 the Yankees traded him to the California Angels, where he struggled without a winning record for parts of four seasons before being released. In 1985 he pitched, not particularly well, for the Oakland Athletics. Released by the A’s after the season but still believing he could pitch, the 42-year-old John secured a tryout in 1986 with his old team, the Yankees. And he proved himself yet again. Over the next two seasons John won 18 games. In 1988 he won nine games for the Yankees, then made the team as a walk-on one last time in 1989—pitching well enough in spring training to be named Opening Day starter—before getting released in May. John finally announced his retirement in September. “I think I could still pitch,” John, then 46, told a reporter in his home state of Indiana, “but it’s a young man’s game.”18

After his playing days, John embarked on a varied career. He worked as a television analyst for the Yankees, Braves, Twins, and for ESPN.com, and he also worked as a coach and in front-office management for several minor-league teams. As of 2011 he lived in Charlotte, North Carolina, with his wife, Sally, did motivational speaking, and wrote a blog19 for Sportable Scoreboards.

As in his playing career, the retired Tommy John still faced his share of challenges. On March 9, 2010, one of his four children, 28-year-old son Taylor, died as the result of a seizure and heart failure because of an overdose of prescription drugs. Less tragically, by 2010 the door had finally closed on another important aspect of John’s life. In 2009, in the last year of his eligibility, John failed to be voted by sportswriters into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Just as during his playing career, John’s contributions to the game seemed misunderstood; His 288 victories made him the winningest eligible post-1900 pitcher not inducted to the Hall. Further, his overall endurance, won-lost percentage (.555, with 288 wins against 231 losses), and ERA of 3.34 were good enough to place him 67th statistically among pitchers—ahead of Hall of Fame pitchers like Red Ruffing, Mickey Welch, Chief Bender, Red Faber, Vic Willis, Waite Hoyt, and Rollie Fingers.

And there’s the little matter of his revolutionizing athletes’ attitudes toward medicine. With 164 of his 288 victories coming after the surgery, John shattered the barrier that said players could not play after undergoing surgery. Since Tommy John underwent ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) reconstruction in 1974, hundreds of top athletes have had their careers saved by what became to be known as Tommy John surgery. If John’s career numbers are not deemed worth of Hall of Fame consideration, then his pioneering gumption, his ability to endure and come back from adversity again and again when no one gave him a chance, does put him among baseball all-time elite. Now that his fate passed to the hands of the Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee, John could only hope that he would be given one last chance for a surprising comeback.

Last revised: May 26, 2021 (zp)

Sources

To prepare this biography, I read hundreds of newspaper articles found using the Newspaper Archive (www.newspaperarchive.com), as well as several Sports Illustrated articles about Tommy John. In addition, I relied on accounts from the following books, particularly John’s two autobiographies:

John, Sally, and Tommy John. The Sally and Tommy John Story: Our Life in Baseball. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983.

John, Tommy, with Dan Valenti. T.J.: My 26 Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam Nonfiction, 1991.

Leavy, Jane. Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy. New York: Harper Perennial, 2002.

Plaschke, Bill. I Live for This: Baseball’s Last True Believer. New York: Mariner Books, 2009.

Notes

1 John, Sally, and Tommy John. The Sally and Tommy John Story: Our Life in Baseball. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983.

2 Ibid. p. 55.

3 Ibid. p. 66.

4 Ibid. p. 66.

5 Florida News Tribune, January 27, 1964.

6 John, Sally, and Tommy John, op. cit., p. 201.

7 Fimrite, Ron. “Stress, Strain and Pain,” Sports Illustrated. August 14, 1978.

8 John, Sally, and Tommy John, op. cit. p. 132.

9 Fimrite, Ron, op. cit.

10 John, Sally, and Tommy John, op. cit., p. 133.

11 Fimrite, Ron, op. cit.

12 Leavy, Jane. Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy. New York: Harper Perennial, 2002, p. 157.

13 John, Tommy, with Dan Valenti. T.J.: My 26 Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam Nonfiction, 1991, p. 129.

14 Fimrite, Ron, op. cit.

15 John, Tommy, with Dan Valenti, op. cit., p. 183.

16 Ibid. p. 184.

17 Ibid. p. 185.

18 Associated Press wire story. Pharos-Tribune, Logansport, Indiana, September 3, 1989.

19 John’s blog was located at: http://www.varsityscoreboards.com/the-bullpen.html

Full Name

Thomas Edward John

Born

May 22, 1943 at Terre Haute, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.