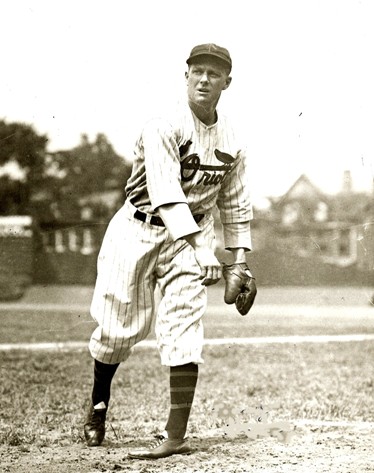

Tommy Thomas

Baltimore native Tommy Thomas signed his first professional baseball contract while still in high school and later became a standout pitcher on one of the greatest minor league teams of all time. The talented tosser went on to flash occasional signs of brilliance during a 12-year stint in the majors. When his pitching career ended, Tommy’s knowledge of our national pastime and his abilty to work with people served him well as a minor league coach, manager and front office executive. The well-respected gentleman ballplayer finished out his days in the game as a successful major league scout.

Baltimore native Tommy Thomas signed his first professional baseball contract while still in high school and later became a standout pitcher on one of the greatest minor league teams of all time. The talented tosser went on to flash occasional signs of brilliance during a 12-year stint in the majors. When his pitching career ended, Tommy’s knowledge of our national pastime and his abilty to work with people served him well as a minor league coach, manager and front office executive. The well-respected gentleman ballplayer finished out his days in the game as a successful major league scout.

Alphonse “Tommy” Thomas Jr. was born on December 23, 1899, in Baltimore. His parents were Alphonse and Anne Thomas. Alphonse’s occupation was listed as a collector in the 1899 City Directory. The Thomas family lived at 823 East Chase Street in Baltimore and had two children, Alphonse Jr. and Annie.

Young Alphonse started going by the nickname of Tommy at an early age. The aspiring athlete loved baseball and learned the fundamentals of the game on the local ball diamonds of east Baltimore. From 1914 through 1918, he pitched for City College (high school). During the summer months he established himself in the local amateur ranks as the ace pitcher for the Maury, Donnelly-Williams Insurance Company baseball team. In 1917, Thomas won ten straight games, helping lead the ballclub to the Baltimore Insurance League pennant.

Thomas broke into professional baseball in May of 1918 while still attending City High School in Baltimore. Herb Armstrong, a talented infielder in his own right, was the baseball coach at City at that time. In the spring of 1918, Herb signed a contract with the International League Buffalo Bisons. The Bisons opened up the season in Baltimore, and Armstrong invited Tommy to try out for the Buffalo team.

The Bisons ended up losing the first two games against the Orioles. Buffalo’s player-manager George Wiltse surprised everyone when he named the Baltimore youngster as his starting pitcher in the third and final tilt of the series. Tommy’s fate with the Buffalo club was riding on the quality of his pitching performance that day.

Thomas took the mound at Oriole Park for his first professional start on May 10, 1918. The 5’10” 172-pound right-hander performed well, defeating Jack Dunn’s Orioles by the score of 5-2 in a rain shortened five-inning affair. Tommy didn’t allow any runs in four of the five frames that he worked. The youngster allowed six hits, including one to his former teammate at City High, Max Bishop, who was playing third base for Baltimore. After the game, Thomas’s fine effort on the mound was rewarded with a contract from the Buffalo club. However, he was not required to report to the Bisons until after he graduated from City High School. Tommy was a good student and had been considering enrolling in college. However, the early opportunity to play professional baseball steered him towards a career on the diamond.

Thomas was just an average pitcher during the three seasons he spent with Buffalo, winning a total of 30 games and losing 29. By the spring of 1921, the Bisons’ front office had grown disillusioned with Thomas and placed him on waivers. At that time, Oriole owner and manager Jack Dunn shrewdly purchased Tommy from the waiver wire for the bargain price of a $1000.

The Baltimore Orioles were coming off two consecutive International League pennants when Thomas joined the club in 1921. Tommy posted a record of 24-10 in his first year with the Birds, complimenting an already solid mound corps of Jack Ogden (31-8), Lefty Grove (25-10), Harry Frank (13-7), and Jack Bentley (12-1).

The Orioles dominated the circuit that year, winning 119 games, the second highest total in minor league history. However, injuries to Ben Egan, Jack Bentley, Joe Boley, Max Bishop, Merwin Jacobson, and Otis Lawry contributed to a disappointing loss to Louisville in the Little World Series that fall.

The high-flying Birds captured four more flags in a row with Tommy featured as one of the mainstays of the Baltimore pitching rotation. Thomas thrived under the tutelage of the Orioles’ owner-manager Jack Dunn, a former major league pitcher who knew how to get the most out of his young players.

Tommy held out for a better contract in 1925, and the issue wasn’t resolved with Dunn until the middle of April. The layoff didn’t affect his pitching in any way, as he went on to have his best season as an Oriole. The hard-throwing right-hander led the league with 32 wins, 268 strikeouts, 28 complete games and 354 innings pitched.

Jack Dunn, always knowing the right time to consummate a deal, sold Tommy to the Chicago White Sox at the end of the 1925 season for a reported $15,000. Thomas won 105 games while losing only 54 during his five years with Baltimore. He appeared in the Little World Series with Baltimore four times, going 4-4 in post-season play. Thomas’ lifetime pitching record in the International League was a stellar 138 wins, 85 losses and a 3.30 earned run average.

In his first year with the White Sox, Tommy finished second on the team in wins with 15. He held opponents to a .244 batting average, the lowest in the American League. Thomas also finished second in the loop in strikeouts per game. On September 25, Thomas beat Washington Senators ace Walter Johnson 2-1, earning a $2,500 bonus from Chicago’s frugal owner Charles Comiskey.

Thomas had his best year in the majors in 1927, winning 19 games and posting a career-low 2.98 earned run average. He also led the league in innings pitched. The following year, Thomas was a 17-game winner for Chicago and finished third in the American League in strikeouts for the second year in a row.

Tommy’s pitching fell off a bit in 1929, leading to a 14–18 record. Thomas posted a decent 3.19 earned run average that year and led the junior circuit with 24 complete games.

The 1930 campaign was not kind to Tommy. His father passed away during spring training, and he injured his elbow in an early season game against St. Louis. He continued to pitch through the pain, but a severe case of ptomaine poisoning put him out of action for an extended period of time. Although Thomas returned to the club, he never got on track, going 5-13 with a 5.22 earned run average.

Still bothered by arm problems in 1931, he managed to win 10 games (against 14 losses) in 43 starts. Thomas logged 245 innings on the mound that year, but a series of maladies, including a bone bruise on his arm and a throat infection hampered his ability to pitch effectively during the season.

Tommy’s pitching woes continued during the early months of the 1932 season, and on June 11 he was sold to the Washington Senators. From 1926 through 1932, Ted Lyons, Red Faber, and Thomas were the backbone of the Chicago White Sox pitching staff. The team went through five different managers during that time and never finished higher than fifth in the American League standings.

When healthy, Thomas was a big-game pitcher who used his hard-breaking curve ball to set up his lively fastball. Unfortunately, arm troubles plagued him for most of his career with the White Sox. Tommy stepped up big with some memorable mound performances in the Chicago City Series that was played at the end of the season between the White Sox and Cubs. In 1926, Thomas lost a 1-0 game to the Cubs on an error by the second baseman in the eighth inning. In 1928, Tommy struck out 13 batters in a 14-inning loss after giving up an unearned run with two outs in the bottom of the ninth. Three days later, he blanked the National Leaguers on two hits in front of 48,000 fans at Wrigley Field. In 1930, Thomas went the distance in a victory over his cross-town rivals, allowing just six hits. The following year, he was the winning pitcher in the game that clinched the series.

During his tenure with the White Sox, he roomed for a year with future Hall of Fame pitcher Ted Lyons. Neither of the men used alcohol or tobacco. When asked by Bob Maisel of the Baltimore Sun what the two pitchers did in their leisure time, Thomas replied, “Oh, we double-dated some. We both liked good food, good restaurants, good theatre, even the opera. We always found something to do.”

Thomas was still having arm problems during the summer of 1932 but still managed to win games on three consecutive days for the Senators in the middle of July. The first two victories were in relief, and on July 16th he threw a five-hit shutout against the St. Louis Browns. At the end of the season, he had surgery to remove a growth in his pitching arm and to relieve what was reported in the newspapers to be a locked elbow. The numerous innings that Tommy pitched during his early days on the mound contributed heavily to the myriad of injuries and maladies he struggled with later in life.

Tommy was a decent pitcher for Washington over the next few years, but the harsh reality was that his arm was never the same after the 1932 operation. The Senators captured the American League pennant in 1933 but lost out to the New York Giants in the Fall Classic. Thomas, playing in his first and only World Series, made two brief relief appearances, allowing one hit in a little over an inning of work.

On May 10, 1935, Washington traded Thomas and pitcher Ray Prim to the Philadelphia Phillies for Snipe Hansen. Tommy appeared in four games for the Phillies before being optioned to Baltimore. He played in 17 games for the Orioles in 1935, winning three and losing two.

The St. Louis Browns purchased his contract from the Phillies in January 1936, and Tommy won 11 games for a Browns team that finished 38 games under .500. The next season, working mostly out of the bullpen, he was released by the Browns on July 11, 1937. The following day, the Boston Red Sox signed him to a contract. The right-hander, who was now at the end of the line, appeared in nine games for the Red Sox and was released at the end of the year.

Thomas’ major league days came to an end after his short stay with the Red Sox in 1937. He finished his major league career with a pitching record of 117 wins and 128 losses. The veteran pitcher played one last season in the minors in 1938, splitting time between Knoxville and Chattanooga of the Southern Association.

Tommy served as a player-coach on Rogers Hornsby’s staff while he was a member of the Chattanooga team. The Dunn family (owners of the Baltimore Orioles) hired Hornsby to manage their ballclub the following year, and Thomas went with him to Baltimore. The Orioles performed poorly under Hornsby, who was let go after just one season. The Dunns, noting the former pitcher’s ties to the city and its past days of winning baseball, hired him as the team’s new manager in 1940.

Thomas was well aware that Baltimore and its surrounding areas were loaded with talented baseball prospects. During his tenure with the Birds, he signed numerous hometown stars to the Oriole roster. Ray Flanigan, Gordon Mueller, Russ Niller, Dick Waldt, and Harry Imhoff were just a few of the local standouts that played for Baltimore when Tommy was the manager of the team.

Thomas was constantly searching for a winning combination on the field. This task was made more difficult due to his obligations of shuttling players back and forth to the club’s major league affiliates in Philadelphia, Cleveland, and later St. Louis.

In 1943, Tommy was named general manager by the Oriole Board of Directors.

The Birds started out playing good ball in 1944, but tragedy struck in the early morning hours of July 4, when Oriole Park was burned to the ground. Even though the wooden grandstands were hosed down with water after every home game, modern-day sleuths surmise that a partially lit cigar or cigarette may have been the cause of the fire.

The team’s business records and trophies plus their equipment and home uniforms were all lost in the maelstrom. The ball club was forced to move to Municipal Stadium on 33rd Street to finish out the season. Due to wartime shortages, the Orioles were unable to replace all of their equipment and in some instances, the players had to borrow bats and gloves from the opposing clubs. Orioles first baseman Bob Latshaw later recounted that the other teams in the league always gave them the heaviest and oldest bats in their rack.

The Birds had been on a roll before the fire, but the tough hand they were dealt inspired them to even greater heights. The Orioles were able to battle their way past Newark for the 1944 International League pennant by mere percentage points. At one point during the 1944 season, Baltimore swept four straight doubleheaders from the Montreal Royals. The Flock continued their winning ways in the postseason, defeating Buffalo and Newark in the Governors Cup playoffs. The Birds stayed hot in the Little World Series, knocking off the American Association champion Louisville Colonels in six games. One of the games in Baltimore drew 52,833 fans on the same day that the World Series in St. Louis attracted 31,630. Thomas in a true show of generosity refused to accept his share ($2,500) of the series money. He said in the press at that time that his players, not he, had earned the money.

The Sporting News named Thomas Minor League Manager of the Year for his outstanding accomplishments. Tommy made his last two mound appearances in professional baseball for Baltimore that year. At the age of 44, he pitched in a pair of games, giving up four hits in two innings of work.

For the next couple of years, times were good for Thomas in Baltimore although his Orioles were never able to recapture the magic of the 1944 season.

The Birds’ skipper was generally well liked by his players, his managerial style being described as somewhere between the fire-eating John McGraw and the soft-spoken Connie Mack. In a 1945 interview Tommy replied, “Oh, I give the boys hell once in a while but gosh just ask them what I’m like.”

The 1949 campaign started out well for Thomas and the Orioles. Unfortunately, an incident occurred a few days into the season that marked the beginning of the end for Baltimore’s esteemed manager.

The Baltimore fans were generally supportive of their home team in the post World War II era. However, there were a few Oriole Park patrons who had been riding Thomas and his players since opening day of the 1949 season. The situation finally came to a boil in a game against the Toronto Maple Leafs on April 26. In the top of the third inning, Toronto first baseman Bill Glynn smacked a hot shot past Orioles third baseman Ellis Clary that plated two runs and tied the game. Clary had recently been shifted from his regular position at second base and had misplayed a grounder earlier in the inning. The batted ball that accounted for the two Toronto runs was ruled a base hit by the official scorer, but not everyone in the crowd agreed.

It was at this time that a fan who was seated a few rows behind the Orioles’ dugout, began a profanity-laced tirade against Clary in an extremely threatening manner. This particular ne’er-do-well had been heaping abuse on the Baltimore players since the beginning of the game. At the end of the inning, Clary remarked to Thomas that he felt threatened by the man and did not feel comfortable taking the field for the next inning. Thomas, who had enough by now, stepped out of the Baltimore dugout and pointed out the culprit to Clary, telling him to “go get him.” Clary jumped into the stands, but two Baltimore City Policemen and a plainclothes officer stepped in before the Oriole infielder could exact some rough justice on his antagonist. The belligerent fan was refunded his money and escorted out of Municipal Stadium for his indiscretions. Unfortunately, this brief and uncharacteristic lapse of good judgment by the Orioles’ manager would have serious repercussions.

The International League did not tolerate such behavior and the punishment was swift. Thomas received a five-game suspension, and Clary got hit with three by the loop’s President, Frank “Shag” Shaughnessy. The umpires on duty that day gave Shaughnessy a detailed account of the incident, all agreeing that the man had been violently abusive for the entire game. President Shaughnessy spoke publicly about the incident, saying he sympathized with Thomas and Clary but couldn’t condone a player going in the stands after a fan for any reason. Looking back years later, Tommy spoke about the incident remarking, “Bad thing to do, you know you can wear out your welcome.”

On May 2, the Oriole Board of Directors met and unanimously voted not to censure Thomas for the incident.

A few weeks later on May 21, Thomas resigned as manager but stayed on as the team’s general manager and vice president. He informed majority owner Jack Dunn III and team executive George W. Reed of his decision over lunch the day after returning from an unsuccessful road trip. Thomas’ Birds, who started the season playing good ball, lost 12 out of their last 16 games, dropping them all the way down to last place in the standings.

At the time of his resignation, Thomas spoke to the press saying, “I decided on this move in the interest of all concerned. And I include the players themselves in this. They have been under terrific pressure because of the way things have been going. They have been trying so hard they are all tightened up. It was my decision and I came up with it suddenly this morning. I think it will react favorably all around. The players have been under pressure and this club, in my opinion, can win. It was a move I have contemplated for three years. I have always wanted to operate a team from the front office. This will give me an opportunity to really scout the players we need and to further build up relations with other clubs.”

Thomas ended his minor league managerial career with a record of 638 wins and 734 losses. He continued in his front office role with the Orioles until the end of the 1949 season. At that time, Tommy’s plans changed, possibly due to problems within the organization, and he resigned from all positions on the team.

In November 1949, the Boston Red Sox hired him as a scout. In 1957, Red Sox farm director John Murphy named Tommy the general manager of the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. After a short run with the Millers, he returned to the Red Sox scouting staff, where he remained until he retired in 1973.

While taking a drive one day, Tommy and his wife, the former Alice Flemming, were smitten with the scenic Pennsylvania countryside of southern York County and in 1962 they purchased a home in Dallastown.

In a 1985 interview with Baltimore Sun reporter Bob Maisel, Thomas said that he stayed in touch with the game during his retirement years by following the box scores in the newspapers. Thomas, who once tossed 72 complete games in the span of three seasons, cringed in disbelief when he read about a pitcher going five strong innings before coming out of a game. In regard to modern players’ lack of endurance, Thomas said, “I am a little fanatical about how long pitchers are going. That is what I look for the closest in the box scores. It can tell you a lot.”

Asked about current players [1985 interview] he had his eye on, Tommy replied, “I like this kid Yount who plays for the Brewers. He must be good with stats like that. And Cal Ripken’s kid. I met Ripken [Sr.] once in North Dakota. We went to dinner. Nice man. His kid must be a pretty good ball player huh?”

Recalling the best players from his era, Thomas recounted that Yankee great Babe Ruth and Detroit Tigers outfielder Harry Heilmann hit him the hardest. The Bambino once launched one of Tommy’s offerings clear out of Comiskey Park, and Heilmann, the last right-hander to hit over .400, led the American League in batting four times.

Thomas picked Ty Cobb over Ruth as the greatest player, saying, “It gets to be just a matter of opinion. You could go with Ruth because he was a great pitcher before he started hitting all those home runs. But Cobb could do so many things and such a competitor, he still gets my vote. He was the best I ever saw at handling the bat. He hit bullets down the left-field line as hard as if he had been a right-handed pull hitter. His bat control was amazing.”

Over the years, Tommy received many well-deserved accolades, including induction into the City College of Baltimore Hall of Fame, Maryland Sports Hall of Fame, International League Hall of Fame, York Area Sports Hall of Fame, and the Maryland Professional Baseball Players Association Shrine of Immortals.

On April 22, 1988, the 88-year-old Thomas suffered a fatal heart attack while gardening in his backyard in Dallastown. His viewing was held at the Berg Funeral Home in Red Lion, Pennsylvania. After the service, he was interred at Druid Ridge Cemetery in Pikesville, Maryland. His wife Alice died in 1982, and the couple had no children.

Regarding Tommy’s passing, baseball writer Bob Maisel wrote in the Baltimore Sun, “In a time of what was supposed to be a rough and tough era of the sport, Tommy was a gentleman and he remained that way throughout.”

Sources

The Baltimore Underwriter 1917

Baltimore Sun 1917-1918-1925-1984-1985-1988

Bob Maisel Baltimore Sun interviews 1984-1988

John Eisenberg Baltimore Sun interview 1985

Washington Post 1944

The Sporting News 1988

Blair Jett for contributing the photograph of Tommy Thomas

Marshall Wright, The International League Year by Year Statistics (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 1991).

Full Name

Alphonse Thomas

Born

December 23, 1899 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

April 27, 1988 at Dallastown, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.