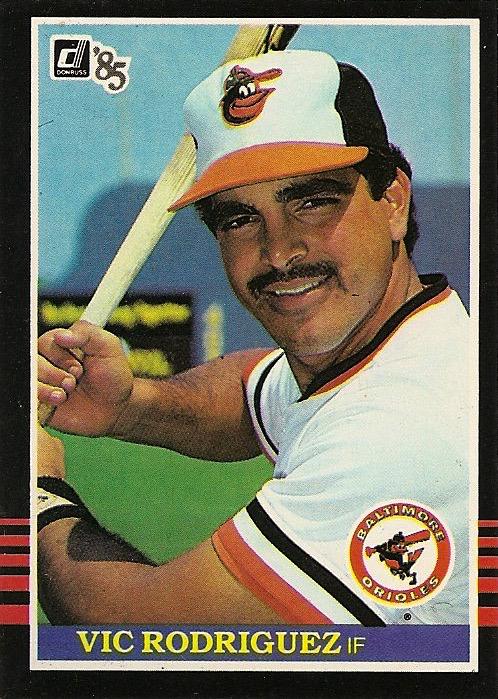

Vic Rodriguez

At 15 Victor Rodriguez started playing competitive adult baseball against men twice his age. Before the season was over, he was a minor leaguer with the Baltimore Orioles. He spent parts of two seasons in the major leagues and played in Organized Baseball for 19 years.

At 15 Victor Rodriguez started playing competitive adult baseball against men twice his age. Before the season was over, he was a minor leaguer with the Baltimore Orioles. He spent parts of two seasons in the major leagues and played in Organized Baseball for 19 years.

Victor Manuel Rodriguez was born on July 14, 1961, in New York City. His parents, Luis and Inés Rodriguez, natives of Puerto Rico, were working in New York. In 1966 they returned to Puerto Rico. Victor lived with his parents, sister, and four brothers on the island’s eastern shore in Naguabo, near the El Yunque National [Rain] Forest.1 From May to September it rains every day, so locals are known as “The Wet People,” said Rodriguez’s younger brother Ahmed.2

“The reason I played baseball was because of my dad,” Victor said. “He was a baseball fanatic. My mother met him in New York3 on a baseball field. That’s how I got that love for the game.”4

“My brothers and I played with rocks,” he added. “We played with a broomstick. We’d play with bottle caps. Whatever we’d find we’d hit. I have some scars back here [on my head] because we used to hit rocks.” His mother, Ines, said, “When he got injured he would get mad and sad because he couldn’t play.”

Rodriguez’s earliest memory of organized baseball was getting a uniform for the Police Athletic League when he was 10. “We were always playing baseball. I remember taking a break in school from one class to another, they’d give us a break. We’d go and play baseball forever. Ten minutes. Twenty minutes. We’d make a team, play as long as we could, then go back to class. For lunch we were back on the field playing baseball.”

Luis Rodriguez worked in an aluminum factory. After his daily shift, and on weekends, he’d play baseball with Victor, said brother Ahmed. “Our dad was hard on us [siblings], so everyone would be good at what they wanted to be.”

At 15, Rodriguez joined Cariduros de Fajardo in Puerto Rico’s esteemed AA League, for the 1976-77 winter season.5 A teammate, outfielder Richie Figueroa, who signed with the San Francisco Giants in 1980, said, “He was playing with men. We played with guys 40 years old, 35 years old, 25 years, old, guys that played for the national team. The league was really competitive.”

Peter Montalvo, another Fajardo teammate, recalled, “We were playing Vieques. You have to take a ferry for 45 minutes. A little island on the east coast. He got a base hit to left field on a groundball and he kept on going to second base and he dove in, safe. I’ll never forget that.”

“One thing that caught the attention of the people, especially the scouts, was his age, 15 years old,” said Figueroa. “He was handling shortstop like he was a veteran already in the league. Then people started talking about him, ‘good hands,’ ‘good bat.’ He was really smart.”

“He adapted [to the league’s faster pace] and got signed immediately,” said Montalvo. Legendary Puerto Rico scout Luis Rosa worked with Orioles scout Tom Giordano to sign Rodriguez before the AA League season was over. On February 11, 1977, at 15 years and 7 seven months, Rodriguez signed for $29,000 and a $7,500 education incentive bonus.

“It was more out of necessity,” said Rodriguez. “We needed the money and I wanted to play baseball. We redid the house. I remember we didn’t have a bathroom. We didn’t have a washer and dryer. My father bought a car. We owed a lot of money for groceries.”

Because Victor was a minor, his father traveled with him to the mainland to sign the contract. Luis saw his son play during spring training in Miami. In June Rodriguez, not quite 16, was 1,600 miles from home, playing for the Orioles rookie team in the mining town of Bluefield, West Virginia.

He was on his own. His family did not have a phone. Letters took a week between Bluefield and Naguabo. “I never got homesick because I was doing something I wanted to do,” said Rodriguez, remembering his mother’s reassurance. “She always encouraged me to put my faith in baseball.”

Rodriguez managed the cultural transition and teammate age difference. “It was easy. … We communicated out loud [without cellphones and email]. So I thought at the time I knew everything about them and they knew everything about me. … We were more like a family.”

His mother did not worry. “Since he was a little boy he had the maturity to think about his future and his family’s future,” she said.

The biggest surprise in Bluefield was an ordinance regulating the work hours of minors. “If you were under 18 you couldn’t work past 9 o’clock,” said Rodriguez. “So when it got close to 9 o’clock, they took me out of the game!”

Rodriguez hit .293 and was among the team’s leaders in batting average, slugging, and OPS. The Orioles organization wanted older infielders to get playing time on defense, so Rodriguez DH’ed. He played six games at shortstop and third base.

The offseason was filled with transition. Victor’s father, Luis, was diagnosed with cancer and died at 47. Victor, now 16, played the first of 19 seasons in the professional Puerto Rican Baseball League.6 He also met Elba Aquino, whom he would later marry. She would share and support his long minor league journey. “She was behind everything good that happened,” said Rodriguez.

Seven-year-old Ahmed looked forward eagerly to his older brother’s games. With his mother and family, Ahmed would travel the island to watch Victor. With the passing of his father, Ahmed said, “I saw him like my dad. I was just 7 or 8 years old, and he was the one who took care of me.” Victor’s baseball salary also became an important source of income for the family.

Rodriguez progressed through the Orioles system, hitting over .300 four consecutive seasons. He batted and threw right-handed and played most of his games at second and third base. In 1978 he was the Appalachian League All-Star DH.7 In 1981 he received the Orioles’ Clyde Kluttz Organizational Player of the Year Award.8 He reached Triple-A Rochester at 20 in 1982 and was added to the Orioles’ 40-man roster.9 In 1983 he was the Double-A Southern League’s All-Star second baseman.10

Rodriguez and Elba married in 1983. His nearly annual minor-league relocation became a family affair. Rodriguez said, “She always found a way to get there,” with their sons Victor and Miguel, born in 1985 and 1990 respectively. Elba also worked, said Rodriguez, to help pay their apartment rent plus the bills from their home in Puerto Rico, and she raised the boys. “You have to have a wife like that,” he said.

Rodriguez said manager Lance Nichols was a major influence on him at Miami (Class A Florida State League) and Triple-A Rochester. “He always wanted me to do the right thing and he always brought me early work,” said Rodriguez. “I thought he hated me, because he was always all over me. But this guy really cared about me. Every day he wanted to work and do things the right way. That’s when you realized even though he never showed that affection, he cares.”

Rodriguez established the approach that would sustain his playing career and build his coaching skills. “I never was in a position in which I doubted I was good enough to be playing baseball or had negative thoughts coming into my mind because I wasn’t doing well,” he said.

At the end of his first full season at Rochester in 1984, Rodriguez was called up in September. When he was told of the call-up by manager Frank Verdi, Rodriguez recalled, “I was a new person.” In Naguabo, Ahmed said the town celebrated its first major leaguer.

It may have been a calming influence for Rodriguez to travel to Detroit with major-league veteran Ron Jackson, who was also called up, but it did not carry into the game. There were over 34,000 fans in double-decked Tiger Stadium on September 5 as the American League East Division leaders faced the defending World Series champion Orioles. “The field was packed,” said Rodriguez. “I remember ‘the wave’ was a big thing.”

In the ninth inning, when Rodriguez ran for Ken Singleton, he was so anxious that he barely took a lead at first base.

He pinch-ran twice more before getting his first hit in New York on September 18 against Clay Christiansen of the Yankees. He was a midgame replacement for second baseman Rich Dauer and singled between short and third in the ninth, his second at-bat of the game. “The ball looked like zig zag and it went through the infield,” Rodriguez recalled.11

Two days later in Boston, in his first start, Rodriguez faced Red Sox pitcher Al Nipper. “He threw me a 3-and-2 sinker inside and I swung,” he said. “I missed it and it hit me in the shin. I’ve got the picture at the house. … So the umpire called a strike and called me out. I said, “The ball hit me” and he said, “But you swung and you struck out.” After a popout in the third, he doubled twice and singled, scoring twice and driving in a run in a 15-1 Orioles win. He started three more games, and had three more hits before the end of the season.12

In 1985 Rodriguez was traded to the San Diego Padres for infielder Fritzie Connally and hit .312 for the Triple-A Las Vegas Stars. As a minor-league free agent in 1986, he signed with the St. Louis Cardinals and played for Triple-A Louisville, hitting .272, then .294 in 1987. A free agent again in 1988, he signed with the Minnesota Twins and hit .288 for the Triple-A Portland Beavers. It was his 12th season and Rodriguez had hit over .300 at every level of the minors and never below .262.

As Rodriguez changed teams, he said, his teammates would ask, “‘Why didn’t you play in the major leagues? You really should be playing more [in the majors],’ and I said, ‘Because I could not call myself up.’”

Rodriguez might have been disappointed, but he stayed focused on results. “If you get too comfortable or frustrated or show emotion, you’re only hurting yourself and the way you play the game,” he said.

In Portland in 1989, Rodriguez was again hitting .300. “He was outstanding in the clubhouse, a solid human being on and off the field,” and reliable defensively at third base, said manager Phil Roof. Rodriguez batted third and was among the team leaders in average, total bases, runs, and OPS.

“I was sleeping and the phone was ringing,” said Rodriguez. “I grab the phone and Phil Roof said, ‘Tomorrow you have to be in Milwaukee.’ I said, ‘What for? Why do I need to go to Milwaukee?’ And he said, ‘Because you got a call-up to the major leagues!’”

The Twins third baseman, Gary Gaetti, was injured so Rodriguez was needed for a series against the Milwaukee Brewers. On July 21 he arrived close to game time and found out he was in the lineup, batting second in front of Kirby Puckett.

“My baseball stuff didn’t show up,” said Rodriguez, “so Kirby Puckett let me use his shoes and Gary Gaetti, I used his glove.” He singled in the first off Teddy Higuera, his only hit in four at-bats. Over the next five games, he started once and was a pinch-runner and late-game substitute for Gaetti. He had five hits in 11 at-bats.

At Yankee Stadium on August 1, Twins manager Tom Kelly called Rodriguez to his office. “I remember Tom Kelly not even looking at me,” said Rodriguez. “He told me, ‘You paid your dues but we made a big trade.”

Frank Viola, a 24-game winner in 1988, had been sent to the Mets for pitchers David West and Rick Aguilera. Both pitchers needed roster spots, so Rodriguez was sent back to Portland.

“I took it like it was part of the game,” said Rodriguez. “You feel appreciation for all the opportunities that you get.”

“Í knew he was disappointed,” said Roof, “but it didn’t affect his game play. He tried to get back to the major-league level.” Rodriguez finished 1989 as Portland’s top hitter, leading the team in batting average and total bases.

Rodriguez’s 1990 season was limited to 12 games by a herniated disc, but with physical therapy he bounced back with another .300 season in 1991. The Twins offered him a coaching position, but Rodriguez still wanted to play, as he had just hit .300 for the seventh time in 16 years.

He signed with the Italian Baseball League for 1992, but before the season began, he was traded. When Rodriguez learned his salary was reduced, he declined to go Italy and instead played in the Mexican League for the Tabasco Olmecas. After two months, the Phillies bought his contract. He returned to Triple A with Scranton and hit .277 in 48 games.

During his annual return to the winter Puerto Rican Baseball League, Rodriguez remained an offensive force. “He was a dangerous hitter,” said Jose Hernandez, who played against him in Puerto Rico in the early 1990s and in 2019 was a major-league coach with the Orioles. “We would treat him like he was Barry Bonds. It was better to walk him or pitch around him to get to the other guys because he was a good hitter.”

Rodriguez’s hitting preparation and execution also caught the attention of another 1990s Puerto Rico opponent, Jose Flores, in 2019 the Orioles third-base coach. “He was a hitting freak,” said Flores. “All about hitting … studying swings and mechanics and pitchers and their tendencies, how they tip, for you to be able to have a little bit of an edge.”

“He took a lot of pride in not striking out a lot and that’s probably why he was so successful,” said Flores. “He just wanted to put the ball in play when he had two strikes. And before two strikes he just wanted to do damage. If there was a tough pitcher on the mound, he could change his approach on trying to put the ball in play, but still make hard contact. Not everybody can do that.” In the minors Rodriguez never struck out more than 53 times in a season.

Rodriguez also emerged as a mentor, Flores said. “It’s very common, especially during winter ball, for players to get away from their own routines, meaning during batting practice just going for the fences pretty much on every swing. You did not see that with Victor. Every time that he saw one of his teammates, or a guy that he really appreciated, a true friend, he would just approach him and say, ‘Hey. Go about your business as if you were in the States, as if you were in the big leagues.’”

In 1993 the Phillies asked Rodriguez, now 31, to be a player-coach, with limited playing time. Rodriguez agreed but early in the season he was asked to start a game against Pawtucket pitcher Aaron Sele. “First at-bat I hit a home run. I ended up playing 98 games in a row. I got close to 500 at-bats [471 plate appearances] for a guy who wasn’t going to get 100 at-bats.” Rodriguez hit over .300 again, finishing fourth in the league at .305.

After playing in 84 games in 1994 with Triple-A Edmonton (Marlins), Rodriguez started the 1995 season with Triple-A Pawtucket (Red Sox). In May Red Sox coach Luis Aguayo advised Rodriguez that planned personnel moves would drop him from the roster. “I said to myself, ‘I’ve never been released. I’m not about to get released here.’” said Rodriguez. 13

Rodriguez discussed coaching with the Red Sox front office. He transitioned almost instantly, this time from player to coach. “They came in and told me tomorrow you go to Fort Myers and meet with your team. From Fort Myers I went to Utica in the New York-Penn League.”

His playing career was over. In 17 major-league games he had 12 hits in 28 at-bats. In 19 minor-league seasons, with seven organizations, he hit .295 with 1,905 hits in 1,759 games.

From 1981 to 1991, Rodriguez’s path to the major leagues was often blocked by established players and All-Stars. “I’ve never heard him say a negative word about that situation,” said Arnie Beyeler, who coached with Rodriguez for many years with the Red Sox. Based on the defensive positions played by Rodriguez in Double A and Triple A during those 11 years, the following starters played in front of Rodriguez in the majors: Rich Dauer, Graig Nettles, Garry Templeton, Tim Flannery, Terry Pendleton, Gary Gaetti, Kent Hrbek, and Chuck Knoblauch.14

Rodriguez learned the craft of coaching. “You just don’t become a coach from one day to another,” he said, recalling the guidance he received from Red Sox scout, coach and minor-league manager Felix Maldonado. “He was really big on communication … coaching and repeating and never gave up on players. You do it one time, two times, three times and then 1,000 and 1,001. Never stop teaching … because they are professional doesn’t mean that they don’t need to learn.” Rodriguez would be with the Red Sox for the next 23 years, all but three as a hitting instructor, coach, or coordinator.15

“At the lower [Class A] level, there is more teaching,” said Rodriguez. “It’s more specific about how to become a professional ballplayer. At Double A and Triple A when they’ve played so many years we help them stay consistent and guide them and help fulfill their dream to play in the major leagues. It’s more about controlling what they can control and trust all the work they have done to get there. And to stay consistent so if there is an opportunity, they are ready for it.”

On the field, coaches watch players, but Rodriguez said players watch coaches too. “You have to be consistent with everybody. Players look and say, ‘You do it different with this guy.’ Approaching everybody the same helps me gain the trust of everyone. … I never took or treated anybody different than the other. … Prospects and nonprospects the same.”

Nelson Castro, in 2003 a 27-year-old with the Double-A Portland Sea Dogs, remembered Rodriguez as a minor-league hitting instructor. Rodriguez told him to keep his hitting approach simple. “Think about what you are going to do in the cage and bring it to the game,” Castro said Rodriguez advised him. “In the game don’t be thinking. Just see the ball and hit the ball. … You want your mind to be nice and clear. … He was a good friend. It was easy for you when you are comfortable around somebody that you know.”

Rodriguez interviewed for Red Sox hitting coach for 2013. When Greg Colbrunn was hired, the Red Sox offered the team’s new assistant position to Rodriguez. The two-coach approach produced a major-league-leading 5.27 runs per game and a World Series championship.

Colbrunn said they had “a great relationship since day one,” as he focused on video and scouting. Rodriguez worked mostly in the batting cage before and during the game.16 “Somebody’s got to stay in the dugout,” said Rodriguez, “and the other person’s got to be in the [indoor] cage working with the kids so guys that he works with before the game, I have to work with them during the game. The main thing is whatever they’re doing during the game, it’s the same thing we’re doing before the game, so it’s beneficial.”17

Rodriguez applied his successful hitting approach. “We worked to get our players ready to hit all the time,” he said. “It wasn’t about taking pitches, it was about getting your pitch and being aggressive with it. We know the importance of getting on base, whether a hit or a walk, and making contact with two strikes.”18

Beyeler, the first-base coach for the 2013 Red Sox, said Rodriguez’s connections with coaches and knowledge of players was a huge asset. “He’s got relationships with everybody in the game. He knows everybody. He’s played for everybody. They’ve played for him or he knows them. The relationships are great.”

In 2014, 21-year-old rookie shortstop Xander Bogaerts and the Red Sox struggled. In early June Bogaerts was hitting around .300 but the team’s record was stuck below .500. Free agent Stephen Drew was signed to play shortstop. Bogaerts was moved to third base, where he had only 19 games of professional experience. His average plummeted. Everyone wanted to help, said Bogaerts, so he listened to them all.19

In late August, Bogaerts concluded that Rodriguez knew him best.20 Rodriguez said Bogaerts told him, “‘I’m going to listen to you and only you.’ So we decided to start with a routine. … That helps you prepare for the game and to be consistent and do it every day. It’s a consistent routine so that if you are in a funk, you can get out of it.”

Rodriguez said that the day Bogaerts started the new drill he went 4-for-5 with a home run.21 “And from that day until I left the Red Sox we did the routine every day,” said Rodriguez.

With elite hitter David Ortiz, Rodriguez found pregame preparation was all Ortiz needed. “He trusts what he does here [in the batting cage],” said Rodriguez. “I remember some days he’d say he didn’t want to hit on the field [for batting practice]. ‘Let’s do our drill here [indoors],’ he’d say, ‘That’s enough for me.’” Ortiz never hit in the indoor cage during a game, Rodriguez said. “Nothing. Just watch TV. Take his shoes off. Wait until his next at-bat.”

When Chili Davis was hired by the Red Sox as hitting coach in 2015, Davis kept Rodriguez as assistant. Their relationship dated back 14 years as teammates and coaches. Davis said of Rodriguez, “There’s a guy that works hard, he’s organized, and we talk the same language when it comes to hitting.”22

After Red Sox manager John Farrell was fired following the 2017 season, the Red Sox told Rodriguez he could stay with the team until his contract expired after the 2018 season. Under a new manager, however, the club’s president of baseball operations, Dave Dombrowski, could not assure Rodriguez that he would retain his assistant hitting coach role. Within a month, Rodriguez had been hired by the Cleveland Indians as its assistant hitting coach. Indians manager Terry Francona said of Rodriguez in 2019, “He has been a valuable addition to our staff and has developed a strong rapport with our position players. He is a resource for us on players he has formerly worked with and has a strong presence and has developed great relationships with our Latino players.”23 In 2018, with hitting coach Tyler Van Burkleo, the Indians were second in the AL in runs and third in hitting.

In his 25th year as a coach, Rodriguez continued to stress trust and communication. “From the moment you step in the clubhouse (the players) are looking at you,” he said. “They are deciding if you have the personality, the energy, and the willingness to be there for them. This game is about trust. It doesn’t mean anything if you have knowledge and the players don’t trust you.”

Arnie Beyeler said Rodriguez’s strongest asset was how he developed “relationships with guys and understand players and what makes them tick, and whether you need to pat guys or whether you need to push guys.”

With players from about 20 countries, Rodriguez has transitioned from baseball’s most common spoken languages, English and Spanish, to the universal language of hitting. “I’ve had players who speak Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese. They didn’t speak English,” he said. “It’s how do you get them to understand the message. Sometimes I’m talking to a Latin guy in Spanish but I can get the Japanese guy to understand me more than the Latin guy with whom I speak the same language. Much of the time I didn’t say a word, but I managed to do things in the cage or with the tee or with soft toss that the guy understands.”

Rodriguez’s positive attitude brings the best out of players over the long baseball season, said coach Jose Hernandez. “He’s always got a great smile. … That’s the way you have to be teaching, especially as a hitting coach. You have to work with those guys every day.”

Beyeler said Rodriguez was one of the first coaches to arrive at the ballpark. “He’s spent more time at the field than anybody I know.” And Rodriguez used that time to become the batting practice pitcher of choice. “Vic is the best thrower in the organization – ask anybody,” said Jackie Bradley Jr. “He can put the ball right where you want it.”24

Preparing for the 2013 postseason, Red Sox second baseman Dustin Pedroia insisted that Rodriguez throw batting practice to the starting lineup. Rodriguez recalled, “Pedroia said to me, ‘Do you want to win the World Series? You need to find a way to throw to us,’”25 The Indians’ Carlos Santana asked Rodriguez throw to him in the 2019 All-Star Game Home Run Derby.

Batting practice can also be a diagnostic and teaching tool, said Rodriguez. “As a hitting coach, you can get more accomplished by throwing to a hitter than talking to him. You pick up a lot of things when you pitch to them.”26

Rodriguez also stayed current with video applications like opposing pitcher tendencies and prior hitter/pitcher outcomes. “If it is something new and something different, if you want to stay in the game you’ve got to be on board,” he said. “If you are not on board, you are not in the game.”

So Rodriguez has learned to accommodate the involvement of hitters’ offseason and home-based hitting instructors. “We have to be on board and try to help to go their way so they can come our way,” he said. Giving a hitter feedback from television can be helpful, but the daily perspective at the ballpark is most valuable. “(The outside instructor) doesn’t know if you slept well that day. He doesn’t know if you’re sick. He doesn’t know all the things that I know, why you have success and why you don’t have success.”

After Rodriguez’s long days of coaching, his family was always next, especially during his years with the Red Sox. The family lived in Fort Myers, Florida, Boston’s spring-training home. Like his father, Rodriguez shared with his sons his love of baseball.

When Red Sox workouts were over, Rodriguez would throw batting practice to Victor Jr. and Miguel for an hour or more, said Beyeler, if the two boys had not already been rotated into the Red Sox batting-practice groups. If his sons had games, Beyeler said, “Elba was always in attendance making sure the boys were where they needed to be. Victor would always go straight from our field to wherever they were playing, seldom missing an inning if he was in town.”

In 2019 Victor Jr. was a scouting supervisor for the Tampa Bay Rays.27 Miguel was drafted by the Red Sox in the 36th round of the 2012 draft as a catcher and played in the minor leagues for two years.

Reflecting on his baseball career, Rodriguez said the support of Elba, his wife, was unwavering. “She’s the only reason I stayed in the game. She never asked why or when we are leaving and where we were going,” he said.

“Baseball has been really good to me and my family,” he said. “Forty-three years, beginning in Puerto Rico, and I never finished high school. I have been fortunate to be part of a major-league team and part of the World Series. You can only thank the organizations that gave me the opportunity.”

Asked if he ever got frustrated with his brief major-league service, Rodriguez said, “Never … because I did everything I could. And I knew I gave everything I could. At the end of the day I could not make the decision to get called up to the major leagues.”

But when that first joyous promotion to the major leagues occurred in 1984, brother Ahmed recalled precisely what followed the Orioles’ decision. The proud citizens of Naguabo wanted to name the local baseball field after Victor. Instead, Victor said the field should be named after his father, Luis.

Last revised: December 9, 2019

Acknowledgments

Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet were primary sources for this biography. While working on this biography the author learned that one of his Boston Amateur Baseball League teammates, Peter Montalvo, was a teammate of Victor Rodriguez on the 1976-77 Cariduros de Fajardo. Another Cariduros de Fajardo teammate of Rodriguez, Richie Figueroa, was an umpire in the league. The author also learned that his hitting instructor, Nelson Castro, had been coached by Rodriguez during his minor-league career. Since 2002 Rodriguez has been a coach and instructor at a baseball camp attended annually by the author.

This article was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Len Levin, and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Personal Correspondence

Arnie Beyeler, personal interview, August 16, 2019; email June 30, 2019.

Nelson Castro, personal interview, June 24, 2019.

Richie Figueroa, personal interview, June 26, 2019.

Jose David Flores, personal interview, August 16, 2019.

Terry Francona, email, forwarded by Bart Swain, Indians director of media relations, May 28, 2019.

Jose Antonio Hernandez, personal interview, August 16, 2019.

Peter Montalvo, personal interview, June 26, 2019.

Phil Roof, phone interview, June 19, 2019.

Ahmed Rodriguez, phone interview, July 29, 2019 with follow-up text messages.

Ines Rodriguez, phone interview, translated by Ahmed Rodriguez, July 29, 2019.

Victor Rodriguez, personal interviews, May 28 and September 9, 2019, with follow-up email and text messages.

Notes

1 El Yunque National Rain Forest is the only rain forest in the US Forest System.

2 Unless cited in these notes, comments from players and associates of Rodriguez were obtained in personal, telephone, and email interviews. The interviewees are listed in the Sources section.

3 Ines and Luis met on Randalls Island, one of New York City’s largest parks for sports and recreation.

4 Unless otherwise noted, comments from Victor Rodriguez come from personal interviews on May 28 and September 9, 2019, with follow-up email and text messages.

5 The team was based in Fajardo, about eight miles northeast of Naguabo. Cardidus translates to “hard face.” The team’s logo is a baseball player with a fierce face. The Superior AA league was founded in the 1930s, according to its website.

6 From 1977 to 1996 Rodriguez played for five teams in the Puerto Rico Baseball League, now known as the Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente: Bayamón Vaqueros, Santurce Cangrejeros, Lobos de Arecibo, Leones de Ponce, and Criollos de Caguas.

7 “Appalachian League/Rookie Kudos,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1978: 39.

8 ESPNBoston.com, “Rodriguez Hired as Assistant Hitting Coach,” November 30, 2012. https://www.espn.com/blog/boston/red-sox/post/_/id/23854/victor-rodriguez

9 “Bumbry Not Ready to Toss in Towel,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1982: 60.

10 “Appalachian League/Rookie Kudos.”

11 TheGreatest21Days.com, The Minor Leaguers of 1990, Vic Rodriguez, Something Special.

12 In October Rodriguez played in the Orioles’ 14-game tour of Japan.

13 Rodriguez was declared a minor-league free agent in November 1985 and after each of the following three seasons.

14 Also, Cal Ripken was the Orioles’ starting shortstop beginning in 1983. In 1982 he played shortstop and third base.

15 From 2004 to 2006 he was the team’s Latin field coordinator. His hitting instruction positions: 1996-98 Sarasota hitting coach; 1999 Gulf Coast League Red Sox hitting coach; 2000 Augusta hitting coach; 2001 Gulf Coast League Red Sox hitting coach; 2002 minor-league hitting coordinator; 2003 minor-league hitting instructor; 2007-12 minor-league hitting coordinator; 2013-17 major-league assistant hitting coach.

16 Christopher Smith, “Red Sox Coaching Staff Full of Awesome Stories,” Newburyport (Massachusetts) News, November 1, 2013,

https://newburyportnews.com/sports/red-sox-coaching-staff-full-of-awesome-stories/article_c9d6a46d-37b1-5732-9ea5-9604c154f420.html.

17 Jen McCaffrey, “How Red Sox Hitting Coach Chili Davis, Assistant Coach Victor Rodriguez Have Fostered Baseball’s Best Offense,” Mass Live, May 27, 2016.

https://masslive.com/redsox/2016/05/how_red_sox_hitting_coach_chil.html.

18 Roger Lalonde, “MLB: Red Sox Hitting Coach Victor Rodriguez Relishing World Series Crown,” Naples (Florida) Daily News, November 19, 2013, online.

19 McCaffrey.

20 McCaffrey.

21 September 2, 2014, at Yankee Stadium

22 McCaffrey.

23 Terry Francona email.

24 Peter Abraham, “The Art of Throwing Batting Practice – and How It Helps the Red Sox,” Boston Globe, March 18, 2017. https://www.bostonglobe.com/sports/redsox/2017/03/18/the-art-throwing-batting-practice-and-how-helps-red-sox/XvDihsoLVar6TeNyPgwfeI/story.html.

25 Abraham.

26 Abraham.

27 Orioles Roster and Staff, Baltimore Orioles Official Website; Victor Rodriguez biography.

Full Name

Victor Manuel Rodriguez

Born

July 14, 1961 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.