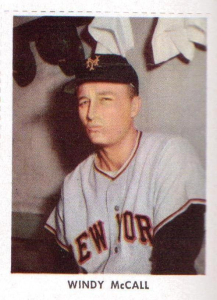

Windy McCall

John William “Windy” McCall grew up about three blocks from Holly Park in San Francisco. He’d bring a bat and a glove and hop in a neighborhood game. “If you didn’t get chosen, then you hung around until someone went home for lunch.” McCall played a year in American Legion ball and a year in high school. Born July 18, 1925, he grew up in the Mission District. He was 16 when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

John William “Windy” McCall grew up about three blocks from Holly Park in San Francisco. He’d bring a bat and a glove and hop in a neighborhood game. “If you didn’t get chosen, then you hung around until someone went home for lunch.” McCall played a year in American Legion ball and a year in high school. Born July 18, 1925, he grew up in the Mission District. He was 16 when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Mac’s father was a housebuilder and a remodeler, but his mother had her hands full with three children at home — two boys and one girl. John was the only one who played ball. “My brother didn’t want to get his hands dirty. He wound up as a pretty good high school teacher, in chemistry and physics.” His father, John Patrick (Jack) McCall, used to bring him around to weekend games in San Francisco. “I played for the San Francisco Seals Juniors when I was 17. We had about eight teams in San Francisco. I won the batting title in Legion ball when I was 17 with the Zane Irwin Post.” The Seals Juniors were a semipro team that played in Seals Stadium on Saturdays. “I got to play there, but not to pitch. I played the outfield. Because I was a hitter. That’s the way I started. Got an early graduate from high school, and I was six months, one season at USF when I joined the Marine Corps.”

Johnny McCall graduated from Balboa High School in January 1943 and had a scholarship to play center field for the University of San Francisco, but never pitched there. Nor did he pitch in high school, but he did catch the eye of Brooklyn Dodgers scout Charlie Wallgren. The left fielder for USF was future Red Sox teammate Neill Sheridan. Bill Renna, who played for Boston in 1958 and 1959, was the team’s right fielder. Later in 1943, after playing a little semipro ball in San Mateo, McCall signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers, as an outfielder, and was assigned to Olean but never reported. He said he never reported “because I am now a private in U.S. Marine Corps Reserve.” Just two weeks after signing — still just 17 years old — he had joined the Marine Corps. And he received a “nasty letter from Rickey” — Branch Rickey — who wrote that McCall should have requested permission. The armed services wanted ballplayers, as entertainment for the troops, and Rickey could have set it up for him through the Dodgers.

The new recruit joined the Fourth Division, assigned to the Pacific theater, and served in locations from Iwo Jima to Okinawa. Naturally, Private McCall played a little baseball in the service, a couple of games on Maui but mostly after he’d been given MP duty on Okinawa. “We got to play some. No one could throw hard enough, I guess. I had a good arm. I started pitching there.” McCall was a lefthander.

“We were floating reserve off of Iwo [Jima], but the third or fourth day, we had too many guys on Iwo — really, too many targets — so they changed our ship into a hospital ship and they didn’t break up our replacement battalion. They shipped us all back to Maui and Honolulu. They had to rebuild the 4th Division because of all the casualties. The company I joined only had seven men left. They broke us into battalions — replacement — and then we went by LST from Hawaii from Saipan/Tinian. Maneuvers again, and then we were going to go into Tokyo Bay when they dropped the atom bomb. So I wound up in Okinawa as an MP.

“We were cleaning up Okinawa because they still had Japanese living in caves and coming out at night and stealing food and things like that. The day I left Okinawa, the 16th of May, we had 12 that we got living in a cave. One was an officer and all the rest were in uniform. They had their rifles all ready. They gave up because they didn’t have any airplanes around. When the interpreter told them the war was over, they couldn’t believe it.”

McCall was reinstated in organized baseball on July 11, 1946, but didn’t play professionally that year. He did play some semipro ball in California, pitching some, and even played against [Jackie] Robinson’s All-Stars, a black barnstorming team, as they toured the West Coast. When he left the Marine Corps he was 21 years old. His parents had had to sign for him when he was 17, but now he was a free agent and could sign with whichever club he pleased. He chose to sign for the same scout, Charlie Wallgren, but Wallgren now was working for the Red Sox. “I got a bonus this time. I didn’t get a bonus from Brooklyn. I went to spring training in ’47.” It was a $6,000 bonus, half on signing and half at the end of the season. It was a good bonus for the era.

Assigned to Roanoke, a team in the Class B Piedmont League, McCall played under manager Pinky Higgins. “I pitched batting practice a couple of times and played in the outfield a couple of times. I asked him, ‘Hey, we’ve got a doubleheader next weekend. Lynchburg. I’d like to pitch the second game of the doubleheader.’ He said, ‘Fine. Pitch batting practice tomorrow and you can pitch on Sunday.’ So I did. And I won. And I won 17 games. We won the championship.” McCall was 17-9 with a 3.78 ERA, and won three more games in the playoffs. In 219 innings, he struck out 198 opponents and was named to the Piedmont League All-Star team.

His record at Roanoke earned him another visit to spring training, and this time he picked up his nickname — from Ted Williams. He’d explained the nickname to the United Press, “I guess they think I like to talk. Names don’t hurt much, though. Base hits hurt more.” Remembering Williams almost 60 years later, he said, “In 1948, we were in spring training and about the last week of the season, Ted gets two or three dozen baseball bats. He looks them over. This is after a game, and I happened to be there with Ellis Kinder. Ted would pick up the bats with the closeness of the grain, the little curlicues. I was kidding him about hitting, and he said, ‘These are my good bats.’ He picked out about eight or nine and he puts his number on them, #9. Johnny Orlando, the clubhouse guy, put a big ‘P’ on them. He said, ‘Have your choice. You can have any of those, but not mine.’ I picked out a couple. In the conversation, I told Ted, ‘You know, I’m pitching batting practice tomorrow. I’m scheduled. Are you going to hit against me?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Well, bring up your good bats.’ So I pitched batting practice to him. About a week later, we got to going north. I think we got to Knoxville, and somebody asked me, “Have you seen the Boston Globe?” I guess Ted had told this sportswriter that he knew about me, said, ‘The windy one told me when I was pitching batting practice to bring up some of my good bats.’”

“I told him, ‘I can hit, too.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’re not going to hit on this club.’ I said, ‘No, I know. I signed as a pitcher.’” Windy did hit .667 for the Red Sox in 1949, but finished his years in the majors with a .146 average.

McCall worked a better deal than Mickey McDermott on his contract. “Joe Cronin [the general manager] called me to the office. He waited till two days before the opening of the season and he calls me upstairs and he says, ‘Here’s your contract. You earned it.’ I said, ‘Good’ and I looked at it and I said, ‘No, I’m not going to sign this.’ I said, “Well, you’ve got $5,000’ — which was the minimum — ‘and then if I’m optioned, they’ve got $4,000.’ I said, ‘I want five across the board, whether I’m optioned or not. You said I made the team.’ So he said, ‘Well, I don’t know. I’ll think about it.’ When I hit the bottom of the stairs — his office was on the second floor — the secretary yelled at me, ‘Come on back. I think Joe wants to talk to you again.’ He put the five/five. So I went down and I told McDermott. He said, ‘I’m probably not going to make the team anyway.’ They offered him a contract, but it was a five/four. He signed it. The next day, he went to Scranton on option. I hung around for 20 or 30 days and then I went to Louisville.”

McCall pitched well in spring training. His last work was to throw the final four innings of a City Series game against Warren Spahn and the Boston Braves. Spahn won the game, 3-2, but all three runs had been the responsibility of fellow rookie southpaw McDermott. Windy’s major league debut came on April 25, 1948 — a starting assignment in Yankee Stadium. He didn’t last long, giving up a first-inning three-run homer to Joe DiMaggio. After McCall allowed six hits total, and a walk, Sox manager Joe McCarthy called on the bullpen and brought in Harry Dorish. “They were really Texas Leaguers, a couple of them. DiMaggio…. I shook off a curveball and Birdie Tebbetts called time. He says, ‘I want your curveball on 3 and 2. This guy’s a hitter.’ So I threw the curveball. I should have thrown a fastball. I did well against him in spring training.” The Red Sox lost the game, 5-4, with all four Red Sox runs coming in the top of the ninth. McCall was assigned the loss. And he was assigned to Louisville the very next day. He was recalled in September but saw no game action. All told, McCall spent about a month with the major league club.

Windy got some work in with the Colonels, though, pitching 183 innings with 149 strikeouts. He gave up 182 hits and ran up a 4.67 ERA, with a 9-12 record.

In 1949, McCall started the season with Boston, pitching in the City Series again, a couple of times against the Yankees, and let in just one run in five innings during a game with the Tigers that ended in a 14-14 tie after 13 innings. In mid-May, when the rosters had to be cut down, McCall departed to the minors, optioned to Seattle on May 19. Contractually, he was returned from Seattle on July 11, then assigned to Louisville four days later. With the Red Sox, he’d pitched 9 1/3 innings, and lowered his ERA from 20.25 to 11.57. He was 0-5 with Seattle in the Pacific Coast League and 5-2 with Louisville.

McCall wished he’d had a chance to play more for the Red Sox, and regrets both the lack of a pitching coach and Joe McCarthy’s shortcomings in dealing with pitchers. “I never really got to play for the Red Sox because of Joe McCarthy. I’m down there [during 1949 spring training] and I’m playing catch with Ellis Kinder — off the field, during batting practice — and he’s showing me his changeup. He had a hell of a changeup, Ellis did. And McCarthy saw us and he walks down…all the way down in the corner in right field, off the field, and he yells at Kinder, ‘Get your ass in right field and shag the flies.’ It’s batting practice. And, ‘Mac, I want to talk to you.’ We walked all the way down to home plate. Before we got about halfway, Joe says to me, ‘You know, with your fastball and curveball, you don’t need a changeup.’ Well, when he said that, it kind of sunk in that he didn’t know anything about pitching. And he didn’t. We never had a pitching coach in those years.

“Fireman Murphy. They made him farm director. [Right at the end of the 1949 season] he says, ‘I understand you told one of the guys you’d rather get traded because we don’t have a pitching coach.’ I said, ‘That’s right. You don’t.’ I says, ‘Trade me.’ So they did. They traded me to Pittsburgh.” It was a conditional deal; the Pirates could send him back at any time until the first 30 days of the regular season had expired.

In spring training for Pittsburgh, about two days before the season started, he got hit hard in the hand by a line drive that pretty much ended his major league aspirations for 1950. He got into two games, 6 2/3 innings in all, but he was black and blue all the way up the arm and the Pirates decided to send him down to Indianapolis. It was his third and final option, so the big league club didn’t call him back. He played all of 1951 for Indianapolis (10-9, 4.53) and started 1952 there as well, but was moved to Birmingham in the Southern Association fairly early in the year when the Red Sox bought his contract back on May 29. With Birmingham, McCall was 10-8, with a 4.89 ERA.

Before the season in 1953, he was purchased by the San Francisco Seals and got the chance to pitch in the ballpark he’d played in as a youth. For the Seals, despite seeing his season end with a broken finger in mid-August, McCall won 12 and lost 7 with his best earned run average ever: 3.04. In October the New York Giants made quite an offer for him, trading Frank Hiller, Adrian Zabala, Chuck Diering, and $60,000 cash to sign up Windy. Sportswriter Joe King mused that after a commitment like that, McCall “would have to stink to be cut loose.” King later dubbed McCall “the boy with the talented tonsils.”

In 1954, he started to get a chance to perform, pitching 61 innings in 33 games with four starts. He also earned his first major league win on August 22, pitching two innings in relief as the Giants came from behind in the bottom of the ninth to beat the Pirates, 5-4. His record was just 2-5, but he had a very good 3.25 ERA. Working under Leo Durocher again in 1955, McCall got six starts and threw four complete games. He was 6-5, with a 3.69 ERA, and more or less pitched about the same in 1956, a 3.61 ERA with a 3-4 record. He started with the Giants again in 1957, but after just three full innings of work was sent to the Seals again, and then to Miami in the International League. All of 1958 was with Miami, as was the start of ’59, though McCall spent most of the ’59 season with Seattle again, back in the Coast League. “I think I lost about three or four feet off my fastball. The Coast League was a pretty good league.”

After baseball, McCall worked for 25 years in sales for Bekins Van and Storage in San Francisco, almost exclusively commercial work, though he did help move Willie Mays at one point. Whenever Bekins had a call from a ballplayer, they gave the job over to McCall. In 1980, the McCalls moved to his wife’s home state of Arizona. There, Windy got into real estate, working as an agent for U.S. Home. The McCalls have a daughter and two sons. Sandy McCall might have had pro baseball potential, but he had a scholarship to Stanford and he really enjoyed golf. The golf coach at Stanford told him he’d ruin his golf swing if he played baseball, too, so he quit baseball. McCall’s other son was more of a swimmer.

Asked about his lifetime batting average of .146, Windy says, “It should have been a lot more. With the Giants, I didn’t really have a chance to hit. We had Dusty Rhodes, Bobby Hofman, Bill Taylor — all pinch-hitters. They all hit .300. And then we picked up Hoot Evers from Detroit on waivers, too, and he was quite a hitter.” But his thoughts returned right away to pitching: “It’s too bad we didn’t have a pitching coach with the Red Sox. We all could have used some guidance. We had a guy like Boo Ferriss. He had a sore arm, and [McCarthy] started him all the time. He should have started McDermott or McCall, but, you know….

“I always wondered if I’d stayed in baseball…. I know I could hit.”

Windy McCall died in Tucson, Arizona on February 5, 2015.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Interview with Windy McCall by Bill Nowlin on February 26, 2006

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

John William McCall

Born

July 18, 1925 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.