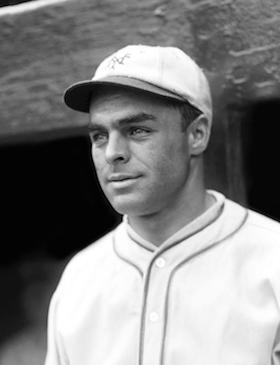

Doc Farrell

There were a couple of big families in Doc Farrell’s life. He was the eighth of 10 children, and had seven of his own. He enjoyed nine years in the big leagues, and seems to have had an affinity for two-team cities, playing for both New York teams, both Boston teams, and one each of the teams in Chicago and St. Louis. An infielder – mostly a middle infielder – Farrell played in 591 games, hit for a .260 average, and drove in 213 runs. He was not the best of fielders, however, with a .934 lifetime fielding percentage – and yet in 1932 Spalding offered an Eddie Farrell glove (for $7.50) for sale, on the same page of their catalog as one for Frankie Frisch.1

There were a couple of big families in Doc Farrell’s life. He was the eighth of 10 children, and had seven of his own. He enjoyed nine years in the big leagues, and seems to have had an affinity for two-team cities, playing for both New York teams, both Boston teams, and one each of the teams in Chicago and St. Louis. An infielder – mostly a middle infielder – Farrell played in 591 games, hit for a .260 average, and drove in 213 runs. He was not the best of fielders, however, with a .934 lifetime fielding percentage – and yet in 1932 Spalding offered an Eddie Farrell glove (for $7.50) for sale, on the same page of their catalog as one for Frankie Frisch.1

Farrell was a blacksmith’s son. It must have been challenging for Jerome Farrell and his wife Mary (Mary Ann Maley) to provide for 10 children, but that they did. She had two Irish parents, he an Irish father. Edward Stephen Farrell – later widely known as “Doc” because of his degree in dentistry, which he earned before playing professional baseball – was born on the day after Christmas, December 26, 1901, in Lestershire Village, Union Township, Broome, New York, near Binghamton. (In 1916 Lestershire Village became Johnson City.)

The 1910 census, when Edward was still 8, shows his oldest sibling Florence (21) working as a clerk in a dry goods store. Brother Walter was 19, working as a retail clerk in a drug store. Also helping bring money in to the family were brothers Howard (17), John (15), and Charles (13), all of whom were working as newsboys selling papers on the street. Anna and Ethel followed in succession, then Edward, with James and Loretta born later.

Edward went to the Johnson City schools, graduating from Johnson City High School, and then the University of Pennsylvania where he received his DDS degree in dentistry. When he played baseball, he was listed at 5-foot-8 (he said he was an inch taller) and 160 pounds.2

He’d been captain of the football team in high school and played shortstop, but as pointed out in a Binghamton newspaper many years later, “in a high school that had only six boys in his graduating class (1919), the squad was strictly self-propelled and un-uniformed.”3

It was at Penn that he became more active in team sports; he earned team letters both as a halfback on the football team and as a shortstop in baseball. He was captain of the baseball team his senior undergraduate year.4 The Dodgers made him an offer but “wiser heads, Pat Kelly’s for one, prevailed,” Farrell said.5

John McGraw of the Giants didn’t want to wait until Farrell graduated to sign him, so he engaged in a bit of subterfuge. He’d spotted Farrell in 1923 and saw to it that he played for a summer team in Glens Falls, New York, managed by former Giants second baseman Larry Doyle. McGraw got a favorable report and signed Farrell “undercover shortly after: a $2,500 bonus which was very fattening for those days, and $100 a month ‘laundry money,’ the next year $300 per month.”6 An unidentified obituary in Farrell’s Hall of Fame player file said he had “joined the Giants in 1924, the year before his graduation, but did not sign because he wanted to retain his eligibility for college baseball.”7

He’d been spotted as early as 1921 by Ed Walsh, who was running a semipro team in Oneonta. In 1922, he played for the team again, under the aegis of Al Bridwell, and then in 1923 “signed an agreement with the Giants to join the team as soon as he had graduated from college.”8 McGraw invited him to make one road trip with the Giants in 1924 as a “guest” of the ball club, and talked him out of playing football in his final year at Penn.9

Farrell didn’t go through any seasoning in the minor leagues. In fact, his June 15, 1925, debut with the Giants was three days prior to his graduation from dental school. He was on the road when the degrees were distributed. That first game was in Pittsburgh, Farrell playing third base, subbing for Heinie Groh. He was 0-for-3. He scored his first run on the 16th, collected his first base hit on the 18th, and drove in his first run on the 19th, in a 5-4 win over the Reds in Cincinnati that ended in a hail of pop bottles when the umpire called interference on a Reds baserunner for the third out in the bottom of the ninth.

He didn’t hit that well his first season, batting .214. There were only four RBIs and three of those came in games where Phillies pitchers were clearly struggling, two in the 24-9 Giants win on September 2 and one in their 14-10 win on the 5th.10

In 1926, Farrell got more work and hit better, too, playing in 67 games, mostly at shortstop, batting .287 with 23 RBIs. He seemed to victimize Brooklyn with his runs batted in. On May 25, in the first game, he drove in four runs in a 5-1 home win at the Polo Grounds. His double in the bottom of the ninth beat Brooklyn in a 1-0 game on June 5. In the first game on September 11, his three RBIs made all the difference in another home win against Brooklyn, 5-3. Eight of his 23 RBIs were against Brooklyn.

Farrell’s best year was 1927. He began the season with the Giants, playing shortstop on a regular basis thanks to Travis Jackson’s April 1 appendectomy in Memphis. He got off to a spectacular start. Five weeks into the season, the New York Times said he was “about the main reason why the Giants are leading the league.”11 Through the May 22 game, he was batting a league-leading .408 – and then McGraw benched him. Travis Jackson was back. Richards Vidmer, writing in the Times, dubbed it “something of a shock.” He acknowledged that some felt Farrell was hitting a little bit over his head. He knew that Farrell lacked experience, and thus was a little slow, in turning the double play. But he didn’t think they could afford to lose his bat and expected the team would install Farrell at third base.12 That’s what happened.

There was another shock just a couple of weeks later. The Giants and the Boston Braves executed a trade on June 12, one the Giants thought might make them stronger at pitcher and catcher. They acquired Larry Benton, Zach Taylor, and Herb Thomas, in exchange for Kent Greenfield, Hugh McQuillan, and Farrell. There had been rumors a trade was in the offing, but “no one thought McGraw would let go of Eddie Farrell.”13

Perhaps McGraw felt that Farrell was indeed over-performing and he was able to move him when he was at his highest value. He played very well for the Braves, appearing in 110 games with a .292 batting average and driving in 58 runs. (He even played in an exhibition game in hometown Binghamton on July 24.) He ended the year with a combined average of .316 and a total of 92 RBIs. Farrell fell off dramatically in 1928. He drove in fewer than half as many runs (43) and hit .215. The Braves finished in seventh place both years.

The team signed Rabbit Maranville for 1929 and he and Farrell battled it out to start at shortstop. During the springtime, first Maranville seemed to have the upper hand, and then Farrell, but when it came time to start the season, Maranville got the nod. Farrell, in fact, only started one game, appearing in four others. On June 14, the Giants brought him back to New York, trading outfielder Jimmy Welsh. The Giants had a short-term need at second base due to injuries but took full advantage of Farrell’s abilities as a utility infielder for the rest of the season. He appeared in 63 games, though only hit .210 overall on the year, with 18 RBIs. He’d been beaned by Dazzy Vance on March 31 and knocked unconscious. At least one account concluded “he proved a little gun shy at the plate.”14

In October 1929, Farrell married Helen Lynch.

Farrell was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, with outfielder George “Showboat” Fisher. for outfielder Wally Roettger just before the 1930 season opened, on April 10. It was more of the same for him with the Cardinals, batting .213 in 23 games. The magic he’d had in 1927 was seemingly gone. Near the end of June, he was placed on waivers. On June 24, he was claimed by the Chicago Cubs.15 With Rogers Hornsby hurt, they needed another infielder. He had a bit of a rebirth, batting .292 in 46 games. The Cubs were in the pennant race until right at the end of the season, losing to St. Louis by two games.

Rogers Hornsby took over from Joe McCarthy as manager for the Cubs at the very end of the season, winning the last four games. In November he made a move to bring in pitcher Ed Baecht, who’d been 26-12 for the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels. He wanted him so badly he sent seven players, including Farrell, to the Angels to get him.

For the first time in his career, Eddie Farrell was a minor leaguer. He had a good year in 1931, batting .327 in 185 games (the Coast League had a very long schedule.) He’d almost sat out the year, dissatisfied with being asked to play for a smaller sum than he’d become accustomed to. And he did have dentistry to fall back upon. Matters were worked out, and – as it happened – his good work got him back in the big leagues. The New York Yankees made a deal at the recommendation of scout Bill Essick, giving Los Angeles their choice of $15,000 or two players.16 The New York Times cited manager Joe McCarthy: “Farrell, who was sent by the Cubs to Los Angeles after Rogers Hornsby replaced Joe McCarthy at Chicago, was brought back to the major leagues by McCarthy as soon as Joe became the Yankee pilot.”17

Farrell spent the next two years with the Yankees, working as a utility infielder both seasons. He appeared in 26 games, 16 of them in September, batting .175. In 1933, he worked in 44 games, with a much better .269. He had four RBIs in ’32 and six RBIs in ’33.

On January 11, 1934, Farrell was released outright to the Newark Bears. Injured early in the year, he was able to appear in 88 games, hitting seven homers, batting .233.

He was one of four players sent to the San Francisco Seals in exchange for outfielder Joe DiMaggio, but he did not report. And then the Yankees decided they didn’t want DiMaggio.18

In the spring of 1935, Farrell was on the roster of the Syracuse Chiefs.

Near the end of March 1935, Red Sox shortstop Joe Cronin hurt his wrist and the Sox had to seek out a replacement. They acquired Farrell, and slotted him into action right away.19 Farrell, now with his second Boston team, played second base in four games, from April 25 through May 1. He doubled and drove in a run on the 25th and singled the next day, but he only had seven at-bats on the two days. That left him hitting .286; his two later appearances were for defensive purposes. The four games were his final four in the major leagues.

The Red Sox cut ties with him. Farrell considered an offer to manage the Elmira club in the New York/Penn League, but he decided instead to return to his dental practice in Newark.20 Later in the 1935 season, Farrell played second base for Newark again in 17 games, batting .405. It was a nice way to end his career.

Farrell based himself in Newark before he finished baseball, and maintained his practice there over the decades. He became head of the department of dentistry at St. Michael’s Hospital in Newark, and a consultant at St. Clair’s Hospital in Denville. His love of baseball never faded. He did play some semipro ball, including for the Springfield Greys in metropolitan New York in 1937. In later years he timed his vacations to take in games at spring training.

Farrell died of lung cancer six says shy of his 65th birthday, on December 20, 1966, at St. Barnabas Hospital in Livingston, New Jersey. He and Helen had five daughters and two sons, both of whom graduated from the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. Son Edward R. Farrell served on swift boats in Vietnam and spent two years recovering at St. Albans Naval Hospital from leg injuries; Lt. Farrell died of cancer at age 35. Richard S. Farrell became a fighter squadron commander in the Navy, later working as a pilot for Federal Express.

Interestingly, Doc Farrell’s son-in-law George Feeney was an uncle through marriage to the pitcher Jim Lonborg, through Jim’s wife, Rosemary Feeney Lonborg.

In the year 2000, Eddie Farrell was inducted into the Binghamton Baseball Shrine.21

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Farrell’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Doc Farrell’s granddaughter, Carol Russell, for some Farrell family details.

Notes

1 Spalding catalog January 5, 1932, page 20.

2 Farrell reported he was 5′ 9″ tall on his Hall of Fame player questionnaire.

3 John Fox, Binghamton Sunday Press, June 28, 1964: 2D.

4 “Dr. Eddie Farrell Dead at 64; Dentist Played Ball in Majors,” New York Times, December 22, 1966.

5 John Fox.

6 Ibid.

7 Unidentified obituary, January 7, 1967, Farrell player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

8 Irvin M. Howe, “Hot Stove League,” unidentified newspaper clipping in Farrell’s Hall of Fame player file. The column ran, without Howe’s byline, in the Cleveland Plain Dealer of February 25, 1926: 17.

9 Ibid.

10 New York Times, December 22, 1966.

11 “Farrell is Physician to Giants’ Infield,” New York Times, May 22, 1927: S5.

12 Richards Vidmer, “Farrell Benches in Giant Shakeup,” New York Times, May 24, 1927: 28. Farrell had suffered a bit of an injury to his knee at the time, it came out later.

13 “Farrell Is Traded; Giants Get Benton,” New York Times, June 13, 1927: 24.

14 Unidentified obituary, January 7, 1967.

15 “Cubs Purchase Eddie Farrell from Cards,” Chicago Tribune, June 24, 1930: 21.

16 “Farrell Sold to Yankees,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1931: A15.

17 “Two Released by Yankees,” New York Times, January 12, 1934: 33.

18 “Yanks Not To Claim DiMaggio,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1935: A13. DiMaggio played 1935 with the Seals and hit for a .398 average; DiMaggio began his major-league career in 1936.

19 Gerry Moore, “Cronin’s Wrist Is Painfully Hurt,” Boston Globe, March 31, 1935: A24.

20 “Rolfe Receives A Silver Service,” Boston Globe, June 10, 1935: 9.

21 “Ex-Yankees Star Among Binghamton Shrine Honorees,” Binghamton Press & Sun Bulletin, June 25, 2000: 5B. The “star” in the headline was Bobby Richardson.

Full Name

Edward Stephen Farrell

Born

December 26, 1901 at Johnson City, NY (USA)

Died

December 20, 1966 at Livingston, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.