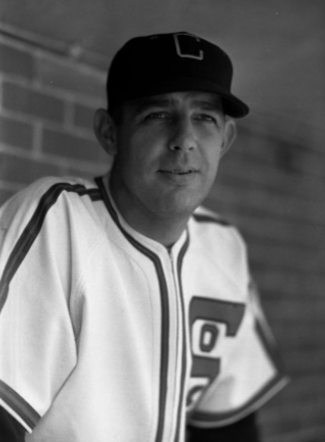

Thornton Lee

When the Chicago White Sox acquired him before the 1937 season, Thornton Lee was a hard-throwing but wild 30-year-old southpaw with just 12 victories in three-plus seasons for Cleveland. But under the aegis of manager Jimmy Dykes and coach Muddy Ruel, Lee developed into one of the best left-handers in the big leagues and the anchor of the White Sox pitching staff on weak-hitting teams from 1937 to 1941. Averaging 15 wins and 243 innings per year during that stretch, Lee enjoyed one of the best years in franchise history in 1941, completing 30 of 34 starts and winning 22 games.

Thornton Starr Lee was born on September 13, 1906, in Sonoma, California, north of San Francisco. Thornton derived his middle name from his father, Starr Lee, a farmer and employee of the Southern Pacific Railroad. His mother, Celia Lenice (Steinhoff) Lee, was a homemaker who raised four children (Laura, Thelma, Thornton, and Willard) born in the first decade of the 20th century. By 1909 the Lees had moved to Willcox, Arizona, a stop on the Southern Pacific Railroad east of Tucson, to try their luck as homesteaders. Finding it difficult to eke out an existence in the brutal climate, the Lees returned to California and settled in Oceano in San Luis Obispo County, about 190 miles northwest of Los Angeles.1 A bright and athletic youngster, Thornton attended Arroyo Grande High School and upon graduation in 1925 entered California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo intending to become a teacher or coach.

Big for his day, about 6-feet-3 and 180 pounds in college (though he got bigger as a professional ballplayer), Thornton was a legendary athlete at Cal Poly. He was a track star who competed in the javelin, discus, and shot put; a center on the basketball team; and an end on the football team. But his passion was baseball. The lithe left-hander was a hard thrower who once struck out 19 batters in a game against San Jose State and began attracting professional scouts during his sophomore year.2 Denny Long, a scout for the Chicago White Sox, offered him a contract, but was spurned by Lee, who wanted to get his degree.3 In 1928 he was signed by Dan Sheehe, a scout for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.4

Lee progressed slowly and methodically through the minor leagues for six years, flashing signs of brilliance tempered with inconsistency and bouts of wildness. Lee’s first assignment was with the Salt Lake City Bees in the Class C Utah-Idaho League. He roomed with another promising left-hander, Vernon “Lefty” Gomez.5 Finding a chance to pitch for the eventual league champs in a short season proved difficult. Lee won one of four decisions and posted a 6.51 ERA in 37⅓ innings. Dropped to Class D for the 1929 season, Lee was able to pitch regularly for the Globe Bears (who actually played their games in Miami, Arizona), evenly splitting his 22 decisions, but leading the league in walks (118) and posting a 5.71 ERA. When the Seals did not exercise their option on the young hurler, the Tampa Smokers of the Class B Southeastern League drafted Lee on umpire George Blackburne’s recommendation.6

Lee enjoyed a breakout season in Tampa, where he developed a reputation as a strikeout artist, whiffing a league-record 14 batters in one game and tossing a no-hitter in another.7 Acting on the advice of scout Bill Rapp, the Cleveland Indians purchased the hot prospect for a reported $10,000, although his tantalizing potential (a league-high 145 strikeouts) was matched by his control problems.8 The Indians assigned Lee to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Class A Southern Association, where he struggled for the remainder of the 1930 season.

Following his first taste of the big leagues at the Indians’ spring training in 1931, Lee was optioned to the Shreveport Sports of the Class A Texas League, where his record (7-14) was more an indicator of his poor team (66-94) than of his ability. Lee was promoted to the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association in 1932, but his “arm went lame” after he had logged just 38 innings.9 After resting for several weeks, he was dropped two classifications to the Class B Wilkes-Barre Barons of the New York-Penn League. There he won 14 games despite pitching in pain all season. Back with the Mud Hens in 1933, Lee proved that he was major-league-ready by harnessing his speed and winning 13 games.

Six days after his 27th birthday, Lee made his major-league debut for the Cleveland Indians on September 19, 1933. In relief of starter Clint Brown, Lee struck out the only batter he faced in a 4-3 loss to the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. Five days later, in his first start, he tossed a complete game to defeat the Chicago White Sox, 12-6, despite issuing a career-high nine walks. Lee “looked the part of a top-notcher” in his late-season trial, wrote The Sporting News.10

Lee was groomed for three years (1934-1936) as the Indians’ much-needed left-handed starter but had trouble finding consistent opportunities to demonstrate his ability. He logged just 85⅔ innings as primarily a long reliever in 1934 for manager Walter Johnson, whose confidence was notoriously difficult to earn. Indians beat reporter Gordon Cobbledick wrote that baseball sage Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics encouraged the Indians to keep pitching the young left-hander despite his control problems, reminding them that left-handers develop more slowly than right-handers.11

By Lee’s third full season with the Indians (1936), he had been described as a “ ‘comer’ for so long that he seems something of a veteran.”14 Manager O’Neill became exasperated by the lefty’s lack of control and banished him to the bullpen for much of the season. Lee pitched in a career-high 43 games, but started just eight times and finished with only three wins in eight decisions. At the baseball winter meetings, Lee was sent to the Chicago White Sox as part of a three-team trade involving the Washington Senators (who shipped pitcher Earl Whitehill to the Cleveland Indians) and the White Sox (who dealt pitcher Jack Salveson to the Senators).

Considering his pedestrian 12-17 record in just over three big-league seasons, expectations were minimal for the 30-year-old Lee in 1937, but he landed in an ideal situation, with manager Jimmy Dykes and coach Muddy Ruel both known for their reclamation projects. Lee’s former manager O’Neill looked like a genius when the Indians clobbered the left-hander in his first start with the White Sox.15 Undeterred, Dykes sent Lee to the mound against the predominantly left-handed-hitting Yankee lineup four times in his first six starts. He was victorious each time. The third of Lee’s four victories over the Yankees (a complete game on June 8) pushed the upstart White Sox into a tie for first place, the first time the club had been in first place so late in the season since 1920. Dykes employed six regular starters and continued using Lee against clubs that relied on left-handed power (18 of 25 starts came against New York, Cleveland, and Washington). In a four-game span in July, Lee tossed back-to-back ten-inning complete games to defeat the Senators and the Yankees (his fifth consecutive triumph over the club) followed by a five-hit shutout against the Senators. “One must have control and confidence in himself,” said Lee after the season. “A big fellow like me needs more work. Manager Dykes instilled the confidence.”16 Lee concluded the season with a resounding 11-inning shutout over the St. Louis Browns to finish with a 12-10 record and a 3.52 ERA (sixth best in the league).

It was the best season for the White Sox since 1920, and evoked hopes and dreams for an even better campaign in 1938, but instead the team dropped to sixth place. In an oft-repeated refrain throughout Lee’s most productive years with the White Sox, his record (13-12) did not reflect how well he pitched. The “tall southpaw [was] held largely responsible for the quaint notion that the New York Yankees couldn’t hit left-handed pitching,” wrote an Associated Press correspondent in light of Lee’s 1.61 ERA against the champions.17 The big lefty, an able-bodied hitter throughout his career with a respectable .200 average (167-for-835), belted all four of his career home runs, including two against the Yankees, in 1938.

Lee was one of the biggest pitchers in his era and was affectionately known as Goon or Goon-man for his enormous size and physical strength. “When I was with the Indians,” he said, “I weighed about 190 pounds. Now I am over the 220-pound mark. After I quit smoking I couldn’t keep my head out of the icebox. The extra weight gave me more stamina and increased my speed.”18 Lee was the staff workhorse in 1939, tying for the team lead with 15 victories and leading the club in innings (235). Noting the “paucity of left-handed talent” in the big leagues, The Sporting News wrote, “In probably no year since the American League came into existence at the turn of the century have the left-handed pitchers of the two majors been as mediocre a lot as this season,” and counted Lee, along with Lefty Gomez and the aged Lefty Grove among the exceptions.19

Lee’s success rested with a blazing, sinking fastball, a sharp-breaking overhand curveball, and his control. Syndicated sportswriter Harry Grayson wrote, “[Lee] did little more than rear back and pump the pill in there” as a member of the Indians, but Muddy Ruel transformed him into one of game’s best left-handers.20 “Ruel took me in hand and cured my wildness,” said Lee. “He picked out flaws in my delivery and pretty soon I had better than average control.”21 Over the course of several years, Ruel instructed Lee to shorten his long stride in order to stay on top of the ball and help his curveball break more sharply. On top of that was his unflappable mound presence. “Lee has one quality which great pitchers must have,” said teammate Ted Lyons. “He’s the coolest pitcher in baseball when under fire. Load the bases, get a count of three balls on the batter, and the Goon is like cucumbers on ice.”22

Lee’s commanding four-hit complete game against the Cleveland Indians in his first start of the 1940 season inaugurated a dominating two-year stretch during which he completed 54 of 61 starts. The White Sox finished in fourth place again in ’40, and Lee finished with a losing record (12-13), primarily due to poor run support. His 24 complete games trailed only Bob Feller’s 31. What might he have done had he started more than 27 times? Dykes continued to juggle his six primary starting pitchers so that Lee could face the left-handed sluggers on the Indians and Yankees (15 of his 27 starts were against them).

In 1941 Lee had one of the best years any White Sox pitcher has experienced in the lively-ball era. On a team that ranked last in runs scored, Lee posted a career-high 22 wins, led the American League with a 2.37 ERA, topped the major leagues with30 complete games (in a career-high 34 starts), and logged 300⅓ innings. Through much of May and into June, the White Sox pitchers kept the team in second place as close as a half-game out. “[Lee’s been] carrying Dykes’ hitless hitters on his back all season,” wrote The Sporting News.23 Often a tough-luck loser, Lee was locked in a scoreless duel with Red Ruffing of the New York Yankees through ten innings in the Bronx on July 13. In the top of the 11th inning, Lee surrendered a run to lose, 1-0. In Lee’s 11 losses, the White Sox scored just 27 runs combined and were shut out four times. “I’ve had the misfortune to stack up against pitchers on their good days,” said Lee.24 Often pitching on short rest during the final seven weeks of the season, Lee finished in a flurry, winning ten of 13 decisions. For the only time in his career, he was named to the American League All-Star team. In Briggs Stadium in Detroit, he pitched the fourth through sixth innings, surrendering four hits and a run in the junior circuit’s exciting 7-5 victory, which came courtesy of Ted Williams’s dramatic walk-off three-run home run.

Widely regarded as the best left-handed pitcher in baseball in 1941, Lee saw his career come crashing down as a series of injuries limited him to just ten victories and 41 starts over the next three seasons. He was sidelined with “torn shoulder ligaments” until July 5 in 1942;25 shoulder and back pain plagued him through the remainder of the season, limiting him to just eight starts and a 2-6 record. Forced to sign a “$1-a-year”26 contract for 1943 with the option of earning a full-fledged backdated contract, Lee suffered an additional setback when he was diagnosed in early May with three bone chips and a growth in his left elbow, which cast doubts on his future. He opted against potentially season-ending surgery in order to concentrate on his still aching shoulder. He underwent treatment involving a “gallows-like neck-pulling gadget” that supposedly stretched his shoulder and broke the adhesions.27 Lee’s return (he won four of five decisions over a five-week stretch from late May to July) created optimism and earned him a full contract; however, he struggled thereafter and finished with a 5-9 record.

After the season Lee underwent two operations to revive his career. In one he had bone chips removed from his elbow; the other operation involved severing a tendon in his neck that affected his shoulder. “It seems like the tendon becomes taut with age,” Lee said. “In some way [it] shut off the flow of blood to my arm when I raised it above my shoulder. This explains why I was good for just a few innings last year. … By the fifth inning or so my fingers would start getting numb. A lot of the times I couldn’t even tell if I had the ball in my hands.”28

The 37-year-old Lee returned in 1944 as a once-a-week pitcher, but the only breaks he encountered were bad ones. In his second start of the year, he tossed a career-best 12 innings in a 2-0 loss to the Tigers. In a relief appearance against the Philadelphia Athletics on July 9, Lee was hit on the lower arm near the wrist by a screeching liner from Bobby Estalella; Lee picked up the ball and threw Estalella out, but the damage was done. Lee had suffered a broken forearm.29 He was expected to miss the rest of the season, but returned to hurl two complete-game victories in September, finishing the season on a positive note and providing a glimmer of hope for 1945 despite his 3-9 record.

After three years of frustrating injuries, Lee made a remarkable comeback in 1945, going 15-12, completing 19 of 28 stars and posting the AL’s fifth lowest ERA (2.44). He made his first and only Opening Day start that season, earning the victory against the Indians, 5-2, and pitched consistently all season against competition that was admittedly depleted due to the war. On June 12 at Comiskey Park, he hurled arguably the best game of his career, an overpowering three-hitter against the Indians with a career-high 13 strikeouts. Though the sixth-place White Sox surprisingly led the AL in batting average for the first time since 1919, their bats were often silent in Lee’s losses; they scored two or fewer runs in ten of his 12 defeats.

The excitement resonating from Lee’s comeback dissipated soon after the start of his 14th season in the big leagues. Lee fought through early-season elbow pain, but ultimately succumbed to bone chips after just his seventh start of the season, on June 16. He was placed on the voluntary retired list, returned to Phoenix for rest and treatment and eventually had elbow surgery.30 Lee made an auspicious return in 1947, shutting out the St. Louis Browns on two hits and hurling a complete-game victory over the Yankees in his first two starts. His success proved illusory, though, and he would win just one more start that season, his final one in Chicago. At the age of 40 and with a long history of arm woes, Lee was relegated to the role of spot starter and reliever.

The White Sox released Lee after the 1947 season. In April 1948 he signed with the New York Giants, but his big-league career came to its conclusion when the Giants let him go on June 19. In 16 seasons in the major leagues, Lee’s record stood at 117-124; he posted an impressive 3.56 ERA in 2,331⅓ innings.

Lee had a short, unsuccessful stint with the Oakland Oaks before retiring to Phoenix. Since the mid-1930s he and his wife, Esther Mae Ellis (whom he met while playing in Miami, Arizona, and married in 1929), had called the desert their home. They had one son, Don, a right-handed pitcher who won 40 games in a nine-year big-league career from 1957 to 1966. Ted Williams homered off both Thornton (in 1939) and Don (in 1960), making him the only player to hit a round-tripper off a father and son. Thornton was lured out of retirement in 1949 by the Phoenix Senators of the Class C Arizona-Texas League, for whom he made 11 appearances. He went on to manage the Globe-Miami Browns in that league in 1950. Lee then had a prosperous career for more than 25 years as a businessman, most notably with Phoenix-based Garrett AiResearch, a producer of turboprop engines. He was inducted into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame in 1960 and the Cal Poly Sports Hall of Fame in 1988.31

The big left-hander never lost his passion for baseball. For almost four decades, he served as a part-time scout for a number of teams, including the St. Louis Cardinals, Washington Senators, and San Francisco Giants, retiring when he was 80 years old. An active outdoorsman, Lee maintained his stout physique his entire life. At the age of 90, Thornton Lee died from complications related to Parkinson’s disease.32 At the request of the family, no services were held.33

Sources

Websites

Ancestry.com

BaseballAlmanac.com

BaseballCube.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

SABR.org

Newspapers

Arizona Republic (Phoenix)

Chicago Daily Tribune

Cleveland Plain Dealer

New York Times

The Sporting News

Other

Thornton Lee player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Thornton Starr Lee obituary. Arizona Republic, June 11, 1997.

2 Cal Poly Mustangs. gopoly.com/inside_athletics/hof/Lee_Thornton.

3 Henry P. Edwards, press release, American League Service Bureau, released on December 19, 1937. Appeared syndicated as “Thornton Lee Took Years to ‘Get Right.’ Now He’s Chisox Star,” San Antonio Light, December 19, 1937, 18.

4 Press release, American League Service Bureau, released in 1937, in Lee’s Hall of Fame file.

5 Veronica Gomez and Lawrence Goldstone, Lefty: An American Odyssey (New York: Ballantine Books, 2013), 220.

6 Thornton Lee, American League press release, 1937, in Lee’s Hall of Fame file.

7 Ed Bang, “Thornton Lee Looms Up Like Good Prospect,” Cleveland News, January 30, 1931.

8 Henry P. Edwards, “Thornton Lee Took Years to ‘Get Right.’ Now He’s Chisox Star,” San Antonio Light, December 19, 1937, 18.

9 Billy Evans, “Building the Indians. Is This Lee’s Year?” February 10, 1936. (Unknown source, in Lee’s Hall of Fame file).

10 The Sporting News, October 5, 1933, 1.

11 Gordon Cobbledick, “Mack Advises Evans To Keep Lee on Roster,” Cleveland Plain-Dealer, September 16, 1934. Player’s Hall of Fame file.

12 Gordon Cobbledick, “Lee Displays Fastest Ball in Tribe Camp. Cleveland Plain-Dealer, no date. (in Lee’s Hall of Fame file).

13 The Sporting News, August 28, 1935, 1.

14 Ibid.

15 Irving Vaughan, “‘My Lefty Lee’ is Prof. Dykes Latest Sox Hit,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 5, 1937, 29.

16 Henry P. Edwards, “Thornton Lee Took Years to ‘Get Right.’ Now He’s Chisox Star,” San Antonio Light, December 19, 1937, 18.

17 Associated Press, “White Sox Again Trounce Cubs to Take Series Lead,” Sarasota (Florida) Herald, October 9, 1937, 6.

18 Eugene J. Whitney, “Bust With Tribe, Lee Travels on 20-Victory Road.” (Unknown source, in Lee’s Hall of Fame file).

19 The Sporting News, August 24, 1939, 4.

20 Harry Grayson, News Enterprise Association, “Ruel Rebuilds Chisox Hurlers With Instructions in Delivery,” Arizona Republic, June 9, 1941, II, 2.

21 Eugene J. Whitney, “Bust With Tribe, Lee Travels on 20-Victory Road.”

22 The Sporting News, April 2, 1947, 5.

23 The Sporting News, July 10, 1941, 14.

24 Eugene J. Whitney, “Bust With Tribe, Lee Travels on 20-Victory Road,”

25 “Thornton Lee Ready to Join Sox in St. Louis,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 8, 1942, 25.

26 The Sporting News, May 13, 1942, 10.

27 The Sporting News, June 24, 1943, 14.

28 “Lee, of White Sox, OK After Slit Throat.” (Unknown source, in Lee’s Hall of Fame file).

29 Edward Burns, “Dietrich Whips A’s, 4-3; Grove Defeated, 8-2,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1944, 17.

30 The Sporting News, August 7, 1846, 9.

31 Phoenix Regional Sports Commission, phoenixsports.org/hall-of-fame/history-of-the-hall-of-fame/; Cal Poly Mustangs, gopoly.com/inside_athletics/hof/Lee_Thornton.

32 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 232.

33 Thornton Starr Lee obituary, Arizona Republic, June 11, 1997 (in Lee’s Hall of Fame file).

Full Name

Thornton Starr Lee

Born

September 13, 1906 at Sonoma, CA (USA)

Died

June 9, 1997 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.