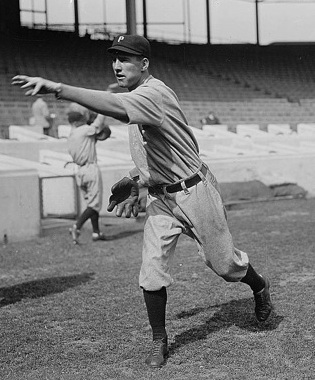

Ad Brennan

During the summer of 1913, a left-handed pitcher from the Philadelphia Phillies named Addison Brennan gained notoriety and a place in baseball lore when he was fined $100 and suspended for five days for punching New York Giants manager John McGraw after a game in Philadelphia. During the seventh inning of the contest between the Giants and the first-place Phillies on June 30, McGraw mercilessly berated the Philadelphia bench players from his third-base coaching position as the visitors pulled ahead with a four-run outburst. Ad Brennan had somewhat of an irascible reputation himself and responded in kind to the bully from New York. McGraw then began to focus his attacks on Brennan. The editor of Sporting Life declared that Brennan was “abused in alleged unprintable language and stigmatized as yellow!”

During the summer of 1913, a left-handed pitcher from the Philadelphia Phillies named Addison Brennan gained notoriety and a place in baseball lore when he was fined $100 and suspended for five days for punching New York Giants manager John McGraw after a game in Philadelphia. During the seventh inning of the contest between the Giants and the first-place Phillies on June 30, McGraw mercilessly berated the Philadelphia bench players from his third-base coaching position as the visitors pulled ahead with a four-run outburst. Ad Brennan had somewhat of an irascible reputation himself and responded in kind to the bully from New York. McGraw then began to focus his attacks on Brennan. The editor of Sporting Life declared that Brennan was “abused in alleged unprintable language and stigmatized as yellow!”

After the Giants’ victory, players of both teams walked toward the center-field clubhouse amid a large number of fans who had wandered onto the field. McGraw sought out the Phillies’ Mickey Doolan, whom he hoped to recruit for his world baseball tour that offseason. When he spotted Brennan ahead of him, McGraw reportedly pointed a finger at pitcher Brennan and proclaimed in words to the effect “There’s the fellow I’m going to get!”

McGraw had intimidated young players in the past, but he made a mistake in taunting Brennan. The 5-foot-11 pitcher turned and caught the approaching Giants manager with a left fist followed by a right. Both punches connected and the shorter McGraw went down, bleeding from his chin and cheek. As the Phillies quickly ushered Ad from the scene, a dazed McGraw was helped to the clubhouse. There were almost as many different versions of the affair as there were newspapers in the country. Unfounded reports, mostly in New York newspapers, said the Giants’ manager had been hit from behind and was deliberately kicked while on the ground.1

McGraw, back on the coaching lines the next day, maintained that he had been assaulted from behind and did not see who hit him. Ad, for his part, said he was exasperated by the taunts and believed he was going to be attacked. He said he regretted the incident but felt he did what anyone else would have done in the same circumstance. In the end Brennan became known as the player who got the best of McGraw and is forgotten as a fine major-league pitcher.

Addison Foster Brennan was born in LaHarpe, Kansas, on July 18, 1887, the third child and second son of John and Rosa Brennan. The grandson of an Irish immigrant who arrived in Philadelphia around 1810, John Brennan was a day laborer who went from job to job in small southeastern Kansas towns.2

Baseball was not young Addison Brennan’s first sport. According to a retrospective penned by the Kansas City Star’s Paul O’Boynick, he played football in high school and got his start in baseball as a 19-year-old substitute right fielder when only eight players showed up for a game. Within a few months he was playing the game for money. He began his professional career as a $40-a-month first baseman with Iola (Kansas) of the Oklahoma-Kansas League in 1907. When the team suffered a shortage of pitchers, Brennan volunteered to fill in. He did well enough to become a regular on the mound and gained recognition when he struck out 15 batters in a game. The Springfield (Missouri) Midgets of the Western Association especially took notice of his talent.3

Brennan won eight of 16 pitching decisions and batted .273 with the Midgets in 1908. On June 7 he struck out 13 Muskogee batters. After the Western Association season, his contract was purchased by George Tebeau, owner of Kansas City Blues of the American Association. However, Brennan never played for the Blues. Tebeau felt he had a surplus of pitchers so just before the 1909 season he sold Brennan for $300 to Wichita of the Class A Western League. On his way to an 18-victory season with the Jobbers, Brennan began to attract the notice of major-league scouts. That July Cincinnati Reds scout Tommy McCarthy purchased Brennan’s services for delivery after the Western League season. The price for the lefty was reportedly $3,500. With Wichita Brennan had a record of 18-16 and batted .252 in 51 games.4

As it turned out, the Reds acquired the rights to Brennan without having seen him pitch. Former major leaguer Monte Cross, a Philadelphia native, had seen Brennan pitch in Kansas and recommended that the Phillies acquire him. On January 10, 1910, a trade with the Reds brought Brennan to the Phillies in a deal that included pitcher Harry Coveleski going to Cincinnati.5

Brennan debuted with the Phillies (also known as Daisies at that time) in a blowout loss in relief on May 19. After the season Sporting Life noted that “Southpaw Brennan was the champion pitcher of the National League when it came to working in small sections of games. He took part in 22 performances and yet only four of these were decisive battles.”6

Brennan finally got his chance to prove his worth at the tail end of the season. On September 26 he pitched a two-hitter in the Phillies’ 9-1 win over the visiting St. Louis Cardinals. After a no-decision in Brooklyn, Brennan defeated the Giants on October 2.

After winning two games and losing none in his rookie season, Brennan split the 1911 season between Philadelphia and Buffalo of the Eastern League. In early June the Phillies sent him, in an optional agreement, to Buffalo for “development.” After joining the Bisons, Brennan led manager George Stallings’ team in pitching (14-8) and threw two nine-inning no-hit, no-run games. The first came on June 25 at Jersey City when he blanked the Skeeters, 1-0, and scored the only run himself. On August 26 he pitched nine innings of no-hit, no-run ball against the same team, only to lose in the tenth, 1-0. After Brennan’s second gem, he was recalled to Philadelphia.

Brennan was with the Phillies for all of 1912, pitching in 27 games, 19 of them starts. He also proved he could hit major-league pitching, batting .254 in 66 plate appearances.

On July 31, 1912, Brennan picked up his 11th victory of the season with a two-hit, 2-0 shutout of the Cardinals in National League Park (not yet renamed Baker Bowl). Though dominant from the mound, he was plagued before and during the game with a sore throat. Brennan said he chewed a piece of black licorice that day, then spat on the slippery ball in order to offset expectorate of the opposing pitcher when using a spitball. However, Ad was not a practitioner of the spitball nor was his opposite number, Rube Geyer.

Within two days Brennan’s “tonsillitis” worsened and he consulted a doctor. Throat cultures suggested that he was suffering early symptoms of diphtheria, and he was taken to Philadelphia’s Municipal Hospital for people with contagious diseases. He was treated with injections of antitoxins and obviously would not return to the mound anytime soon.

Brennan’s actions and his illness created a controversy about the spitball. League President Tom Lynch notified Phillies manager Red Dooin that he would be fined $50 each time one of his players put a chemical upon any ball in play. The Sporting News editorialized, “Why should it be lawful for one pitcher to expectorate upon a ball to make it slippery, and unlawful for another to coat the ball with a substance which will enable him to get a grip upon it is a little beyond the average individual.”7

Brennan pitched one more game in the 1912 season, lasting only four innings against the Cardinals on September 20. He did pitch in the second game of a postseason series against the Athletics in October but was even less effective than in his September start against St. Louis.

Brennan pitched one more game in the 1912 season, lasting only four innings against the Cardinals on September 20. He did pitch in the second game of a postseason series against the Athletics in October but was even less effective than in his September start against St. Louis.

A report to Sporting Life from the Phillies’ 1913 spring training camp proclaimed, “Brennan shows no handicap from his attack of diphtheria last summer. Manager Doolin declares Ad right now has more speed than he ever has had.”8

The Phillies were poised for a pennant run with a pitching staff that included two future Hall of Famers, Grover Cleveland Alexander and Eppa Rixey, 27-game winner Tom Seaton, and the up-and-coming Brennan, whom his manager would call “the left-handed Mathewson of the National League.” Manager Dooin added, “Brennan learns something with every game he pitches, and he is the only southpaw pitcher in the senior circuit league with a ‘fadeaway ball’ [à la Mathewson].” The manager’s statements were supported by coach Pat Moran, who played a major role in Brennan’s progress as a major-league pitcher.9

On the morning of June 30 the Phillies were in first place, holding a tenuous half-game lead over the visitors from New York. McGraw’s Giants rallied to win the morning game, won again that afternoon (the occasion for the “fight” between Brennan and McGraw), then swept the remaining two games of the series, and were never seriously challenged for first place again that season.

On July 3 National League President Lynch suspended Brennan and McGraw for five days, and also fined Brennan $100.10 (The Phillies management was said to have paid Brennan’s fine.)

Brennan made his first start since the McGraw affair the day his suspension was lifted. Sportswriter James Jerpe wrote, “That Quaker fans really believe McGraw deserved a licking was shown by the reception accorded the pitcher when he went to bat for the first time.”11 Brennan pitched eight innings and allowed only one unearned run, but fell to the Pirates’ Babe Adams, who threw a three-hit shutout. Brennan easily won his next game, against the Cardinals. But just as Brennan was pitching the best ball of his career, he was hit just above the knee by a batted ball during the St. Louis game. He paid little attention to the injury at the time and took the mound against Cincinnati on the 16th. Despite his sore leg, Brennan pitched 16 innings to defeat the Reds 3-2. He scattered eight hits and did not walk a single batter.

After that game Brennan took to his bed because of pain in the leg. He was examined by a physician who told him the tissues next to the bone were bruised and torn. Absolute rest was prescribed, lest he might need to have the bone surgically scraped.12 On July 30 Ad returned to the mound on a regular basis.

After Brennan pitched the Phillies to a 3-1 victory over the Chicago Cubs on August 20, his won-lost record was 13-6. In his next start, against the Pirates, he did not last through a six-run fourth inning. Four days later he gave up eight runs on ten hits and left after the second inning. A three-run first inning by the Boston Braves led to another early exit by Brennan on September 6. His best September outing came in a 3-2 loss to Chicago, but after that he was used mostly in relief in games where his team was trailing.

Manager Dooin did give Brennan one more start, at the Polo Grounds on October 4. New York had long since clinched the pennant but the Giants had an extra incentive when facing Brennan. Eight first-inning hits led to the six runs that sent Brennan to the clubhouse. Wrote the New York Times: “When the Giants stepped to bat in the first game, who did they notice in the pitcher’s box but Addie Brennan who mauled Manager McGraw in Philadelphia on June 30, and after rolling him on the ground, proceeded to walk over his smiling face with spiked shoes.”13

During Brennan’s disastrous final six weeks of the 1913 season, he picked up only one victory, in a two-inning relief stint against Boston in late September.

During the offseason, Brennan, like many other major leaguers, challenged Organized Baseball’s reserve clause, and in January 1914 he signed a contract to pitch for more money with Chicago of the Federal League. Despite his poor performance late in the previous season, he received a three-year contract at an annual salary of $4,300. Sporting Life reported that Brennan “jumped to the opposition for $500 advance money … and coaxed (catcher) Bill Killefer to follow him. Ad was promised an additional $500 bonus if he could convince Tom Seaton to also defect to the Federal League.” Seaton was Brennan’s best friend on the Phillies and one of the top pitchers in 1913, leading the National League in wins, innings pitched, and strikeouts. Ad traveled to Seaton’s home in Pueblo, Colorado, and persuaded his good friend to join him in the new league.14

There is no question that Brennan’s decision to defect to the Feds was best for him personally. Considering his arm problems, the tightwad owner of the Phillies, William F. Baker, would never have paid him a cent after his arm woes in 1914, but he was guaranteed three years of salary under the Federal League contract. His short-term financial future secure, on January 28, 1913, Brennan married 21-year-old Portia “Pertie” Durnell, a stenographer for the English Tool and Supply Company in Kansas City. It was Brennan’s second marriage; a short-lived union from his time in Iola was dissolved in May 1912 when he was granted a divorce from Susie Brennan.15

After viewing a Chifeds intrasquad game, Sam Weller of the Chicago Daily Tribune wrote that Brennan was in fine form: “He displayed the most tantalizing slow ball the boys have looked at and he could follow with a fast ball one that was dazzling.”

Since Chicago’s new home park at North Clark Street and Addison was not ready for Opening Day, the team spent the first week of the season on the road, winning only two of seven games played. Brennan started in Kansas City, allowing six hits and three runs before being removed for a pinch-hitter in the eighth inning. He threw a complete game in his next outing but lost to St. Louis, 4-3, on a ninth-inning run.

When Brennan was thrashed after relieving the starting pitcher in the third inning of a game on April 26, he acknowledged that his left arm had been sore since the season opened. Sam Weller wrote that the “zip” was missing from his fastball, and his curve did not have its usual drop. Brennan was bothered by physical problems all season and started only 11 games for Chicago.16 In one of them, he beat the Brooklyn Tip Tops 3-1 on May 9 and threw his bat toward the mound when he thought the opposing pitcher intentionally threw at his head. On May 19 he shut out Pittsburgh on three hits, two of them of the fluke variety. But his short-term success was not sustained. That June a physician told him the trouble with his sore pitching arm was due to inflamed tonsils with the infection extending to the muscles of his shoulder. Brennan was of little value to his team the remainder of the 1914 season.

In early September manager Joe Tinker decided to try Brennan in a game with a comfortable lead over Indianapolis. Two walks and a hit batsman loaded the bases and Brennan was done. Tinker was quoted as saying Brennan “could not have found the plate with a handful of rice.”17

For all their money, the Chicago Federals got only five wins in ten decisions from Brennan. His troublesome left arm made only negligible improvement over the offseason. In 1915 he reported to spring training 17 pounds heavier than a year earlier, but his pitches did not have the speed of his days in Philadelphia. He continued to struggle for the newly christened Chicago Whales. In Brennan’s 5-4 loss in Newark on May 7, he lasted only 1? innings, allowing seven hits and five runs. The Whales attempted to ship Brennan and a third-string catcher to Springfield of the Colonial League, which had a financial relationship with the Federals. However, the Springfield club refused to pay for their transportation, so manager Tinker decided to keep Brennan with the club for the time being.18

Just when Chicago’s beleaguered pitching staff needed help the most, Brennan had his most successful stretch as a Federal in late August, though he had little to show for it in the won-lost column. On August 1 in Chicago, he pitched shutout ball for eight innings before Newark tied the score in the ninth. The visitors won it in the 12th. Brennan got his revenge on August 10 in Newark with his best outing as a Federal Leaguer. Only three Peps hit safely in his 7-0 shutout. Then he lost his next three decisions and finished the season with three victories and nine losses. In September baseball’s “arm specialist” Bonesetter Reese pronounced Ad’s pitching arm sound and able to pitch.

During the offseason the Federals made peace with Organized Baseball and Whales owner Charles Weeghman was allowed to buy a controlling interest in the Cubs. This meant the players from the Whales and Cubs would be competing for jobs. In late February 1916 Cubs manager Joe Tinker announced that Brennan would pitch for St. Paul of the American Association and the Cubs would help pay his guaranteed salary for the final season of his three-year Federal League contract. Instead of St. Paul, Brennan on May 1 agreed to pitch for the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. He was not impressive was released in less than a month. However, another Atlanta hurler had to leave the team because of illness and Brennan was reinstated,19 and after the arm troubles of his two seasons in the Federal League, he was rejuvenated in Georgia. On May 20 he shut out Little Rock and three days later allowed only one run in a victory over Memphis. Brennan completed the 1916 season with a 16-8 record and returned the following year to help pitch the Crackers to the Southern Association championship. He threw 210 innings in 1917 and won 12 games, losing 13.

Brennan won seven games and lost 11 in the first three months of the 1918 season, then got another shot at the major leagues in June when he was sold to the Washington American League club. Four days after joining the Nationals, Brennan started against the New York Yankees. He pitched five innings and received a no-decision after allowing two runs and ten hits. Brennan got another shot on July 6 and walked three of the four batters he faced in a relief appearance against the St. Louis Browns. Two days later Washington released Brennan. He finished the season with the Cleveland Indians, where he pitched his final inning of major-league baseball in a relief role on July 27. Including those three games with the American League Brennan pitched in 129 major-league games and posted a record of 37-36 with an ERA of 3.11.

Brennan returned to the Crackers in 1919, but in May the Atlanta club suspended him for “an infraction of rules.” Two months later he was released to Columbia of the South Atlantic Association, for whom he went 14-19 and batted .279.

By 1920 Ad and Portia were residing in Kansas City at the home of his father-in-law. He continued to pitch, mostly in the bush leagues of Missouri and Kansas. In August 1922 an advertisement for the Chillicothe (Missouri) semipro club featured Brennan and noted that he had struck out 23 batters in the previous game against Shackleford.20

After his days as a baseball player had run their course, Addie and Portia lived in Kansas City the rest of their lives. (They had no children.) Ad worked as a repairman for the Kansas City Street Car Company and later as chief clerk and timekeeper. The 1940 Kansas census noted that his annual salary from the city was $2,279. Brennan had coached baseball at Fulton High School during his time with Atlanta, and resumed his work with young baseball players after his playing days.21 Brennan-coached teams won Ban Johnson League championships in 1932, 1937, 1940, 1946, and 1948. Among the players he coached was a fireballing pitcher, Mort Cooper, for whom he arranged a pro tryout and who became an ace hurler for the St. Louis Cardinals.22

Brennan retired from his duties as manager in March 1949 after a connection with the Ban Johnson League since 1931. In 1957 he was inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame.

Brennan died of cancer on January 7, 1962, after a year of hospitalizations and two surgical procedures. He was buried in Kansas City’s Forest Hill Cemetery. Twenty years later Portia was interred beside him.

Brennan’s obituary in The Sporting News, headlined “Brennan Death Recalls Kayo Over McGraw,” summed up the totality of his baseball career with a rehash of that affair. Brennan was quick-tongued as a young player but mellowed over the years. He regretted the incident, perhaps because the assault on John McGraw was almost always brought up when Brennan’s baseball career was referenced. “I guess I was just too quick on the trigger,” he said once when asked about the McGraw fight. “I’d rather not elaborate on it and want to forget the whole thing.”

It was widely reported that Brennan sought to contact McGraw when the manager visited Kansas City in 1932. “Looking for me, is he?” snarled McGraw. “I don’t want to see Ad Brennan. That all happened years ago and it’s all over. Brennan wrote to me last summer but it’s too late now.”23

Photo Credit

George Grantham Bain Collection; Library of Congress Prints & Photographs

Sources

In addition to sources noted, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com for major- and minor-league statistics. In the absence of statistics in Baseball Reference for some minor-league seasons, records printed in The Sporting News and Sporting Life were utilized.

Notes

1 “Addie Brennan Knocked Down Muggsy M’Graw,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 1, 1913; “Brennan Punches McGraw in Fist Fight After Game, Philadelphia North American, July 1, 1913; “Philadelphia Scene of the Latest Slugging Match,” Sporting Life, July 12, 1913.

2 “Addison Brennan,” Ancestry.com.

3 Paul O’Boynick, “Ad Brennan Played Big Role in B.J. League,” Kansas City Star, January 8, 1962.

4 Sporting Life, August 21, 1909.

5 Anaconda (Montana) Standard, July 6, 1913.

6 Sporting Life, November 12, 1910.

7 “Warning to Dooin,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1912.

8 Sporting Life, March 29, 1913.

9 Sporting Life, August 16, 1913.

10 Philadelphia Inquirer, July 4, 1913.

11i Pittsburgh Daily Gazette, July 11, 1913.

12 “Pitcher Brennan Injured,” Pittsburgh Press, August 7, 1913.

13 “Giants in Batting Rampage Against Philadelphia Pitchers,” New York Times, October 5, 1913.

14 Sporting Life, February 28, 1914.

15 Sporting Life, June 1, 1912.

16 “Wellerisms,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 27, 1914.

17 Chicago Daily Tribune, September 7, 1914.

18 Chicago Daily Tribune, May 19, 1915.

19 Sporting Life, June 3, 1916.

20 Chillicothe (Missouri) Constitution, July 1, 1922.

21 Atlanta Constitution, April 20, 1919.

22 Kansas City Star, January 8, 1962.

23 The Evening Independent, St. Petersburg, Florida, April 6, 1932, 22.

Full Name

Addison Foster Brennan

Born

July 18, 1887 at La Harpe, KS (USA)

Died

January 7, 1962 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.