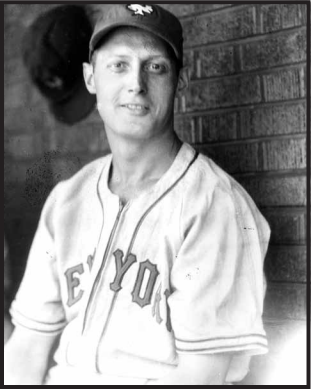

Roy Zimmerman

The archives of baseball are filled with the stories of players whose major-league careers spanned one year, others who played a decade or more, and an unfortunate few who only grabbed a cup of coffee, arriving after years in the minors and leaving after a scant handful of games that gave their careers a certain kind of baseballic mystique. And then, there were the players who fall somewhere between. Roy Franklin Zimmerman, a first baseman from the Pennsylvania coal country who could hit home runs and field very well, spent years touring America courtesy of several minor-league teams. His brief major-league career, although more than a cup of coffee, lasted barely a month, and therein lies a tale mixed up with triumph and woe.

Roy Zimmerman was born on September 13, 1916, in Pine Grove, Pennsylvania, to Raymond and Mary Ellen (Fisher) Zimmerman, the second of three sons. In 1910 the predominant occupation in Pine Grove was miner, or occupations associated with the mining industry. Raymond Zimmerman worked for a local tannery, and by 1931, when he died, his occupation was house painter, a trade inherited by his eldest son, John. Roy started playing baseball around Pine Grove, left high school after three years, and had enough athletic skill to be noticed on the baseball diamond. He was lucky. Earl “Sparky” Adams, a homegrown baseball player who spent 13 years in major-league baseball, mostly with the Chicago Cubs, had just retired in 1936 and Zimmerman became his local heir apparent. Roy played for the town teams of Rock, Ravine, Donaldson, Tremont, and Pine Grove in central Pennsylvania and acquired the nickname “Boom.” Adams hoped he would be the next local talent to make it all the way to major-league baseball.

Digging into Roy Zimmerman’s background reveals a bit of confusion about his date of birth. All baseball references, including Total Baseball, The Baseball Encyclopedia,and Baseball-Reference.com, list his birthdate as September 13, 1916. Information about the first year of his minor-league career puts his age at 20 in 1937, a much more attractive age to start a baseball career than 23, his apparent real age, would have been. Each census in 1920, 1930, and 1940 requested a person’s age on April 1, and since Roy was born in September, it appears that his parents dutifully followed the rule. In 1920 his age was listed as 6 years; in 1930, his age was 16; and, most interesting of all, in 1940, while he had informed the baseball world that he was 24, he listed his age as 27 when the enumerator made the rounds less than a month before his birthday. By the time Zimmerman joined the New York Giants, he would turn 31, not 28, in September 1945.

Adams introduced Zimmerman to his contacts in the Chicago Cubs organization and took him to a tryout in Philadelphia. Roy began his minor-league career in 1937 with the Perth-Cornwall (Ontario) Bisons of the Canadian-American League but played most of the season for the Moline Plow Boys of the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three-I) League. He then spent the next two years with Moline and the Columbia Reds of the South Atlantic League, where he overslept one day and lost the first-base job. He bought an alarm clock but he would still occasionally fall asleep at inopportune times.

By 1940 Zimmerman was with the Tyler Trojans of the East Texas League and later returned to the South Atlantic League with the Macon Peaches. For the 1940 US Census, he recorded his occupation as “baseball player,” noting also that he worked 26 weeks per year and was married to Mary (Seiler) and had a one-year-old daughter named Gail. He started the 1942 season with the Greenville Spinners and later returned to Macon. In 1943 Zimmerman rose higher in the minors when he signed with the Kansas City Blues, spent part of 1944 with the Newark Bears (both teams were Double-A affiliates of the New York Yankees), and later returned to Kansas City. In 1945, after a brief holdout over a contract disagreement, Zimmerman again joined the Newark Bears, where he was in a good location to be seen by local major-league teams. He came to Newark trying desperately to shake a batting slump, having hit only six homers in 1943 and 1944, but he changed his approach by moving closer to the plate and began hitting home runs. Major-league scouts took notice that Zimmerman led the Bears in home runs with 32 — the most he had ever hit in any previous professional season was 12. He also batted .282 with15 doubles, 4 triples, and 81 RBIs. They watched him turn into a candidate for the International League’s most valuable player.

Life was changing for the better as World War II was coming to an end, first in Europe and then in the Pacific in August of 1945. Not all players who had gone off to war had yet returned nor were they ready to resume their careers in baseball during the few weeks left in the 1945 season. Just as many careers today are boosted by one player’s fortune or misfortune, so was Roy Zimmerman’s career extended by the New York Giants’ need for a first baseman.

The Yankees sold Zimmerman to the Giants on August 7, because general manager Larry MacPhail and farm chief George M. Weiss doubted he could do the Bombers as much good at first base during the remainder of the season as Nick Etten could.1 To be on the safe side, Giants manager Mel Ott, who was not sure what he’d need to finish the season, also brought up Mike Schemer, a promising first baseman, from the Jersey City club and sent veteran Phil Weintraub along with $20,000 cash down to Newark. Johnny Mize, the Giants’ veteran first baseman, had not yet returned from the Navy but was expected to eventually pick up his old job once spring training opened in 1946. After years of toiling away in the minors and accumulating a record he could be proud of, Zimmerman told the Newark club that he wanted part of his purchase price as a bonus because without it, the expenses of living in New York City necessitated a higher salary, and he knew that his playing time would decrease once Mize returned.2

Zimmerman was disappointed with the deal that sent him from the Yankees organization to the Giants. Back in March, disillusioned with baseball because the Yankees hadn’t given him a tryout, he had nearly decided to quit but wanted to give his baseball career one more try. If he didn’t make it in 1945, he had vowed, he would not only “hang up his spikes but he’d nail them to the wall.”3

Mel Ott was irate. “’He’ll never get a bonus from us for signing,’ snapped Ott when asked about Zimmy’s status yesterday. ‘He has been offered a contract bearing a substantial increase over what he got with the Bears, and if he continues his tactics he can go back to the minors as far as I am concerned,’ continued Ott. ‘It is not up to the Giants to give him a bonus.’”4

Ott could have been happy about the prospect of having a hitter with Zimmerman’s reputation in his lineup. The Giants had acquired him for one reason — he could hit home runs, especially to right field, where the stands at the Polo Grounds were only 259 feet from home plate, just a mere pop fly for Boom Zimmerman, who hit half of his long balls more than 350 feet. He had hit homers in every International League park except Baltimore, a record bested only by Dixie Walker in 1935. 5

Mike Schemer immediately looked like the better option, and he played his first game with the Giants on August 8. Zimmerman held out for two weeks, while Giants owner Horace Stoneham and manager Ott declined to give in to the demand. The New York newspapers were unsympathetic, and called on Zimmerman to realize “the supply [of baseball players] is now catching up with the demand.”6 While Zimmerman was left suspended by the Giants, Schemer was tearing up the ballparks around the league, hitting an impressive .385 in his first 10 games and handling first base like the big leaguer he’d just become. Zimmerman came to the sensible conclusion that he couldn’t fight the Giants, relented, and agreed to sign without a bonus. But Schemer wasn’t about to give up first base to him, and Ott, realizing he had a good hitter in Zimmerman, thought he might eventually be of use in the outfield, although whether he could hit ’em in the Polo Grounds as well as he did in the minors was yet to be determined. Although he had been knocking balls out of the park at every opportunity, he was not inspired to bring his talents to the National League. Zimmerman still wanted to be a Yankee.7

With his average an impressive .346 on September 3, Schemer was knocked out of the lineup for two weeks, crippled by infected boils on his arm. Ott turned to Zimmerman to replace Schemer at first base. Roy socked three homers during Schemer’s convalescence, and ultimately played in 27 games down the stretch, 25 at first base, one in right field, and one as a pinch-hitter. By the end of the season, he had come to bat 98 times, hit five home runs, knocked in 15 runs, and finished with a .276 average, but he could not singlehandedly make up for what was missing, for the Giants “lacked that little extra zip … lacked a bell cow, a lead dog or an anchor man, whatever one wants to call it.”8 They finished the season in fifth place, 78-74.

As the end of the 1945 season approached, Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler yearned for a new golden age in baseball and proposed to invest $50,000 developing an incubator of stars on America’s sandlots and in its high schools, a project that would “give the game back to the kids.”9 The funds would be used to supply equipment; returned war veterans who no longer were able to play baseball would be used in the development program. Roy Zimmerman had felt overlooked many times during his long journey to the top of his game, and now he again felt cast aside. He was not about to retire to a coaching job and he didn’t need a bunch of teenagers breathing down his 28-year-old neck, despite the proposed rule that would bar major-league clubs from signing teenage players. With the returning veteran players, who certainly deserved their old positions, and now with baseball looking to develop new and younger talent, where was he expected to find the interest and attention he needed to stay in the place where he had long been toiling to reach?

The International League’s most valuable player in 1945 was Sherman Lollar of Baltimore with 47 votes, Zimmerman received 6, as his name and reputation faded into the postwar baseball news. Spring training for the 1946 season was several months away and Zimmerman would be given another chance. Two years before, the Giants had no first basemen, and now they had five — Mize, Weintraub, Schemer, and Babe Young, as well as Zimmerman, and they could all be in contention for the job in 1946 along with Charley Price, recently discharged from the service; Norman Jaeger, who joined Jersey City; and Cotton McCasky, coming up fast in their farm system. The outlook did not look good for Boom Zimmerman.

He arrived at spring training in March 1946 ready to give major-league baseball another try but was expected to be carried by the team as a utility player and pinch-hitter, a situation he did not find very inspiring. Then one day the Giants’ Danny Gardella and Sal Maglie revealed that they had been approached by the Pasquel brothers of the Mexican League, who waved around fistfuls of money and asked if they knew of any other potential prospects they might acquire. Zimmerman and George Hausmann stepped right up to consider jumping to the Mexican League, and on April 1, when Giants owner Horace Stoneham found out they had been offered contracts by the Pasquel brothers, and despite not yet having decided to accept, they were both fired.

Mel Ott was once again irate as a mass exodus of New York Giants players headed south of the border. Giants secretary Eddie Brannick dismissed the players, saying: “With all the good service players returning, it looks like the Mexican League is getting all the debris. They don’t know what they’re up against playing down there.”10 The lure of big money and the rejection by the Giants organization was enough to seal the deal. “We’re going to catch an airplane to Mexico City today,” Hausmann said, “since that’s the way the Giants want it.”11 Roy Zimmerman left a $6,000 contract behind and was offered double that plus a $5,000 signing bonus and $1,000 traveling expenses. “I couldn’t draw that kind of dough up here, and with me it amounts to more than the figures quoted.”12 His chance of securing a steady job had disappeared in New York. Seeing an opportunity to make an attractive amount of money in a short time, and now cut loose from New York, he joined fellow ex-Giants Danny Gardella, Ace Adams, Harry Feldman, Tom Gorman, and George Hausmann among the 17 players who headed into uncharted territory. Harry Grayson, sports reporter for the NEA syndicate, commented on the Mexican League: “For 70 years owners have been telling players to sign or ‘else.’ At last the noble athletes have the ‘else.’ And when leagues that have raised admission prices can’t successfully stave off the advances of a Mexican venture playing to a total population of less than 3,000,000 and force a player like Dick Siebert to jump to a radio mike, they are in grave danger of losing their major standing — in the eyes of the public, at least.”13 Zimmerman signed on as Nuevo Laredo’s first baseman.

Happy Chandler was not happy. He immediately imposed a five-year suspension if any of the players failed to return within 10 days of Opening Day, although no one knew if those suspensions would hold up. Giants officials reluctantly admitted, off the record of course, that their low salaries might have inspired many of their jumpers to depart, and the only remedy might be increasing player salaries. Zimmerman and Hausmann had both been vocal about their criticism of Mel Ott’s management style. One Giants pitcher was quoted as saying, “You can’t blame some of the players for getting as much money as possible while they can. They probably remember last season when the Giants drew more than 1,000,000 paid admissions. Most of us expected a bonus, but we received two baseballs each, autographed by all members of the club.”14

Horace Stoneham said he had no complaints about the missing players. No valuable talent had been lost, he thought, although he admitted the Giants lost considerable money developing some of the players who had jumped. He figured Zimmerman cost him $30,000, but he’d write off the financial loss as an investment in development that did not pan out.15 The New York Giants seemed to be playing the role of farm team for the Pasquel brothers and the Mexican League. Two theories were put forth by observers. The team, being a second-division club, used mediocre talent during the war and as the veterans returned, the players who feared being discarded became lucrative fodder for Mexico. Also, once Danny Gardella, Sal Maglie, and others jumped, the Mexicans were able to establish close contacts inside the Giants locker room.16

The Mexican adventure was a disaster. The stadiums were shabby, and crowds sometimes turned violent when the fans disagreed with an umpire’s decision. Travel was arduous as well as dangerous at times. Just two weeks into the season, Zimmerman was injured, did not play again for a week, and was replaced by Gorman. A jinx seemed to hover over many of the American jumpers. Injuries were frequent, and Zimmerman suffered another setback when he was spiked in a first-base collision with Alfredo Gerard, the Puerto Rican outfielder of the San Luis Potosi team, on May 9. The Pasquel brothers miscalculated how much the American players would enhance revenues; their lavish contracts became a burden on the league; and the players soon realized the offers were too good to be true. Nuevo Laredo’s manager, Erasmo Lares, announced his team would not play in 1947 unless the players gave up the demands for higher salaries. Jorge Pasquel said all the players from 1946 would again play in Mexico, but Lares, insisted: “No puede y no pagará.”17 The club simply could not pay what the players were asking. Pasquel attempted to downplay the salary demands, assuring he would sign more great talent for the 1947 season, but also complained that Havana had lured away several of the Cuban and American players he had expected would return to Mexico.18

What the players found when they returned home in 1947, humbled by the experience and hoping to be welcomed back, were not open arms, nor forgiveness for jumping to the Mexican League. They were met with Happy’s five-year ban and the commissioner standing firm. There was little sympathy for their plight. In March 1949, pitchers Max Lanier and Fred Martin, formerly of the St. Louis Cardinals, met with John L. Flynn, a New York attorney who announced that lawsuits totaling millions would be filed in behalf of a group of men on the banished list. “Baseball’s chastised children”19 wanted to get back into the game, but the players were divided on how to accomplish what seemed impossible. “We all want to play baseball, and it’s a cinch we never will again if we try to sue the game,”20 Mickey Owen contended. He held out hope that Chandler would relent and lift the ban without having to resort to litigation. Owen talked with a number of players, including Hausmann, Zimmerman, Maglie, Martin, Harry Feldman, and Lou Klein, and they all assured him they preferred to sit out their suspensions, and that a lawsuit would only make their plight worse. There was skepticism on both sides of the issue. Perhaps Owen was making progress with Chandler, but Attorney Flynn promised, “just wait until our suits are filed. You may find more in them than you think.”21 He declined to name the men he was working with but said $5 million was a “low” estimate of the total damages that would be asked.22 Already pending in courts was a $300,000 suit filed by Danny Gardella, who contended that his banishment deprived him of a chance to make a living.

There was a chance that the players might win their suit and be handed an astronomical amount of money. Chandler considered the situation and on June 6, 1949, he announced that Major League Baseball was now ready to welcome back the players who participated in the Mexican adventure of 1946. He decided to “temper justice with mercy” and said three years served was an adequate exile. “Of course I would not invite them to return if I were not certain they would be rehired,” the commissioner commented.23

A few of them were rehired, others were not. Mickey Owen joined the Chicago Cubs and remained with them for three years. George Hausmann returned to the Giants for 16 games in 1949, and Harry Feldman pitched just three games that year. Roy Zimmerman did not return to the Giants and did not appear on a major-league team again. Danny Gardella, playing for a minor-league team in Canada, did not accept the reinstatement offer. Max Lanier and Fred Martin planned to sue for $2.5 million. “This fight against Organized Baseball has cost me a lot of money and you can take it from me that I want to get some of it back before I sign any more contracts,”24 said Lanier. They sued the commissioner, both league presidents, and all the club owners, alleging that baseball was a monopoly in violation of antitrust laws, and they challenged the legality of the reserve clause. Attorney Flynn added confidently, “Sure, we’re going ahead.”25

There was no major-league comeback for Zimmerman. He instead joined the Drummondville Cubs of the Quebec Provincial League and waited out Chandler’s decision in 1949. In 1950 he signed with the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League, appeared in 138 games at first base, and hit 20 homers with 114 RBIs. That would be as close as Zimmerman got in his attempt to return to the major league. He played in 61 games for Tulsa in the Texas League in 1951. His baseball-playing years ended there.

Zimmerman returned to Pine Grove, Pennsylvania. He worked as a carpenter with Union Local 287 and frequently played in baseball games in Pine Grove and surrounding towns. His last plate appearances were with the St. Clair Oldtimers Baseball Association. He died in Pine Grove, on November 22, 1991.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com.

The Sporting News.

Klein, Alan M., Baseball on the Border (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997).

Marshall, William, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Baton Rouge Advocate.

Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times.

Omaha World Herald.

La Prensa (San Antonio).

The Register-Republic (Rockford, Illinois).

Carroll, Sharman L., Tremont (Pennsylvania) Historical Society.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, August 16, 1945, 4.

2 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

3 “Ebbets Field Ganders at Zimmerman Today,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 19, 1945, 17.

4 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 17, 1945, 11.

5 “Ebbets Field Ganders At Zimmerman Today.”

6 United Press, Baton Rouge Advocate, August 18, 1945, 10.

7 “Ebbets Field Ganders at Zimmerman Today.”

8 The Sporting News, September 27, 1945, 8.

9 “Majors, Minors Set Aside Funds,” UP, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 17, 1945. 11.

10 Harry Grayson, “If Mexican Jumping Business Keeps Up Major Leagues Will Lose Their Standing,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, April 3, 1946, 6.

11 “Giants Lose Three Players; That’s No Joke to Mel Ott,” UP, Trenton Evening Times, April 1, 1946, 13.

12 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 1, 1946, 11.

13 Harry Grayson, “The Scoreboard,” Mount Carmel Item, April 3, 1946, 6.

14 H. Earl Barber, “Mexican League Throws Scare Into Most Major Loop Owners,” UP, Baton Rouge State Times, April 3, 1946, 14.

15 “Giants Jump (Into Stride After 2 Jumps to Mexico),” The Sporting News, May 2, 1946, 2.

16 Ibid.

17 “Nuevo Laredo No Jugarā en la Liga Mexicana,” La Prensa (San Antonio, Texas),

March 5, 1947, 7.

18 Ibid.

19 “Players Split on Court Case,” Associated Press, Register-Republic (Rockford, Ilinois), March 8, 1949, 12.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 AP, Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, March 7, 1949, 21.

23 “Suspensions Lifted on Ousted Players,” International News Service, Omaha World Herald, June 6, 1949, 13.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

Full Name

Roy Franklin Zimmerman

Born

September 13, 1913 at Pine Grove, PA (USA)

Died

November 22, 1991 at Pine Grove, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.