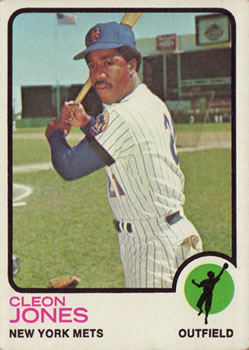

Cleon Jones

There are other great moments in Mets history, like The Buckner Ball and The Grand Slam Single, but surely any listing of the most significant moments in Mets history, particularly of the Mets’ first two decades, would have to include these three. The common thread for these three incidents is Cleon Jones, the first consistent, legitimate offensive threat ever to play for the Mets.

There are other great moments in Mets history, like The Buckner Ball and The Grand Slam Single, but surely any listing of the most significant moments in Mets history, particularly of the Mets’ first two decades, would have to include these three. The common thread for these three incidents is Cleon Jones, the first consistent, legitimate offensive threat ever to play for the Mets.

October 16, 1969—Game Five of the World Series. The Mets led three games to one. The powerful Orioles jumped out to a 3-0 lead and the Mets needed to do something to turn the game around. In the bottom of the sixth inning, Dave McNally’s pitch to Cleon Jones hit the dirt and bounced into the Mets dugout. Umpire Lou DiMuro called it a ball. Jones had started toward first believing he was hit by the pitch. DiMuro disagreed until manager Gil Hodges came slowly out of the dugout, showed DiMuro the ball, and pointed at a small smudge of shoe polish. DiMuro sent Jones to first. Donn Clendenon followed with a home run that tightened the game and began the comeback that won the game and the World Series.

October 16, 1969—“Come on down, baby. Come on down.” Those were the words of Cleon Jones as he spoke to Davey Johnson’s fly ball with two outs in the ninth inning of Game Five of the 1969 World Series. No Mets fan will ever forget watching that ball settle into his glove and seeing Jones almost kneel upon catching it. No Mets fan will ever forget the elation showed by Jones as he then raced toward center field to celebrate with lifelong friend Tommie Agee.

September 20, 1973—Going into this game against Pittsburgh, the Mets were in third place, 1 ½ games back of the Pirates. The Mets had scored a run in the bottom of the eighth to tie the game, 2-2. The Pirates scored again in the ninth. The Mets answered in the bottom of the inning to force extra innings. In the 13th inning, with the game still tied, Dave Augustine hit a long fly to left. It was well over Jones’s head and would clearly score Richie Zisk from first, if it wasn’t a home run. But the ball hit the corner of the top edge of the wall, bouncing directly to Cleon Jones. He turned and threw to Wayne Garrett, who relayed it to Ron Hodges to nail Zisk at the plate. The Mets went on to win in the bottom of the inning, starting the final surge that led the Mets to the division title, the World Series, and almost another world championship.

Cleon Jones was the linchpin to all these moments, even though he is somewhat overlooked in the pantheon of great Mets today.

Cleon Joseph Jones was born on June 24, 1942 in Plateau, a section of Mobile, Alabama, whose most notable characteristic was the ever-present smell from the local paper mills. According to Jones’s autobiography, race didn’t really seem to matter much during daily life in the pre-integration South. There were surely some problems but most of the time blacks and whites simply behaved as local custom prescribed. Jones downplayed one aspect of this, however: race problems caused Jones to grow up without his father in the home. One day in 1945, his parents, Joseph and Carrie Jones, were waiting to take a bus back home. Carrie Jones was standing in front of a white woman in line. That apparently offended a white man who grabbed Carrie by the hair. Joseph responded by beating the man rather severely. Rather than risk trial in the Alabama courts, Joseph quickly relocated to Chicago, leaving Cleon, and older brother Tommie Lee, to be raised by their mother and their grandmother, who was affectionately known as Mama Myrt.

Two years later, Carrie Jones moved to Philadelphia to find work. That was the family arrangement for about five years. Life changed dramatically for Cleon when his mother died in Philadelphia. In his autobiography, Jones relates the emotion the family experienced on hearing the news, but also the stability and love provided by his grandmother. “I guess Tommie Lee and I started crying, too. But when my grandmother looked at us and sobbed, ‘My poor babies, you have no one now,’ we knew she was wrong. We had Mama Myrt.”

Cleon Jones’s life always involved sports. There were baseball and football games in the streets and vacant lots of Mobile. The odd arrangement of some of those street games led to Cleon batting right-handed while throwing left-handed. He told Maury Allen how it happened:

There was this one field that we put some old shirts down for bases. Behind right field there was this little creek and behind left field, well, man, it just went on and on for miles. We played our games there and after a couple of games I had lost four or five balls when I hit them left-handed into the water. We didn’t have too many real baseballs so when the other guys came to me and said, ‘You better stop doing that or we ain’t got no more baseballs here,’ I just turned around. That’s how I became a right-handed hitter. I just wanted to save those balls.

Athletic success at County High followed, where Cleon teamed with Tommie Agee in both baseball and football. Success there led to playing college football for Alabama A&M. After one year there, Clyde Gray, a man from Mobile, tried to get the Kansas City Athletics and New York Mets to look at Jones. Tommie Agee had signed with the Cleveland Indians and Gray thought Jones had a future in baseball as well. Gray regularly worked to try to help young blacks from Mobile. Some help was needed. After all, this was still only 15 years after Jackie Robinson integrated the major leagues. The Athletics showed no interest in Jones, but the Mets did and he signed with them on July 5, 1962. Because of how late in the season the signing took place, Jones went back to college for a while.

Jones’s professional career started in 1963; he hit a combined .317 with Raleigh in the Carolina League and Auburn in the New York-Penn League. He also made his major-league debut that year, coming in as a defensive replacement for center fielder Duke Carmel on September 14. The abysmal Mets were eager to find young stars but Jones was not ready. He finished 1963 with just two singles in 15 at-bats. In 1964, the Mets kept Jones in Buffalo in the International League for the entire season. He turned in a solid year, batting .278, slugging .442, and hitting 16 homers in 500 at-bats.

In 1965, Jones found himself in New York on Opening Day. He appeared as a pinch-hitter for Tom Parsons in the Mets’ 6-1 loss to the Dodgers. Two days later, on April 14, Jones made his first start. With no hits and two strikeouts in his first four at-bats, the debut was less than inspiring. But the Mets saw a hint of what was to come when Jones singled in the 11th, scoring Joe Christopher and Danny Napoleon to bring the Mets to within one run of the Astros, though they still lost the game.

By May 2, with Jones hitting .156, it was obvious he was still not quite ready, so it was back to Buffalo. He played 123 games for the Bisons. For a while, Jones really struggled in Buffalo. One reason for that, according to Jones, was Buffalo manager Sheriff Robinson’s insistence that Jones try to pull the ball and hit home runs. When Robinson went up to the majors to be a coach for Wes Westrum, Kerby Farrell, a former major-league manager who had befriended Jones during training camp in 1963, became the Buffalo manager. He encouraged Jones to ignore the pressure to pull and resume hitting to all fields. Though his numbers were still a little lower than in 1964, he began to get his swing back and was establishing himself as a solid ballplayer.

Jones was a September call-up for the Mets, appearing in 17 games from September 3 until the end of the season. Though he never got his batting average higher than .169, Jones had seen his last days in the minor leagues.

On Opening Day 1966, Cleon Jones batted leadoff as right fielder for manager Wes Westrum. In the bottom of the eighth, Jones hit a home run off Braves starter Denny Lemaster, giving the Mets a 2-1 lead. Unfortunately, Jones committed an error in the ninth that led to a run as the Mets fell, 3-2. By the end of the season, Jones had batted .275 with eight home runs and 16 stolen bases. He finished tied for fourth in the Rookie of the Year voting, with Randy Hundley and Larry Jaster, behind winner Tommy Helms (Sonny Jackson and Tito Fuentes were second and third, respectively).

Jones’s strong 1966 was followed by a very trying 1967. He started the season 0-for-18 before finally getting a hit. Before long, Westrum was giving Jones a lot of time on the bench. He didn’t get his batting average above .150 until June 3. After one game, Westrum blasted Jones in the press, further discouraging the young outfielder. Veteran Ken Boyer encouraged Jones to not let the treatment get to him. Things did finally start to turn around. Beginning with the second game of a June 18 doubleheader, Jones had a 10-game stretch during which he hit .341. He batted .277 for the remainder of the season, leaving him at .246. On a 101-loss Mets team, that wasn’t terrible, and it was almost an achievement given how long he’d struggled.

A big change, not just for Jones, but for the entire team occurred on November 27, 1967. Gil Hodges came to the Mets as manager in exchange for $100,000 and pitcher Bill Denehy. Hodges, a star with the 1950s Brooklyn Dodgers and an Original Met in the last years of his playing career, brought a quiet strength and a winning attitude to the perennially losing Mets. Jones called Hodges the best manager for whom he ever played. Hodges treated his players like men, expecting much, but also supporting and encouraging them.

Another big change, of a particularly personal nature for Jones, occurred on December 15. Tommie Agee, Jones’s high school friend from Mobile, was traded to the Mets by the Chicago White Sox along with Al Weis for Tommy Davis, Jack Fisher, Billy Wynne, and Buddy Booker. Having a poised, supportive manager and having his good friend on the Mets gave Jones a much-needed confidence boost.

Jones started slowly in 1968. At the start of June he was hitting in the .220s, but he then hit in 11 straight starts. By the last day of the season, his average was up to .298. A l-for-5 finish against Chris Short dropped him to .297, but it was clear that Jones had established himself as a solid major leaguer. Agee, however, had a dismal 1968, featuring a beaning and several long hitless streaks. But in 1969, the friends from Mobile, along with the rest of the Mets, shocked the baseball world.

Casey Stengel was once quoted as saying that man would walk on the moon before the Mets would win the pennant. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. Less than three months later, on October 16, 1969, the Mets became world champions.

Cleon Jones was as big a part of the Mets championship as anyone. He batted .340 with an on-base percentage of .422. He led the team in batting average, on-base percentage, slugging, hits, doubles, stolen bases, walks, and even hit by pitches. He was second on the team in RBIs, one behind Agee. He started in the All-Star Game (two singles, reached on an error, and scored twice) and finished seventh in the league Most Valuable Player voting, behind winner Willie McCovey and teammates Tom Seaver and Tommie Agee.

During the first National League Championship Series in history, Jones batted .429 with a homer, two doubles, and four RBIs. The Mets hit .327 overall in the three-game sweep of Atlanta.

In the World Series win over Baltimore, Jones hit only .158, but he was in the thick of things. His foot and his knee live in Mets immortality. He was hit by Dave McNally’s “shoe polish” pitch and scored on Donn Clendenon’s homer, getting the Mets back in the game. And then, in the top of the ninth, he gently coaxed Davey Johnson’s fly ball into his glove, making the Mets the world champions.

In 1970, Jones had another solid year, hitting .277. He followed that with his second .300 season, hitting .319 in 1971. After that, injuries hindered him considerably. In 1972, he was limited to 106 games and hit only .245. In 1973, he helped the Mets to the seventh game of the World Series by hitting .260 but played only 92 regular season games. The carom found him in the famous “Ball on the Wall” game that helped the Mets turn the corner and he batted .300 in the NLCS victory over the favored Reds. He hit .286 in the World Series loss to the A’s and homered during New York’s 12-inning win in Game Two.

Jones had a resurgence in 1974, hitting .282 with 13 home runs, but he only played in 124 games. His Mets career came to an unexpected end in 1975, batting .240 with only one extra base hit and two RBIs in 21 games. It was an abrupt and bitter finish to what was the greatest offensive career by any Met to that time.

In addition to the wonderful moments mentioned earlier, Cleon Jones is also remembered for some less pleasant moments.

On July 30, 1969, Cleon was in a battle with Matty Alou for the league lead in batting and the Mets a factor in a pennant race for the first time in their history. In the second game of a soggy doubleheader in Shea Stadium, the Astros’ Johnny Edwards hit a ball to left field. Jones did not go after the ball particularly quickly due to the rain and some hamstring problems. Gil Hodges liked neither the slow run to the ball nor the weak throw that allowed Edwards to get a double. Hodges started walking out of the dugout. He went past the mound, past shortstop Bud Harrelson, and out into left field. Jones tells the story: “He said, ‘If you’re not running good, why don’t you just come out of the ball game?’ Then he turned around and headed toward the dugout. I knew he had something more than my leg in mind, and I followed him in.”

The manager pulling a league-leading hitter for not hustling made it clear that the Mets were no longer league doormats. Interestingly, years later, Hodges’ widow, Joan, said that the incident was less intentional than it seemed. Regarding going out to get Jones, she quoted Gil as saying “I never realized it until I passed the mound and I couldn’t turn back.”

The end of Cleon’s Mets career came in 1975 following a couple of unpleasant incidents.

Jones was left in Florida at the end of spring training in order to rehabilitate his knee following surgery. On May 4, police found him in the back of a van with a woman. He and the woman were charged with indecent exposure. Though he was never prosecuted, the Mets made sure to punish him. They ordered him back to New York to attend a press conference where he was made to apologize, with his wife, Angela, at his side. The public humiliation caused by the way M. Donald Grant handled the situation seemed to really hurt Jones.

Two months later, on July 18 in New York, manager Yogi Berra had Jones pinch-hit for Ed Kranepool. He lined out to shortstop. At the beginning of the next inning, Jones refused to go out to play the field. According to The Sporting News, “There was a shouting match between [Jones and Berra] on the bench and ended with Jones flinging his glove down, pulling towels off the rack and storming up the runway to the clubhouse.” Berra called it “the most embarrassing thing that’s happened to me since I became a manager.” Berra told the Mets it was “him or me” and the Mets immediately started trying to trade Jones. Finally, on July 27, after a trade to the Angels fell through, Jones was released. There were no winners in this situation. Berra, who’d been with the Mets since he’d been hired as a player-coach in 1965, was fired shortly thereafter. Jones and Berra had been in Mets uniforms longer than anyone other than Ed Kranepool.

Jones signed with the White Sox in 1976. His tenure there was less than four weeks. He got into a dozen games, batting just .200 before he was released again. His major-league career was over.

While in the minor leagues, Jones married his wife, Angela, who is a second cousin to Hall of Famer Billy Williams. They have two children, Anja and Cleon, Jr. Jones did a bit of big-league coaching, and he worked with the young Darryl Strawberry. But major league coaching jobs were not as available as Jones would have liked. He coached for a time at Bishop State Community College in Mobile, working with both the women’s softball team and the men’s baseball team. He ran a fast-food business for a while, though it was not successful. He worked for a maintenance company and then spent a number of years doing community service work in Mobile. “I work for the city, work with kids, work with the elderly. I enjoy it,” he told Maury Allen.

No offensive player was more important to the Mets in their first dozen years than Cleon Jones. When Jones left the Mets, he ranked as the leader in many career statistical categories. He was first in extra base hits, hits, RBIs, times reaching base, runs, singles, total bases, and home runs. He was second in at-bats, average (for rate statistics, minimum 1,500 plate appearances), doubles, games, hit by pitches, plate appearances, sacrifice flies, and triples. He was third in OPS and stolen bases, fourth in intentional walks, on-base percentage, slugging average, and walks, and sixth in home run percentage.

Even the passage of half a century has not erased Jones’s influence on Mets history. He still ranks in the top 10 in hit by pitches, hits, singles, at-bats, plate appearances, sacrifice flies, games, doubles, triples, extra-base hits, times reaching base, runs, RBIs, and total bases. His 1969 production still ranks high on the all-time season highs. His .340 batting average remained unchallenged for 30 seasons until John Olerud topped it at .354 in 1998.

It is unlikely anyone will argue Cleon Jones is the best player in New York Mets history. But there is little doubt that he is one of the most important. He was inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame in 1991, the sixth player inducted. He took part in the 2008 closing ceremonies at Shea Stadium, the place he brought to bedlam with his bow in left field in 1969.

Rather than sit around between golf games in his retirement, Jones and his wife Angela are giving back to “Africatown,” the community in Mobile where he had originally been raised. He had returned there in 1976 and found a decaying community that had shrunk to about 2,000 people—one-fifth the size it had been in his youth. The two of them leave the house by 8 A.M. each morning and set to work cleaning up and improving both public spaces and private houses. They clear lots and help restore houses for older citizens, sometimes building new houses. He’s received both city money and private donations, relying on willing volunteers but supervising projects himself. “We made it a priority as a family to spearhead this,” he said in December 2018, “and to get up every morning and make sure that we helped a neighbor. We go to bed with a plan to get up and work till dark to make somebody’s life worthwhile. We embarked on trying to make a difference.”1

Angela ribs him: “Old man, you need to sit down sometimes and rest.” He laughs in response, and says, “You know what? I have the energy. My energy comes from my desire to do it. Because when I go to bed at night, my mind is focused on what I have to get up and do that morning. It energizes me.” He added, “If you think receiving awards makes you happy, just think about giving something to someone who’s really, really in need, how happy that makes them. They’ll drive by your house and put a card in your mailbox, thanking [you], They’ll come up to you, stop your wife. That’s where I get my joy from, is knowing that we’ve been able to make a different in somebody’s life.”2

Last revised: July 1, 2021

SOURCES

108 Magazine

Allen, Maury. After the Miracle (New York: St. Martins Paperbacks, 1991).

Jones, Cleon with Hershey, Ed. The Life Story of the One and Only Cleon (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1970).

New York Times

‘The Sporting News

Lee Sinins’ Complete Baseball Encyclopedia.

NOTES

1 Anthony DiComo, “At 76, This Former Met Is Restoring His Home Town,” MLB.com, December 21, 2018. https://www.mlb.com/news/former-met-cleon-jones-makes-mark-on-hometown-c302127914

2 DiComo.

Full Name

Cleon Joseph Jones

Born

June 24, 1942 at Plateau, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.