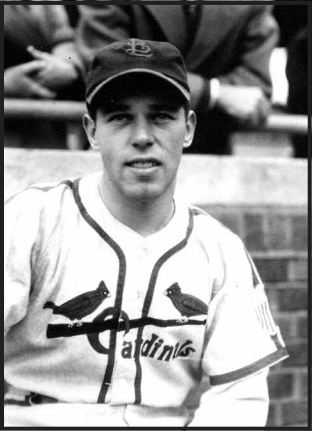

Stan Partenheimer

The date was May 27, 1944, and as left-handed starter Stan Partenheimer toed the mound and prepared to deliver his first major-league pitch, he might have paused for a moment to consider his surroundings.

The date was May 27, 1944, and as left-handed starter Stan Partenheimer toed the mound and prepared to deliver his first major-league pitch, he might have paused for a moment to consider his surroundings.

Only 1,408 fans dotted the stands of St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park that Saturday afternoon, as Partenheimer’s fifth-place Red Sox faced the eventual American League champion Browns in the finale of a four-game series. It might be expected that Partenheimer, only five days removed from the Red Sox Triple-A farm club at Louisville, would be experiencing a normal degree of first-game anxiety. But with future Hall of Famers Joe Cronin at first base and Bobby Doerr at second, he was assured of strong veteran leadership should he find himself in trouble. Which he immediately did.

Partenheimer walked leadoff batter Don Gutteridge, who quickly scored when Mike Kreevich tripled to center field. After surviving the balance of the inning, the rookie Red Sox pitcher surrendered back-to-back singles to start the second and was lifted by manager Cronin, ending his career as a member of the Boston Red Sox.

It is likely that few in attendance that day might have imagined that Partenheimer, like Cronin and Doerr, would also find himself a Hall of Famer some day. But while the august halls of Cooperstown generally await only those players whose careers are defined by statistical excellence, Partenheimer would eventually find himself in a different Hall of Fame, where success is measured not by the number of games won, but rather by the number and extent of lives influenced.

Originally founded in 1838, Sewickley Academy is nestled along the Ohio River 12 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, tucked below the wooded foothills that climb to the Allegheny Plateau. It was to here that Partenheimer, a decade removed from professional ball, traveled in 1957. And it was here, while serving for 28 years as boys’ athletic director, that he left his mark.

He was joined at Sewickley in 1963 by Jim Cavalier, who was hired to transform the country day school for pre-high-school students into a college-preparatory academy dedicated to academic excellence and personal enrichment.

“Stan was one of the finest men I ever met,” said Cavalier, who at 87 still lived in Sewickley in 2014 and avidly rooted for the Pirates. “Stan was like the Rock of Gibraltar. It amazes me how well, how seamlessly, we worked together.”

Working together is something they did for 22 years, with Cavalier holding the reins as head of the senior school (grades 9-12), and Partenheimer in charge of boys’ athletics.

“We started out on the right foot,” recalled Cavalier. “I knew it was good from the start. For a guy in his position, Stan was an incredibly patient man. He was level all the time. I always admired his absolute cool. Working with him was indeed a pleasure.”

Cavalier remembered Partenheimer as extremely fair and excellent working with parents. “We started playing lacrosse when there was no one playing it in Western Pennsylvania. He was very open and absolutely liked the idea that lacrosse took the place of football for us, which satisfied some of the parents.”

“He was one of the absolute best guys, especially with the students,” Cavalier continued. “He was an iron fist in a gloved hand. He had the rules and the kids knew the ruler. He had that kind of respect from the kids. If he had to raise his voice, they knew they were wrong.

“What stands out is how good he could be while being so even-tempered and in control. He was the most genuine guy. He was admired by everyone, and people knew what he stood for. With Stan, what you saw was what you got.”1

What you got in Partenheimer was the second son of a former major leaguer, born Stanwood W. Partenheimer on October 21, 1922. His father Harold P. (Steve) Partenheimer, was an Amherst College graduate who had played one game for the Detroit Tigers in 1913. His father had met his mother, Mary Stanwood, while playing summer ball in Maine. Mary was the daughter of Dr. Albert and Ellen Stanwood, the youngest child of an ardent baseball family that featured a brother, Harold, as captain of the Bowdoin nine and another brother, Joe, as captain at the University of Maine.2

Partenheimer was born in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, but like his older brother Hal, would develop as an athlete while living in Akron, Ohio, where his father worked as a tire-industry executive. Hal was an exceptional ballplayer, who would follow his father’s lead and star at Amherst. He later signed with the Cubs and hit .312 for Zanesville in the Middle Atlantic League in 1941 before going into the military in World War II.

Meanwhile, Stan was also making a name for himself. He received mention (as did future big leaguer Gene Woodling) in an April 1939 Cleveland Plain Dealer review of Akron High School baseball teams, and was selected to play as an outfielder in the league all-star game. That summer he compiled a 10-1 record for the Akron Killian Celtics, one of the strongest amateur teams in Ohio. Back at Buchtel High School in 1940, after previously lettering as a shortstop and first baseman,3 he pitched a pair of one-hitters and recorded a flurry of strikeouts tht introduced him to the local spotlight in 1940 as he led his team to the league championship. The April 1941 Plain Dealer baseball review announced that “Coach Chuck Kinney of Buchtel has four letter men, including Stan Partenheimer, southpaw, who attracted attention from major league scouts by turning in a brilliantly pitched game for the Akron Killian Celtics in the National Baseball Federation tournament last fall.”4 Also receiving a nod at South High was a returning letterman pitcher and future Notre Dame football coach, Ara Parseghian.

What the review did not mention was significant. In September 1940 Partenheimer was crossing campus while trying to catch a football when he collided with a bicycle. He suffered fractured bones in his right leg, and with gangrene setting in, narrowly avoided amputation. He was hospitalized for three months.5

As Partenheimer recalled, “I had three operations on my leg and the doctors said there was a chance that I could never run again, for I might have a stiff leg. The doctors were wrong, thank God.

“During my senior year in high school, however, I went to school exactly five days. The principal let me take my exams along with those of my class and I came out of the mess with an 86 final average for the semester.”6

The Canton Repository reported on his progress on April 30, 1941. “Tabbed as a real professional baseball prospect before he suffered a fractured leg last fall, Stan Partenheimer is again setting a fast pace as a pitcher for Akron Buchtel High School. A star basketball player in 1939-40, Partenheimer was injured in a sideline collision while watching a semipro football game. The leg didn’t knit properly and he was unable to play basketball until the district tournament, when he appeared in two games despite the fact he still had a noticeable limp.” On his return, Partenheimer received what was reported as the “greatest ovation ever given to a player of this school.”7

On the diamond, it was initially hard to see that the injury had slowed Partenheimer. He won his first game of the year and it was reported that “Young Partenheimer, showing no ill effects of the leg break which threatened to ruin his career last fall, allowed only four hits and had 15 strikeout victims.”8 He would eventually strike out 19 twice and turn in consecutive no-hitters while compiling a 6-1 record. But things were not quite the same.

More than 70 years later, Partenheimer’s oldest son, Steve, said, “He healed up, but before the injury he threw a heavy ball. I’m not sure what foot it was, but he was a southpaw and the injury caused him to lose some speed. As a result, he developed some other pitches. He had a fastball, a great curve, a screwball and knuckler. He also developed a submarine pitch so he had a lot going for him despite losing his speed. He had the same motion no matter which pitch he threw except for the submarine pitch.”9

His high-school career over, Partenheimer continued to walk with a limp. Despite medical opinions that he would never be able to compete as before, he maintained his desire to pitch in the majors.10 Shortly before departing with his brother Hal for Boston, from where Red Sox farm director (and future Hall of Famer) Herb Pennock had offered both a tryout,11 he pitched a three-hit shutout with 19 strikeouts against the Erie Colored White Sox. It was reported, “The first game was all Partenheimer. The 18 year old blond southpaw, who looks and pitches enough like Bob Feller to pass for the Cleveland ace’s younger brother, yielded single hits in the first, third and fourth frames and then settled down to business.”12

Five major-league teams had expressed interest in signing Partenheimer.13 After failing to catch on with the Toledo Mud Hens, a St. Louis Browns farm club, he eventually signed with the Red Sox in 1942. Playing for the Canton Terriers of the Class-C Middle Atlantic League and later the Oneonta Indians of the Class-C Canadian-American League, he compiled a 15-5 record with a 2.45 earned-run average. At Oneonta, with the roster depleted to 11 players due to service and other obligations, he and righty Tom Fine led the Indians to the Can-Am championship, with Partenheimer winning the final in a brilliant five-hit shutout.

Partenheimer was slated to join the Louisville Colonels of the American Association, but as the 1943 season began, he found himself pitching for the College of Wooster in Ohio. Although he previously had graduated from the Mansfield Business and Training School,14 a conference ruling allowing any student to participate in sports regardless of previous experience had produced this opportunity.15 Soon he found himself pitching for Uncle Sam, and while at Fort Hayes, Ohio, compiled a 17-2 record. However, the effects of the leg injury persisted, and Partenheimer’s toes, tightly drawn up into his boots as a result of his injury, were rubbed raw when he marched for combat, and he was honorably discharged.16

After finally arriving at Louisville for the 1944 season, Partenheimer was promoted to the Red Sox following a 13-strikeout, 14-inning 1-0 loss to the Columbus Red Birds. Joe Wood, Jr., son of Red Sox legend Smoky Joe Wood, was optioned to Louisville to make room. Two weeks after his lone appearance with Boston, Partenheimer was traded to Columbus, a St. Louis Cardinals affiliate. He soon found himself the subject of a lengthy Sporting News column, which reviewed his career and made note that his recent win over Louisville gave him victories over every American Association club that year. He was named to the league all-star team by his manager, Nick Cullop, and blanked the league champion Milwaukee Brewers.17 He finished the season at 16-7 with a 3.26 earned-run average.

In 1945 Partenheimer went to spring training with the Cardinals in Cairo, Illinois. Winners of the 1944 World Series, the Cardinals had their own army of established pitchers and pitching prospects, among whom Partenheimer would have to fight for a job. But he survived the process and made his National League debut on May 2 with a perfect seventh inning against the Pirates at Forbes Field. Three days later he pitched a scoreless ninth against the Cubs, earning a start 10 days later against the Braves in Boston. There, in 4⅔ innings, he surrendered seven hits and seven walks while allowing four earned runs. He escaped with a no-decision, and two days later again started against the Braves. When Tommy Holmes walked after a leadoff single, manager Billy Southworth knew that Partenheimer didn’t have it.18 He was immediately relieved by Ken Burkhart, who promptly surrendered a three-run homer to Butch Nieman. The Cardinals eventually won the game, but Partenheimer’s ability to perform at the big-league level was in doubt.

He appeared in one more game, pitching two lackluster innings of relief on May 30, before being released to Columbus in early June. He spent his summer toiling for the Red Birds and later for the International League’s Rochester Red Wings.

The Cardinals, trailing the league-leading Cubs by 1½ games, recalled Partenheimer on September 2 and immediately threw him into battle when starter Ted Wilks ran into trouble in the first game of a September 3 doubleheader against the Pirates. Again, walks plagued Partenheimer, as he surrendered four along with two earned runs in 3⅓ innings. On September 6, with the Braves pounding the Cardinals 9-1, he retired the lone Boston batter he faced.

On September 11, with the Cardinals trailing the Giants 5-1, Partenheimer was sent out to pitch the top of the seventh inning. He walked the first batter, Johnny Rucker, who was sacrificed to second. He induced the great Mel Ott to fly out to center field, before retiring Danny Gardella on a grounder to the mound. The Cardinals would rally to win the game, but with his throw to first baseman Ray Sanders to end the seventh, Stan Partenheimer’s major-league career was done.

With the war over, returning players flooded training camps during the spring of 1946. In early April the Cardinals released Partenheimer, and after joining the Browns’ organization, he found himself dropped from their Toledo farm club to their Eastern League affiliate, the Elmira Pioneers. In midseason he tumbled another level to Springfield (Illinois) team in the newly reformed Three-I League, where the “chunky portsider”19 finished his professional career in 1947 with an 18-8 record.

As early as 1944, Partenheimer had expressed an interest in physical conditioning, and he attended the Physical Education College of Ohio State University.20 It was a pivotal decision, as it was there that Partenheimer found his vocation, as well as his future wife, Dorothy “Dot” Johnson, whom he married in 1948. Soon the children arrived; Steve first in 1950, followed in three-year intervals by Kimwood, Hal, and Debra.

The May 3, 1950, Sporting News noted that “Stan Partenheimer, former pitcher owned by the Red Sox and Cardinals, has been appointed baseball coach at Kiski Prep, Saltsburg, Pa. He will also serve as assistant coach in other sports and as an instructor in mathematics. He has been coaching baseball and serving as a member of the faculty at Hilliards High School near Columbus, Ohio.”

And thus the die was cast. After a stint at the Valley School of Ligonier, Partenheimer took his growing family to Sewickley Academy in 1957, and it was there that he made his home and built his legacy. He and Dot lived on Faculty Circle at the Academy, where their children played and grew to adulthood.

Son Steve remembered the joy of growing up on campus, with long summers filled with play and fun. He recalled, “My father was the salt of the earth, one of the most fair-minded people. He was very patient with kids, but had higher expectations for his own children. He was the epitome of what you wanted an athletic director and coach to be.”

Partenheimer was not one to dwell on the past, and it was left to others to remind the world of his baseball success. According to Steve, “Hearing stories from my uncle, he couldn’t be beat when he was younger. He and my uncle played on the same teams and he was a star from the get-go. He could do anything. He even played soccer and held his own into his 50s.

“Everything was fluid, no matter what he did,” continued Steve. “Swimming, tennis, it was all the same. The only time he talked about his time in the majors was if you asked him. Usually it was only if Uncle Hal and the cousins were around.”

“He hardly ever talked about his own career,” agreed Cavalier. “We’d talk about the Pirates, but at times he would indicate what a thrill it was to have played in the majors.”

In 1959 The Sporting News remembered Partenheimer him in a story that noted, “The rare combination of a father and two sons, all three of whom played in organized baseball, visited the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum on May 15,” before detailing the playing careers of Partenheimer, his father, and his brother.

During the 1960s the gently aging lefty had the opportunity to prove he could still pitch. He and Dizzy Trout provided the backbone of a pitching staff of Pittsburgh area old-timers in annual exhibitions against the local media. Constantly pitching batting practice at the academy had kept his arm in shape. Nonetheless, he was reluctant to display his best “stuff” for fear of hitting opposing batters.21

Meanwhile, the first class of the Senior School had arrived in the fall of 1963 at Sewickley, and as time passed and the school grew, a new need emerged.

“We were new in sports, and the schools around us all had jerseys hanging up on the gym walls,” said Cavalier. “I’m not sure who started it, but there was a movement to honor our top athletes and to get some tradition into our school. We had soccer, basketball and baseball and later lacrosse came along.”

The result of this movement was the creation of a Sewickley Academy Sports Hall of Fame. Located on campus in a large lobby named for Partenheimer that leads to the men’s gymnasium, its first inductee was Stan’s son Steve, who was joined there by his brother Hal (a future professional soccer player), and, of course, their father. The Hall of Fame criteria requires that “All inductees must exemplify the best qualities of character and sportsmanship in accordance with the enduring principles of Sewickley Academy.” In selecting Stan Partenheimer for inclusion, it would appear the committee got things right.

Later, Partenheimer, his father and brother were inducted into the Greater Akron Baseball Hall of Fame. There they were recognized with other area greats such as George Sisler, and in time, Gene Woodling and Ara Parseghian.

Partenheimer retired in 1985 and was recognized at the Academy’s annual Memorial Day picnic. He was presented with two scrapbooks of letters and notes in which students, faculty, and friends shared the many ways in which he had touched their lives.

No longer able to live in their school-provided home, he and Dot followed son Steve to North Carolina. They purchased a small ranch house in Wilson and immediately established themselves within the community. It was there, while playing golf that Partenheimer first felt a twinge followed by numbness in his arm. A stress test revealed four blocked arteries, and despite a quadruple bypass, Partenheimer never fully recovered. He died on January 28, 1989. But he was not forgotten.

After his death, Sewickly established the Stanwood Partenheimer Memorial Scholarship. It is awarded each year to an incoming ninth grader who is “a promising athlete with good academic credentials and strong character.”

Dot died in 2004, and is buried with her husband at Evergreen Memorial Park in Wilson.

Sources

The author relied on information available from Baseball-Reference.com and Ancestry.com for this biography, as well as information from the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The author is grateful for the assistance of Susan Sour from the Alumni Relations office at Sewickley Academy; Jim Cavalier, former head of the Senior School at Sewickley; and in particular, Steve Partenheimer, son of Stan Partenheimer, who provided the subject’s scrapbook detailing his playing career from 1939-43.

Notes

1 Author interview with Jim Cavalier on September 8, 2014.

2 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook, 25.

3 The Sporting News, August 3, 1944.

4 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 20, 1941.

5 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook, 36.

6 Ibid.

7 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook, 7.

8 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook, 19.

9 Author interviews with Steve Partenheimer on July 20 and September 15, 2014.

10 The Sporting News, August 2, 1944.

11 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook, 24.

12 Ibid.

13 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook, 26.

14 Stan Partenheimer scrapbook 36.

15 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 2, 1943. He was scheduled to report to Louisville in Toledo on May 2. In the meantime, due to the ruling mentioned allowing any student to participate regardless of previous experience, he pitched for Wooster.

16 Author interview with Steve Partenheimer.

17 Canton Repository, July 26, 1944.

18 Boston Globe, May 18, 1945.

19 Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), May 3, 1947

20 The Sporting News, August 3, 1944.

21 Letter of Harold (Steve) Partenheimer to Lee Allen, February 20, 1968.

Full Name

Stanwood Wendell Partenheimer

Born

October 21, 1922 at Chicopee Falls, MA (USA)

Died

January 28, 1989 at Wilson, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.