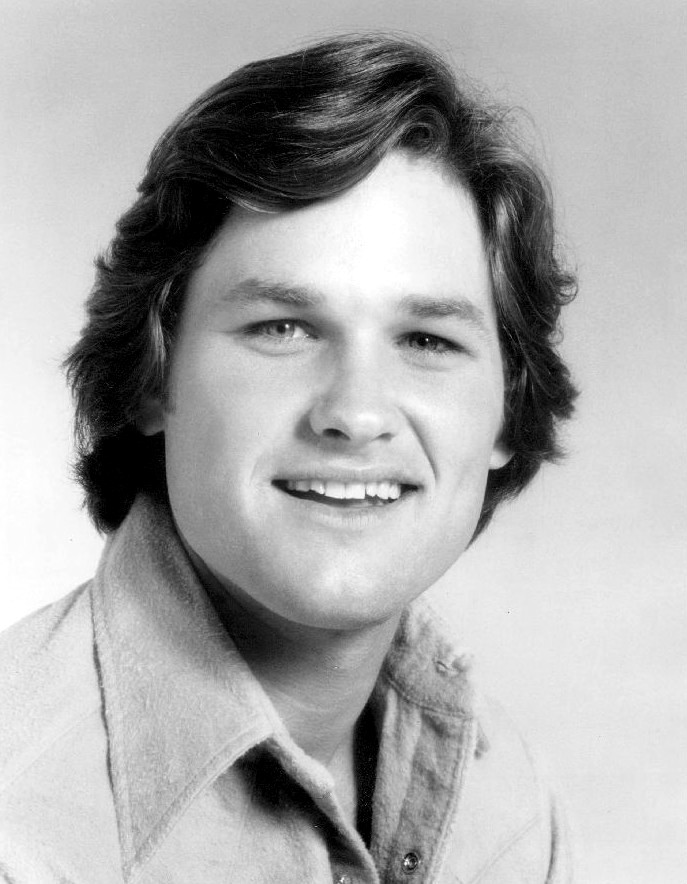

Kurt Russell

When Oregonians turned to the sports section of their newspapers on June 20, 1971, they got a shot of optimism for another year of Northwest League (Class A) baseball, set to begin that afternoon. An Associated Press story highlighted a switch-hitting Bend Rainbows prospect who gave hope for a climb past the team’s 1970 mark of 39-41. Rainbows General Manager Ward Goodrich “expects big things,” reported the AP article. The prospect was 20-year-old Kurt Russell.

When Oregonians turned to the sports section of their newspapers on June 20, 1971, they got a shot of optimism for another year of Northwest League (Class A) baseball, set to begin that afternoon. An Associated Press story highlighted a switch-hitting Bend Rainbows prospect who gave hope for a climb past the team’s 1970 mark of 39-41. Rainbows General Manager Ward Goodrich “expects big things,” reported the AP article. The prospect was 20-year-old Kurt Russell.

Yes, that Kurt Russell.

“I was playing in Mexico when there was an opportunity to play for a Triple-A ball club in Mexico City,” says Russell. “But the Rainbows picked me. I had to decide whether to go to Mexico City or go back into the U.S. system.”1

Had it not been for an injury, the movie star might have been under stadium lights instead of klieg lights for longer than his three-year tenure in the minor leagues. His skills prompted buzz about heading to the majors. The second baseman was already a popular-culture icon through starring roles in a string of Disney movies, the title role in the TV series The Travels of Jamie McPheeters, and several guest appearances on the prime-time TV circuit — Gilligan’s Island,2 Sam Benedict,3 The Man From U.N.C.L.E.,4 Lost in Space,5 and The FBI6 are samples of his work.

His career choices were, perhaps, a result of destiny — he was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on St. Patrick’s Day, 1951, to former minor-league ballplayer Neil Oliver “Bing” Russell and Louise Julia (Crone) Russell, a dancer. It was a full house with three sisters — Jill, Jamie, and Jody. Jill passed down the baseball gene to her son, Matt Franco, a major-league first baseman from 1995-2003.

Bing Russell played two seasons (1948-1949) for the Carrollton Hornets in the Class D Georgia-Alabama League and later made instructional videos and detailed questionnaires used by managers at all levels — including three-time World Series champion helmsman Sparky Anderson. Like his son, Bing Russell was an actor with formidable credits in films and guest-starring roles in television, including a recurring part as Sheriff Clem Foster for nearly 60 episodes on Bonanza.

“An outstanding memory is growing up in a baseball family,” says Kurt Russell. “My dad and I talked about baseball all the time, especially hitting. It wasn’t just a pastime in our house. It was the family business. He was a knowledgeable baseball man with a good combination of technical knowledge for different situations and different hitting styles. Because of my physicality when I was a teenager, he taught me to move runners and not make outs. That was my job. As a teenager, I had a long way to go physically. I could hit the ball in the gap and I had better than average speed and tremendous bat control. I also knew how to drag bunt effectively and sacrifice.”7

Like millions of Baby Boomers, Russell used The Science of Hitting by Ted Williams as his talisman. “From the time I was 10, I absorbed it,” recalls Russell. “I still can see that chart about hitting. It’s the basis of where I started as a kid and it stayed with me through my teens. As I developed into a more physical player, I adjusted my hitting style. When I got into my 20s, I was starting to hit the ball out of the ballpark because of pitch selection.

“We had a batting cage in the backyard from the time I was 12. It was 55 feet from a pitching machine that threw balls at 105 miles an hour. So after I was 16, the fastball didn’t mean much to me except the way the ball moved. The machine could also throw a cutter. Using it taught me to wait on the ball. My dad would hire pitchers to throw to me when I was a kid and a teenager.”8

Russell played semipro baseball, beginning when he was 15. But there was a bit of subterfuge required. “I wanted to get as many games under my belt as I could. In high school, I was playing in three different leagues, which was against the rules. I used different names to avoid detection.”9

His baseball knowledge deepened because of a family connection to a future Hall of Famer. Russell’s grandfather, Bud, a daredevil pilot in Florida and “six-time national stunt champion,” met Lefty Gomez in 1936, during the Yankees’ spring training in St. Petersburg, when the legendary pitcher wanted to take flying lessons. “In late February, Bing noticed a tall, skinny guy hanging around as well, chatting with his father while Bud worked on the engine of a Stinson Gullwing,” wrote Vernona Gomez, Lefty’s daughter, with Lawrence Goldstone in the 2012 biography Lefty: An American Odyssey. “When the skinny guy heard that Bing liked baseball, he showed up the next day with a dozen new American League baseballs in a box. Until then, Bud hadn’t asked who the stranger was.”10

A strong bond between the Yankees icon and the Russell clan developed; Lefty Gomez was like a godfather to Bing.

“Lefty would tell me stories about Williams,” says Russell. “My dad gave me technical knowledge. So, hearing about baseball from them and other players gave me a strong appreciation from an early age. After high school, the Twins and Giants talked about drafting me, but there was a question whether I could go to spring training if I was working. The Yankees also had some interest because of Lefty’s connection to the team.”11

The switch-hitting second baseman with a substantial show-business resumé fulfilled Goodrich’s expectations at Bend — 51 games, .285 batting average, All-Star team.

Russell’s Hollywood obligations did not interfere with baseball because he didn’t work from the middle of February through August. But it was not unusual for players to have secondary jobs for supplementary — or, on occasion, primary — income when the season ended. “My picture commitments at Disney now revolve around my ball playing,” said Russell in 1972. “I’m really lucky to have so much freedom in my filming schedule.”12 But there were opportunities lost, including a sitcom titled 38th Floor, set in the business world, with compensation reportedly between $130,000 and $180,000.13 It didn’t matter. The shooting schedule was set for summer and Russell chose the baseball diamond over the soundstage. “They said, ‘Well, I’m sure you’ll change your mind.’ They don’t understand. They think I’m using baseball as a device for more money or something. But this is my chance to play ball. The decisions are coming pretty easy right now.”14

In addition to baseball and acting, Russell has a pilot’s license. His service in the California Air National Guard’s 146th Tactical Airlift Wing from 1969 to 1975 overlapped his ballplaying career. Even though he was a Hollywood star, being salaried for the National Pastime held a special place. “I must say the first time I got my check from Bend, I felt real proud. I felt I had done something. I was playing baseball for a living, something I’d always wanted to do.”15

Russell went to spring training with the Hawaii Islanders in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League and played for the Walla Walla Islanders in the Northwest League in 1972. A month into the season, he broke his ankle when he was taken out in a double play. The injury sidelined him for three and a half weeks. Then he played three weeks while he healed.16 His playing opportunities dropped to 29 games, but his batting average improved 40 points, to .325. Russell acknowledged that his year at Bend was a learning opportunity for dealing with slumps, with his father diagnosing the problem — going after low pitches. He had a keen interest in trying to hit the low curveball.

After adjusting, his strikeout ratio dropped like a brick in a pond — in his last 17 games, he struck out once. On defense, Russell’s forte was turning the double play. But his performance suffered — 22 errors in 49 games — because of a glove that he used to “make things quicker.”17 At the time, Russell acknowledged the glove’s size as a problem: “I used a real small Wilson glove, probably, the smallest made. I thought it would be good for the double play, but I had a lot of trouble with it.”18

Actors dream of winning an Academy Award. But Russell had his sights set on honing his baseball skills to get into the major leagues. “Achieving awards in acting doesn’t appeal to me,” said Russell. “I don’t know why. But achieving awards in baseball appeals to me a lot. I’d love to win most valuable player in any league or win the batting title or be the premier fielder in the league.”19

For spring training in 1973, Russell again went to the Hawaii Islanders. He wound up with the Chicago White Sox for 24 hours in a three-way trade before getting sent to the El Paso Sun Kings — a Double-A team in the California Angels organization — for 1973. Russell’s father owned one-third of the team.20

In his first game, he notched an RBI, scored a run, and made a double play on defense.21 It seemed like the start of something big for the 5’11”, 170-pound Russell, who smacked the horsehide all over Texas League ball fields — in six games, he had a .563 average. But a torn rotator cuff led him from the starting lineup to the 10-day disabled list and the office of Angels orthopedist Dr. Robert Kerlan.22 Less than a week later, Russell’s DL time got extended to eight weeks.23 A day after that announcement, the Sun Kings gave him an unconditional release.24 “I’m not discouraged about baseball,” said Russell. “I’ve had a good arm all my life. I just hope I haven’t ruined it.”25

Russell’s baseball days weren’t over yet.

The Portland Mavericks signed Russell in mid-July;26 he played 23 games and hit .229. His father was his boss — Bing Russell founded the Mavericks, the only minor-league team unaffiliated with Major League Baseball at the time. “I went to help my dad,” explains Russell. “I had the release so I could work out with the club. If I healed, I could play.”27

The Portland Mavericks signed Russell in mid-July;26 he played 23 games and hit .229. His father was his boss — Bing Russell founded the Mavericks, the only minor-league team unaffiliated with Major League Baseball at the time. “I went to help my dad,” explains Russell. “I had the release so I could work out with the club. If I healed, I could play.”27

Passion, not profit, was the reason for the elder Russell’s venture. Speculation about nepotism was unfounded; the Russell clan cared too much about baseball to let emotions overshadow judgment. “But the night I watched him in Dudley Field bang out those three doubles and that long homerun [sic] over the trees in right-center was as great a thrill as I have ever had,” said Bing Russell. “I’ll guarantee you it was worth any amount of money this club might ever lose.”28

A formidable influence was Mavericks manager Hank Robinson, whom Russell praises as “a primary mentor, terrific baseball man, and great hitting instructor. Just being around him, you absorbed baseball osmotically. His personality, approach, and demeanor on and off the field invaded you. Many guys who worked with Hank felt that way.”29 After the 1973 season, Russell ended his professional baseball career. Or so it seemed.

The 2014 documentary The Battered Bastards of Baseball, produced by two of Bing Russell’s grandsons, chronicles the journey of the Mavericks, a team consisting of eager rookies, seasoned players who never quite reached their potential, and veterans on the brink of retiring but wanting one last chance to play baseball and get paid for it. Kurt Russell was in the third group — he suited up for one game with the Mavericks in 1977.30

“I was there for four or five weeks. I did my dad a favor because he sensed it might be the last season for the team. A sportswriter called me and said, ‘Your dad won’t ask, but I will.’ I was playing on a soccer and rugby team in Aspen.”31 Indeed, it was the team’s last season. When the Pacific Coast League tried to muscle into Portland, it needed the territorial rights controlled by the Mavericks; arbitration resulted in a $206,000 payment to Bing Russell and the team’s disbanding.

“One of the things that excited me was getting higher in the leagues because the lights were better,” says Russell. “The pitching quality worked to my advantage because the pitchers were not as erratic in the higher leagues. My favorite part was that I only had one responsibility — to be at the ballpark. It was fun and relaxed. People are paying to watch you play. I think that’s what gets you through the rougher time. It took me a few years to get used to not being a ballplayer. But I was lucky that I had another career to go to.”32

Russell’s athleticism gives him terrific insight to physicality, an invaluable asset for actors. Where his peers often play different levels of a character type, Russell has a résumé spanning several genres — thriller, romantic comedy, action, biography, western, science fiction — demanding a highly significant level of physical dexterity, ability, and knowledge.

Watching Russell’s performances will reveal a variety of movements that have become hallmarks of his movies: carrying 50-60 pounds of firefighting gear while running into burning buildings in Backdraft; ambling with the authority of a veteran Hollywood stunt coordinator in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood; throwing his right arm around a customer in a “hail fellow well met” manner and talking as fast as he used to run on the base paths to sell a clunker in Used Cars; fighting a hand-to-hand death-match against a terrorist as part of his mission to rescue the President of the United States in Escape from New York; helping foil a terrorist hijacking and landing a jetliner with the experience of flying lessons and one solo flight in a small plane in Executive Decision; fighting, escaping, and outwitting henchmen across Los Angeles with Sylvester Stallone to catch a mobster in Tango & Cash; staring down the Clantons in Tombstone; capturing the steely determination in movement and speech of 1980 U.S. Winter Olympics hockey team coach Herb Brooks in Miracle; and quarterbacking his former high-school football team in his mid-30s for a rematch against its rival in The Best of Times.

While promoting Tango & Cash on The Oprah Winfrey Show, co-star Sylvester Stallone praised Russell’s athletic ability for picking up polo.33 That sport entails terrific risks. “It’s like trying to play golf during an earthquake,” explained Stallone.34 On the first day of filming Tango & Cash, Russell tore a hamstring during the third take of a foot-chase scene. It was just the beginning of physical maladies that he endured for the buddy-cop comedy while pushing 40.35 Even though he admitted to not really working out, the ability to bounce back from or play through injury is an athlete’s credo.

Russell’s knowledge of body movement informed what has probably been his most scrutinized performance — Elvis, a three-hour TV movie that aired on February 11, 1979, a year and a half after Elvis Presley’s death in 1977; his father played Elvis’s father, Vernon Presley. With Elvis’s demise still resonating in the American consciousness, this ABC broadcast directed by John Carpenter had to battle the audience’s preconceptions of an iconic figure that had been omnipresent in popular culture for more than 20 years. Russell put forth a depiction of humanity, desperation, and fame requiring him to not only portray Elvis’s on-stage gyrations accurately, but also convey the off-stage emotions through body movement.

“The production’s chief asset is the performance of Kurt Russell in the lead role,” wrote John J. O’Connor in The New York Times. “I have only seen this actor in television’s ‘Swiss Family Robinson’ series and a couple of westerns, and was totally unprepared for his dynamic capturing of the Elvis image. He is probably better looking and less pudgy than the original, but his swagger and curious vulnerability are brilliantly on target. It is an impersonation that expands to a stunning performance.”36 (O’Connor’s analysis is factually wrong on Swiss Family Robinson — Russell did not appear in the 1975-76 ABC television series or the 1960 Disney film).

Elvis had a bit of circularity — in the 1964 movie It Happened at the World’s Fair, Russell had a small part requiring him to kick Elvis in the shins.

While filming the 1984 World War II-era romantic comedy Swing Shift, Russell and co-star Goldie Hawn escalated their on-screen affair to real life and, while never formally married, are one of the all-time Hollywood couples.37 Russell had been married to actress Season Hubley from 1979-1983 — they met during the filming of Elvis and had a son named Boston. Hawn had two children with musician Bill Hudson — Kate Hudson and Oliver Hudson, who followed in their mom’s footsteps as actors — but they have long considered Russell to be their father and describe him as such in interviews. Born in 1986, Russell and Hawn’s son, Wyatt, continued his family’s sports legacy — he played goaltender for professional hockey teams from 2003-2007 and 2009-2010.38 True to form, he’s also an actor.

Russell’s performance in Swing Shift has as much to do with athleticism and body movement as it does comedy timing and romantic chemistry. His character, Lucky Lockhart, is a motorcycle-riding, trumpet-playing, assembly-line supervising mechanic in an aircraft-manufacturing plant. It’s a role requiring different levels of physicality, which are unlocked because of the ability to combine natural athleticism with deep study into a character’s emotional, mental, and physical reactions.

His other co-starring role with Hawn is Overboard, a romantic comedy about a mismatched couple — Russell’s working-class carpenter to Hawn’s over-privileged heiress. After getting thrown overboard from her yacht to learn a lesson about manners, Hawn’s character suffers amnesia and falls for the guy who was once the target of her condescension.

Convinced that she’s his wife, the heiress-turned-pauper goes from living in luxury to suffering in squalor while raising four ragtag sons that she believes are hers. When she realizes the truth, her feelings have become so deep that she abandons her snooty ways — and parasitic husband — and gets the family she never knew she wanted. Beyond the dialogue, Russell suggests someone you would believe to be a carpenter — the way he holds a tool, carries equipment, or just walks towards something that needs to be fixed.

“As my acting career went on after baseball, I never said anything about the physicality,” reveals Russell. “But people picked up on it. I would always enhance the role and worked with stunt men to do it myself. If I couldn’t do it, they didn’t either. In longer shots, they would do it and then I would do it in a close-up. I think that was one of the quiet tools that I had in my toolbox. I always felt athletically superior, so it was an unspoken calling card for me. Many of my characters weren’t physically or specifically athletic, but they were doing something athletic. You have to get to a place of complete confidence and credibility.

“I can tell you from the way a guy walks on the field whether he’s left-handed or right-handed. Your eyes pick up things very quickly if watch closely because people have a rhythm in the way they move. I watched pitchers because I was going to be on first base and trying to steal. When I got parts after my baseball career, it was easy to pick up the movements of my characters and why they’re moving a certain way. ‘Bull’ (in Backdraft)has his nickname because he’s a bull in a china shop, just rushing into danger. An escape artist is more measured. He slithers in and out of things I rarely run in a movie the way I run in real life, which is like a ballplayer. You have to break down the part and look like an average Joe would move.”39

In the mid-2000s, Russell turned his passion for wines into a business — his sister Jamie runs the business side of GoGi Wines. Show business, sports, and harvesting wine grapes, are disciplines with the same indicators for success — consumers, critics, research, performance, and stamina. “What I learned in baseball was pacing,” says Russell. “You don’t get too high or too low. It’s a grind and you have to enjoy that it’s a grind. You learn to love it. In the creative world, you get so many chances. It’s not important that you get it right the first time. What matters is that you get it right one time. You have to get it right at that moment. The minute it happens, it’s electric.

“A movie set is a quieter world. Half the people don’t know what you’re trying to do. There’s a great sense of accomplishment, but it doesn’t come together until much later. In sports, you get that sense immediately, whether it’s knocking in a winning run or a tying run late in the game. There was no showboating. And when you fail, your teammates know how you feel.”40

Once a baseball guy, always a baseball guy: “I still look at the world through the eyes of a ballplayer. On a set, I want to make the team. If necessary, I’ll carry this team.”41

Last revised: January 2, 2020

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Kurt Russell for his telephone interview (February 27, 2019).

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David H. Lippman and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Find Kurt Russell’s career minor-league statistics at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Kurt Russell, telephone interview with David Krell, February 27, 2019 (hereafter Russell-Krell interview).

2 Gilligan’s Island, “Gilligan Meets Jungle Boy,” CBS, February 6, 1965.

3 Sam Benedict, “Seventeen Gypsies and a Sinner Named Charlie,” NBC, March 2, 1963.

4 The Man from U.N.C.L.E., “The Finny Foot Affair,” NBC, December 1, 1964.

5 Lost in Space, “The Challenge,: CBS, March 2, 1966.

6 The FBI, “The Tormentors,” ABC, April 10, 1966.

7 Russell-Krell interview.

8 Russell-Krell interview.

9 Russell-Krell interview.

10 Vernona Gomez and Lawrence Goldstone, Lefty: An American Odyssey (New York: Ballantine Books, 2012), 207.

11 Russell-Krell interview.

12 “Russell A Pro Athlete,” The Courier (Waterloo, Iowa), January 28, 1972: 29.

13 Ron Coons, “Onward to Walla Walla!,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), May 21, 1972: 58. 38th Floor is not mentioned on imdb.com, so it’s most likely a pilot that was taped but not sold.

14 Coons, “Onward to Walla Walla!”.

15 Coons, “Onward to Walla Walla!”..

16 Kurt Russell, telephone interview with writer.

17 Ibid.

18 Ron Coons, “Onward to Walla Walla!”

19 Betty Hopper, “Russell Combines Acting, Baseball,” Associated Press, Indiana Gazette, September 23, 1972: 28.

20 Peter Ciccarelli, “Bing Russell Says Kings To Be Back,” El Paso Herald-Post, August 13, 1973: 23.

21 “Russell Has Good Debut,” El Paso Herald-Post, April 17, 1973: 6.

22 Bill Cousins, “Grand Slam Hand Kings Victory,” El Paso Times, May 12, 1973: 23.

23 “E.P. Loses Russell 8 Weeks, “ El Paso Herald-Post, May 16, 1973: 43.

24 “Kurt Russell Given Release,” El Paso Times, May 17, 1973: 48.

25 “Kurt Russell Given Release.”

26 “Mavs activate Kurt Russell,” United Press International, Capital Journal, July 26, 1973: 23.

27 Russell-Krell interview.

28 Ciccarelli, “Bing Russell Says Kings To Be Back.”

29 Russell-Krell interview.

30 The Mavericks employed Ball Four writer Jim Bouton, who tried to make a comeback after a few years away from baseball. He had pitched for the Yankees, Pilots, and Astros. Another comeback in 1978 with the Braves resulted in five games and a 1-3 record. Oscar-nominated screenwriter Todd Field was the Mavericks bat boy.

31 Russell-Krell interview.

32 Russell-Krell interview.

33 The Oprah Winfrey Show, King World Syndication, December 4, 1989.

34 Oprah Winfrey Show, December 4, 1989.

35 Oprah Winfrey Show, December 4, 1989.

36 John J. O’Connor, “ABC Revisits Rock Era And a Troubled Presley,” The New York Times, February 9, 1979: C30.

37 Russell and Hawn had met nearly 20 years before Swing Shift, on the set of the 1966 Disney movie The One and Only, Genuine, Original Family Band.

38 Wyatt Russell played in the British Columbia Hockey League, United States Hockey League, Ontario Junior Hockey League, and the Eredivisie — a league in the Netherlands.

39 Russell-Krell interview.

40 Russell-Krell interview.

41 Russell-Krell interview.

Full Name

Kurt Vogel Russell

Born

March 17, 1951 at Springfield, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.