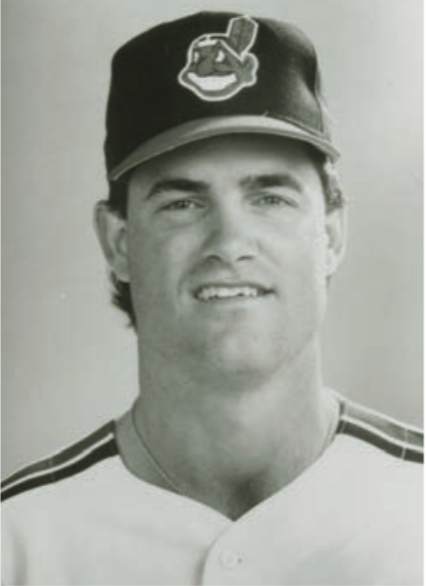

John Farrell

John Farrell began his professional baseball career as a right-handed pitcher with an 0-5 record for the 1984 Class-A Waterloo Indians in the Midwest League. He’d been drafted three times by that point, but it was certainly an inauspicious start to a career that saw him manage the 2013 Boston Red Sox to a world championship.

John Farrell began his professional baseball career as a right-handed pitcher with an 0-5 record for the 1984 Class-A Waterloo Indians in the Midwest League. He’d been drafted three times by that point, but it was certainly an inauspicious start to a career that saw him manage the 2013 Boston Red Sox to a world championship.

John Edward Farrell was born in Monmouth Beach, New Jersey, on August 4, 1962. He attended a regional high school that drew from four communities on that part of the Jersey Shore: Shore Regional High School in West Long Branch.

Farrell’s father, Tom, was a left-handed pitcher, also in the Indians system, in 1953-55. He didn’t advance far, but he talked baseball endlessly with John. Tom’s trade was masonry, but he became a commercial fisherman and John often went out on the boat with him. “A lobster fisherman, gillnetter. That’s what I thought my path was going to be.”1

Tom Farrell was a 6-foot-3 left-hander signed by the Cleveland Indians and initially assigned to Reading in 1953. He pitched for the Sherbrooke Indians in the Provincial League in 1954, with a losing record (9-12) but a good 2.90 earned-run average. He pitched briefly in 1955 as well, 1-0 in four games, but that concluded his career. He and his wife, Suzanne, had four daughters and two sons.

John’s brother played some baseball and ran track in high school, enlisted in the Air Force, and as of 2014 owned a roofing company in Dover, Delaware.

John was the ninth-round pick of Walt Jocketty and the Oakland A’s in 1980, out of high school. Farrell decided to go to college instead, and went to Oklahoma State. There he was also drafted, after his junior year, a 16th-round selection by the Cleveland Indians in 1983. He elected to play one more year with the Oklahoma State Cowboys, had continued success on the mound, and was rewarded with a second-round selection (again by Cleveland) in 1984. This time he signed and was assigned to Waterloo. The Indians’ signing scout was Red Gaskill, whom Farrell remembers as “a longtime scout that had an ease about him, who was willing to explain all that was involved, and what his view was and his evaluation. He almost befriended you and advised you a little bit along the way.”

Tom Farrell’s background had a lot to do with John’s interest in baseball. “There’s no doubt. In growing up south of New York City, Tom Seaver was in his prime with the Mets at the time and he was the TV prompt and teacher. My dad would break down his delivery when he was pitching on TV. That’s why his picture sits right there.” Farrell pointed to a framed photo of Seaver on his office wall at Fenway Park, one depicting Seaver in a Red Sox uniform. Tom Farrell died in 2003.

Playing in 1984 for the Maine Guides at Old Orchard Beach, Cleveland’s Triple-A club, was John’s second visit playing baseball in New England. He had spent the summer of 1982 in the Cape Cod League, playing high-level amateur ball for Hyannis. As Stan Grossfeld wrote in the summer of 2014, Farrell’s stay with his host family was memorable: “Farrell spent the nights on a rollaway cot in a backyard tool-shed apartment in Osterville with skunks as neighbors.”2

Farrell was on the varsity with Oklahoma State all four years, and the team made it to the College World Series all four years.

With the Guides, Farrell was 2-1. It was the only team he had a winning record with before he made the major leagues.

It wasn’t that Farrell had superb ERA’s and lacked only run support or better fielding behind him. His record was a little up-and-down:

1985 Waterbury Indians (Double-A Eastern League) 7-13 (5.19 ERA)

1986 Waterbury Indians (Double-A Eastern League) 9-10 (3.06 ERA)

1987 Buffalo Bisons (Triple-A American Association) 6-12 (5.83 ERA)

But he was learning to pitch. And in mid-August 1987, he got the opportunity every minor leaguer hopes for: He was called up to the big leagues.

Given his record at Buffalo, was Farrell a little surprised to get the call to the majors? “I got the call basically by attrition. Everybody else went down before me. I might have been the 21st pitcher that year. I was 6 and 12, I believe, before getting called up. I had been pitching well probably the four starts prior, with varying success throughout the year – mostly lack of success. But when I got to the big leagues, I felt like I was prepared, mentally as much as physically.”

John Farrell’s debut came on August 18, at Cleveland Stadium for manager Doc Edwards. The Indians were 45-73 at the time, in last place, 25 games behind the first-place Blue Jays, and they had indeed suffered significant staff attrition, most recently an injury to Sammy Stewart. The game with the Brewers was tied, 8-8, after 11 innings. Farrell was Cleveland’s fourth pitcher of the game; he worked the top of the 12th. “I had never thrown in relief in my life,” he recalled. “The first two pitches I threw were base hits. I threw two pitches and had men on first and second.”

Farrell gave up back-to-back singles to Paul Molitor and Robin Yount, but then induced Glenn Braggs to ground into a double play. He walked the next batter but another grounder got him out of the inning. The Indians loaded the bases, and a two-out single by Pat Tabler gave Farrell a win. “I’m in Cleveland all of six hours, throw 13-14 pitches, and get the victory. Imagine that,” he said.3

Farrell pitched in nine more games that year, all of them starts. His second game was a complete-game win over the Tigers. He shut out the Brewers for nine innings on three hits for his second start, but the Indians’ Doug Jones coughed up a run in the 10th and lost that one. In that game, Farrell had held Molitor hitless, snapping the hitter’s 39-game streak. Molitor signed a ball for him, “Wishing you a great career.” By season’s end, Farrell was 5-1 with a 3.39 ERA. He finally had a winning record, when it most counted. The Indians, however, finished in last place, 37 games behind.

Farrell was considered “one of the rising pitching stars of the major leagues.”4 Two more very solid seasons followed. He was 14-10 in 1988 (4.24) in 31 games, all but one a start. And, though with a losing record (9-14) in 1989, he had changed his delivery and pitched distinctly better (a 3.63 ERA), with 132 strikeouts against 71 walks. The team finished sixth both years, in the seven-team AL East. On May 4, 1989, Farrell took a no-hitter into the ninth inning against Kansas City, but an error and then a Kevin Seitzer single brought the tying run to the plate. Doug Jones came on in relief and got a double play with his first pitch, retiring the side with two more pitches. Farrell got credit for the 3-1 win.

In 1990 Farrell’s elbow finally gave out on him. He’d had recurring problems with it, on the 15-day DL as early as August 1998 with “right elbow tightness,”5 and that springtime it delayed his start a bit. He was removed during the June 24 game to have his elbow examined and he missed three months, only coming back in late September. He pitched to a 4-5 (4.28) record in 17 starts. He underwent exploratory surgery in October. He had a bone chip removed, repaired a torn ligament, and had his ulnar nerve relocated. How had Farrell kept going for the couple of years the elbow had been bothering him? “A blue-collar background,” he said. “Hard work is just something I grew up with, and maybe I just expected myself to keep going. Besides, I did have periods where the elbow didn’t bother me.”6

Farrell clearly needed even more tenacity. As it turned out, he needed a second operation in September 1991 – particularly frustrating in that he had just put in 11 months of rehabilitation work. “But there was no choice. There was no option. It had to be done again. I tore the ligament completely off the bone and they reattached it rather than transplanted. So I don’t think structurally the procedure would have worked, the way it unfolded. Unfortunately. Another 15-16 months of rehab and I came back and made the team with the Angels. Which I think was a little surprising to a lot of people.” He missed all of the 1991 and 1992 seasons. His right arm required two elbow reconstructions. And the Indians didn’t want to carry him on the roster anymore; he was released in November 1991.

The California Angels took a flyer on Farrell, signing him in early 1992, even though they knew he wouldn’t be able to pitch again until 1993. The Angels’ senior vice president for baseball operations, Dan O’Brien, said, “It might sound corny, but it’s true. If you can bet on a man’s character and ability, then you’ve got a good chance to succeed. He’s a bulldog with enormous character. I had faith in John, and John had faith in us.”7

When Farrell did pitch, it was a disappointment to all concerned. He started the season for the Angels, worked a stint (4-5, 3.99) for Vancouver in midseason, and then finished up with the Angels. His major-league stats were 3-12 with a 7.35 earned-run average. He pitched in three May 1994 games (1-2) but with an ERA of 9.00, the Angels had pretty much seen enough. Farrell pitched some again for Vancouver, but was released in early June. The Indians signed him again and assigned him to Charlotte. Even at Triple-A, he had a 5.61 ERA that year.

Had he tried to come back too soon? Or was it just that the elbow was unable to be reconstructed sufficiently well to pitch in top form at the major-league level? “I missed 2½ years and I lost probably 4-5 miles an hour.”

A more promising 1995 and in the beginning of 1996 with Buffalo led to some interest from the Detroit Tigers and a May 14 trade for minor-leaguer Greg Granger. It was the first of only two trades in Farrell’s career. The second came in October 2012, when he was manager of the Toronto Blue Jays and was traded to the Red Sox with David Carpenter for infielder Mike Aviles.

Farrell’s work in the big leagues in ’95 and ’96 was very brief. The Indians went to the World Series in 1995, but Farrell’s only big-league appearance was on September 17 at Jacobs Field. It was a battle of division leaders; the Red Sox were visiting. Dennis Martinez gave up two runs in the first inning and manager Mike Hargrove called on Farrell to pitch the second. He did, retiring the side in order. In fact, he pitched 4⅔ innings of relief but gave up four runs (only two of them earned). The Indians scored five runs in the bottom of the sixth, so Farrell was off the hook.

The Indians swept the Red Sox in the Division Series, beat Seattle in six in the ALCS, but then lost to Atlanta in six games during the World Series.

In 1996 Farrell went to spring training with the Seattle Mariners but was released in March. In April he signed with the Indians and a month later was traded to the Tigers. He pitched in two May games for the Tigers and took a loss in both. His final major-league stats were 36-46 (4.56, with a WHIP of 1.406).

The next year, 1997, Farrell returned to Oklahoma State and worked for five years in Stillwater as assistant coach and recruiting coordinator. He had a family to support – he’d become engaged before his senior year of college and married in the winter of 1984. He and his wife, Susan, raised three sons. At the time of the August 2014 interview, all three were still in the game. Jeremy, drafted by the Pirates in 2008, was in Double-A with the White Sox. Shane, drafted in 2011 by Toronto, was in the front office for the Cubs, after his own shoulder injury. The youngest, Luke, drafted by Kansas City in 2013, was in Double-A.

“I retired in ’96 at the All-Star Break. I needed 22 or 24 credits to finish my degree. We were living in southern Ohio at the time and I was commuting every weekend to Oklahoma back and forth, to finish my degree that semester. During that time I had talked to Mark [Shapiro of the Indians]. I was set to graduate in December and just didn’t know what my next step was going to be. He said, ‘You can go back to the minor leagues and you can be a pitching coach.’ I said, ‘You know, I just came out of the minor leagues.’ I wasn’t ready to go back in. He talked about the possibility of assistant farm director. I was unsure of that. So in the last month of school, Gary Ward stepped down from Oklahoma State and I approached the assistant, who looked like he was going to be named the head coach, and said, ‘If you’re looking for a pitching coach, I would love to talk to you about it.’ Well, that’s how it unfolded. I spent five years there.

“My path has been unusual. When I look back, there’s five-year cycles.”

All the while, Farrell maintained contact with Mark Shapiro and when Shapiro was set to take over as Cleveland’s GM from John Hart after the 2001 season, John called Mark and said he’d be interested if a position was open. He was ready to make a move. He left the Cowboys to join the Indians. Shapiro appointed him farm director (director of player development), It may have been a surprise to go outside Organized Baseball for such an important hire, but Shapiro said, “I trust John’s judgment implicitly, because he doesn’t do things haphazardly. He thinks them through. There’s a method to everything he does.”8

It was another five-year stint for Farrell, and many felt he was “on the GM track.”9 But he responded to a call from Boston Red Sox manager (and former Indians teammate) Terry Francona. The two had stayed in touch as well, and even had a conversation when Francona was manager of the Phillies, but that was probably for a minor-league position, and Farrell figured he’d stay put.

Now the time was right. The Red Sox hired Farrell as the major-league pitching coach, to begin with the 2007 season. Dave Wallace had been pitching coach through the 2004 World Series win and the two years that followed, but Boston elected not to renew Wallace’s contract. It was the first coaching position Farrell ever had, other than at Oklahoma State in 1997.10 “First time I was a pitching coach in pro baseball.” He was someone Francona really wanted. “This isn’t a thing where you start lining up friends and friendships,” Francona said. “What I wanted was someone who I thought could be an outstanding pitching coach for the Boston Red Sox.”11

One of Farrell’s first challenges was dealing with newly acquired Japanese star Daisuke Matsuzaka. Farrell even devoted some time in the springtime studying Japanese with a tutor.12 Aided as well by having superb catcher Jason Varitek behind the plate, “Dice-K” won 15 games his first year, and was 18-3 his second with a 2.90 ERA. Farrell’s staff posted a league-best 3.87 ERA in 2007 and in his first year with the Red Sox they reached the heights once more, finishing first in the AL East and sweeping the Angels in the Division Series. They then had to fight all seven games to beat the Indians in the ALCS (clearly overcoming a strong Cleveland team, most of whom had been developed or acquired during Farrell’s time there). The Red Sox swept the Colorado Rockies in the World Series.

“Fenway Park is an amazing place, a great place to work,” he said. “The fans are so passionate. You feed off their passion.”13 Farrell served as Red Sox pitching coach in 2008, 2009, and 2010, and the Francona/Farrell working relationship seemed to be an excellent one. Their work helped produce trips to postseason play in both 2008 and 2009.

The Toronto Blue Jays made Farrell their field manager starting in 2011. He led the team for two years, and two fourth-place finishes, but the Red Sox really wanted him back after their disastrous fifth-place finish in 2012. Francona’s contract had not been renewed after 2011 and Bobby Valentine had managed the Red Sox for the one season. After finishing last in the AL East, Valentine was let go. Farrell clearly wanted to come back to Boston, so Toronto chose not to stand in the way and a deal was effected, with the Blue Jays getting the very capable shortstop Mike Aviles in trade. And the 2013 Red Sox went from worst to first, winning it all. John Farrell was a world champion again, this time in his first year as field manager for the Red Sox.

It had been a lateral move, of course: major-league manager to major-league manager. Was there something about the city of Boston, or the organization, that maybe appealed to him? “All the above. All the above. Established relationships with Ben [Cherington], Mike Hazen, many others. There was a personal connection to the medical community here with our youngest son having to go through his own surgeries and radiation. There was a lot here. Plus, it always felt like a very unique place to me – whether that was coming in as a player back in the ’80s and early ’90s or having been here for the four years as pitching coach. It’s always felt like there’s been a connection here.”

The 2013 Red Sox were known as the “Band of Bearded Brothers” – as the NESN retrospective DVD proclaimed. The bombing of the Boston Marathon in April had brought the team, and the city, together in a special way, but most of the team had already begun to grow beards before that, forging a certain kind of bond between the players. Since Farrell had studied Japanese with his two pitchers from Japan, why had he not grown a beard in 2013? “I’ve never had one, and I wasn’t about to start.” And there are benefits to maintaining a degree of distance between manager and players. The team could hardly have been more successful in 2013, only out of first place for two weeks in May and four days in July, winning the ALDS in four games, the ALCS over the Tigers in six, and the World Series over the St. Louis Cardinals in six games – winning a World Series in front of a Boston home crowd for the first time since 1918.

Things went south in 2014, however, and the Red Sox struggled badly, in last place at the All-Star Break – when Farrell had the honor of managing the American League team to a win. It was a worst-to-first-to-worst odyssey during the regular season with Boston back in last place again. In 2015, the Sox remained mired in last place again. But in 2016, the Red Sox finished first once more. There was no middle ground; it was feast or famine. From 2012 through 2016, it was worst-first-worst-worst-first.

The 2016 Red Sox were, however, swept by the Cleveland Indians in the Division Series. The day after the final game of the ALDS, GM Dave Dombrowski announced that John Farrell would be back in 2017.

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Sources:

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Farrell’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Author interview with John Farrell, August 21, 2014. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from John Farrell are from this interview.

2 Boston Globe, July 17, 2014.

3 Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 16, 2002.

4 Los Angeles Times, April 8, 1988.

5 Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 7, 1988

6 Orange County Register (Anaheim, California), February 25, 1992.

7 Orange County Register, April 16, 1993

8 Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 16, 2002.

9 Albany Times-Union, October 22, 2006.

10 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 21, 2008.

11 Boston Globe, October 17, 2006.

12 “I hired a guy who went to Case Western Reserve University, a Japanese student, to get some familiarity. And then in spring training, the Red Sox had hired a language teacher. So Daisuke, Hideki Okajima, myself, and the instructor, we had three mornings a week for half an hour. The instructor would teach them English; they would teach me Japanese. It helped us kind of form a different type of relationship other than just on the field.”

13 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 21, 2008.

Full Name

John Edward Farrell

Born

August 4, 1962 at Monmouth Beach, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.