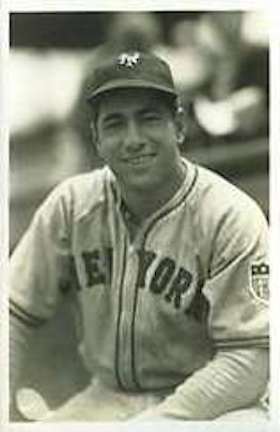

Babe Barna

Herbert “Babe” Barna was a star football player in college, an end who excelled as a receiver. He had “mercury in his shoes and glue on his finger tips.”1 He starred at football, basketball, and baseball at West Virginia University and received an offer by Bert Bell of the Philadelphia Eagles to play professional football after the 1937 baseball season had ended. But scout Ira Thomas of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics had gotten to him first. He’d signed to play baseball, and elected not to become a two-sport pro for fear of suffering an injury that could cost him his baseball career.2

Herbert “Babe” Barna was a star football player in college, an end who excelled as a receiver. He had “mercury in his shoes and glue on his finger tips.”1 He starred at football, basketball, and baseball at West Virginia University and received an offer by Bert Bell of the Philadelphia Eagles to play professional football after the 1937 baseball season had ended. But scout Ira Thomas of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics had gotten to him first. He’d signed to play baseball, and elected not to become a two-sport pro for fear of suffering an injury that could cost him his baseball career.2

It may have been a wise decision. This was still the Depression, and his father was a coal miner. Concern about a football injury was rooted in family experience; in 1922, when Babe was a young boy, his older brother Arthur was badly hurt in a high school football game. Gangrene set in. Arthur Barna suffered for some months, bedridden, and finally died.3

Babe Barna enjoyed a lengthy career as an outfielder in professional baseball that lasted from his college graduation in 1937 through the 1952 season, playing in over 2,000 games, though only 207 were at the major-league level. He played in five seasons from 1937 through 1943, mostly for the New York Giants, though he’d begun his big-league career with the Athletics and ended with the Boston Red Sox. During those five seasons, he was up and down from the minors and actually wore a total of seven different uniform numbers in his five years of major-league ball.

Barna was big for his time, standing 6-feet-2 and weighing in at 210 pounds. He was born in Clarksburg, West Virginia, on March 2, 1915, the son of Hungarian immigrants Tony and Rosie (Chalnak) Barna. Tony Barna had come to America in 1891, Rosie in 1896. They had four known children – Ethel, Arthur, James, and Herbert – at the time of the 1920 census, which found them living in Jenkins, Kentucky. Ten years later they were in Simpson, West Virginia; Arthur had died and Ethel was no longer living in the family home. James was 19 and working as a laborer in a tin mill. Herbert, who became known as Babe in college, was apparently an exceptional athlete and a good enough student that he graduated from Bridgeport (West Virginia) High School and received a B.S. in Physical Education at West Virginia University in Morgantown.

Immediately on graduation in June 1937, he was signed by the Athletics and had the opportunity to play in one game with the big-league team before being sent to the minors. He had experienced an injury that could have cost him the chance. The Athletics had talked with him in the summer of 1936 and expressed an interest in signing him. There was a condition, though; they asked him to forego college football during his senior year. After mulling it over, he came out late for the football team that fall, but decided he wanted to play, and he did – until he broke his ankle in a Thanksgiving Day game against George Washington University.4 That probably put an end to any flirting with becoming a two-sport pro. There were reportedly scouts from as many as five major-league teams following him, but he signed with the Athletics.5

Barna’s first major-league game was on June 16 at Shibe Park against the St. Louis Browns. He played first base – the only time in the majors or minors he played anything other than outfield, though he’d played first base in college – and had three at-bats, striking out once. His next four appearances were in September, as a pinch-hitter. His first base hit came on September 23 against the White Sox.

After his debut and before his return as a September call-up, he was assigned to play for the Albany Senators in the New York-Penn League. He appeared in 73 games, batting .283 with five homers and 40 RBIs. When back with the Athletics, he had his first big game on September 27 in Boston. Playing left field in both games of the day’s doubleheader, he was 0-for-3 with a walk and a strikeout in the first game, and 3-for-4 with a double and two runs scored in the second game. He’d taken early advantage of Boston’s Bobo Newsom, who had thrown a complete-game 6-2 five-hitter in the opening game, then decided to pitch the second game, too. Newsom didn’t make it through three. Barna’s first runs batted in came on September 29 in New York, two of them playing a big role in a 3-0 win over the Yankees. The next day, he was 3-for-7 against the Yankees again, with a two-run homer off Frank Makosky and another RBI as well, providing the margin in a 6-3 Philadelphia win. He hit another homer over the right-field fence (Barna batted left-handed, and threw right-handed) on October 2, another three-RBI day.

He’d hit .389 in his first 38 plate appearances (.421 on-base percentage), with nine RBIs. In mid- December 1937, he married Lillian Whaley.

Barna started and closed the season with Philadelphia in 1938, with two singles and five strikeouts in 14 April plate appearances and two singles (without a K) in 19 September plate appearances. He was thus .133 in major-league ball for 1938. Most of the season had been spent in the Class-A Eastern League, playing for Williamsport and hitting .302.

Barna trained with the Athletics for most of the spring of 1939, but on April 8 he was optioned to the Chattanooga Lookouts.6 In 145 games, he hit for a .317 average with 20 homers, and drove in 92 runs.

Memphis acquired his contract from the A’s for 1940.7 One story said that the Athletics recalled him from Chattanooga and “re-optioned” him to Memphis.8 Another more mysteriously reported that Memphis had “obtained [him] by the devious winter trade route from Chattanooga.”9 It was the same league, the Southern Association, just a different team. He played in 149 games, hit a very comparable .307 with 12 homers and 88 RBIs. His best game saw him hit a home run, a double, and two triples (he could have had a cycle if he’d stopped at first base on one of the triples), with four RBIs in the July 5 game against Birmingham.

Before the 1941 season, Barna was sold to the Minneapolis Millers (American Association). He got off to a strong start, on his way to a .336 season, with a league-leading 29 stolen bases, 24 homers (second in the league), and 105 runs batted in. On July 22, the New York Giants purchased his contract from Minneapolis. He was leading the AA in batting average at the time. Though manager Bill Terry wanted to bring him to New York immediately, he arrived after the AA season was over and played outfield in 10 games for the Giants, batting .214 with one homer (in his first game) and five RBIs. It wasn’t the first time he’d played at the Polo Grounds; he’d played there in 1934 for West Virginia in a football game against Fordham.

Barna was the Giants’ first-string left-fielder in 1942, appearing in 104 games and batting .257 with a .333 on-base percentage. Probably his best game of the year was on June 15 when he hit a double, a triple, and a home run, and made “the best fielding play with a leaping one-handed catch…near the scoreboard in left in the ninth.”10 Another highlight had come on June 13, in an exhibition game against the Great Lakes Naval Training Station team, when his two-run homer in the 10th won the game for the visiting New Yorkers. He drove in 58 runs, several times accounting for the difference in games the Giants won, such as his four RBIs in a 8-3 win on July 11 against the Cardinals. A pinch-hit sacrifice fly in the bottom of the 11th on August 1 won another game.

There were less spectacular contributions, such as singling in the 10th inning in Brooklyn on May 29. He moved to second base on a single, then to third when a batter was hit, and scored when the Dodgers failed to pull off a double play to close out the inning.

In 180 chances in the outfield, he made only three errors.

With Johnny Mize heading into military service in 1943, the Giants worked out Barna at first base during spring training, but he wasn’t all that keen on the idea and manager Mel Ott was not sufficiently impressed.11 He kept Barna in left field, where Barna played 40 games through June 12.

On the 14th, the day before the trading deadline, he was dealt to the Boston Red Sox straight up for left-handed pitcher Ken Chase. Chase had walked 11 batters in four innings in his last game for the Red Sox. Barna was batting .204 at the time, with12 RBIs. The Red Sox hoped the change of scene might make all the difference. He had a reputation of being “lazy…lacks the winning spark.” John Quinn of the Boston Braves said, “If Joe Cronin can light a fire under him, Babe ought to help the Red Sox.”12

Back in the American League, Barna kicked off a ninth-inning rally in his first game for Boston, hustling to make two bases, and scored the winning run. On June 20 he hit a two-run homer over the right-field wall in Philadelphia to boost the Sox to a 6-5 win. Overall, however, he failed to produce much for the Red Sox, batting .170 with 10 RBIs in 30 games. The Red Sox finished seventh, the Giants finished eighth. Barna hadn’t lasted past July, however. On July 30 he was released outright to the Louisville Colonels in exchange for outfielder Robert Emmett O’Neill.

Even in Double A, depleted of talent as were the majors, Barna seemed to struggle, batting .233 with 13 RBIs in 49 games. He’d passed a pre-induction physical for the Navy in early February 1944, but was never summoned to serve. He improved markedly, back in Minneapolis in 1944 and 1945, batting .298 and .309 respectively, with 24 homers and 25 homers and 181 RBIs over the two campaigns.

Barna stuck with Minneapolis for the first three postwar seasons as well, 1946 through 1948, with 28 homers and 112 RBIs in 1946 and two more solid years. He was back in the Giants’ system, but never got the call to come back to New York.

In 1949 he signed with the Nashville Vols and helped his team win the pennant. His 42 homers would have won the Southern Association title, had not teammate Carl Sawatski hit 45. Barna drove in 138 runs, but Sawatski drove in 153. Barna batted at a .341 pace, fourth in the league. The team’s Sulphur Dell ballpark had a short right-field fence which helped left-handed hitters to better numbers on offense. At one point in the 1949 season, he had hit 28 home runs at home and only eight on the road.13 As the Vols’ right fielder, he had to negotiate a steep slope up to the fence. He warned the club’s second baseman to stay out of the way whenever he chased a popup downhill, “in case my brakes give out.”14 Barna was called away just before the playoffs due to his wife’s illness, but was able to return and help Nashville prevail. The Vols won the Dixie Series as well, Barna scoring the winning run to beat Tulsa in the bottom of the 10th in the deciding game.

On December 8, Barna was traded to the International League’s Baltimore Orioles in a three-way trade. In 1950, playing Triple A, he hit .295 in 118 games with 62 RBIs. He was back with Nashville for the 1951 season, and hit a league-leading .358 with 19 homers and 94 runs batted in.

Barna had one final season in professional baseball, in 1952 for the Double-A American Association’s Toledo Mud Hens/Charleston Senators (the franchise shifted from Toledo to Charleston on June 23). The team finished in last place. His 72 RBIs were more than double the production of all but two of his teammates. Fred Taylor, with 45, ranked second.

In early 1953 the Charleston club sold his contract to Lincoln, Nebraska (Western League), but it was reported that he “may stay out of baseball this year and stay in the supper club business with Rollie Hemsley, ex-major loop catcher.”15 Hemsley had also been his manager in 1952. They started a company, the B & H Sportsman’s Club, and Babe Barna was the president and manager of the private social club in Charleston.

There were a few bumps in the road in the restaurant business, and the partnership. There had to be an interesting story behind the brief mention in a United Press story that said Hemsley learned “he was a much bigger success as a baseball player than as an entrepreneur,” adding, “Later, Hemsley started his own restaurant but before long he announced he was going to get out of it ‘if business doesn’t pick up any better than it has in the past year.’”16

A few years later, Barna was back in the news, given a 120-day suspended jail sentence for charges of illegal sale and possession of whiskey.17 It may have been a private social club, but whether the membership bar was set high enough may have been called into question again in 1958, when club member George Goff, Jr., 28, stabbed Barna in an “altercation” in the club, giving him a 14-inch pen-knife wound across his abdomen. “He had been cuffing me around and I got tired of it,” Goff told police.18 The police ordered the closing of the club, but it reopened after Barna got out of the hospital.

Babe Barna was still a relatively young man, at 57, when he suffered a stroke and died a week later in Charleston, on May 18, 1972. He is buried at Mountain View Memorial Park in Charleston, West Virginia.

He had been scheduled to be inducted into the West Virginia Sports Hall of Fame on May 21.

Barna was survived by his wife and two children.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Barna’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Gordon Cobbledick, “Rodak To Carry Defensive Load,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 13, 1936: 20.

2 Unidentified September 30, 1937 newspaper clipping from Barna’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Ibid.

4 Associated Press, “Loyalty May Cost Barna Job,” Washington Evening Star, November 28, 1936: 32.

5 Jack Cuddy, “In This Corner,” Charleston (South Carolina) News and Courier, April 13, 1937: 8.

6 Some sources report that his contract was purchased by the Washington Senators on April 9, but at least one report by the Associated Press noted him as “property of the Athletics.” Kenneth Gregory, “Vol Grid Star Able Talent Scout for Team,” Washington Evening Star, July 23, 1939: 44.

7 Associated Press, “Many New Faces, Including Four New Managers, Will Be Seen in Southern Loop Parks,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge), December 1, 1939: 33.

8 Wirt Gammon, “Cuyler Makes Many Changes in 1940 Lineup,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 5, 1940: 20. Gammon was the sports editor of the Chattanooga Times.

9 William J. Tucker (United Press), “Close Race Seen in Southern Loop,” Charleston (South Carolina) News and Courier April 8, 1940: 6.

10 John Drebinger, “Barna, Ott Wallops Homes in 6-2 Game,” New York Times, June 16, 1942: 28.

11 John Drebinger, “Ott Decides Barna Is Unable To Make the Grade As Possible Mize Replacement,” New York Times, March 18, 1943: 25.

12 Ed Rumill, “Babe Barna A Potential Star for Sox Outfield,” Christian Science Monitor, June 15, 1943: 14.

13 F. M. Williams, “They Ring the Bell Louder in the Dell,” Atlanta Constitution, July 17, 1949: 4D.

14 Interview with Buster Boguskie by Warren Corbett, 1993.

15 Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, March 8, 1953: 15.

16 United Press, “Hemsley, New A’s Hill Coach, Glad At Chance,” Trenton Evening Times, December 24, 1953: 20.

17 Associated Press, “Babe Barna Fined,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, April 6, 1957: 5.

18 Associated Press, “Ex-Soxer Club Brawl Victim,” Boston American, February 24, 1958: 17.

Full Name

Herbert Paul Barna

Born

March 2, 1915 at Clarksburg, WV (USA)

Died

May 18, 1972 at Charleston, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.