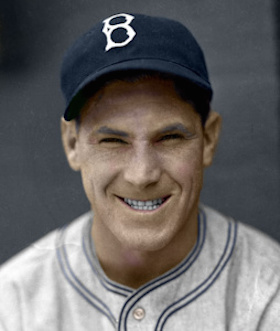

Buddy Hassett

Buddy Hassett was a New York boy who played for two of his hometown teams and almost made the trifecta. The first baseman had two distinctions: his ability to put the bat on the ball and his tenor voice. “The Bronx Thrush” would sing “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” at the drop of a leprechaun. He batted, threw, and sang left-handed.

Buddy Hassett was a New York boy who played for two of his hometown teams and almost made the trifecta. The first baseman had two distinctions: his ability to put the bat on the ball and his tenor voice. “The Bronx Thrush” would sing “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” at the drop of a leprechaun. He batted, threw, and sang left-handed.

Hassett struck out just once in every 33 plate appearances, never more than 19 times in a season. But he was a singles hitter playing a power position, and was passed around to three teams in seven years before World War II ended his big league career.

John Aloysius Hassett was born in the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City on September 5, 1911, the first of five children of John J. Hassett and the former Hannah Ford. John J., a plumber, became the Tammany political machine’s Democratic leader in the 8th assembly district in the Bronx. He was rewarded with an appointment to the Municipal Examining Board of Plumbers, the licensing agency for the trade.

Buddy said he and other Irish boys grew up fighting their Jewish and black neighbors. He also grew up with a baseball and bat in his hands. His father, a left-handed former semipro pitcher, was a Yankee fan, and the four Hassett brothers were regulars in the bleachers at Yankee Stadium. Buddy, Barney, Billy, and Tom all played college basketball. Billy, an All-American at Notre Dame, spent five years in the NBA and its predecessor leagues. They were not tall; Billy and Buddy were 5-foot-11 guards.

The oldest brother was outstanding in both sports and made his mark early as a singer. “I did a little singing in the Paulist church choir on 59th Street when I was growing up,” he said, “and then we moved to the Bronx. My father ran the Shamrock Democratic Club, and he’d have parties up there and I used to sing. I didn’t have any formal lessons.”1 He described himself as a crooner who patterned his style after his favorite, Bing Crosby.

Buddy was captain of the basketball and baseball teams at Manhattan College. He also played semipro baseball under the name Moore and sang during rain delays to keep the fans from going home. The day after he graduated in 1933, Yankee scout Paul Krichell signed him for a $1,600 bonus.

“There’ll be no athletic bums in our family,” Buddy’s father told him. “You’ve got three years. Make good, or you’ll go into plumbing, where you can be sure of making a living.”2 The boy had already tried plumbing, and hated it.

Three years was all he needed. Hassett hit over .330 in all three minor league seasons. In his second year he set a Piedmont League record with 56 stolen bases for Norfolk. Reaching the top level of the minors at Columbus in 1935, he missed half the season after he broke his right ankle crashing into a catcher while running out an inside-the-park home run.

By then he realized he had made a mistake signing with the Yankees. With Lou Gehrig showing no indication of vacating first base any time soon, Hassett asked to be traded. Bill Terry, the manager and first baseman for his mother’s favorite team, the Giants, wanted him as a backup, but couldn’t agree on a deal. Instead, Terry bought Sam Leslie from Brooklyn, and the cash-poor Dodgers used some of the Giants’ money to buy Hassett for a reported $20,000 and two players.3

The new Dodger introduced himself to New York baseball writers by singing at their annual dinner in January 1936. On a train headed south for spring training, he made fans of fellow passengers when he sang a crying baby to sleep. More important, his bat impressed manager Casey Stengel, who put the 24-year-old in the Opening Day lineup. Hassett’s first big league hit drove in the Dodgers’ first run of the season. He hit safely in 15 of the first 16 games and was soon batting third or fourth in the order.

As the Dodgers sank to seventh place, the rookie first baseman was one of the few bright spots. Playing every inning of every game, Hassett batted .310 with a .755 OPS, 82 RBIs, and 11 triples, all career highs. He struck out only 17 times in 683 plate appearances.

“I decided to try to meet the ball,” he explained, “and I guess I [choked up] on the bat a little bit so I had better control of the barrel of the bat. It’s a matter of eyes and muscle control, but I always tried to get a piece of the ball. If you notice, I didn’t get many bases on balls, either [no more than 36 in any season]. I believed that the idea was to hit the ball.”4 He sacrificed power for contact; he hit only 12 home runs in his seven-year career.

The muck of New York City politics splattered Hassett’s celebration of his rookie season. After Fiorello La Guardia was elected mayor on a reform ticket in 1933, the new administration had begun investigating the activities of the Tammany machine. The investigation caught up with John J. Hassett in the fall of 1936. He was convicted of accepting bribes to approve plumber’s licenses—the going rate was $450 to $500 for a passing grade on the licensing exam—and sentenced to two to four years in Sing Sing prison.

Hassett played every inning of every Dodger game until May 31, 1937, when a pitch from the Giants’ Carl Hubbell broke his left wrist. Hassett stayed in the game as the Dodgers ended Hubbell’s record 24-game winning streak, and gutted it out for seven innings in the second game of the Decoration Day doubleheader before he sat down.

He was batting .365 when he got hurt. Returning after three weeks, he watched his average dwindle to .304 by the end of the season. Still, Dodgers president Larry MacPhail awarded him a reported $1,500 raise, to $9,000, for 1938.

When Hassett signed the contract on March 4, MacPhail let him in on a secret that might explain the generous pay boost: He was about to lose his job. MacPhail, wanting more power at first base, was close to a deal to buy slugger Dolph Camilli from the Phillies. MacPhail told Hassett the Dodgers wanted him to learn to play the outfield or, if he wished, the club would try to trade him. Hassett chose to stay with Brooklyn. When the Dodgers announced the acquisition of Camilli two days later, Hassett told the writers he was glad to have the new power hitter and was confident he could handle left field.

Of course he didn’t want to leave home; Hassett lived with his parents and took the subway from the Bronx to Brooklyn. He also had his singing career to consider. In addition to singing the national anthem in uniform before some games, he had developed a vaudeville act with radio announcer Stan Lomax. They played the RKO and Brooklyn Strand theaters, filling the time between movies with songs and jokes. Broadway columnist Hy Gardner wrote, “Hassett plays 1st base for the Brooklyn Dodgers and hopes some day to get to 2d base in the theater league.”5 A lukewarm critic said the ballplayer “sings in a satisfying manner.”6

The 1938 season had Hassett singing the blues. Left field was not the Garden of Ease he had anticipated. He was charged with the second-most outfield errors in the league despite starting only 69 games in left. The Brooklyn Eagle’s Tommy Holmes commented, “He isn’t a finished outfielder yet, probably never will be.”7 The writer praised him for making the best of the situation with a smile on his face. Hassett’s hitting suffered until a second-half surge lifted him to his usual level: .293/.356/.361. He went 13-for-37 (.351) as a pinch-hitter.

Hassett also had differences with manager Burleigh Grimes. He thought Grimes resented his friendship with Stengel, Grimes’s predecessor. In September Grimes benched Hassett to try out young players. Hassett suspected a different motive: His contract called for a $500 bonus if he played in 115 games. One report said Camilli learned about it and faked an injury on the last day of the season so Hassett could make his 115th appearance, but MacPhail insisted he had planned to pay the bonus anyway.

While performing at the Strand during the offseason, Hassett said, “This four-a-day [shows] keeps me from thinking too much about where I’ll play next year.”8 The answer turned out to be Boston, where Stengel was managing the Bees, the artists formerly known as Braves. When he was traded, Hassett said, “I had my best year in baseball under Stengel and I’m tickled to be back with him.”9

Moving from one losing team to another, Hassett’s first challenge was to displace first baseman Elbie Fletcher, a local boy who was a slick fielder but not yet much of a hitter. Hassett opened the 1939 season in right field. By June Fletcher was batting .250 and Hassett 100 points higher. The Bees traded Fletcher to Pittsburgh. Back at his normal position, Hassett finished at .308/.342/.354.

The club tried out another first baseman, Les Scarsella, in 1940, but Hassett held onto his job at least temporarily. In June he tied a National League record by hitting safely in 10 consecutive at-bats (he drew two walks during the streak). Except for that outburst, he struggled through the worst year of his life for no apparent reason. It still bugged him 50 years later: “I’d have four hits [one day] and then nothing.” He was hitting in bad luck; his .242 batting average on balls in play was nearly 60 points below his career norm. He was benched in September and wound up at .234/.273/.293.

The Bees, stuck in seventh place, reclaimed their old nickname, Braves, and found a new first baseman for 1941: Babe Dahlgren, the man who had replaced Lou Gehrig in the Yankees lineup. Dahlgren had some power but was a low-average hitter. Hassett sat while Dahlgren hit five home runs in the first month, more than Hassett’s total for the previous four years. But Dahlgren was batting only .218 when Hassett got his job back. He hit .296/.354/.346 as the Braves slouched to their third straight seventh-place finish.

Hassett’s career came full circle after the 1941 season when Boston traded him to the Yankees as part of a deal for a top outfield prospect, Tommy Holmes. The Yankees had been searching for a first baseman since Gehrig’s forced retirement three years earlier, but they had no high hopes for the 30-year-old Hassett. At first he was said to be ticketed for their Newark farm club. Even after the 1941 first baseman, Johnny Sturm, was drafted into the army, manager Joe McCarthy said Hassett would be a backup.

McCarthy intended to hand the starting job to rookie Ed Levy, who the Yankees hoped would become a popular Jewish star in the New York market. Just one hitch: Levy wasn’t Jewish. He had taken his stepfather’s name and now preferred to use his birth name, Whitner. Club president Ed Barrow told him that if he wanted to be a Yankee, he would answer to Levy.

By any name, he was not the answer. Levy hit .122 in 13 games before he was dispatched back to the minors. Hassett got the job of his boyhood dreams, first baseman for the New York Yankees. “Having New York on your shirt is worth 20 points on your batting average,” he crowed.10

Not really. He gave the Yankees a decent year: .284/.325/.364, including a 20-game hitting streak. Always an opposite-field hitter, he learned to pull the ball toward Yankee Stadium’s short right field wall and recorded a career high in home runs—five, all in his home park. Joe DiMaggio called him “the best first baseman the Yankees have had since Lou Gehrig.”11 That was damning with faint praise. Hassett’s 27 extra-base hits would have been about two months’ worth for Gehrig.

Hassett stood in awe of DiMaggio, the best player he had ever seen. “He never looked like he was trying,” Hassett remembered. “He had those long strides, and he’d be there before you know it and make the plays.”12

After being stuck on losing teams throughout his career, Hassett rode the pinstriped coattails into the 1942 World Series. In Game One against the St. Louis Cardinals, he broke up a scoreless tie with a fourth-inning double that knocked in DiMaggio. In the eighth he singled to score DiMaggio again as the Yankees won, 7-4. He added another single the next day.

In Game Three the Yankees’ leadoff batter, Phil Rizzuto, beat out a bunt in the bottom of the first. As Hassett walked to the plate, he got the sacrifice sign. “Joe McCarthy never [sacrifice] bunted in the first inning in his life,” he said later. When he squared around, Ernie White’s pitch smashed his left thumb, ending his World Series and, as it turned out, his major league career.

Hassett expected the army to call him after the season, so he made two decisions. He married his girlfriend, Veronica Mackin, a former nightclub dancer who was called “Ronnie,” and he enlisted in the navy. He explained, “I figured if I had to go I wanted to be clean and neat and not in the mud.”13

With his college degree, Hassett qualified for an officer’s commission. He served as an instructor at the Naval Pre-Flight School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and coached and played for the baseball team, the Cloudbusters. Teammates included Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, Johnny Sain, and other major leaguers. On July 28, 1943, the Cloudbusters played a benefit game for war relief charities at Yankee Stadium against a team assembled from the Yankees and Indians and managed by Babe Ruth. The 48-year-old Ruth walked in a pinch-hit appearance. Hassett contributed two hits as the navy won, 11-5.

In August 1944 Hassett was assigned as athletic director aboard the new aircraft carrier USS Bennington, bound for the Pacific theater. The ship’s planes flew bombing raids against Japan and provided air support in the battles for Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Hassett left the navy in November 1945 as a lieutenant commander.

He came home to an uncertain future in baseball—or no future. At 34 he was the oldest of the four candidates for the Yankees’ first-base job. The 1941 regular, Sturm, returned along with the wartime incumbent, Nick Etten, and rookie Bud Souchock, the only right-handed batter. The Yankees made it clear that they had no place for Hassett; they offered him a job managing their Binghamton farm club, but he turned it down.

“I’m not going to say I didn’t get a fair shot,” he recalled years afterward. “I won’t say that.”14 He did get some playing time during spring training and made the Opening Day roster, which was expanded to 30 players to allow room for returning servicemen. But he never got into a regular-season game before the club released him on April 30. He agreed to join the Yanks’ Triple A team in Newark.

Now just a minute. Didn’t the GI Bill of Rights—the law of the land—say that all war veterans were entitled to get their civilian jobs back for one year, if they were able to do the work? It did, but major league owners, with their usual arrogance, declared themselves above the law. Commissioner Happy Chandler decreed that players were entitled to a 30-day trial, or 15 days during the regular season, no more.

Several players who were released or demoted to the minors filed lawsuits. Federal courts ruled that players must be paid their prewar salaries for a full year, whether their team kept them or not. US District Judge Lloyd Black of Seattle acidly remarked, “Since it has been argued correctly that baseball is the great American game that it is, certainly it ought to bear its share in meeting obligations to servicemen.”15

Hassett filed no grievance; it’s possible that the Yankees paid him his big league salary, probably $7,500. They may also have promised him a managing job, because that’s what he got in 1947. He managed for three years in the Yankees system, beginning at Class B Norfolk and advancing to Class A Binghamton and Triple A Newark. When the Yanks dropped him after the 1949 season, he hooked on with the Western League Colorado Springs White Sox for 1950.

At that point Bud and Ronnie decided he should stay home with his family, which now included daughters Patricia and Katherine. Settling in Hillsdale, New Jersey, he had worked in the offseasons for Eastern Freightways, one of the largest trucking lines on the East Coast. He became vice president of sales and stayed with the company for 40 years. He served as commissioner of the local Little League for several years and coached the US all-stars in the Hearst Sandlot Classic, an annual youth showcase in New York, from 1954 through 1963.

Hassett was still working at 85 because he needed the paycheck. His major league career had ended the year before the players pension plan began. He and other aging ex-ballplayers repeatedly petitioned the owners and the Players Association to be included in the plan, but both sides stiff-armed them. “That has soured me on baseball,” Hassett said.16

His brother Billy was among early NBA players who were retroactively given pensions. “Football and basketball have taken care of their old-timers,” Hassett told a writer. “Why won’t baseball?”17 A contemporary player, Pete Coscarart, had an explanation: “They’re just waiting for us to die.”18

Buddy Hassett died of bone cancer on August 23, 1997, shortly before his 86th birthday. Later that year Major League Baseball granted pre-1947 players a $10,000 annual payment for life, a fraction of what they would have received as members of the pension plan. About 75 of them were still alive.

Additional Sources

Associated Press. “Cancer Claims Hassett.” Marietta (Georgia) Journal, August 26, 1997: 16.

Baseball-reference.com.

Bedingfield, Gary. “Buddy Hassett.” Baseballinwartime.com, http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/hassett_buddy.htm, accessed September 30, 2016.

Boston Herald.

Boston Traveler.

Gladstone, Doug. “A Bitter Cup of Coffee: Postscript.” Albany Gov’t Law Review Fireplace Blog, May 2, 2011. https://aglr.wordpress.com/2011/05/02/a-bitter-cup-of-coffee-postscript/, accessed November 3, 2016.

Honig, Donald. Baseball Between the Lines in A Donald Honig Reader. New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1988.

“John ‘Buddy’ Hassett of Hillsdale, ex-Dodger.” Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), August 25, 1997. GenealogyBank.com http://genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/0F9F2A1E7B30027B-0F9F2A1E7B30027B : accessed 17 September 2016.

Mitchell, Joseph. My Ears Are Bent. Repr. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2010.

“Plumbing Official Guilty in Bribery.” Brooklyn Eagle, October 23, 1936: 13.

“USS Bennington.” Washington: Department of the Navy, Naval Historical Center, 2002. http://www.uss-bennington.org/hist-dpt-nvy-history.html, accessed October 10, 2016.

Notes

1 Richard Goldstein, “Buddy Hassett, 85, Ballplayer,” New York Times, August 26, 1997: D21.

2 Milton Gross, “Hassett, Typical New Yorker, Makes Good in Home Town,” New York Post, undated 1942 clipping in Hassett’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

3 Reports of the sale price range from $20,000 to $40,000. Contemporary accounts say the Giants paid the Dodgers $25,000 for Leslie on the same day the Dodgers paid the Yankees $20,000 for Hassett.

4 Buddy Hassett, December 1991 interview by Brent Kelley, in the SABR Oral History Committee collection.

5 Hy Gardner, “Night Club Newsreel,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 27, 1936: 12.

6 Herbert Cohn, “The Screen,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 3, 1938: 13.

7 Tommy Holmes, “Hassett One Dodger Who Clicked While Club Slumped,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 2, 1938: 14.

8 Holmes, “Hassett Finds Oasis From Idle Fancy in Stage,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 6, 1938: 14.

9 Bill McCullough, “Inability to Handle Hurlers Chief Reason for Todd Trade,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 19, 1938: 14

10 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, June 9, 1942: 29.

11 Ed Rumill, “In the Dugout,” Christian Science Monitor, August 21, 1942: 14.

12 Hassett interview.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Royal Brougham, “Judge Raps Contract, Orders Year’s Pay for GI,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1946: 2.

16 Hassett interview.

17 Peter Golenbock, “For Baseball Old-Timers, It Doesn’t Pay to Retire,” New York Times, July 27, 1997: S9.

18 Steve Love, “Grand (?) Old Game’s Golden Years,” Akron Beacon Journal, July 21, 2000: 14.

Full Name

John Aloysius Hassett

Born

September 5, 1911 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

August 23, 1997 at Westwood, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.