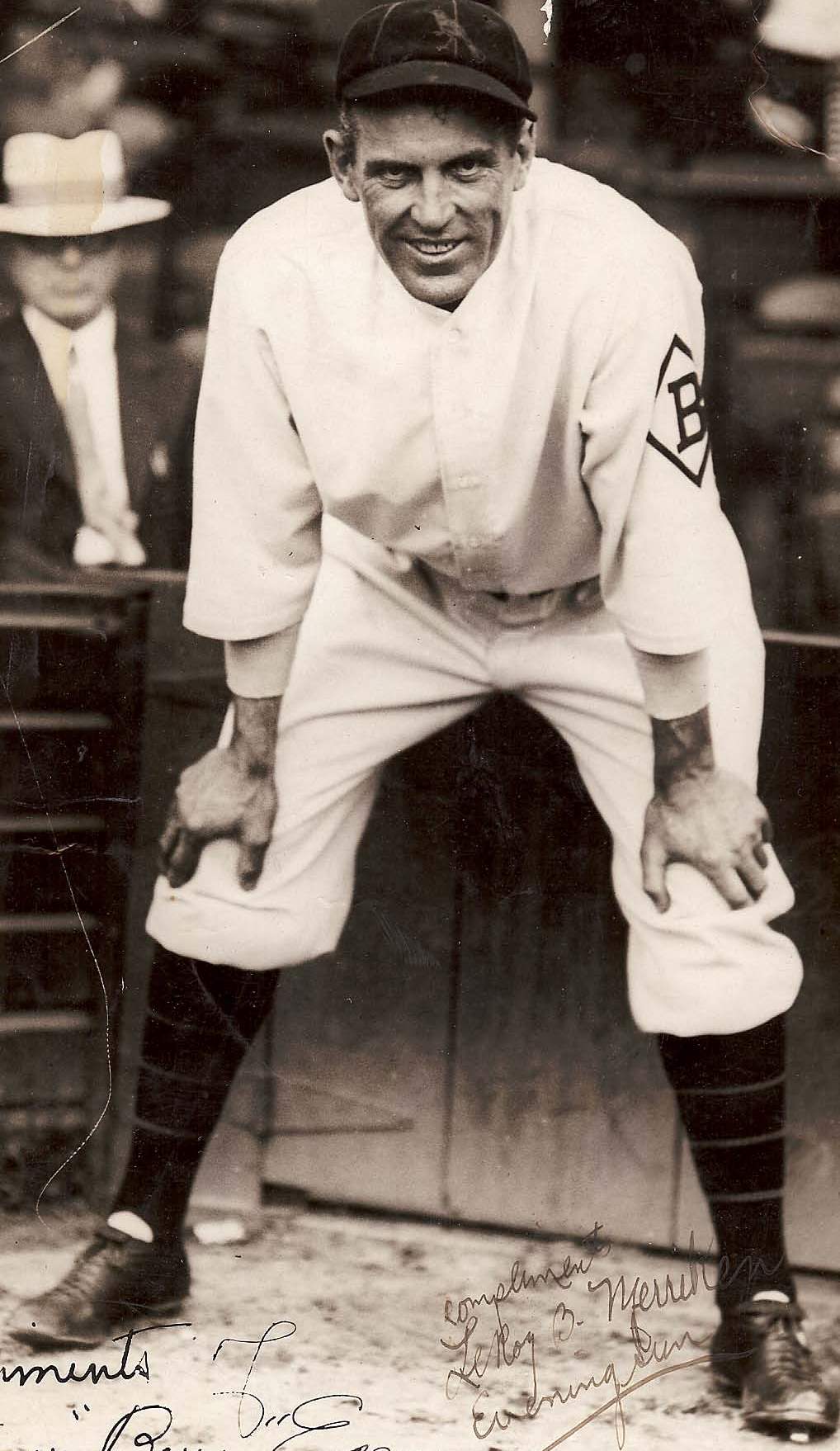

Ben Egan

“Yes, I knew him. He had huge hands with crooked fingers. He was a catcher, you know.”

“Yes, I knew him. He had huge hands with crooked fingers. He was a catcher, you know.”

“Hell Yes, Babe was here. When? I don’t know, maybe on Ben Egan day? No! I don’t recall ever seeing him. No! I don’t know of anyone who did.”

“Yes, I knew Ben. A great guy, everyone liked him. He was everybody’s friend. He often stopped by our house to talk with dad. I delivered his paper, later his mail.”

“He was a real practical joker. Wow! He worked on the second floor. He’d yell out the window at someone he knew walking on the sidewalk directly below. ‘Hey Joe,’ he might say. And Joe would look up and be met in the face by a bucket of water.”1

In Ben Egan’s hometown, Sherrill, New York, he and Babe Ruth are inexorably linked, to the extent that most current residents know more about Babe Ruth and his fabled 1910 pitching performance there than the marvelous amateur and professional baseball career of Ben, their playful native son.

While most baseball fans are familiar with Babe Ruth’s diamond exploits, Ben Egan’s career and reputation are little known and remain part mystery, part legend. Though Egan was predominantly a backup catcher during his four major-league seasons, he was an important cog for many of the best minor-league teams in baseball history. He was also an influential teammate and mentor during the early careers of three Hall of Fame pitchers, Lefty Grove, Stan Coveleski, and Babe Ruth. Egan spent about 22 years in professional baseball as a player, coach, and manager. When his professional coaching career ended in 1928 with the International League Baltimore Orioles at the age of 45, he continued managing and coaching for the next 15 years in his hometown.2

Quips and testimonials from Egan’s teammates during his playing days suggest he was a serious team leader while at the same time a locker-room comic and prankster. He was also by all accounts an exceptional pitching coach, a student of the game, and a good teammate. He captained the minor-league Orioles in each of the eight years he played for them. He finished his professional career as a coach with the Orioles in 1928 and then, though apparently on the fast track back to the major leagues as a coach or manager, he inexplicably retired from professional baseball, following the sudden, unexpected death of his friend and mentor Jack Dunn.

In his 1948 autobiography written with author Bob Considine, Babe Ruth stated: “Egan was my special friend. In those days old players paid little attention to rookies; in fact, they made it as tough as they could for them. . . . You would get a swift kick sooner than you’d get a word of encouragement. . . . But even if Egan played jokes and tricks on me, he took my part if other players went too far, and as he did most of my catching he gave me my first signs and a lot of good pointers.”3

Ben Egan’s parents, Patrick and Margaret, were born and raised in Ireland. The family spent its early years in Augusta, New York, in the state’s Mohawk Valley, where Ben was born. They moved their family to nearby Sherrill, in 1888. Ben was 5 at the time –the second youngest boy in a family of ten boys and two girls. His father, a farm laborer, died three years later.4

Despite the long winters and short summers in central upstate New York, Sherrill takes its baseball seriously. Oneida Limited f/n/a Oneida Community Limited, the silverware company founded by the 19th-century Oneida social and religious movement, supported and encouraged athletics, especially baseball. (Sherrill is adjacent to the city of Oneida.) OCL helped its employees sculpture and build Sherrill, a company town where many of its workers lived. Sherrill, a chic blue-collar community, has retained its small-town appeal and is still dotted with educators and professionals

Before turning professional, Ben Egan and his nine brothers played other town teams in central New York. When the Egan brothers’ team picture appeared in a local paper around 1902, offers began pouring in and “the Egans were invited to play everywhere”—everywhere apparently being county fairs and other local doin’s. In 1904 the oldest brother, James, was 37; Ben, the second youngest, was 20. Because many of the brothers had demanding jobs—three were New York City police officers, one was a local politician, and several, including Ben, worked at Oneida Community Limited—the team of brothers generally needed a few ringers to field a team and gradually disbanded.5

Egan signed for $50 a month with Rome, New York, in 1905 at the age of 21. Rome was a member of the independent Empire State League. Egan continued to play Empire State League baseball with Pen Yan and Auburn in 1906 and Seneca Falls in 1907. He also played briefly with Haverhill of the Class B New England League in 1906. In 1908, after pitching his case to Utica manager Charles Dooley, Egan caught for nearby Utica of the Class B New York State League. 6

Egan reached the major leagues briefly in 1908 as a late-season call-up to Connie Mack’s sixth-place Philadelphia Athletics. He caught in two games and had six at-bats and one hit. Mack thought Egan still young and relatively inexperienced and sent him back to Utica in 1909 for more seasoning.

In 1962 Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen interviewed Egan on his porch steps on Elmwood Place in Sherrill. Allen’s notes from the interview show that Egan didn’t recall his first major-league game (in Philadelphia on September 29, 1908). The Athletics played a doubleheader against the Cleveland Naps that day and Egan caught both games. Cleveland was in the midst of a historic pennant race with Ty Cobb’s Detroit Tigers. In the first game Egan was 0-for-2 off Heinie Berger. Berger walked Egan once intentionally as the Athletics lost, 5-4. In the second game, Egan doubled while going 1-for-4 off Bob “Dusty” Rhoads. The Naps had no stolen bases in either game, but Egan committed one error in the second game. The A’s lost the second game, 9-0.7

Egan went to spring training with the Athletics in 1910, but Connie Mack sold him to friend Jack Dunn, manager-owner of the Baltimore Orioles of the Eastern League (later the International League) with the understanding that when Egan matured he’d buy him back. Egan caught and captained the Orioles in 1910 and 1911. When Connie Mack saw Egan early in the 1911 season, he commented, according to the Baltimore Sun, that Egan was one of the best backstops he ever had seen. Mack purchased Egan for $7,000 in August 1911 with the understanding that he would complete the season in Baltimore and report to Philadelphia, the reigning world champion, the following spring.8

Ben Egan was a can’t-miss prospect, or so thought Baltimore Sun reporter C. Starr Matthews when he wrote in February 1911: “That Ben eventually will get the money and the glory, too, there is not the slightest doubt, unless he meets with some accident, for today he stands in a class by himself as a receiver in the Eastern League.”9

In 1912, though used sparingly, Egan threw out 56 base stealers in 46 games as catcher. Since he wasn’t a regular and often didn’t play the full game, his caught-stealing average of 1.17 per game was particularly impressive, ranking second in the American League.10 But in two trials with the Athletics, Egan didn’t hit. In his second stint with the team he hit only .174 in 138 at-bats. He could catch and throw, of that there was little doubt, but he couldn’t hit at that point in his career enough to stick in the majors. Still, he remained on the Athletics’ roster for the entire 1912 season. After the season, the Athletics released him to Baltimore, where in 1913 he played in 138 games and batted a respectable .280.

Egan had qualities that endeared him to legendary Baltimore owner-manager Jack Dunn. The Sherrill Sage, as he was often labeled in the Baltimore press, possessed good baseball instincts but, more importantly, the ability to nurture and instruct young players.

When Larry Ritter interviewed Hall of Famer Stan Coveleski for his 1960 classic The Glory of Their Times, Stan credited “Big Benny” with settling him down and getting him focused before his first major-league start in 1912: “All you do is throw it right to me,” Egan told him. “I’ll give you a good target. Just aim for my glove.” Coveleski threw a three-hitter.11

Egan and Ruth met in 1914, after Babe was signed by Jack Dunn. Ruth was 19, Egan 30. They were Orioles teammates just four months. On July 9, 1914, the Baltimore International League franchise, in first place but in a bit of a financial bind, started selling off its high-priced talent. Dunn sold Egan ($3,500), Ruth ($2,900), and Ernie Shore ($2,100) to the Boston Red Sox.12

Egan never got into a game for the Red Sox. On July 28 Boston traded him to Cleveland with pitchers Fritz Coumbe and Rankin Johnson for left-handed pitcher Vean Gregg. Gregg had won 72 games for Cleveland but would win only nine for Boston over the next three seasons. Egan spent 1914 and 1915 as a backup catcher with Cleveland. Once again, he didn’t hit enough to stick in the majors, batting .227 in 88 at-bats in 1914 and .108 in 120 at-bats in 1915. Cleveland released him to Newark of the International League before the 1916 season.

Egan suffered personal tragedies during this period as well: In April 1914 Ben’s oldest sister, Nellie Egan, 34, died of kidney disease. In July 1915 his younger brother Fred, 29, died from consumption, and in August an older brother John, 45, died after falling from a wagon.

Egan caught for Newark in 1916 and 1917; in the spring of 1918, Newark sold him to the Little Rock Travelers of the Class A Southern League, but before opening day the Orioles’ Jack Dunn snatched him back from the Travelers for $300. Dunn often referred to the deal as the “biggest, cheapest investment I ever made.”13

After winning 74 games and finishing third in the war-shortened 1918 International League season, Dunn’s Orioles won 100 games in 1919, 110 games in 1920, and 119 games in 1921 — three straight International League titles.

Egan’s most productive offensive season occurred in 1920 when he batted .331 and slammed eight home runs in 81 games for the Junior World Series champion Orioles. After the Orioles toppled the St. Paul Saints of the American Association, winning the final game on an inside-the-park home run by Joe Boley, Baltimore Sun sportswriter Vincent De P. Fitzpatrick said of Egan’s Junior World Series performance, “Good old Ben Egan was a tower of strength by reason of his experience in the two games in St. Paul. They call Bubbles Hargrave a great catcher in the American Association, but with all due respect to Bubbles, he looked wretched the way he tried to tag Boley at the plate. Ben would have had his man.”14

Egan was the primary catcher for the Orioles in 1921 at the age of 37. The 1921 team, considered by some baseball historians to be the best minor-league team ever assembled, fashioned a 27-game winning streak on its way to winning 119 games.

Though hampered by nagging minor injuries most of the season, Egan played in 95 games. He was the team captain and by all accounts, though baseball old at the age of 37, continued to be a very good defensive catcher with a strong throwing arm. He was also a consistent offensive contributor, hitting .270 and socking 18 doubles, one triple, and five home runs during the regular season.15 In the seventh game of the 1921 Junior World Series, Egan smacked two doubles and a homer in a 7-6 loss to Louisville in a Series eventually won by Louisville.

Orioles center fielder Merwin Jacobson, who hit .404 in 1919, said, when talking about former teammates Lefty Grove and Ben Egan: “The first ball (Jack Dunn) caught (from Grove) bounced off his glove. And about three or four times he couldn’t hold the ball it was so fast. They finally put Ben Egan in to catch him. He made Lefty a good pitcher.”16

Egan spent the early parts of his 1922 Baltimore spring training with the Orioles in Winston Salem, North Carolina. He had petitioned Dunn for his walking papers earlier in the spring so he could pursue a managerial career; Dunn refused because he thought he still needed Ben. However, during spring training Baltimore’s catching depth improved, and Dunn agreed to release his friend and confidant from his contract, and Egan moved to an International League rival, the Jersey City Skeeters, where he was named manager, vice president and a director. The Skeeters defied expectations under Egan, finishing fourth and winning more than they lost in the eight-team International League.

Shortly after it became public that Egan was leaving Baltimore, the Baltimore Sun commented, “No man on the club did more to help the Birds to nail down three successive flags. His good humor was proverbial, and he was the ‘life of the party’ all the time. A proficient and knowing catcher, he was more than a mechanical player, and he did wonders in bringing up such pitchers as Lefty Grove and others to their present skill. . . . Perhaps the most disconsolate man on the squad was Lefty. He made no effort to conceal the fact that he was losing his best friend, and when his roommate left, he was a lonely southpaw.”17

In 1921 Orioles teammate Harry Frank, who won 49 games his first two years with the club, complimented Ben Egan as a positive and patient pitching coach: “I think Ben Egan is one of the best catchers that ever stepped behind the plate. He has more pep than any man in the game, and uses it on the coaching lines if he is not playing himself. As for breaking in young catchers, he is a wonder and in a class by himself. He always has a word of encouragement for everyone, and that is one of the best things to help a new pitcher. He may raise Cain sometimes, but it is only for the best and designed to benefit the man at whom it’s aimed. I owe Ben Egan everything for without him I would have had an awful time during my two years with the champion Orioles.”18

Baltimore fans turned out on May 22, 1922, to honor their former catcher as they celebrated Ben Egan Day in Baltimore and toasted him as “perhaps the best-liked player that ever wore Oriole livery.”19 But later in the season the Baltimore Sun reported that a squabble had erupted between Egan and Dunn, and by season’s end the two old friends were no longer speaking. Or more to the point, Dunn was not speaking to Egan. Egan had been quoted as saying Dunn won many of his games because the umpires were showing favoritism. While this was an attack more on the umpires than Dunn, the Orioles’ owner-manager took it to heart and cut off his old friend. Since Dunn and the Jersey City owner, Joe Moran, were close friends, Moran immediately relieved Egan of his front-office duties. While this move hurt Egan, it also hurt the club, which sank to last place in 1923, losing 105 games with Egan as field manager but with little input on player movement.20

An undated excerpt from an unidentified newspaper obtained from an Egan family member, probably written during the fall of 1923, said of Egan’s reign as the Skeeters’ manager: “Egan expects an offer to return to Baltimore next season. This, it is declared, would be to the liking of Jack Dunn and Baltimore’s fans. At the last game in Baltimore between the Orioles and Jersey City, Egan received the greatest ovation ever accorded a player on that field. Fans were insistent that he get behind the bat, which he did and when he took his place at the rubber (home plate), it was fully two minutes that the fans howled their welcome and respect. It was a well-known fact that Moran, owner of Jersey City, gave Ben about the poorest support that any manager in the International wheel had. He not only refused to secure new players, but attempted to sell those he already had. That Egan made as good showing as he did with the material was considered remarkable.”

Egan’s next stop, albeit a short one, was as a coach with the Washington Senators. During spring training manager Stanley Harris brought him in to work with pitchers and catchers and coach the bases. But on June 1 Harris fired Egan and his other coach, Jack Chesbro, in favor of the comedy team of Al Schacht and Nick Altrock. The Washington Post headline read: “Baseball Comedy Pair is Re-united”; however, it might well have said “Egan, Chesbro Replaced by Two Clowns.” 21 (24 years later, in 1948, Schacht performed his comedy routine at Ben Egan Day in Sherrill.)

Egan’s next stop, albeit a short one, was as a coach with the Washington Senators. During spring training manager Stanley Harris brought him in to work with pitchers and catchers and coach the bases. But on June 1 Harris fired Egan and his other coach, Jack Chesbro, in favor of the comedy team of Al Schacht and Nick Altrock. The Washington Post headline read: “Baseball Comedy Pair is Re-united”; however, it might well have said “Egan, Chesbro Replaced by Two Clowns.” 21 (24 years later, in 1948, Schacht performed his comedy routine at Ben Egan Day in Sherrill.)

After being fired by Washington, Egan returned home. The Utica Utes of the New York-Pennsylvania League, struggling at the box office and on the field, quickly hired him to replace manager Ambrose McConnell; however, both his time and the Utes’ time in Utica were short-lived as on August 7, 1924, the team relocated to Oneonta, New York, where the Utes became the Indians, and Roy Thomas became the new manager.

Washington won the World Series in 1924. Egan was given credit in some circles for turning the pitching staff around in the spring before his dismissal. His success in Washington along with his previous accomplishments enhanced his reputation as a pitching coach and helped land him his next coaching job, with Brooklyn.22

Egan often said he had little to do with the success of Ruth, Grove and others he helped along the way; however, his pupils reported otherwise and the improved performance some of his hurlers enjoyed in the major or minor leagues speaks volumes about his ability to coach and nurture young pitching talent.

If coaching Brooklyn wasn’t enough in 1925, Egan also signed on to coach the Cornell University batterymen during the 1925 winter offseason. From early January until the end of February, he imparted his pitching wisdom by appointment only to the Cornell twirlers and backstops.23

After the 1925 season, former Philadelphia Athletics star Eddie Collins, about to start his second year as Chicago White Sox manager, hired his former teammate as his coach and assistant.24 In spite of the team’s marked improvement under Collins and his coaching staff (the team won 79 games in 1925 and 81 games in 1926) owner Charles Comiskey fired Collins at season’s end and replaced him with Collins’s old Black Sox teammate and catcher, Ray Schalk. The White Sox didn’t win more than 81 games again until 1937, and by then Schalk was history and Jimmy Dykes, the manager.

In 1927, after obtaining the recommendations from “Eddie Collins, Joe Judge, and a score of big-league players,” Georgetown University athletic director, Lou Little hired Egan to coach the Georgetown nine, replacing veteran coach John D. O’Reilly after O’Reilly’s 13 successful years there. In O’Reilly’s last year Georgetown won 12 and lost 9; in Egan’s first year the team won 13 and lost 8.25 The 1927 Georgetown University annual wrote of Egan: “Although he has been at the Hilltop but a few months, Ben Egan has already established himself as a favorite, not only with the baseball squad, but with all those fortunate enough to make his acquaintance. Beneath his modest and retiring manner, Egan conceals a vast knowledge of baseball, a force of character and a determination to win, which promises high success for the future Blue and Gray nines.”26

But Egan’s first year at Georgetown was also his last. Once again his old mentor, Jack Dunn, came calling. Initially, Egan thought he do both, coach the college team until June and join the Orioles thereafter; however, Dunn needed Egan’s instincts and insights from spring to fall.

Unfortunately for Egan and the Orioles, Dunn died shortly after the 1928 season ended. With his death the Oriole International League dynasty ended. Dunn’s widow appointed Dunn’s lawyer, Charles H. Knapp, as team president and spokesman. Knapp named Fritz Maisel field manager. Maisel, like Egan, was a former Baltimore player, coach, and captain.

Knapp also appointed George M. Weiss, then 33, as the Orioles’ first general manager. Maisel, by all accounts a good baseball man, kept the Orioles respectable, but the Dunn-Egan-Maisel success with pitchers couldn’t be duplicated as rookie management team of Knapp, Weiss, and Maisel produced only one 20-game winner during the ensuing four years.27 Egan does not appear to have stayed on with the Orioles in any official capacity or to have been considered as the new manager. According to press reports, Ty Cobb was the only other candidate considered. Egan, 45, returned to his upstate New York home permanently to start his new life.

Egan had married Leta Montross on June 30, 1910. They purchased their 69-acre farm in Sherrill on shady Elmwood Place in 1914 and maintained their home there for 54 years. One print source indicated that Ben and Leta had a daughter born in late 1911 or in the early days of January 1912; however, the town clerk of Vernon, where such vital statistics would be recorded, has no record of the birth and the local cemetery has no record of her death. Also, the surviving nieces and nephews and other local residents have no recollection of any Ben Egan offspring.

Baseball and Ben Egan were never far apart. After his exit from professional baseball he took a job at Oneida Community Limited. He apparently worked at various jobs through the years. In addition to his regular duties, OCL hired him around 1930 to manage and coach the company-funded semipro baseball team — an official position for Egan and his players complete with time cards and paychecks. Egan coached and/or managed the team into the early 1940s.28

Egan helped put Sherrill on the baseball map. While still an active player, he used his influence to arrange exhibition games between Baltimore and the OCL-sponsored semipro teams. Baltimore papers often mentioned his hometown in articles about him or the team. Writers frequently referred to him as the Sherrill Sage. Before radio and television, Egan’s Orioles brought to Sherrill quality players — former major leaguers, future major leaguers, and veteran minor leaguers of the day. One of those games, on May 19, 1914, took place while Babe Ruth and Egan were teammates on the Orioles. Ruth’s doesn’t appear in the box score; probably because he started and pitched the next day, May 20, in Rochester, New York.29

On May 16, 1948, the Sherrill and Oneida area community celebrated Ben Egan day in Sherrill. Among the baseball dignitaries in attendance were Egan’s close friend and former teammate, Chief Bender; New York Giants pitcher George “Hooks” Wiltse; former Philadelphia Athletics teammate Jimmy Walsh, an International League Hall of Famer; and the Clown Prince of Baseball, Al Schacht, who had crossed paths with Egan when the two coached in the nation’s capital.30

Ben’s name wasn’t actually Ben, it was Arthur Augustus Egan. Egan told Lee Allen he was called Ben because as a small boy he hung out with another boy, Ben Stewart. Arthur apparently wasn’t known very well by the town folk, so family members asked for Ben in hopes of finding tag-along Arthur at his side.31

Egan died on February 18, 1968, at the Utica State Hospital after a lengthy illness; he was 84. He is buried in the St. Helena’s Cemetery in Oneida, on the outskirts of Sherrill. He left no will. The court awarded his estate, cash and property valued at less than $15,000, to his wife, Leta Egan. She died on November 19, 1970, at the Oneida Nursing Home; she was 93.

The photo is a classic treasure, well known within Sherrill city limits but familiar to few outside the community. Ben Egan and Babe Ruth, old friends: Egan smiling in his Orioles uniform; Ruth, holding his bat, looking uncomfortable in Yankee pinstripes. Both men sit, backs against the lower grandstand fence, fans visible behind them. The date and place are lost in time, but it is probably the spring of 1920 or 1921 — at a reunion of sorts in Babe’s hometown. Babe, a young star, waits to take batting practice. Egan, a yannigan, a career bush leaguer, the old team’s captain, hangs there to chat and watch his old batterymate take his licks.

Best known for catching Babe Ruth’s first professional game, a 6-0, six-hit shutout of Buffalo on April 22, 1914, Ben Egan was a backup major-league catcher, journeyman minor leaguer, captain, coach, manager, prankster, and because of his work ethic, hustle and playful enthusiasm, a fan favorite–a blue collar guy with a heart of gold from the Silver City. He may not have made direct impact on the big stage, but as Joe Stadtmiller of Sherrill, an old coach himself, wrote in a novel published in 2009, individual success isn’t all that important a legacy, “what matters most is the process itself, the impact we have on those we touch along the way.”32

Sources

Allen, Lee. “Babe Ruth’s First Catcher.” Cooperstown Corner: Columns From the Sporting News 1962-1969. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1969.

Bready, James H. Baseball in Baltimore. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Creamer, Robert W. Babe: The Legend Comes To Life. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2005.

Flynn, Tom. Baseball in Baltimore. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Huhn, Rick. Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company Publishers, 2008.

James, Bill. “The Baltimore Orioles.” In The Bill James Baseball Historical Abstract. New York: Villard Books, 1986.

Jenkinson, Bill. The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs. New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2007.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball: Third Edition. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007.

Kaplan, Jim. Lefty Grove: American Original. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2000.

Keenan, Jimmy. The Lystons. Gaithersburg, Maryland: self-published, 2006.

Montville, Leigh. The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth. New York: Broadway Books, 2006.

Pendleton, Thomas A. “The 1919 Orioles.” In The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History N-21. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001.

Ritter, Lawrence S. Glory of Their Times. New York: Quill William Morrow, 1966.

Robertson, Constance. Golden Anniversary 1916-1966 Sherrill, New York, 1966.

Robertson, John G. The Babe Chases 60. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company Publishers, 1999.

Ruth, Babe (as told to Bob Considine). The Babe Ruth Story. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1948.

Stadtmiller, Joseph. American Bases. Sherrill, New York: self-published, 2009.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan and Company and Information Concepts Incorporated, 1969.

Weldon, Martin. Babe Ruth. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1948.

Wagenheim, Kal. Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974.

Ye Doomesday Booke. (Georgetown University Yearbooks select pages supplied by Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.: 1927 and 1928.

2009 Georgetown Baseball Annual (online).

Egan, Arthur Augustus. Oneida County, New York, Probate Court file, 1968.

Egan, Leta. Last Will and Testament, 1967.

Egan, Leta. Madison County, New York, Probate Court file, 1971.

Oneida County, Land Records.

The Quadrangle (published by OCL).

City of Sherrill Newsletter.

Baltimore Evening Sun

Baltimore Sun

Cornell Daily Sun

New York Times

Oneida Daily Dispatch

Philadelphia Sporting Life

Syracuse Post Standard

St. Louis Sporting News

Utica Daily Press

Washington Post

www.Baseball-Almanac.com

Acknowledgments

I would also like to thank the following for their cooperation or assistance:

Anita Ayers, San Francisco, California.

Tom Barthel (SABR), Clinton, New York.

Gene Carney (SABR), Utica, New York.

Robert Comis, Sherrill, New York.

Lyn Conway, Georgetown University.

Craig Crowell, Sherrill, New York.

Tom Elliot, Blue Bell, Pennsylvania.

Dwight Evans, Sherrill, New York.

Al Glover, Sherrill, New York.

Pete Glover, Sherrill, New York.

Art Hedderich, Sherrill, New York.

Peter Henrici (SABR), Cooperstown, New York.

Michael Holmes, Sherrill, New York.

Anita Ingalls, Oneida, New York.

Paul Jones, Oneida, New York.

Jimmy Keenan (SABR) , Glen Rock, Pennsylvania.

Jim McBride, San Jose, California.

Carl Sofranko, Opelousas, Louisiana.

Joseph Stadtmiller, Sherrill, New York.

Jack Stone, Sherrill, New York.

Bette Egan Vogt, Sherrill, New York.

Anthony Wonderley, Oneida, New York.

Kevin Zeise, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Augusta Town Clerk, Oriskany Falls, New York.

Baseball Hall of Fame, Research Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Madison County Surrogate Court, Wampsville, New York.

Mansion House Library, Oneida, New York.

Oneida City Clerk, Oneida, New York.

Oneida County Surrogate Court, Utica, New York.

Oneida County Clerk’s Office, Utica, New York.

Oneida Public Library, Oneida, New York.

Onondaga County Public Library, Syracuse, New York.

Rome Historical Society, Rome, New York.

Saint Patrick’s Cemetery Association, Oneida, New York.

Sherrill-Kenwood Cemetery Association, Oneida, New York.

Sherrill-Kenwood Public Library, Sherrill, New York.

Syracuse Public Library, Syracuse, New York.

Vernon Town Clerk, Vernon, New York.

Utica Public Library, Utica, New York.

Notes

1 Interviews with octogenarian Paul Jones, former mail carrier, paper boy, and postal clerk, whose father palled around with Ben Egan; nonagenarian Art Hedderich, retired Oneida Limited employee and Sherrill resident; Jack Stone, Sherrill resident and former Community Associated Clubs semipro player; brothers Glover, Al and Pete, now and forever Sherrill residents; and other locals. These quotes developed and edited from their remembrances. In his book The Gas House Gang, author John Heidenry wrote of 1934 ballplayers, having further perfected their accuracy, using and dropping water-filled balloons from upper-story hotel rooms on unsuspecting teammates, managers, reporters, and others.

2 In 1962 Egan told Lee Allen that he coached professionally until the beginning of World War II. Some Sherrill residents recalled him coaching until 1945, but, though the written records are spotty, other names show up as coaches or managers during the war years. It may be that Ben helped out and had no official title. He turned 65 in 1948.

3 Ruth, p. 28.

4 Egan’s parents lived in Augusta, New York, when he was born on November 18, 1883. Oneida County Clerk filings show that in 1888 Egan’s mother purchased the Cedar Street property in Sherrill. Ben and the younger siblings spent the rest of their childhood in Sherrill. He attended local schools through eighth grade; then he went to work at Oneida Community Limited for a dollar a day and played ball with his brothers until signing on with Rome in 1905 for $50 a month.

5 Baltimore Sun, February 12, 1911.

6 Records for this period are a little sketchy, but I believe this is accurate — some information from the Oneida Daily Dispatch, May 14, 1948, from Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition, and from Lee Allen’s Sporting News column in 1962 (referenced later). The Eastern League changed its name to International League and its classification to Double-A in 1912. There were three Double A (AA) classifications, then considered one level below the major leagues: the Pacific Coast League, the American Association, and the International League.

7 Washington Post, September 30, 1908. Egan received his first major-league intentional walk before he got his first hit.

8 Baltimore Sun, August, 9, 1911.

9 Baltimore Sun, February 12, 1911.

10 Baltimore Sun, January 26, 1913.

11 Ritter, p. 121.

12 Payments vary from $8,500 to $25,000; however, Ruth and others cited amounts and distributions that totaled $8,500. The payments may have been low because of the newly formed Federal League. Players were jumping leagues and owners didn’t want to invest too much because they feared players might jump to the Federal League. Boston Red Sox President Joseph Lannin indicated the price for the three players was $25,000 (New York Times, July 10, 1914).

13 News article (undated) from the Sherrill City historical archives, presumably from the Baltimore Sun or Syracuse Post Standard.

14 Baltimore Sun, October 18, 1920.

15 Keenan, p. 176.

16 Kaplan, p. 60.

17 Baltimore Sun, April 4, 1922.

18 Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1921.

19 Baltimore Sun, May 23, 1922. Baltimore honored Egan in his first game back in Baltimore as the new Jersey City manager.

20 Baltimore Sun, December 15, 1922.

21 The Washington Post, June 2, 1924.

22 Article from unknown New York paper (ca. March 1925), from Egan’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

23 Cornell Daily Sun, January 7, 1925.

24 Huhn, p. 223.

25 Washington Post, February 25, 1927.

26 1927 Ye Domesday Book, p. 385.

27 Bready, p. 186.

28 Oneida Daily Dispatch, April 9, 1931. There is an article and picture which suggest that Ben Egan was the previous season’s manager as well. The CAC baseball team, funded in part by Oneida Community Limited, paid the coaches and players as employees. According to Jack Stone, a former CAC player, and others, players and coaches would punch out of their regular jobs and punch in for their baseball jobs. Whether this was true during the early years is unknown; however, the news article announcing Egan’s appointment as the baseball coach had all the formalities of an article announcing a job promotion at OCL.

29 The Ruth-in-Sherrill story tracks back to one OCL official’s unpublished manuscript (ca. 1935); the story appears in Sherrill’s Golden Anniversary book (1966); it has appeared in local newspapers; it has appeared in the local City of Sherrill Newsletter; and a poster commemorating the game still hangs in the CAC clubhouse in Sherrill which states, among other things, that Ruth pitched at Kenwood Park as a member of the Eastern League Baltimore Orioles on September 1, 1910. The source for all these publications appears to have been the 1935 manuscript (or each other). The 1910 date is just plain wrong and suggests that the author had no written record readily available. The mistake appears to have emanated from a logical assimilation of faulty memories and half-truths sprinkled with a dose of wishful thinking. Ruth was 15 in September 1910 and still playing approximately 200 games a year for St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys.

30 Oneida Daily Dispatch, May 14, 1948.

31 Lee Allen, p. 11.

32 Stadtmiller, back cover.

Full Name

Arthur Augustus Egan

Born

November 20, 1883 at Augusta, NY (USA)

Died

February 18, 1968 at Utica, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.