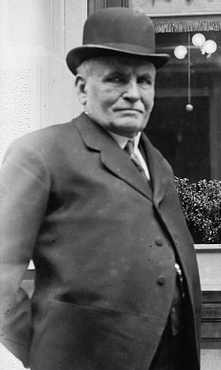

Ben Shibe

Called “the Edison of the sport,” by James C. Isaminger in a 1922 obituary, “Uncle Ben” Shibe was a major contributor to the development of the national pastime. It was his business savvy that helped turn a nascent game at his birth into a multi-million dollar enterprise by his death. As co-owner of the Philadelphia Athletics, Shibe would be at the forefront of baseball’s greatest innovations, from baseballs to stadiums. As William A. Phelon observed in Baseball Magazine, “[Shibe] is wise, shrewd, a clever calculator, a great money-maker….but it’s not so many years ago that he put his money and his shoulders back of what seemed a losing venture, showed himself a grim fighter and a dead game sport — and pushed the White Elephants to the front.”

Called “the Edison of the sport,” by James C. Isaminger in a 1922 obituary, “Uncle Ben” Shibe was a major contributor to the development of the national pastime. It was his business savvy that helped turn a nascent game at his birth into a multi-million dollar enterprise by his death. As co-owner of the Philadelphia Athletics, Shibe would be at the forefront of baseball’s greatest innovations, from baseballs to stadiums. As William A. Phelon observed in Baseball Magazine, “[Shibe] is wise, shrewd, a clever calculator, a great money-maker….but it’s not so many years ago that he put his money and his shoulders back of what seemed a losing venture, showed himself a grim fighter and a dead game sport — and pushed the White Elephants to the front.”

Benjamin Franklin Shibe was born on January 23, 1838, on Girard Avenue in Philadelphia. Poorly educated and handicapped by a childhood accident that required him to wear a steel brace on his leg, Shibe took a job as a conductor on a Philadelphia horse car. Soon after, he worked in a leather novelty establishment with a family member. There he made things such as whips and leather watch fobs. When the Confederacy’s Army of North Virginia briefly entered Pennsylvania in July 1863, Shibe answered the call for emergency volunteers to protect the city, joining the Pennsylvania 51st Infantry Regiment. After the crisis passed, the 51st Regiment was mustered out in September, 1863. It is unlikely that Shibe saw any combat during his brief career as a soldier. By 1870 Shibe was working as a conductor on the Philadelphia City Railroad.

With baseball’s popularity on the rise following the end of the Civil War, Shibe joined his brother John and nephew Dan, who had worked for a company that made cricket balls, in founding John D. Shibe & Co., which made baseballs for children and professionals. The company churned out many different brands of balls, such as the skyrocket, Bounding Rock, Red Dead Balls, Red Stocking and the Cock-of-the Walk. Their company supplied others, such as Alfred J. Reach, from the company of Reach & Johnson. Reach and Shibe were friends, and by 1882 Benjamin Shibe and A.J. Reach formed a new company, Reach & Shibe. However, John Shibe believed the name related to Ben’s former affiliation, so the name was changed to A.J. Reach and Company. They soon left the retailing part behind and concentrated on manufacturing. Occupying a huge factory, they had over 1,000 employees and controlled their industry. By 1883, the Reach factory was making 1.3 million baseballs and 100,000 bats per year.

Ben Shibe was not only concerned with manufacturing. He directed the Shibe Semi-Professional Team, which produced many professional players. During the 1880s, he became principal stockholder in the Athletic Club of the American Association. Although it was bankrupt by 1890, it signifies Shibe’s early passion for the game which his physical disability had prevented him from playing. Baseball Magazine writer F.C. Lane wrote in 1912, “Mr. Shibe was actuated solely by loyalty for baseball as the greatest of sports and not through any mercenary motives.” The truth is that he made many investments in teams that would never produce a penny of profit, although the publicity generated by those teams certainly didn’t hurt his sporting goods business.

The company that Shibe helped to build was critical to baseball’s development in the late nineteenth century. Throughout the mid 1800s, there was a problem with the stitching on the cover of baseballs. Usually, the tips of one “S” were fitted on either side of the waist of the other, so the stitches always “drew.” Since the cover was not smooth, the hide never had full protection. Shibe tried to fix that problem for many years, trying many different methods, always coming up short of the perfect design. Eventually he discovered that the nature of the spherical ball required the stitches to be grouped closer together at the end of the “S” — to be even with those at the waist — in a decreasing space of separation. In 116 stitches, it worked perfectly. In 1889 Shibe’s nephew, Daniel M. Shibe, was awarded U.S. patent #415,884 for the design.

In 1901 the American League gave its Philadelphia franchise to Connie Mack. In order to compete with the established National League Philadelphia franchise, Mack needed a local backer who would give the newcomers instant credibility and prestige. He also needed capital. Ben Shibe was just the right man. Reach was a minority stockholder in the Phillies, and Mack made it clear he intended to raid the Phillies for players, so Shibe hesitated to invest in the team. But he also believed a second major league was good for baseball. Reach felt the same way, and at his suggestion, Shibe agreed to buy no more and no less than 50 percent of the club. Mack had allocated 25 percent to two sportswriters, whose voting power he held, giving Mack and Shibe equal power. That way, neither man could do anything the other didn’t agree to. In reality, they never disagreed, and Shibe left the running of the team and all the baseball decisions to Mack. When Mack wanted to buy out the two sportwriters’ shares in 1912, Ben Shibe loaned him the money instead of letting his sons buy them and put 75 percent of the stock in Shibe hands. Trusting in Mack’s able leadership, Shibe’s franchise captured six American League pennants and three World Championships during his 21 years as team president.

Ben Shibe is probably best known for building the first steel and concrete stadium, known as Shibe Park. After growing weary of Columbia Park, which could scarcely hold 10,000 fans, Shibe constructed his new grounds in what was then the northern outskirts of Philadelphia, about four miles north of Independence Hall at the corner of Lehigh and 21st Streets. Designed in the French Renaissance style, the exterior featured terra cotta brickwork, a dark green slate roof, and a grand rotunda at the main entrance. Universally hailed at its opening as the greatest ballpark ever built, the 23,000-seat baseball palace cost $500,000 according to some reports, $300,000 according to others. The stadium opened on Monday, April 12, 1909, with both league presidents attending and invitations sent to all owners. The National Commission thanked Ben Shibe for, as the Washington Post reported, being, “the first person to take advantage of the situation and realize that the fan’s wishes had to be gratified; and that was accommodation.” In the nearly 100 years since Shibe Park opened, every new major league stadium has been built using steel and concrete.

That same year, Shibe made arguably his biggest contribution to the game with his company’s invention of the cork-centered baseball. The livelier baseball — which was introduced in the 1910 World Series and used in all games beginning in 1911 — led to an offensive explosion, extending base hits from singles to doubles, and doubles to triples. The Sporting News reported that Shibe claimed that the greatest value to the new ball was that it lasted longer.

Shibe might be remembered for his innovation, but his players remembered him for his generosity. Shibe was known to always take care of the ballplayers who helped his club to success. An example of this was in 1914, when Rube Waddell fell desperately ill. Shibe made sure that he was given the best available medical care to aid in his recovery, which, unfortunately, never came. Shibe’s kindness was one of his most attractive characteristics. Even when the American and National Leagues were still feuding, Shibe tried to put the squabbles aside for the good of the game. This was proven in 1903 when the Philadelphia Phillies needed their ballpark repaired. Shibe had no qualms with the club playing on the Athletics’ grounds. The press noted that John T. Brush would never have done such a thing for the American League.

Shibe’s life took a turn for the worse on August 21, 1920, when he was in a terrible car accident. He was in a car when a chauffer, David Smith, rammed into Shibe’s car, turning it over. Shibe never fully recovered from the accident and died in Philadelphia on January 14, 1922, nine days shy of his 84th birthday. He was buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. He left two sons, Thomas S. Shibe (who took over as president of the Athletics), and John D. Shibe, and two daughters, Mrs. Mary A Reach (she married A.J. Reach’s son) and Mrs. Elfreda MacFarland. His wife, Josephine, had passed away many years earlier. Benjamin Shibe died with a fortune estimated to be over one million dollars. Upon hearing of his death, American League president Ban Johnson remarked, “Ben Shibe was one of the founders of the American League and its greatest pillar. During his period of active participation the organization profited by his wise counsel, and his sterling integrity helped to a large degree to maintaining the game’s highest standard. There never was a man identified with baseball who commanded a greater respect. He has left an indelible stamp for good on baseball.”

This biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Ben Shibe clippings file: Baseball Hall of Fame; Cooperstown, New York

“President Ben Shibe of Athletics Dies.” New York Times January 15, 1922.

“Inventor of the Modern Baseball Cover has remained unknown.” Washington Post, October 11, 1908.

“Owners to Attend Opening.” Washington Post, January 24, 1909.

“Ben Shibe Injured.” New York Times, August 22, 1920.

“Shibe Park, Philadelphia, One of the Finest Baseball Fields.” New York Times, October 12, 1913.

“King Dooin is Dead!” The Sporting News, June 1, 1911.

“Waddell provided for by Athletics: Another Proof of Sentiment by Shibe and Mack.” The Sporting News, February 26, 1914.

“Baseball History Linked with the Life of Ben Shibe.” The Sporting News.

“Schedule is badly torn: Philadelphia accident hurts the National League.” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 16, 1903.

“Philadelphia Athletics new baseball $500,000 baseball plant which other baseball men will try to excel.” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 28, 1909.

Full Name

Shibe

Born

January 23, 1838 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

Died

January 14, 1922 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.