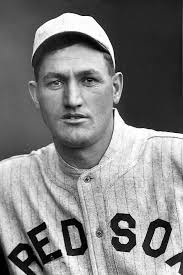

Ike Boone

Yeah, who needs a .300 hitter? Especially if you’re a perennially last-place ballclub. Outfielder Ike Boone hit .337 for the Boston Red Sox in 1924 and .330 the following year, with on-base averages of .404 and .406, respectively. The Red Sox finished in last place nine years in row, excepting only 1924, when they finished seventh instead of eighth. Might as well send this Boone guy back to the minor leagues, right? That’s just what they did.

Yeah, who needs a .300 hitter? Especially if you’re a perennially last-place ballclub. Outfielder Ike Boone hit .337 for the Boston Red Sox in 1924 and .330 the following year, with on-base averages of .404 and .406, respectively. The Red Sox finished in last place nine years in row, excepting only 1924, when they finished seventh instead of eighth. Might as well send this Boone guy back to the minor leagues, right? That’s just what they did.

Of course, it might be a matter of what you got in return, or the fact that offense isn’t the only thing American League teams looked for in the days before the designated hitter. “I could always hit,” Boone said.1 That was demonstrably true. He won batting titles in five different minor leagues. He had his shortcomings on defense, particularly when asked to play in an expansive outfield.

Ike Boone (Isaac Morgan Boone Jr.) was one of two brothers who played baseball in the majors. Brother James Boone, most often dubbed “Daniel” Boone, was a pitcher (25 months older than Ike) who appeared in 42 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, Detroit, and Cleveland, from 1919 through 1923. He posted a record of 8-13, with a 5.10 earned-run average. Ike and Dan crossed paths at the very end of the 1923 season, but never faced each other in a big-league ballgame.

Ike was born on February 17, 1897, in Samantha, Alabama. His parents, Isaac Sr. and Norma Lee (Sanders) Boone, farmed in Marcumville, also in Tuscaloosa County. At the time of the 1900 census, they had six children: George, Lucy, Wiley, James, Isaac, and Leona. Included in the census was 19-year-old Alexander McGee, a “servant/farm laborer” who was also described as “black.” (At the time of the 1910 census, McGee had been replaced by a “hireling” named William Allen, who was “white” and 24 years old.) Ike attended Gorgas elementary school and then four years at Guntersville High School, in the Alabama city of the same name.

Ike enlisted in the United States Navy in July 1918 and served as a seaman second class. Afterward, both James (Dan) and Isaac (Ike) attended the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa. The team won three consecutive regional championships and right after Daniel won the final game, over Louisiana, in May 1920, he went to join the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. Ike attended the university for only one year.

It was that same year that Ike started playing professionally as well. He played in the Georgia State League for the Cedartown Cedars, and hit for a league-leading .403 batting average with 10 triples and 10 homers. It was a Class D league, but he had earned himself a chance in Class A ball in 1921, signed to the New Orleans Pelicans. Indeed, when Hugh Bradley had been hurt in September 1920, Boone had “helped the Pels out in a pinch” by playing in a few late-season games.2 He’d played first base during the 10-game stint (batting .421);3 the Pelicans weren’t sure if they were going to use him there in 1921 or in the outfield. Boone was 6 feet tall and listed at 195 pounds. He threw right-handed, but batted from the left side.

In 1921 Boone played the outfield and played 155 games, hitting .389 and again leading his league. He homered five times but recorded an impressive 27 triples. He also stole 28 bases, another indication that for a large man he had some speed. An early March 1922 mention from the New Your Giants’ training camp in San Antonio (Boone had been acquired in September 1921) said, “Boone, who is no midget, is fast. He is a rugged type of player.”4 He’d actually weighed in at 207 pounds, which the Times said was “too much for him to carry. He is not fat, but still he could dispense with about twenty-seven pounds and not lose anything.”5 A week later the Chicago Tribune suggested Boone was “too ponderous to meet McGraw’s specifications.”6 Nonetheless, it was expected that manager John McGraw would take him North with the team. He did just that.

Boone hit .500 for the New York Giants in 1922, pinch-hitting in the games of April 22 at Brooklyn and April 26 at Cincinnati; he struck out the first time and singled the second time. That was his inaugural season in the major leagues – those two appearances. In early May he was optioned to Toledo. He hit .273 in 26 games for the Double-A Mud Hens and in late June he was sent to Little Rock, in the Class A Southern Association. There he hit .329 in 83 games.

The Giants placed Boone with the Texas League’s San Antonio Bears in 1923; the Bears were also a Single-A club. Boone played in 148 games and hit for a.402 batting average, enough to lead the league. He also led in RBIs, with 125. Boone had a league-record 35-game hitting streak during the season and his 241 base hits obliterated the Texas league record. He was one of five San Antonio players acquired by the Boston Red Sox on September 9, Boone being the one who was asked to report immediately after the Texas League season.

When Boone arrived in Boston, manager Frank Chance used him five times over four days, from September 18 to 21, pinch-hitting, and then playing three games in center field and the last of the five in right. He was unable to get a hit in his first three games, but was 2-for-5 in the second game of a September 20 doubleheader and then 2-for-3 with his only two runs batted in during a 4-3 win over the Tigers on the 21st, at Fenway Park. His second-inning triple drove in the pair of runs. He then scored on a single. Later in the game, with the bases loaded and two outs, he likely saved it for the Red Sox “by clinging onto the ball in the seventh inning after colliding so forcibly with [center fielder] Dick Reichle that Ike was stretched out stiff on the ground and had to be toted off the field and away to a hospital.”7 X-rays at Commonwealth Hospital proved negative but Boone’s left hip and shin were so badly contused that it was understood immediately that he would not be playing again in 1923.

He had arrived just too late to face his brother Dan, 25 months older, and who had pitched against the Red Sox in Boston on September 15. Dan had played in three 1919 games for the Athletics (0-1) and in 39 games for the Cleveland Indians from 1921 to 1923, concluding his major-league career with a record of 8-13 and a 5.10 earned-run average. In fact, Dan Boone was acquired by the Red Sox in a trade with the Indians on January 12, 1924. He was part of the deal that brought Bill Wambsganss and Steve O’Neill to Boston. He was placed with Mobile and was 14-13 with them that year. Dan Boone later converted to an outfielder and played in the minors through the 1933 season, though rarely above Class C.

Ike Boone played two full seasons for the Red Sox in 1924 and 1925, working exclusively in right field and, in his last 14 appearances in 1925, as a pinch-hitter for manager Lee Fohl. He hit a team-leading .337 in 128 games in 1924, and drove in 98 runs, just one behind fellow outfielder Bobby Veach. His 13 homers ranked him fifth in the American League, and were more than twice as many as anyone else hit on the seventh-place Red Sox.

Boone’s biggest day came on May 30, when he drove in seven runs, six in the first game (a 9-4 win over Washington) and one in the second, a loss. The Red Sox were in first place through June 13 but then continued to sink in the standings, finishing 25 games behind the Senators, a half-game out of last place.

Boone had not dropped weight. Indeed, the State Times Advocate of Baton Rouge had dubbed him “the biggest major league player in captivity.”8

The 1925 Red Sox as a team scored 639 runs, down almost 100 from 1924’s 735. Boone’s RBI totals dropped from 98 to 68. He was still second on the Red Sox, behind Phil Todt’s 75 RBIs. He hit for almost the same average, .330, as opposed to 1924’s .337. His on-base average was two points higher, .406 to the prior year’s .404, and Boone scored 79 runs, seven more than in 1924. There just hadn’t been as many baserunners on base for him to drive in.

The Boston Herald ran a charming photograph in its July 4, 1925, edition, showing Irma Boone with their two daughters, Norma and Nancy (age 3, shown scoring the game). The photo caption said they never missed a game at Fenway Park. Boone had married Irma Marie Golightly on February 22, 1921.

Why did Boone not continue with the Red Sox? Had he been a holdout, coming off two great seasons? Apparently not. Owned by the severely under-capitalized Robert Quinn, the Red Sox were a team teetering on the edge financially, and – while they were very pleased with Boone’s hitting, his defense was considered lacking. As the Boston Herald put it gently, “they have seen more nifty right-fielders than Ike.”9 Range was one thing, but he also made 13 errors, leaving him with a .941 fielding percentage.

There was meant to be a deal that traded Boone to Detroit, which would then work a deal to send Boone to Vernon, in the Pacific Coast League, but then a straight cash offer emerged and on January 21, 1926, his contract was sold to the Coast League’s Mission club of San Francisco for $7.500.10 The San Francisco Chronicle noted that this meant Boone had cost the Missions $32.50 per pound and, the following day, commented that they would have to order a special uniform for him.11 Indeed, the Missions had to order uniforms for all their players; it was a new ballclub, starting its first season, under owner William McCarthy, and prepared to try to make a splash.

Boone played in 172 games for Mission (the PCL had a much longer schedule than the major leagues), with 10 errors. He would have played longer but was struck in the face by a thrown ball during a double-play attempt on September 19 and suffered a season-ending compound fracture of the jaw. He’d started the season well, the only batter over .400 in late May. He hit 32 home runs. His .380 batting average placed him third in the league. He drove in 137 runs.12

On October 1 Boone was taken in the draft by the Chicago White Sox, with the Missions receiving only the stipulated $5,000 fee.

Boone didn’t play much for the White Sox, appearing in just 29 games, 11 of them in April. Early on, near the end of April, Edward Burns of the Chicago Tribune wrote that his weight had ballooned to 310 pounds. The story ran under a headline saying that Boone was “not as good as he was figured.”13 On April 29 he was operated on for appendicitis and was out until June 13. He had a seriously subpar year; he hit for just a .226 average, with 11 RBIs.

The White Sox dealt Boone to the Portland Beavers on November 5, part of a deal to acquire shortstop Bill Cissell from Portland. While riding a horse to the train station to head out for spring training, Boone fell off the horse and suffered a gash to the head, causing a delay of a few days.14 He was slow to get into condition, but was coming around, batting .311 by July 20, when Portland traded him to the Missions. Portland’s ballpark had a large outfield, which proved a detriment to Boone, who was unable to effectively cover so much ground.15 His hitting picked up in San Francisco, where he had been a very popular player and where he had hoped to land, and he finished the season with a .354 average. His next season was spectacular.

Boone played in 198 games for the Mission Reds in 1929, hitting a league-leading 55 home runs and for a batting average of .407, which also led the PCL. Boone also led in base hits, RBIs (with 218!), and total bases (553). The Mission team finished in first place, nine games ahead of the San Francisco Seals, but lost to the Hollywood Stars in the seven-game league playoff.

And he was off to an even better start in 1930. Through the first 83 games, Boone had already hit 22 homers and was batting an extremely impressive .448. On June 30 the Brooklyn Robins purchased his contract. His first game for Brooklyn was on July 6 and he was 2-for-4 with a home run and two RBIs. He hit safely in each of his first 10 games, and even played well on defense. By season’s end, he’d played in 40 games and hit for a .297 average, with three homers and 13 RBIs. And his fielding may not truly have been all that bad. He was, wrote Thomas Holmes of the Brooklyn Eagle, “a fairly sure catcher of a fly and had a strong throwing arm.”16

Though Boone was with Brooklyn the next two seasons, he saw very little action. He pinch-hit in six early-season games in 1931, walking once and getting one hit in five at-bats. After the May 23 game, he was released to Newark on option. Once again, he had tremendous success at the lower level of play, working in 124 games and batting .356 with 18 homers. Boone won the International League batting title, his .3561 topping Ray Pepper’s .3557.

In 1932 Boone again started the season with the big-league club. He appeared in 12 games, with 21 at-bats, but hit for only a .143 average. He drove in two runs, one each in the last two games he played in major-league ball. Boone played his final game on May 9. Five days later, he was released on option to Jersey City. He had finished his time in the majors with an overall .321 batting average in 356 games.

For the Jersey City Skeeters in 1932, Boone hit .320 and homered 16 times. The Dodgers sold the rights to his services on January 7, 1933. The Toronto Maple Leafs were the buyers; Toronto was a Detroit Tigers affiliate. Boone’s last four years as a player were with Toronto. He managed and was a regular in the Maple Leafs’ outfield in 1933 (batting .357), 1934 (.372), and 1935 (.350). The Maple Leafs were a Cincinnati Reds affiliate beginning in 1934. He was named International League MVP in 1934. In his last year, 1936, at age 39, Boone hit .254 and assigned himself work in only 71 games. They were Boone’s last games as a player. His (incomplete) career minor-league batting average was .321.

In 1937 Boone managed the Jackson (Mississippi) Senators, a New York Yankees affiliate in the Class B Southeastern League. He was the first of two managers. He had been meant to be a player-manager, and had wanted to play, but a bad leg prevented him from doing so. He submitted his resignation on June 8 so that Jackson could benefit from a playing manager in Jack Mealey.17

Boone then retired from baseball. At the time of the 1940 census, no occupation was reported.

From about 1952, he worked as head of the plant security force at a foundry in Alabama. He worked there for six years, until his death. He had previously worked in real estate and in some capacity with a cotton gin.18

In 1958 Boone was planning to fly from his home in Northport, Alabama, on August 2 to an old-timers’ reunion planned for Detroit. He was mowing his lawn the day before – on the 1st – when he suffered a fatal heart attack. He was survived by his wife, Irma, and their four daughters.19

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Boone’s player file and player questionnaire (completed by his brother J.A. “Dan” Boone) from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Brooklyn Eagle, March 15, 1932.

2 New Orleans Item, February 28, 1921.

3 Repository (Canton, Ohio), January 7, 1922.

4 New York Times, March 3, 1922.

5 New York Times, March 7, 1922.

6 Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1922.

7 Boston Herald, September 22, 1923.

8 State Times Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), March 15, 1924.

9 Boston Herald, January 12, 1926.

10 New York Times, January 21, 1926, and Hartford Courant, January 23, 1926.

11 San Francisco Chronicle, January 22 and 23, 1926.

12 The Oregonian (Portland), October 21, 1926, and Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1927.

13 Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1927.

14 San Francisco Chronicle, February 29 and March 2, 1928.

15 The Oregonian, July 21, 1928.

16 Brooklyn Eagle, January 8, 1933.

17 Biloxi Daily Herald, June 8, 1937.

18 As written by his brother Dan when he completed a questionnaire for the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

19 The Sporting News, August 13, 1958.

Full Name

Isaac Morgan Boone

Born

February 17, 1897 at Samantha, AL (USA)

Died

August 1, 1958 at Northport, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.