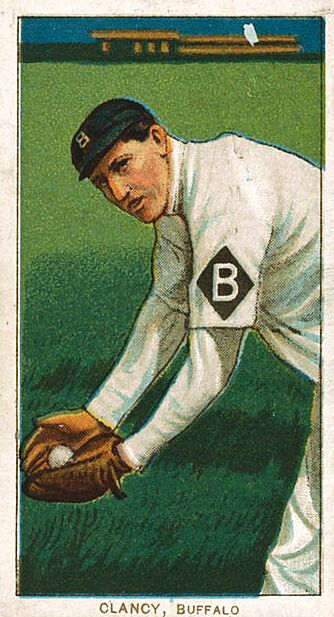

Bill Clancy

While many things about baseball have changed over the last century, the basic principles remain the same. For the fans: Baseball is a game; a distraction from their daily struggles. Fans are bound to their teams by passion, and perhaps some would say faith. For the players: Baseball is a means to a salary. In very few instances is a given player dedicated to his team beyond the length of his current contract. The player’s key concern is not the color of the uniform or the logo on the front of the jersey. The player is most concerned with the compensation that will ensure a quality of life for him and his family. This is not a modern phenomenon, as the career of Bill Clancy shows. Here is a player who was willing to sacrifice major-league stardom for financial gain.

While many things about baseball have changed over the last century, the basic principles remain the same. For the fans: Baseball is a game; a distraction from their daily struggles. Fans are bound to their teams by passion, and perhaps some would say faith. For the players: Baseball is a means to a salary. In very few instances is a given player dedicated to his team beyond the length of his current contract. The player’s key concern is not the color of the uniform or the logo on the front of the jersey. The player is most concerned with the compensation that will ensure a quality of life for him and his family. This is not a modern phenomenon, as the career of Bill Clancy shows. Here is a player who was willing to sacrifice major-league stardom for financial gain.

Clancy’s parents, John and Mary Clancey, were immigrants from Ireland (the “e” was lost somewhere between coastlines), having decided that farming would no longer support them in their native land. They established a homestead in Redfield, New York, a snowy town in upstate New York near Lake Ontario, and raised nine children, the first six of whom were girls and the last three boys. The youngest of all was named William Edward. His exact date of birth is a mystery of sorts. The 1880 Census states that William was 4 years old at the time of the census, making his year of birth 1876. Ancestry.com lists his birthdate as April 12, 1878. Retrosheet.org and Baseball-reference.com both say it is April 12, 1879.

In the 1890s, sometime around the age of 20 (depending on his true birthdate), William started to make his appearance on amateur baseball fields in the Utica, New York, area. His physical size was impressive: He stood 6-feet-2 and weighed 180 pounds. Despite his size he possessed speed. He threw right-handed and batted left-handed.

Clancy pitched and manned second base for a team in the town of Schuyler in 1896. In the spring of 1897 he pitched for the Whitesboro Anchors, and in the fall he saw action in the outfield for the Syracuse Shamrocks. He also played for the Utica Actives (1896 and 1898), the West Shore Clippers (1899), Potsdam (1900), the Weston-Mott Perfectos (1900), for whom he played third base, and Jamestown

With the Utica Actives in 1898, Clancy played right field. A teammate was future major leaguer Lewis Wiltse (Pirates, Athletics, Orioles, Highlanders, 1901-03). Clancy joined the Actives as a pitcher, but after having trouble with his control, he was made an outfielder and first baseman, and had much greater success; box scores show a high batting average and a knack for multiple base hits.

In 1901, while playing for the Jamestown team of the Independent League, Clancy started to attract the attention of major- and minor-league scouts. Teams in Buffalo, Ashtabula, Columbus, Rock Island, Rochester, and Ilion all stated an interest in him. Frank Dwyer, who was to manage the Detroit Tigers in 1902, expressed his interest. In the fall, Pittsburgh Pirates players on a barnstorming tour in upstate New York faced Clancy twice in games against a Johnstown team. In the first game Clancy played in the outfield; in the second game he played first base. His hitting and steady play impressed the Pirates. They recommended Clancy to the Worcester Hustlers of the Eastern League, and in 1902 the Hustlers signed Clancy, who played first base in 126 games and batted .292.

The Hustlers became the Riddlers in 1903. On July 21, with a record of 25-39, the franchise was moved to Montreal, to be known as the Royals. The move did little to improve the team’s standing, and it finished in seventh place, 57½ games behind the Jersey City Skeeters. (Rochester was eighth and last, 60½ games behind.) Clancy was the only shining star on the team, hitting .317. His work once again attracted the attention of major-league scouts. Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics offered him a contract, but Clancy turned the offer down, declaring that another year in the Eastern League would make him a more fit major leaguer.

In the early months of 1904 Frank Selee, manager of the Chicago Cubs, looking for an outfielder with a good bat and fast legs, drafted Clancy, but he refused to report, fearing that he would play only a utility role in Chicago. He negotiated with Montreal to play first base for the same salary the Cubs offered. Sportswriters began to believe that Clancy was not brave enough to join the ranks of the major leagues, and began to tag him with names like William the Chicken-Hearted. In an interview with the Utica Herald Dispatch, Clancy defended himself, stating, “All this talk about me having a yellow streak and being afraid to go to Chicago is rot. What is the use of going to the large league when I can get more money in the Eastern League? What I am playing for is the money. If I can get the money I want I will play ball anywhere, and if I do not I will play ball where I can get the best salary.”

Unfortunately for Clancy, Chicago’s draft of him was binding. If he didn’t report to the Cubs, he couldn’t play in the minor leagues. John Farrell, secretary of the National Association, the minor leagues’ governing body, suggested that if Clancy wished to play, he could join the outlaw Pacific Coast League. Clancy took the advice and jumped to Oakland. He reiterated his philosophy in an interview in the Utica Sunday Tribune: He did not play for health or glory, but for the salary. He refused to play for a manager who did not meet his salary demands, and he would sign where he could play on his own terms. In response, manager Selee told Sporting Life that Clancy did not have the “stamina necessary for fast company.”

But in May 1904, after playing ten games in Oakland, Clancy jumped the team. John Farrell announced that the purchase of Clancy’s contract to Chicago had been canceled, opening the door for his return to the Eastern League. The Toronto and Montreal teams competed to obtain Clancy’s services. Meanwhile, Sporting Life wrote of the player, “It appears that Clancy repeated his Philadelphia trick on Chicago. Fearful of his ability to hold his own, he signed with Oakland after accepting Chicago’s terms. With such a weak heart, Clancy never will make a successful major league player.” Clancy responded that when he went to Oakland he discovered that team owner Pete Lohmann was “the tightest man in the base ball business.” Clancy explained: “Pete was a good man, but he would only hand you thirty-five cents to buy a meal.” (Major-league teams at the time provided a $4-a-day food allowance.) Clancy said Lohmann once asked him to carry a bag for him, and Clancy replied, “Not on thirty-five cent meals!” Lohmann then bet Clancy a dollar that he couldn’t sell his release. It must have been bittersweet for Lohman when he had to pay Clancy his dollar after Montreal re-signed Bill.

Announcing Clancy’s signing with Montreal, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle wrote, “Bill Clancy the chicken-hearted had many chances to secure with the major league, but he does not want any of that game. He is a fast man in the minors.”

Meanwhile, Clancy left the West Coast to catch up with his new team in Newark. He was expected to be the backbone of the Montreal squad and boost the team’s standing. He was a fan favorite, and in June he was announced as the manager and was scouting talent to join his club. In 119 games he hit .310 for the Royals and led the league with 21 triples, but made 21 errors at first base and finished last among the league’s first basemen in fielding percentage.

Despite his reluctance to play for a major-league team, Clancy was still in demand in the summer of 1904. Frank J. Leonard, the manager of the former Worcester Hustlers, was organizing a baseball tour of Cuba, and Clancy was his choice to man first base. Leonard said of Clancy: “Bill is capable of delivering the goods in any league, and there are few faster men in the profession today than William.” Most of the players taking part in the tour were Eastern Leaguers, although there were a few major-league participants. In early October the steamship City of Memphis sailed from New York City to Savannah and then onto Tampa, where the team would stay for two weeks before heading to Cuba for three to four weeks. By all accounts the trip was successful, and Clancy was back in Utica in early December to spend the winter.

Also that summer, newspapers reported that Clancy had been drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates from Montreal. Then in September they reported that Clancy had been purchased by the New York Giants, and as Clancy prepared to sail south for the Cuba tour, they said he was expecting to join the Giants in the spring. But in December the Pirates traded first baseman Kitty Bransfield to Philadelphia, and manager Fred Clarke said Clancy “assures the press that he will surely play in Pittsburg the following season.”

Clancy reported to the Pirates’ 1905 spring-training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Manager Clarke advised him to avoid certain company and alcohol, telling him these associations have limited many a major-league career. Clancy seemed to have taken this advice seriously; as Sporting Life proclaimed, “Clancy is an ice cream soda fiend; he never drinks anything stronger.” Still, Clancy’s Montreal’s team expected him back from Pittsburgh, and planned to make him manager. But reports from spring training indicated that Clancy seemed intent on preventing that from happening. Sporting Life said his position on the squad seemed assured, and Clancy went north with the Pirates.

On April 15, in a game against Cincinnati, Clancy started a triple play by nabbing a popped-up bunt, stepping on first, and firing a throw to second before the runner could return. (The Pirates still lost the game, 7-0.)

On June 8, in a wild game against the Giants that featured an umpire being knocked cold by a pitched ball, a near-riot among fans over a hard slide at second, and a fire in the bleachers, an errant pitch by Red Ames pitch struck Clancy on the hand, severely injuring a finger. The injury was expected to keep Clancy out of the lineup for a month, but he was off the roster for only 10 days. He was back in action on July 1, but his batting suffered because of the injury. Soon after, Pirates officials caught Clancy drinking. Owner Barney Dreyfuss gave him a warning, and when Clancy was caught again, all of his early work was forgotten. Dreyfuss released Clancy to Columbus of the American Association but Clancy refused to go. National League President Harry Pulliam promulgated the release of Clancy to Rochester of the Eastern League. Clancy’s time in the major leagues was done. He had played in 56 games, batting .229 and compiling a fielding average of .983.

Before leaving the team, Clancy had a lasting effect on the Pirates. Clarke was looking for a new catcher, and Bill suggested the backstop of the Montreal club, George Gibson. Gibson played in the major leagues for 14 years, 12 of them with Pittsburgh, and managed the Pirates for six years in two separate stints. Meanwhile Clancy returned to a hero’s welcome in the Eastern League. A month after joining the Rochester Bronchos, he replaced George Smith as the captain of the team. Clancy celebrated by going 4-for-6 in a doubleheader with an inside-the-park home run. Meanwhile the Utica Sunday Tribune wrote that Clancy had offers from five teams for 1906.

Clancy spent the summer making plans for another postseason trip to Cuba. Frank Leonard had originally planned to take a team, but when he was unable to do so, Clancy took over the duties. In Pittsburgh he had been approached by a Mexican government official who requested that the team tour principal Mexican cities and promote the game by being the first American players to play in Mexico. Clancy funded the venture himself, believing that he could make a profit from the tour. The tour was expected to last three months, and was manned mostly by Eastern League players, but did include most notably Irving “Young Cy” Young of the Boston Americans. Jerry Nops of the Providence Clamdiggers, who had been the most successful American pitcher the previous year in Cuba, was to make the trip.

The trip was an utter failure. The team steamed out of New York directly to Cuba for the first leg of the tour. Cuban Abel Linares was to act as an agent and make arrangements for the Americans. The Americans had expected to play for fixed salaries, but upon arrival, Linares informed them that they would be only collecting a percentage of gate receipts. The series started with bad weather, and the Americans felt ill and played poorly in contests against the All-Cubans, Havana Reds, and the Fes. Fan turnout was low and gate receipts were much too small for financial gain. The Americans decided to cut the trip short and return home. Linares was asked to arrange for first-class travel home. Not only did he fail to see the travelers off, but the players found themselves in third-class steerage. Bad weather tortured the Americans on the way home, resulting in a trip 36 hours longer than intended.

Although Clancy continued to receive offers from major-league teams, he spent the next three years with Rochester. He was traded to Buffalo for southpaw Larry Hesterfer in 1908 after issues regarding pay disrupted his relationship with the Rochester ownership. In 1910 he played for Baltimore, and he finished his playing career in Fort Wayne of the Central League in 1911 and 1912. Those two years were the only times he completed a season elsewhere than in the Eastern League.

Clancy returned home to the Utica area to marry Helen Patterson of nearby Rome on April 19, 1914, at St. Peter’s Church in Rome. They became the parents of three sons, James, Bill, and Jack, and two daughters, Justine and Corinne. All of the children had an interest in baseball, with the boys playing at various levels. Clancy worked for the Rome Manufacturing Company Division of Revere Copper and Brass for several years, and also was a deputy sheriff in Rome.

Bill delighted in telling family and friends of his adventures in baseball. He liked to say that as a first baseman for the Pirates, his first responsibility was to catch the ball, and the second duty was to dodge the pebbles that followed the ball thrown by Honus Wagner. According to family legend, Clancy invited Wagner to be a parade marshal in Rome. Wagner accepted. The evening before the parade was spent at the Redfield Inn, where baseball stories were shared over drinks and laughter. Wagner gave a ball, glove, and bat to the Clancy boys, who played with them until they were completely worn out and discarded. A photo of Clancy and parade marshal Wagner riding in the back of an open automobile once hung in a stairway at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The photo’s location now is not known.

In an unattributed newspaper article estimated to have been written in 1940, Clancy discussed his thoughts on baseball at the time. He said uniforms had not changed much except that they had less flair. He said the “modern” game was less rough and less likely to be decided by a “trick.” The “modern” game, he said, was more of a business, and salaries were much more businesslike. In his playing days salaries were less than $1,000 a year. Current players “won’t listen for less than $5,000.” Clancy said he liked night baseball. At the time of the article he was neglecting his garden to watch the World Series.

Helen died on January 16, 1941. Bill died at home of a thrombosis on February 10, 1948. Their funerals were held in the church they were married in, and both rest at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Whitesboro, New York.

A few months after Clancy’s death, on June 27, he was among former professional baseball players from the Utica area honored by a civic committee.

Sources

Interview with Michael Clancy, grandson of William Clancy

Ancestry.com information, 1880 census, and an unattributed article provided by Michael Clancy

Baseball-reference.com was used to obtain player names and team information.

Fultonhistory.com was used to access historical New York newspapers including:

Utica Sunday Tribune

Oswego Daily Palladium

Syracuse Journal

Rochester Democrat and Chronicle

Utica Herald Dispatch

Utica Daily Press

Utica Morning Herald

Utica Observer

Albany Evening Journal

Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Binghamton Press

Paperofrecord.com was used for access to The Sporting News

La84foundation.org was used for access to Sporting Life, which provided most of the major-league information in this biography.

The youngest child of William Clancy, Corinne, died while this biography was being researched.

Full Name

William Edward Clancy

Born

April 12, 1879 at Redfield, NY (USA)

Died

February 10, 1948 at Oriskany, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.