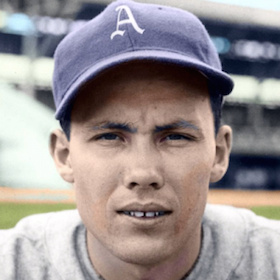

Bill Conroy

Catcher Bill Conroy was one of several ballplayers who found that World War II provided them the opportunity for a second shot at a major-league career that would otherwise have eluded them. He had played in one game for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1935 and another in 1936, then appeared in 26 games in ‘37. But that was it, until – after four years with Oakland in the Pacific Coast League – he was brought to Boston and played three seasons with the Red Sox.

Catcher Bill Conroy was one of several ballplayers who found that World War II provided them the opportunity for a second shot at a major-league career that would otherwise have eluded them. He had played in one game for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1935 and another in 1936, then appeared in 26 games in ‘37. But that was it, until – after four years with Oakland in the Pacific Coast League – he was brought to Boston and played three seasons with the Red Sox.

Conroy’s father, William J. Conroy, was a conductor on a steam railway, residing in Bloomington, Illinois. He and his wife, Eleanor (Gordon) Conroy, were parents to three children – Eugene, William Gordon Conroy, and a daughter named Jenna or June.

Bill was born in Bloomington on February 26, 1915. He listed his ancestry as Scotch-Irish and attended the Horatio G. Bent Elementary School in Bloomington, then Trinity High School, and a year and a half at Illinois Wesleyan University. He’d never played baseball at all until he was a sophomore in high school, but had played basketball and football.1 He was right-handed and his big-league height and weight are listed as an even 6 feet tall and 185-190 pounds.2 He said his nickname was “Con.”

Conroy started his career in professional baseball in 1935. He’d been given a tryout in July 1933, and was actually given the job of catching batting practice for the American League All-Stars in the very first All-Star Game, billed as the “Dream Game” at the time, but was injured when “his right hand was cut severely.”3 He told it later: “I was a 17-year-old kid still in school…Babe Ruth, the last batter in batting practice, fouled one off…The ball split open my right hand and I couldn’t catch again for five weeks.”4

In a 1934 exhibition game against Newark on August 31, he caught the full game, a 13-2 win for Newark; it was the first time the Athletics had played a night game.5

How had he first been discovered? A gentleman named Phil Haggerty scouted him during a 1933 game between Illinois Wesleyan and Bradley Poly of Peoria. Haggerty talked to Conroy and introduced him to Connie Mack the next time the Athletics were in Chicago. Conroy’s father accompanied him to meet Mack, and an oral agreement was struck. Conroy himself spent the rest of the season traveling with the team as a batting practice catcher both in 1933 and 1934.6

He signed with the team for 1935 and joined them for spring training in Fort Myers. An Associated Press report from early March said honors had been heaped both on him and shortstop prospect Lamar Newsome: “Both were said by observers to have shown decided progress in practice.”7 He was placed with Class-C Portsmouth (Ohio).8 He was also with Williamsport for 16 games, batting .196, but most of his time in 1935 was spent with the Richmond Colts in the Class-B Piedmont League, where he hit .307 in 36 games, with three home runs.

Still just 20 years old, Conroy was invited to join the major-league team in September, and caught in one game, his debut, in Washington at Griffith Stadium on September 21, the first game of a doubleheader. He caught the full game, a 4-1 seven-hit win by Johnny Marcum. A pair of third-inning errors by Athletics infielders cost Marcum a shutout. Conroy walked and hit a double in five plate appearances. Catching Marcum’s fastball was apparently quite something. A report in the Richmond Times-Dispatch later explained, “Conroy developed a badly swollen hand from receiving Marcum’s fire-ball and was relieved of duty for the rest of the season.”9

The day after Christmas, he married Gerarda A. Leyh.

In 1936 he again appeared in one game, but this time it was at the start of the season, on April 20, when the A’s hosted the New York Yankees at Shibe Park. He started the game and was 1-for-2, but it was a high-scoring game and Mack changed catchers midgame (Conroy had allowed three passed balls), with Charlie Berry coming in and getting an RBI single in his one at-bat. The A’s won, 12-11, on Chubby Dean‘s pinch-hit bases-loaded single in the bottom of the ninth.

On May 9 Conroy was optioned to Houston in the Texas League (Class A1), where he batted .298 with three home runs. On September 9 the A’s recalled him to the majors, but he saw no action. The glory days for the Athletics were over, though. After finishing first from 1929 through 1931, they finished last in 1935 and 1936.

Conroy was with the big-league club for 1937, and even caught their exhibition games in Mexico City against the “Mexico City Agriculture team,” as it was called in some of the American press. They played a number of teams –the “Necaxa club, Mexicans semi-pros”10 and the Comintra team, and then the Mexican Agrarians. Philadelphia sportswriter James C. Isaminger dubbed Conroy a “vastly improved man” that spring, adding, “It will be hard to keep him off the squad.”11

Just before the regular season began, Mack decided he didn’t need to carry three catchers, so Conroy was optioned to Williamsport. He played in 41 games and hit for a .239 average. Earle Brucker and Frankie Hayes shared catching duties for Philadelphia, but Brucker hurt his finger and Conroy was called up in time to get into the June 16 game. It took until July 10, the 14th game of his career, to record his first run batted in. By year’s end, he had three, and a .200 batting average in 67 plate appearances in 26 games. In 78 chances on defense, in 1935-37, he never committed an error.

In November he was one of a reported five players who were sent (in October and November) to the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks, in exchange for Dario Lodigiani. Red Smith characterized Conroy as “a big husky kid of some promise as a receiver, but at least a year or two away from the majors.”12

In 1938, Conroy played in 130 games, the most in a single season throughout his career, and hit .247. The team finished in last place, down from seventh in 1937. They got back to seventh in 1939 (Conroy played in 102 games, batting. 266) and to third place in 1940 (Conroy was .230 in 79 games; Billy Raimondi got more work), then fell to sixth in 1941. Conroy hit .290 in 89 games; Raimondi hit .293 in 97 games. The two were a catching duo.

Conroy was rarely in the headlines, though his 10th-inning single rated in the San Francisco Chronicle of June 3, 1939: “Bill Conroy’s Single Beats Seraphs, 4-3.” He also wasn’t a power hitter, homering 20 times over the course of the four seasons. One of those homers was on July 11, 1941, when he hit for the cycle in Oakland. Teammate Cecil “Dynamite” Dunn cycled in the very same game. Conroy remained a good defender, with 33 errors in an even 1,400 chances.

In the September 30, 1941, major-league draft, the Boston Red Sox selected one player: Bill Conroy. He was, wrote Ed Rumill, “a top-notcher in the minors. The Oakland club moaned at losing him for the draft price…It remains to be seen, however, whether he can hustle either Frankie Pytlak or Johnny Peacock out of a job.”13 Rumill thought he was maybe still a year away.

During the offseasons, Conroy enjoyed baking bread, cakes, and pies. He worked in his father-in-law’s bakery at Porterville, California.14

At the very end of February, the Sox got the news that Pytlak had been classified 1-A in the draft, and could be selected at any time. He enlisted in the Navy in April. This gave Conroy an opening and he showed pretty well in spring training, winning a March 16 game over Washington with a 12th-inning single and homering – again in the 12th – to beat the Cardinals on the 18th. It would be nice to report he made the most of it, and he did play in 83 games – but he only hit for a .200 average, with 20 RBIs. One of those RBIs was on June 13 when he drove in Bobby Doerr with the winning run in the bottom of the ninth (after striking out his first three times at bat). He finally made his first errors in the majors, and then made 10 more, but a .971 fielding percentage isn’t that bad. He was nonetheless second to Peacock in games caught.

Roy Partee took over as first-string catcher in 1943, with Peacock second and Conroy third. Conroy appeared in 39 games and hit .180, with only six RBIs, every one of which came in either a blowout or a loss. It simply wasn’t a very consequential season. The biggest headline he got was in July, when the Sox suffered through a 3-9 road trip: “Conroy Stands On Head in Gal’s Lap.” The Boston Globe‘s Roger Birtwell said that “among the highlights” of the trip was when “Bill stood on his head in a lady’s lap – in front of 13,000 people – and stuck there until an umpire, who probably was jealous, extracted him by means of a series of hard yanks at Bill’s left leg.” The “gal” was a “stunning, brown-haired cutie” and Conroy, who caught a foul popup, “landed headfirst in her lap [and] stayed stuck in the same position” for as long as a minute.15 There had been a game in 1942 (on June 25) when he’d snagged a foul fly off a lady’s hat; the lady was Mrs. Walter O. Briggs, wife of the owner of the Tigers.16

In 1944 he appeared in just half as many games – 19, driving in only four runs while batting .213. He had lost most of two months in midseason, breaking his right thumb in a June 19 exhibition game against the Bainbridge Naval Training Center (and the Red Sox lost the game, 5-2.) Partee and Hal Wagner handled most of the work. Conroy’s last two RBIs came one each, in his last two games as a major leaguer.

In October, Roy Partee was called to military service, and Hal Wagner was inducted as well. Conroy’s time came in January. He was taken into the Navy at San Diego.

The war was over in the fall and Wagner and Pytlak both returned; Conroy was also tendered, and signed, a contract for 1946. Bob Garbark, who had filled in during 1945, chose to retire. Conroy’s contract was purchased in April and he spent the ’46 season back in the Pacific Coast League with Sacramento. He hit .212 in 87 games. In 1947 and 1948, Conroy played in the American Association, traded to the Columbus Red Birds. He hit .224 and then .234. He was given his unconditional release in October. The Milwaukee Journal wrote, “Grandstand wolves in the Buckeye capital made life miserable for the slow moving catcher. He caught only when the club was away from home.” To which the Sacramento Bee’s Wilbur Adams added, “Conroy was not a particular favorite with Sacramento fans, either.”17

Thus ended Conroy’s pro ball career.

He worked as a supervisor of the driver salesmen of the Howatt Beverage Company in Alameda, California, and later as a technician for the Alameda County School District. He died at home in Citrus Heights, California, of congestive heart failure and other complications arising from diabetes, on November 13, 1997.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Conroy’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Pesky, Campbell, Conroy Are New Men With Boston,” Christian Science Monitor, April 3, 1942: 16.

2 Standard reference sources provide his weight as 185 pounds. On his player questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame, Conroy himself said his playing weight was 190.

3 Arch Ward, “Rick Ferrell Plays Through Game; Other Catchers Hurt,” Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1933: 27. See also “Alumni Defeat Coronado High,” San Diego Union, January 4, 1936: 14.

4 Fred Knight, “Merry Quips Fill Air When Red Sox Barbers Convene,” Boston Traveler, March 3, 1942: 24.

5 “Newark Stops Athletics,” New York Times, September 1, 1934: 9.

6 Bill Brandt, “Breaks of the Game,” unknown newspaper column datelined Pittsburgh, July 3, 1933. Clipping found in Conroy’s Baseball Hall of Fame player file. See also Bert Keane, “Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Team Not In Class with Flashy Cardinal Array,” Hartford Courant, march 12, 1936: 18. Conroy sported a gold baseball on his watch, a memento awarded to those who had been part of the All-Star Game. See John Drohan, “Pesky Gerts First View of Capital,” April 22, 1942: 23.

7 “Associated Press, “Connie Mack To Cut Work To One A Day,” Boston Globe, March 7, 1935: 20.

8 “White Sox Send Schlueter to Rock Island Club,” Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1935: A6.

9 Jimmy Jones, “Athletics May Send Billy Conroy Back to Colts Club,’ Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 5, 1936: 13.

10 Associated Press, “Athletics Lose in Debut,” New York Times, February 28, 1937: 80.

11 James C. Isaminger, “A’s Hit High Pitch in Mexico City Air,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1937: 7.

12 Red Smith, “A’s Deal for Lodigiani Bolsters Infield, Leaves Outfield Short,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1937: 1.

13 Ed Rumill, “Red Sox 1942 List May Change Within Fortnight: Deals Pending Most Valuable Pitching List,” Christian Science Monitor, November 27, 1941: 14.

14 The Sporting News, March 13, 1941: 8.

15 Roger Birtwell, “Conroy Stands On Head in Gal’s Lap,” Boston Globe, July 17, 1943: 18.

16 John Drohan, “Wagner Greatest Booster for Pitcher Tex Hughson,” Boston Traveler, June 26, 1942: 18.

17 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, January 20, 1949: 20. Adams quoted the Milwaukee Journal article.

Full Name

William Gordon Conroy

Born

February 26, 1915 at Bloomington, IL (USA)

Died

November 13, 1997 at Citrus Heights, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.