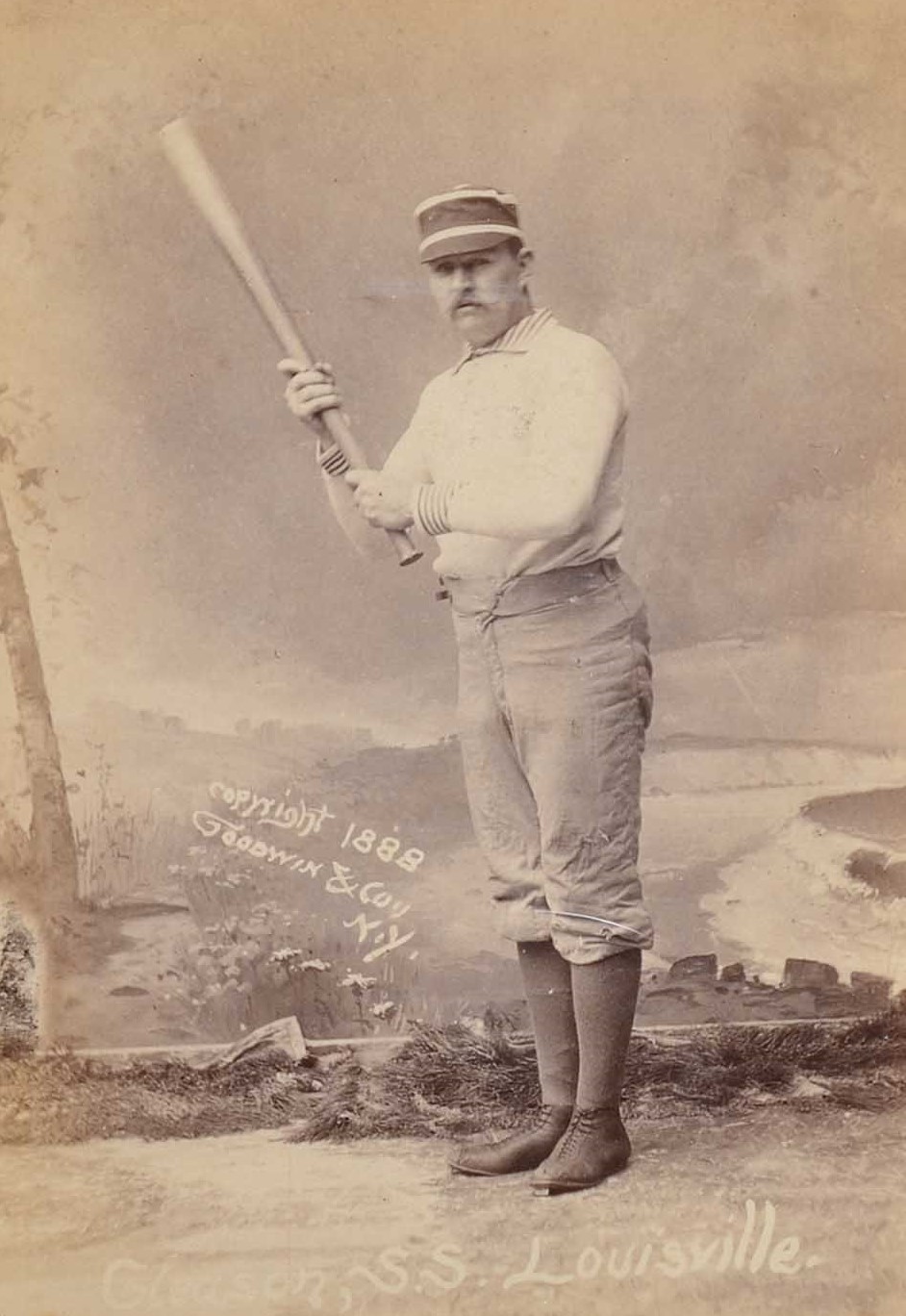

Bill Gleason

Bill Gleason is the younger of the two Gleason brothers who played on the inaugural St. Louis Browns team (the forerunner of today’s St. Louis Cardinals) in the American Association in 1882. Known as “Brudder Bill,”1 he covered shortstop for the Browns from their first season through their third straight pennant-winning season in 1887 and then finished his major-league career with a year in Philadelphia and a partial season in Louisville. After his baseball career, he went on to a long career with the St. Louis fire department.

Bill Gleason is the younger of the two Gleason brothers who played on the inaugural St. Louis Browns team (the forerunner of today’s St. Louis Cardinals) in the American Association in 1882. Known as “Brudder Bill,”1 he covered shortstop for the Browns from their first season through their third straight pennant-winning season in 1887 and then finished his major-league career with a year in Philadelphia and a partial season in Louisville. After his baseball career, he went on to a long career with the St. Louis fire department.

William G. Gleason was born on November 12, 1858, in St. Louis, four years after his brother Jack Gleason. His parents, Irish immigrants Michael Gleason and Ann (Day) Gleason, raised a total of six children (Philip, Jack, Bill, Margaret, Ellen, and Thomas) in their St. Louis home. Michael’s job as a laborer supplied their complete income until the children were old enough to go to work. William’s formal education was limited. He attended Webster grade school (no longer in existence), but it is not known how many grades he completed. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote in 1886 that he was exposed by an umpire as illiterate during an in-game dispute: “ ‘I can’t read and everyone in St. Louis knows it now,’ whined Gleason.”2

Bill and Jack were a pair of baseball stars. Jack typically played third base alongside Gleason at shortstop in an era when baseball teams lived and died by infield defense. They played for local semipro teams including the 1876 St. Louis Stocks and the St. Louis Red Stockings. Both brothers went to the League Alliance Minneapolis Browns in 1877. Gleason, along with brother Jack, played for the Peoria (Illinois) Reds for the 1878 season.3 St. Louisian Ted Sullivan, a future major-league manager, then recruited them for the Dubuque (Iowa) Red Stockings of the Northwestern League in 1879. With the Gleasons manning the left side of the infield, Dubuque won the league championship. In 1880 and 1881, they played on the best local semipro team, the St. Louis Brown Stockings.

Gleason married his first wife, Elizabeth Fay, in 1880. Soon their family grew with Philip in 1881, Catherine in 1883, Kathryn in 1884, and William in 1887. Catherine died in infancy but the remainder lived into adulthood.

Gleason was a volunteer fireman before he was a professional ballplayer. He joined the St. Louis Department in 1881 as a full time fireman. It was said in “The Summer of Beer and Whiskey” that his job was secured by Browns’ owner Chris Von der Ahe.4 In fact, the Post-Dispatch ran an item quelling a rumor that he and Jack planned to leave the fire department before the 1882 baseball season.5

The American Association was formed in 1882 to compete as a major league against the National League. Saloon and grocery-store owner Chris Von der Ahe owned the St. Louis entry, managed by Ned Cuthbert. Cuthbert took the 1881 Brown Stockings roster with a few upgrades and that became the St. Louis entry in the Association. Bill Gleason held down shortstop and played very well. He batted second all season, finished with the highest batting average (.288) on the Browns, and led Association shortstops in putouts and assists. But the Browns finished fifth in the six-team league with a 37-43 record.

Von der Ahe was not satisfied with a losing franchise. Like an early-day George Steinbrenner, he wanted a winner and wasn’t afraid to make changes to get one. He fired Cuthbert and hired local baseball pioneer Ted Sullivan, the Gleasons’ manager at Dubuque. Sullivan understood that the roster needed an upgrade and made changes, converting the Browns from an organization that used only local players to a group that contained the best players he could find from around the country. Shortstop Gleason remained a core component of his team.

Gleason played with an edge. Of course, baseball in the 1880s wasn’t as smoothly and legally played as it is in the twenty-first century. Baserunners were often impeded and middle infielders were in the perfect position to do it. There was only one umpire in a game and it was difficult for him to keep an eye on everyone when the play was going on. Even in this type of environment, Bill stood above his peers as an aggressive player. On scoring plays he would go after the catcher. (Once in 1882 he crossed his arms in front of his chest and slammed into Philadelphia Athletics catcher Jack O’Brien, knocking him unconscious.6) Gleason and teammate Charles Comiskey would coach first and third base, mostly so they move in close to the catcher and “subtly” remind him of his questionable ability and uncertain breeding.7 Actions like those eventually required baseball to place coaching boxes on the baselines.

Gleason was ready for the 1883 season right from the start. He never relaxed as evidenced by a play in the second game of 1883. He flattened Cincinnati catcher Phil Powers, scoring a run to bring the score of the game to 12-1, Red Stockings. The St. Louis fans loved it. He was always a fan favorite, as noted by the Post-Dispatch: “[He] is at the same time one of the especial favorites with St. Louis crowds, which fact is due not altogether to the fact that he is a local player. Gleason never played in a game in which he can be attributed with careless or indifferent work.”8

The Sullivan-built Browns were much improved in 1883. They were in a tight race with Philadelphia the entire season, finishing with a record of 65-33, one game behind the pennant-winning Athletics. The season was decided in a last series between the two teams with Philadelphia taking two of three. Gleason was involved in a very strange play in the first inning of the first game. With runners on first and second, Philadelphia catcher Jack O’Brien hit a sharp grounder to Gleason. He shoveled it to Joe Quest at second to start a double play. Quest dropped the ball and the Athletics’ Lon Knight rounded third and headed for home. Quest threw the ball to catcher Pat Deasley for the tag out. At the same time, Mike Moynahan went for third. Deasley fired to third baseman Arlie Latham but Latham missed the ball and Moynahan headed home. Gleason, backing up the play, grabbed the miss and threw to Quest, who relayed it to Deasley at home to tag out Moynahan and end the inning. Two different runners thrown out at home on the same play, one of the oddest double plays ever.9 For the season, Gleason was just as good as in 1882, playing every inning at shortstop and hitting .287. He finished second in the league in putouts and assists.

Gleason was an aggressive and effective baserunner and a wide-ranging fielder. The 5-foot-8 170-pounder was built solidly but was agile and had a strong right arm. The Post Dispatch noted before the 1884 season, “He plays deeper, takes more chances, and does more work than any other short stop in the country, and his work is telling and effective. He throws swiftly and accurately and has a perfect knowledge of tactic. …”10

The outlaw Union Association was formed before the 1884 season to compete against the National League and American Association. Henry Lucas, a St. Louis magnate, formed and financed the St. Louis Maroons, and they were the best financed team in the league. The Maroons tried to sign Gleason, but the existing leagues threatened to ban any player who jumped to Union Association teams so Gleason wasn’t swayed to play for them. Because Von Der Ahe payed comparatively high salaries to his players and was willing to increase their pay to keep them around, the Browns had nearly the same roster in 1884, finishing fourth in the pennant race, but with a very good 67-40 record. Gleason played in all 110 games, as did teammates Arlie Latham and Hugh Nicol. Gleason’s OPS, if it had been compiled at the time, would have been 15 percent higher than the league average.

In 1885 Von der Ahe finally got his wish, a pennant-winning team. Riding nearly full time on the arms of Dave Foutz and Bob Caruthers and with upgrades at catcher and in the outfield, they steamrolled to a 79-33 record, 16 games ahead of second-place Cincinnati. They were incredible at home, rolling up a major-league-record 27 straight wins, a record that still stood through the 2018 season. Gleason again played all 112 games but his offense declined to 6 percent below league average. However he did club a career-high three home runs. He was a core player and lineup fixture, having not missed a single league game since the 1882 season. In the era of no gloves and rough play, that was quite a feat for a middle infielder. At the end of the year, 250,000 St. Louisans turned out for a parade celebrating the team.11

Near the end of the 1885 season, Von der Ahe traveled to Chicago to negotiate with Chicago owner Albert Spalding a postseason series against the National League champion. This was the second time the National League and American Association champions faced off after the season, but the first time it was billed as the “World Series,” a term coined by St. Louis sportswriter (and founder of The Sporting News) Al Spink.12 The initial agreement for the series was for 12 games in eight cities over 18 days but the series was eventually shortened to seven games.

The series helped inflame the sporting rivalry between St. Louis and Chicago. The closely contested first game, in Chicago, was called because of darkness after eight innings, tied 5-5. The second game, in St. Louis, was very controversial. The single umpire, Dave Sullivan, made several calls that went against the Browns. For example, in a play early in the game, Mike “King” Kelly hit a sharp groundball to Gleason with a runner on third. Gleason muffed the ball and threw to first to retire Kelly instead of going to home. Sullivan, anticipating a play at home, wasn’t watching first and ruled Kelly safe. Observers agreed that Kelly was out easily. But the arguments here and in other cases were unsuccessful. In the sixth inning, a series of strange plays, including a ball that went foul but then curved back into fair territory, led to Chicago scoring three runs and taking the lead, 5-4. St. Louis fans became incensed, storming the field. The umpire was escorted out of the ballpark and back to his hotel by the security crew and the players left the field. Once Sullivan made it back to his hotel, he declared the game a forfeit in favor of Chicago.

The third game of the series went to the Browns, 7-4. The fourth game was a close affair, but the Browns won, 3-2, with Gleason scoring the go-ahead run on aggressive baserunning in the eighth inning. He made a wide turn at first to try to take advantage of a teammate being caught in a rundown between second and third. They were put out but the throw to first to retire Gleason went wild and he ended up at third. He then scored the winning run when Bob Caruthers hit a groundball to third base. The series then moved to Pittsburgh. Two games were played there in terrible weather, with the White Stockings taking both by identical scores of 9-2. Von der Ahe and Spalding had made a terrible mistake. The crowds in Chicago and St. Louis were very good but the games in Pittsburgh drew small crowds. The pair decided to end the series after the seventh game, in Cincinnati. That game proved to be anticlimactic. St. Louis triumphed, 13-4, when Chicago captain Cap Anson, ever the disciplinarian, benched his best pitcher (53-game winner John Clarkson) after he arrived at the ballpark five minutes late. The Browns had their way with Jim McCormick, who was effective the day before but clearly tired for game seven.

Modern chroniclers declare this World Series a tie, but contemporary newspapers and guides didn’t agree on the outcome. The Spalding Guide (predictably) ruled a tie but the Reach guide declared St. Louis the champion. The prize money was split equally between teams, but “Honest John” Kelly, the umpire for game seven, announced before the game that the winner would be the champion. It was a very exciting series for the fans in Chicago and St. Louis and helped set the stage for the 1886 season.13

The Browns’ league dominance continued in 1886. Gleason and company won their second straight pennant, 12 games ahead of second-place Pittsburgh. His offense bounced back to league average but he did miss two weeks early in the season with a leg injury. The White Stockings won the National League pennant to set up a World Series rematch. This time Von der Ahe and Spalding agreed to play all the games in St. Louis and Chicago and selected four umpires to try to avoid the umpiring controversies of the previous year. They finally settled on seven games in total, three in Chicago, three in St. Louis, and the final deciding game, if needed, in Cincinnati.

The first three games in Chicago were not close. Chicago won the first and third games 6-0 and 11-4 while the Browns took game two 12-0. The series then moved to St. Louis. During game four, Bill Gleason came to bat with the bases loaded and the Browns trailing 3-2. The hometown boy cracked a two-run single, putting the Browns ahead. Then in the eighth inning, he drove in two more with another bases-loaded single, putting the final runs on the board for the Browns’ 8-5 win. Game five went to St. Louis 10-3. Chicago was forced to use shortstop Ned Williamson as a pitcher because Clarkson had pitched three of the previous four games and their other pitchers were either injured or suspended. Chicago led the sixth game 3-1, but Arlie Latham hit a two-run triple in the ninth to tie the game, and the Browns won in the 11th on a wild pitch/steal of home.

Bill Gleason played all 135 games for the Browns in 1887 and the team won its third straight pennant, by 14 games over Cincinnati. However, his value as a player was definitely on the decline. In the twenty-first century, his season was calculated right at replacement level. Again Von der Ahe negotiated a postseason series, this time against the National League champion Detroit Wolverines. The teams repeated the 1885 error by negotiating a 15-game series played in various cities throughout the Northeast. Detroit easily won the series, 10 games to 5, often in front of small apathetic crowds in cold weather.

Von der Ahe was angered at his players’ effort in the 1887 World Series and angry that his profits were down. As he was wont to do, he decided to make some changes. Gleason did not go with the team on the postseason tour through the South, which may have also irritated Von der Ahe. The owner also wanted to trim some payroll so he traded some of his veteran players to other Association teams. Gleason and Curt Welch were traded to the Philadelphia Athletics for John Milligan, James McGarr, Fred Mann, and $8,000.

The 1888 Athletics were a good team, but they finished third, 10 games behind the first-place Browns. Gleason’s offensive game dropped off; he batted only .224 in 123 games. Still, after the season the Philadelphia Times wrote, “Gleason’s services have been invaluable this season, and he has probably won more games for the club than any other individual player.”14 The Athletics wished to re-sign Gleason but he refused, saying, “I like the city and the club but I do not like to sit on the players’ bench. If I am guaranteed a regular position on the team I would sign.”15 He remained the property of Philadelphia.

Gleason started the 1889 season waiting in St. Louis. In May Louisville started negotiating with Philadelphia to obtain Gleason. On June 1 he signed a contract to play for the Colonels. Louisville’s record at that point was 8-25, firmly seated in last place in the American Association.16 “The signing of Bill Gleason to play short is the most gratifying ball news that has been received in the city this season,” gushed the Louisville Courier-Journal.17 While Gleason did acceptable work with the bat, hitting .241 in 16 games, all those games were on the road and they were all losses. Then Gleason injured his hand in an exhibition game while trying to stop a hot grounder.18 The home fans never saw him play. This marked the end of his tenure, and the end of his major-league career, for one of the worst teams in major-league history. Louisville ended the season 27-111 but Gleason was long gone by then.

In 1890 old manager and friend Ted Sullivan talked Gleason into coming to Washington to play for and captain Sullivan’s Washington Senators in the minor-league Atlantic Association. He did, batting .260 while playing 79 games at shortstop. The club ran out of money in early August and disbanded. In 1891 Gleason umpired in one American Association game, Cincinnati at St. Louis on April 8, Opening Day. After many complaints about his decisions, he ended up forfeiting the game to the Browns with Cincinnati contesting the result. Two days later, the American Association removed Gleason as an umpire.19 Later that season Gleason became player-manager of the Rockford Hustlers in the Iowa-Illinois League. In 69 games he hit .330 and stole 20 bases as a 32-year-old veteran. That marked the end of his baseball career.

Gleason joined the St. Louis fire department as a paid employee. He enjoyed a 42-year career as a fireman, advancing from pipeman all the way up to captain of Fire Engine Company 28, not letting his lack of formal education hamper him.20 In 1901 he suffered a broken leg when the engine he was riding on overturned on the way to a fire.21

Gleason continued to attend games at Sportsman’s Park after retiring from baseball. In fact, he attended a game on the day of his second marriage, without his new wife accompanying him. He reminisced about the good old days and thought the pennant-winning Browns were one of the best teams ever, but he wasn’t a curmudgeon about the modern game. While attending a 1926 World Series game he commented, “… I’m not one of these old codgers who’d tell you there are no times like the old times. These boys out there are faster than we were, I think, and the game’s gone a long way ahead.”22

Gleason’s first wife, Elizabeth, died on June 21, 1902. Many years later he married Naomi Rogers in two different ceremonies. According to records, there was a marriage in the Lutheran church in Alton, Illinois, on June 27, 1931, and then a bedside Catholic ceremony held July 5, 1932, just two weeks before his death.

Gleason never shirked his duty even as he aged long past when someone would be a fireman. When he was 73, he was overcome by gas fumes during a fire at a Walgreen’s drug store on November 12, 1931.23 He contracted a throat infection while recovering from that injury. He returned to duty when able but during a fire shortly after his return, he stepped on a nail and his foot injury became infected. While recovering from the infection, he hobbled to a local drug store and collapsed from the St. Louis heat and humidity. He was brought home but died a few days later on July 21, 1932, the 29th St. Louisan to die from the heat that summer.24

There was significant controversy surrounding Gleason, his second wife, and his children after his death. Naomi was charged with arson shortly after Gleason’s death. It was alleged that she set fire to her home in order to collect fire-insurance money but the charge was thrown out in court. However, she did lose a civil suit against the insurance company and received no money.25 She attempted to cash in Gleason’s life-insurance policy but the insurer resisted paying, noting that he claimed to be 66 when the policy was written and he was actually well over 70. After two jury trials, her suit was thrown out and she received nothing, the jury having believed their first marriage license was forged.26 Gleason’s children were written out of his will shortly before his death in favor of his second wife. They sued her, claiming the marriage was invalid, but were unsuccessful in overturning his will. Gleason’s body was disinterred as part of the suit and an autopsy was performed but the cause of death (heat exhaustion and heart disease) was confirmed.27

Gleason is interred in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis (Section 17, Lot 260) alongside his first wife.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Ancestry.com.

newspapers.com.

Gilbert, Thomas. Superstars and Monopoly Wars (New York: Franklin Watts, 1995).

Notes

1 “Bean Ball a Cause of Howl,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 13, 1911: 7.

2 “Gleason Could Not Read,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 21, 1886: 5.

3 “John Gleason,” New York Clipper, December 30, 1882: 661.

4 Edward Achorn, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey (New York: Public Affairs Press, 2014), 14.

5 “Sporting Briefs,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 16, 1882: 2.

6 Edward Achorn, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey (New York: Public Affairs Press, 2014), 63.

7 Achorn, 85.

8 “Our Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 3, 1884: 9.

9 Achorn, 209.

10 “Sporting Briefs,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch: February 16, 1882: 2.

11 Jon David Cash, Before They Were Cardinals (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 107.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 “Base Ball,” The Times (Philadelphia), October 28, 1888: 14.

15 “Contracts for Next Season,” The Times (Philadelphia), October 26, 1888: 3.

16 “Louisville’s New Shortstop,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 2, 1889: 5.

17 Ibid.

18 “Notes,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 21, 1889: 6.

19 “Gleason Removed,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 10, 1891: 8.

20 “Fire Capt. Gleason, Once Noted Ballplayer, Dies,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 22, 1932: 2.

21 “Thrown from Hose Reel,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 16, 1901: 2.

22 Ibid.

23 “Fireman Killed, 14 Overcome, In Drug Store Blaze,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 1931: 3.

24 “Fire Captain Gleason Dies, Brings Heat Fatalities to 29,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 22, 1932: 6.

25 “Mrs. Gleason Loses Suit for Fire Insurance,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 29, 1935: 69.

26 “Mrs. Gleason Loses Suit for Insurance,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 29, 1938: 3.

27 “Fire Captain Gleason’s Body Is Disinterred,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 18 1934: 3.

Full Name

William G. Gleason

Born

November 12, 1858 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

July 21, 1932 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.