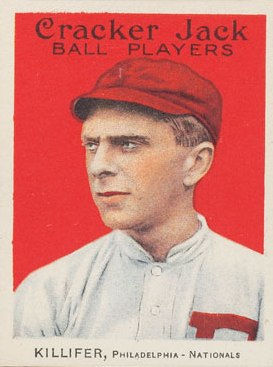

Bill Killefer

Bill Killefer began his 48-year career in Organized Baseball in 1907 as an unlikely professional, weighing only 125 pounds when he played with Jackson of the Southern Michigan League. According to his brother Wade, “the bats he used were almost as big as he was.” It would be years before he grew to be 5’10 1/2″ and 170 pounds, but along the way the skinny blonde youngster became one of the greatest defensive catchers of all time, playing over 1,000 games for the Browns, Phillies and Cubs. Pitcher Stan Baumgartner called him “smooth as silk with a natural intuition for calling for the pitch that the batter was not expecting.” He was death to ambitious base runners and, according to writer Frank Pollock, “possessed unerring hands and an arm so accurate it threw bulls-eyes.” Poised and clever behind the plate, Killefer was peerless as a field general and had the knack of getting the most out of his pitchers.

Dubbed “Reindeer Bill” for his speed afoot in his early years, fans of the Deadball Era remember him as one of “The Most Famous Battery in Baseball” with Hall of Fame pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander. He was also a high-profile newsmaker in January 1914 when he signed a contract with the Chicago Whales of the upstart Federal League while on the Philadelphia Phillies reserved list. A lifetime .238 hitter, Bill was not a great batsman, but he was capable of coming through in the clutch.

Sometimes described as a “player’s manager,” Killefer was a major league skipper for over 1,100 games with the Cubs and Browns and later guided minor league clubs in Sacramento, Elmira, and Milwaukee. According to Killefer’s philosophy, “The proper way to build up a club is to depend upon youth and speed.” One of the most popular figures in the game, Bill enjoyed teaching and was at his best with pitchers and catchers. Part of his legacy was the development of such receivers as Bob O’Farrell, Gabby Hartnett, Rick Ferrell, and Walker Cooper.

Baseball historian Peter Morris points out that, “between the day he faced Larry MacPhail in a high school ball game in 1905 and the day that he signed Larry Doby (the American League’s first Black player) in 1947, Killefer’s life intersected with an extraordinary number of the most influential baseball figures in the first half of the twentieth century.” Beside Alexander and the Federal League case, there was Branch Rickey and his farm system; the near strike during the 1918 World Series; Leo Durocher, Rogers Hornsby, and Bill Veeck. Others could be added to this list, including William Wrigley Jr. and Phillip Wrigley, Bill Veeck Jr., Charley Barrett, William “Uncle Billy” Disch, and George Stallings.

William Killefer Jr. was born on October 10, 1887, in Bloomingdale, Michigan. He was the youngest of four children born to William Killefer Sr. and Emma M. (Ferguson) Killefer. His ancestors were German immigrants named Kilhaver who came to Michigan by way of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and Pendleton, Ohio. Over the years, the Kilhaver name would evolve to Kilheffer, then change to Killifer, and finally become Killefer around 1918.

Bill’s grandfather, Henry Kilheffer, was one of two original settlers in Bloomingdale. Bill’s father, William Killefer Sr., was a Civil War veteran who returned to Bloomingdale in August 1865 and married Emma in June 1880. A year later, their first son Karl was born on June 24. Ola followed on October 10, 1882, and son Wade, known as “Red,” who also became a major league ball player, on April 13, 1885.

In 1888, the Killefer family moved fifteen miles south to the village of Paw Paw, where William Sr., went into the insurance business. In 1896, he was appointed postmaster of Paw Paw. Four years later he was appointed Justice of the Peace.

All three Killefer boys loved baseball and played whenever they had the opportunity. Though Bill and Wade played professionally, Killefer family lore holds that Karl was the best of them. Unfortunately, a tragic accident befell the family on October 12, 1895, when Karl was severely wounded while hunting, dying the next day.

After Karl’s loss, it was Wade who was the first Killefer to enjoy success on the diamond. He was the captain of the 1900-1901 Paw Paw High School team that romped to a 20-2 record and won the Michigan State High School Championship.

Wade “Red” Killefer was a professional baseball player and manager for thirty-six years, assembling a 467-game big-league career as a journeyman infielder and outfielder for Detroit, Washington, Cincinnati, and the New York Giants from 1907 to 1916. He had a lifetime average of .248. Wade also had a 798-game career as a player and manager with the Los Angeles Angels and Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League from 1917 to 1927, hitting .296. He was inducted into the PCL Hall of Fame as a player and manager in 1957. With five additional seasons managing the PCL’s Mission Reds and Hollywood Stars, plus another six years at the helm of the American Association’s Indianapolis Indians, Red compiled a managerial record of 1,940-1,800.

Bill duplicated Red’s championship feat during his junior year in 1904-1905. Paw Paw High School entered a late June tournament for the state championship and defeated Flint High School, 6-3, to win the school’s second state title. Bill was the starting catcher that season and had a .278 batting average.

Paw Paw High School again entered the state championship tournament during Bill’s senior year of 1905-06. Good fortune and the umpire, however, were not on their side as the Redskins lost a controversial 7-6 game in the semifinals to Ludington High School, which featured Larry MacPhail as their first baseman. According to Peter Morris, “The Paw Paw True Northerner published a letter from an anonymous and supposedly impartial observer claiming the umpire had deliberately favored Ludington. Years later, Killefer was still claiming that this was the only time he had seen a game stolen by a crooked umpire.”

Red’s first year as a professional was in 1906 with the Kalamazoo White Sox of the Southern Michigan League, where he started out as a catcher. He told his manager, Moe Myers, that his brother Bill “was a better than fair young catcher,” so Moe asked Bill to report late in the season for a workout. He wasn’t offered a contract immediately, but continued to practice with the club. When the season ended, Myers signed him for the 1907 season, but Bill told him he couldn’t report until June because he was going to college.

Bill Killefer played baseball in spring 1907 at Sacred Heart College in Watertown, Wisconsin. In a 15-10 loss to Marquette in May, the Watertown Daily Times noted that “a feature of the game was the superb playing of Killifer, the clever little backstop of the Sacred Heart nine. He secured four hits out of five times at bat and fielded an errorless game.”

Bill was also able to avenge the defeat that ended his high school career when he faced Beloit College and Larry MacPhail. With Sacred Heart leading 2-1 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, MacPhail came to the plate with two runners in scoring position. When the count reached two balls and two strikes, MacPhail was about to take a cut at the pitch when Killefer squirted a stream of tobacco juice into MacPhail’s eye and he took a called strike three to end the game. By the time he could see straight and protest, Killefer was long gone. When MacPhail hired Bill Killefer as a Brooklyn Dodger coach 32 years later, he introduced him to the press as “without a doubt the dirtiest player who ever lived.”

When Sacred Heart’s season ended, Bill returned to Michigan and reported to Moe Myers at Kalamazoo. Myers needed no players and sent him to Jackson, where he caught and played the outfield. Bill played in 29 games for the Convicts, hit .208, and earned $90 per month. At the end of the season he reverted to Kalamazoo and asked Myers to have the club advance him $50 so he could go to St. Edward’s College in Texas. Bill signed a contract for 1908, received his $50, and headed for Austin.

Bill Disch was the St. Edward’s baseball coach in 1908. A native of Milwaukee, Disch had coached at Sacred Heart College for two years and left Wisconsin for Austin in 1900. Over the years, Disch’s Hilltopper squads made a habit of defeating their cross-town rivals, the Texas Longhorns, who finally signed him to coach at the university in 1911. His teams went on to claim 21 conference championships, earning him the title of the “Grand Old Man” of Texas baseball.

When Disch first encountered Bill Killefer, he found a youngster who thought he knew more about baseball than his coach. Disch tried to teach him a different style of throwing to the bases, and Bill decided to quit the team. Disch and school officials called him on the carpet, and after several weeks of strenuous practice, Bill improved his throwing and frame of mind. In the final game between St. Edward’s and Texas near the end of the season, Killefer paced the Hilltoppers’ 8-4 win with a double, a triple, and two runs scored. Billy Disch’s last word on his protégé: “William was a wonderful ball player, but for a long time I thought he would never accomplish anything, for he was the most stubborn boy I ever tried to do anything with.”

In 2007, officials of St. Edward’s University took a fresh look at Killefer’s status as a student and concluded that after looking at “old yearbooks, school newspapers, and files… William Killefer was not enrolled at St. Edward’s at any time. Coach Disch was accused of using ‘ringers’ in a couple of articles that we ran across. We are assuming that Killefer was one of those ‘ringers’.”

Killefer’s play attracted the attention of the Austin Senators of the Texas League and Bill signed with them, receiving a $300 reporting bonus and a salary of $125 per month. He then sent $50 to Moe Myers in Kalamazoo, who gave him his release. A few days after making his Texas League debut, the Dallas Morning News noted Bill’s performance in a 3-0 loss to the Dallas Giants. Killefer was “death to ambitious baserunners… and threw out three at second.”

At this point, Bill had come to the attention of major league scouts; he had hit .222 in 65 games and had a .978 fielding average. American League clubs Washington, New York, and Detroit were all trying to sign him, but he was sold by Austin to San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League. Used primarily as a backup catcher, Bill made his Seals debut on August 13. The San Francisco Call said he “made a nice showing. He offers well at the ball and seems to be there with a nice peg to the second bag.” Hits, however, were few and far between, and Killefer was hitting a miniscule .068 on September 21. Bill’s offensive output picked up towards the end of the campaign, and his average for 26 games rose to .157. The Dallas Morning News concluded that Bill was “not quite up to class” in Class A company. San Francisco, which had paid $500 for him, sacrificed the money and let his contract revert to Austin.

With Austin unable to field a franchise in 1909, Bill was assigned to the Houston Buffaloes. In an amazing display of versatility, Bill played every position on the diamond except for pitcher as the Buffs cruised to the Texas League pennant. Called “Demon” by local fans, Killefer fielded an impressive .968, hit a personal high .244, and stole 32 bases. At the end of the season, Bill Killefer was named as one of two catchers on the All-Star Texas team by the Fort Worth Star Telegram.

One of Houston’s pitchers was a journeyman named Everett Hornsby. When the team visited Dallas and Fort Worth, Hornsby would take Bill home for one of his mother’s chicken dinners. It was there that Bill was introduced to Everett’s younger brother Rogers. Killefer gave the young man some used bats and balls, beginning one of the defining friendships of his career.

Bill’s passage to the big leagues was facilitated by legendary scout Charley Barrett, who was working for the St. Louis Browns in 1909. Charley’s first scouting trip was to the Texas League, where he spotted Bill Killefer. Barrett recommended him to the Browns, and his contract was purchased. Bill was the first of hundreds of players that Charley Barrett scouted and sent into professional baseball.

Bill Killefer had an inauspicious major league debut on September 13, 1909, against the Detroit Tigers. With no instructions from manager Jimmy McAleer, Bill and pitcher Chuck Rose got walloped 10-2. After a series in Washington where Bill and his brother Red faced each other, his season ended in New York on September 30 when his collarbone was broken by a foul tip. Despite batting and fielding averages of .138 and .905, The Sporting News gave him a positive review: “No receiver in the entire base ball arena, either major or minor leagues, has anything on this fellow as a thrower to boxes. He is handicapped, however, by extreme youth….With another year’s weight on him, Killifer is destined to some day rank with the game’s great catchers if he takes the proper care of himself.”

Bill reported to the Browns 1910 training camp in Houston and showed that he was “long on pep and short on silence.” His performance caught the eye of one scribe, who called him “slight but fast, promising, young, intelligent, and ambitious.”

Unfortunately, the Browns’ season was a disaster, culminating in an abysmal 47-107 record and a last place finish, 57 games behind the pennant winning Philadelphia Athletics. Bill continued to fail at hitting, posting an anemic .124 average in 193 at bats. His fielding was also a liability, with a league-leading 29 errors and a .938 fielding average. Most of the miscues were on wild throws.

When the St. Louis Browns visited Hot Springs, Arkansas, for their 1911 spring training, Bill Killefer reported for workouts with the hope of landing the starting catcher position. Instead, new skipper Bobby Wallace released him to the Buffalo Bisons Eastern League team in early April. Buffalo’s manager was George Stallings, who was returning to the team after a four-year absence. Stallings, a plantation owner from Haddock, Georgia, later became known in 1914 as “The Miracle Man” for leading the Boston Braves to a World Series victory after being in last place in mid-season.

With Buffalo, Killefer became “a graduate of the George Stallings school…. he put the young man through an educational course that rapidly made him a good, finished backstop. His hitting also improved remarkably…. he swatted the bulb for .251, the best average he ever made. He was a great thrower and pegged to bases with the speed of a rifle bullet.”

On August 19, Bill Killefer’s contract was purchased by the Philadelphia Phillies. His start on October 3 against the New York Giants in Philadelphia would prove to be significant. Grover Cleveland Alexander was on the mound, and it would be the first of 250 times that Alex and Bill would be the starting battery in big league games. On this date, the Giants won 12-3, lashing ten hits and eight runs in Alexander’s 5 1/3 innings. Killefer was hitless in two at-bats and completed a double play in the third inning on a strike-out-throw-out. Bill’s Philadelphia audition yielded a .188 average in 16 at-bats and a .975 fielding average.

In November 1911, a squad of Phillies left Florida by steamship for several weeks of barnstorming in Cuba. Bill Killefer was the team’s catcher. Nine games were played against the Almendares and Habana clubs, with Philadelphia winning five of the contests. Bill’s position with the Phillies was solidified by his performance, which included a .242 batting average. According to one review, “Killefer is full of pep and injects a lot of this very valuable stuff into his pitchers. He was the hit of the Cuba trip in 1911. His pepper on the ball field had them all looking his way.”

The 1912 Phillies entered the season in dire need of catchers and held open auditions for the position. According to Grover Cleveland Alexander, “Some of them were terrible… Finally they had to let Killefer try his hand. And when they let him get in there they never could get him out. Bill Killefer was the greatest catcher I ever worked with or ever saw any other pitcher work with.” Alexander and Killefer immediately meshed as a battery and became best friends off the field. “I worked my best with Killefer,” said Alexander. “He understood me and knew how to handle my peculiarities.”

Bill was injury prone during the early part of the season, breaking his right hand in the second game of the season on April 12. He was back the second week in May and promptly got hit in the ear by a foul ball in Cincinnati, causing him to leave the game. Later in that series he was beaned. In late May, Bill again broke a bone in his right hand, and it would be June 14 before he returned to the lineup. By early August, he was doing nearly all the catching, prompting TSN to comment: “He has shown his class behind the bat and he has also demonstrated that the coaching which he has received has increased his batting efficiency to a marked extent. Killefer came here with the reputation of being a weak batsman, but of late he has been hitting the ball at better than a .300 clip.”

The Phillies finished 1912 in fifth place. Bill Killefer had caught 85 games, hit .224, and fielded .975, improvements over his previous 91 games in the majors when he hit and fielded a cumulative .130 and .937.

In mid-December, Sporting Life reported that “Catcher Killifer, of the Phillies, has purchased a half interest in one of the best known real estate firms in Kalamazoo, Mich. not for the purpose of quitting base ball, but to prepare the way for a permanent business when his ball playing days are over.” In January 1918, TSN mentioned that Bill was engaged in business with his uncle, Robert Killefer, a pioneer designer and manufacturer of soil-tilling farm implements.

The August 1913 TSN published a photo of Bill and described him as a prototype of a new breed of catcher. “The time has gone by when the ideal catcher was considered a mountain of beef and bone….The catcher now is more than a mere backstop, inserted to break the impact of pitched balls against the grand stand planks. Bill Killifer of the Phillies is an illustration. The St. Louis Browns disposed of him because he was considered too light for catching, but now he is doing the bulk of the work for the Phillies….The old iron man has given way to the more delicate structure of steel and Killifer is one of that sort, built on graceful lines, but able to give and take with the best of them.”

A new statistic tracking base stealers thrown out by catchers surfaced in December 1913. The results showed Bill Killefer leading the National League by throwing out 130 base stealers. Bill’s manager, Red Dooin, said, “Everything considered, Killefer is the best catcher in the country. He can throw, hit, run the bases and receive and he has a great head. Jimmy Archer, whom many pick as the leader of the class, is behind Bill as a receiver, for he squats in one spot, while my youngster shifts his feet, goes in the air after a ball and in general is as agile as a cat.” Bill finished the 1913 campaign with a .244 average, and a .988 fielding average.

On January 10, 1914, newspaper headlines loudly informed the sporting public that Bill Killefer and three others had signed contracts with the Chicago Whales of the Federal League, a six-team “outlaw” circuit that had operated in 1913 with enough success that President James A. Gilmore wanted to continue the enterprise. Whales owner Charles Weeghman enticed Bill with a contract offer of $17,500 for three years, a figure that dwarfed his previous year’s pay of $3,200. On January 18, Killefer denied signing a contract with the Feds, leading Weeghman to tell the press that not only had Bill signed, but had also accepted $500.

It wasn’t long before Killefer began to have second thoughts. He maintained that the Federal League gained his contract under false pretenses, asserting that twenty other stars had signed. After Billy Shettsline, business manager of the Phillies, offered him a new contract, he decided that he had made a mistake by signing with the Feds. Bill’s tenure with the Whales had lasted but twelve days. He signed with the Phillies for $19,500 for three years and sent the $500 back by registered letter to Weeghman, who refused to accept it.

Federal League attorney Edward E. Gates soon filed a lawsuit against Killefer and the Phillies seeking an injunction to prevent Killefer from playing for Philadelphia during the 1914 season. On April 9, Judge Clarence W. Sessions of the U. S. District Court in Grand Rapids, Michigan, denied the request, ruled that both parties in the dispute had “unclean hands,” and said that Killefer “is a baseball player of unique, exceptional and extraordinary skill and experience. Unfortunately the record also shows that he is a person upon whose pledged word little or no reliance can be placed and who for gain to himself, neither scruples nor hesitates to disregard and violate his express engagements and agreements.”

The Sporting News editorialized that Killefer was “due for a spanking… In signing with the Federals before negotiating with the club which is entitled to his services by every law of baseball, and then flopping back to the latter, after he had been coddled like a ten-year-old child, is laughable to behold.” On April 13, the Baseball Player’s Fraternity expelled Bill for “contract jumping.”

The Federal League’s appeal of Judge Sessions’ ruling was denied on June 30, and the Killefer case was finally over. Bill was legally free to play for the Phillies, which he was already doing. Judge Sessions’ ruling had the effect of leaving baseball’s reserve clause intact.

Peter Morris maintains that there is another element in play here. “It’s very clear to me that the way Wade Killefer was bounced around from the majors to the minors was a very large factor in Bill’s decision to jump to the Feds.” In regard to TSN’s commentary about Bill Killefer being due for a spanking, Morris observes that, “perhaps Killefer deserved the harsh words, but he would spend the rest of his life belying the characterization by proving himself to be a player whose value to his team greatly exceeded his individual statistics. Indeed the bidding war for his services itself illustrated that fact, since at the time of his court case Killefer had a .207 lifetime average and one career home run.”

In 1915, the Phillies rollicked their way to an 11-1 start with Bill and Grover Cleveland Alexander locked into a dominating groove to form, in the words of Jimmy Isaminger, “a super-human battery.” This would be the first of three straight 30-win seasons for Alex, who also pitched twelve shutouts. The duo was also solidifying a reputation as “the greatest catcher-pitcher combination of their era… Old ballplayers will tell you that Alexander and Killefer would often work an entire game without exchanging signals. ‘You know these ginks can’t hit,’ Bill would tell Alex before a game. ‘You just throw ’em and I’ll catch ’em and we’ll get outa the park early today.’ Both men were quiet cool, seemingly nerveless.” Bill and Alex were so consistent with dispatching opponents that Philadelphia fans would often say “let’s go out to the park and watch Bill and Alex shut them down in an hour and a half.” When he was with the Phillies, Alex “always pitched on Saturdays so that he could put the team on ‘the 5:10 train for Atlantic City.’ In those days there was no Sunday ball in Pennsylvania and immediately after a Saturday game the Phillies would go to the seashore. Alex never missed putting the boys on that train.”

On September 7, in a game at Brooklyn, Bill injured his shoulder, his arm “went dead,” and he had to leave the game. A specialist examined him, but nothing could immediately be determined. When the shoulder didn’t improve, Killefer visited “Bonesetter” Reese for treatment, but the arm and shoulder didn’t respond. Fortunately for the Phillies, Eddie Burns filled in at catcher and the Phillies were able to win their first pennant by 7 games over Boston. As the World Series against the Boston Red Sox approached, it became increasingly unlikely that Bill would be able to play.

Bill Killefer attempted to warm up before the first game of the World Series but was in no shape to play. He made a cameo appearance as a pinch-hitter for Eppa Rixey in the bottom of the ninth inning of the last game, grounding to shortstop for the last out of the series.

Entering 1916, the Phillies’ major offseason concern was the condition of Bill Killefer’s arm. By the time spring training rolled around, Killefer was being limited to light workouts, no hard throwing, and no game action. When the season started on April 12, Eddie Burns was behind the plate, and Jack Adams had been signed as a backup. By May 1, Bill was put on the disabled list to make room for an outfielder, but the roster move didn’t last long because Adams was injured and Burns had an old wound reopened in a game at Brooklyn and was expected to be out for a month.

Almost in desperation, manager Pat Moran decided to give Killefer a try, and Bill made late-game appearances against St. Louis on May 10 and 11 and was back in the starting lineup on May 12. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted that, “upon the return of ‘Reindeer’ to his old post… the team showed an immediate improvement and started on a rampage that completed their fine road record in spite of the bad beginning.” By June 3, the Alexander and Killefer battery had fashioned four shutouts in three weeks and the Phillies had vaulted into third place.

With 91 wins for the season, the Phillies had one more victory than they had when they won the pennant in 1915, but the 1916 team finished second. Bill Killefer led the league’s catchers in fielding percentage at .985 in 91 games behind the plate. In sizing up the possible post-season catching staffs, Hugh Fullerton said, “Killefer is not the backstop he was a few years ago. His arm, while it came back to a large extent, is not as strong as formerly.”

Contract issues again plagued Bill Killefer in 1917. At the end of January, the Hartford Courant reported that Pete Alexander had demanded a $15,000 annual salary and a three- year contract from Philadelphia. Alex also told the newspaper that management wanted Bill to take a $2,000 pay cut to $4,500 for the coming year. Furthermore, the pair had made a compact to hold out together in their dealings with the club. If they were not satisfied with the offers, they would play with semi-pros during the season. Standing firm, Bill rejected the $2,000 cut and told reporters that he and Alexander would be checking with each other before doing any business.

Although Bill eventually signed a contract, a major issue existed between Bill and club president William Baker, who was upset that Killefer had caught only 91 games in 1916. “‘You can’t catch a whole season,’ Baker said. ‘Make that raise in the form of a bonus for $1,000 and I’ll show you I can catch the whole year,’ responded Killefer. According to Killefer, the president of the club agreed to the bonus, but the pact was not made in writing.”

Killefer had one of his finest seasons for the second-place Phillies of 1917. He led National League catchers in fielding average with a .984 mark, as well as in putouts, double plays, and total chances per game. Best of all, he made a major contribution with his bat, hitting a (so far) career-best .274, good for 23rd in the league. One honor for his stellar work was being named as one of two catchers, along with Ray Schalk, on the All-American Baseball team. After the season was over, manager Pat Moran said “I regard Bill Killefer as one of the greatest catchers the game has ever produced.”

On October 8, 1917, Bill married 29-year-old Margaret Smith Thorp at her South High Street home in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The couple would have three children– Jane, William, and Margaret Ann.

By virtue of his marriage to Margaret, Bill Killefer gained a baseball brother-in-law, Boston Braves manager George Stallings, who had married Margaret’s sister Bertha, the widow of former big leaguer Bud Sharpe, in May 1917. Sharpe, who had also played for Stallings at Buffalo, later became manager of the Stallings’ Georgia plantation, where he and Bertha made their home. Sharpe died of a heart attack on May 31, 1916, at age 34.

On December 11, 1917, President Baker of the financially strapped Phillies astonished the baseball world by trading Pete Alexander and Bill Killefer to the Chicago Cubs for pitcher Mike Prendergast and catcher William “Pickles” Dillhoefer and $55,000 in cash. At the time, it was the biggest trade in baseball history and, as time has passed, it is still one of the most lopsided. A day after the trade was completed, Bill told the Chicago Tribune that he was “elated at the opportunity of playing with Chicago… I do not know of another city I would rather play in. President Weeghman and Manager Mitchell are real sportsmen. I am jubilant over the change.” According to Peter Morris, “The continued interest in Killefer by the one man who might have held a grudge [Weeghman, who tried to sign him in 1914] is an important indication of the high esteem with which Bill Killefer was regarded.”

In January 1918, Wade Killefer told TSN that Bill was talking about retirement. Bill’s friends did not take this retirement threat seriously and speculated that he was waiting to see if Pete Alexander was given a signing bonus, which would open the door for Bill to make the same request. This dance routine went on until February 19, when he announced that the Cubs contract was satisfactory and he would play at least another season.

With the United States now heavily involved in World War I, the 1918 baseball season was overshadowed by the military’s personnel needs and ballplayers were told that they must “work or fight.” On April 16, Bill was notified that he was placed in class 1 by the Kalamazoo draft board, and it seemed likely that he would be pressed into service soon. Alexander was the first to get drafted after pitching only three games.

The Chicago Cubs took hold of first place on June 6. The Chicago Tribune was effusive in evaluating Reindeer’s value: “Killefer has ‘made’ the Cubs… and has strengthened the Cub pitching staff more than Alexander could have… Alexander could have pitched only once every four days. Killefer is in there every game, making better pitchers than they were before out of all of Mitchell’s slab staff. Killefer is unquestionably the best catcher in the National League… the north side club owners were more to be congratulated on obtaining Killefer than on getting his more famous battery mate.”

With the U.S. government ordering Major League Baseball to conclude its regular season by Labor Day, the Chicago Cubs, a fifth-place team in 1917, won the National League with a record of 84-45. Bill posted a .233 batting average and led the league’s catchers with a .982 fielding average.

The Cubs faced the Red Sox in Chicago on September 5 for Game 1 of the 1918 World Series, and Babe Ruth tossed a 1-0 shutout. The Cubs took Game 2, 3-1, doing all their scoring in the second inning, with Killefer’s RBI double and Lefty Tyler’s two-run single. Boston was victorious in Game 3 by a 2-1 count. In Game 4, Bill Killefer scored the 8th inning run that ended Babe Ruth’s World Series scoreless innings streak at 29 2/3, which dated back to 1916.

A serious dispute involving the players’ share of World Series money erupted prior to Game 5 in Boston. The National Commission, with dwindling series attendance, changed the formula for distributing the cash to $1,200 for the winners and $800 for the losers. Members of the two clubs conferred, vented, and planned a strategy– to confront the National Commission and demand full shares. Bill Killefer was one of four representatives who met with the commission and proposed a compromise of $1,500 for the winners and $1,000 for the losers. The Commissioners listened but offered no promises.

As Fenway Park filled up prior to Game 5, the irate players chose to forego warm-ups and remained in the clubhouse. As the crowd began to grow restless and extra police were called in, the player representatives and the Commission met again in a room under the stands. The Commission didn’t yield to the players’ appeal. Finally, the players withdrew their demands and it was announced to the crowd that the players had agreed to play in recognition of the public’s loyalty and for the good of the game. Hippo Vaughn pitched for the Cubs, who won 3-0 as the Cubs stayed alive for another day. The shutout was typical of Vaughn, who had a great year in 1918, leading the league with 22 wins, 148 strikeouts, and a 1.74 ERA. Manager Fred Mitchell said Vaughn was as good a pitcher as Grover Alexander in his prime, with Bill Killefer being “the real man in the making of both pitchers.”

The Series ended on September 11 when Boston’s Carl Mays beat the Cubs, 2-1. Although Chicago’s pitchers allowed Boston only nine runs in the six games, their offensive attack was weak, producing only 10 runs, of which six came in their two victories. Killefer hit .118, with 2 runs and 2 RBIs.

On September 14, Bill Killefer reported for duty with the U.S. Army at Camp Custer, Michigan. He was assigned to clerical responsibilities, mostly handling the paperwork of men who were being mustered out of the service. He was honorably discharged on February 23, 1919, and returned home to Paw Paw to rest before reporting for spring drills.

In early April, manager Fred Mitchell named Bill team captain, saying that he deserved the honor because of his splendid work helping the Cubs to win the National League championship. Pete Alexander joined the Cubs just in time for Opening Day but needed two weeks to get back on the mound. Things did not go well at the beginning and then got worse, and by the end of May he was 0-4. Other factors were also at play. “I always thought that Alex was a changed man after the World War,” Bill observed nineteen years later. “Before he went to France he was more or less careful about his drinking, but when he was demobilized he would drink anything and at any time.”

Bill Killefer had his finest statistical season in 1919, hitting a career-high .286 and posting a National League best fielding average of .987. He also led senior circuit catchers in putouts and assists.

The 1920 season found injuries beginning to take a toll on Bill. On July 3, in the fifth inning of a game at Cincinnati, a foul tip off the bat of Heinie Groh broke a wire in his mask and cut a gash in his forehead. Another foul tip broke his right index finger in a game at Brooklyn on August 9, and he did not play again that season. The finger still troubled him after the 1920 season ended, and it was operated on in Chicago on October 30. After another examination in late November, Bill felt better and expected to play again in 1921. The Cubs had ended the season four games under .500 and tied for fifth place with St. Louis. Fred Mitchell was released as Chicago’s manager in November and was replaced by John Evers. Due to his injuries, Bill Killefer had caught in only 61 games, with the bulk of the backstopping duty falling on Bob O’Farrell.

In 1921, Bill Killefer’s body was breaking down from the cumulative effects of catching 1,000 games in the majors. The Chicago Tribune’s I. E. Sanborn continued to call him “the best man in the league” at catcher, but Bill could not elude “the jinx which pursued him last season” when he was not able to play on April 13, Opening Day, because of a sprained throwing hand. He was on the disabled list for three weeks. Bill was able to take advantage of the lively ball and continued his hot hitting through June and early July, posting a .391 average by July 5. The rest of the club, however, wasn’t doing as well, and the Cubs were slogging along in sixth place. On July 15, the Chicago Tribune announced that Killefer had a sore shoulder and would be out of the lineup for a few days.

On August 3, Johnny Evers was fired as manager by team president William Veeck Sr. and Bill Killefer was named player-manager, becoming the youngest manager in the National League. The move to Killefer was certainly popular with the players. According to the Grand Forks Herald, “Killefer called his players together in the club house and informed them of his appointment. The new pilot made an enthusiastic address which was greeted with cheers from his team mates who pledged their support to make him a success in the management of the team.”

As Bill took over the team leadership, he began to focus more on managerial responsibilities and less on playing. He continued to hit well, but his focus was on playing rookies down the stretch. The team’s standing did not improve over the final weeks, but there was confidence that Killefer could turn the team around, particularly after the Cubs finished 10-3 mark in their final 13 games. On September 12, William Veeck signed Bill to manage the Cubs for the 1922 season.

Bill Killefer played his last major league game on Saturday, October 1, a 5-3 loss at Cincinnati. He entered play late in the game and was hitless in his one at-bat. Bill hit a career-high .323 in 45 games in 1921.

Bill Killefer had no illusions about his 1922 Cubs. As the Chicago Tribune reported it, the emphasis would be on “hustlers and youngsters, speed and pep.” It also noted that the team skipper “was not given to any thoughts of winning a flag. Ball teams undergoing reconstruction do not accomplish such feats. All that Bill hopes for is a break in the luck and a berth in the first division … even if they fail they will be an interesting club simply because the development of youngsters always is an interesting process.”

The spring of 1922 marked the debut of a young catcher from Worcester, Massachusetts, named Leo Hartnett. Bill Killefer wasn’t initially impressed with the rookie and challenged him to show some intestinal fortitude. Hartnett responded and was the catcher on Opening Day.

On May 30, President Veeck and Bill Killefer buttonholed Cardinals manager Branch Rickey and dragged him into the office after the morning game of a doubleheader. The threesome then proceeded to pull off one of the most unusual trades in baseball history, swapping Max Flack to St. Louis for Cliff Heathcote, a twenty-four year old outfielder. Both men suited up for their new teams and played the second game of the twin-bill.

The 1922 Chicago Cubs finished in fifth place at 80-74, thirteen games behind the National League champion New York Giants. This mark represented a 15½-game improvement over the previous year. Bill Killefer’s first full season as manager was a remarkable success given that little was expected of a team that overachieved all season long. His emphasis on speed paid off with an increased number of stolen bases, ninety-seven (up 27 from 1921), and more patience at the plate resulted in a league-leading 525 walks. On October 27, the Cubs announced that manager Bill Killefer had been signed to a two-year contract at a substantial increase in salary.

Bill Killefer’s biggest challenge during his years as the Cubs manager was dealing with his gifted shortstop, Charley Hollocher. Bill and Charley were the backbone of the 1918 National League champions, and if a Rookie of the Year award existed then, it would have belonged to Hollocher. Plagued by a variety of mysterious illnesses, Hollocher left the 1923 Cubs camp and didn’t return until mid-May. He seemed well and followed with two and a half months of brilliant play. On July 26, his average had “slipped” to .342 and he was absent from the lineup for a couple of days. On August 3, after anticipating that he would return to the lineup, Bill Killefer came into his office and found a note: “Dear Bill, Tried to see you at the clubhouse this afternoon but guess I missed you. Feeling pretty rotten so made up my mind to go home and take a rest and forget baseball for the rest of the year. No hard feelings, just didn’t feel like playing any more. Good Luck. As ever, Holly.” Hollocher had left the team after appearing in just 66 games, leaving Killefer and the Cubs to scramble to replace him.

Killefer was never able to replace Hollocher. Hollocher returned to the Cubs in 1924 but couldn’t play at the high level he had established in earlier years. He would never play another major league game, although there were rumors for several years that he would return.

The 1923 Cubs began play in an enlarged Wrigley Field on April 17 and got off to a 7-1 start. The team then slid into .500 territory, where it remained until early July, when they steadily climbed above the break-even mark. The Cubs found their level in fourth place, where they stayed for the rest of the season, finishing at 83-71, 12½ games behind the champion New York Giants. They again led the National League in stolen bases with 181.

The Chicago Cubs got off to another good start in 1924, posting a 16-12 record by May 15, primarily because of the pitching of Pete Alexander, who won four of his first five starts. One of the highlights of Chicago’s season took place at the Polo Grounds in New York on September 20. Pete Alexander defeated the National League champion Giants, 7-3, in 12 innings to earn his 300th career victory.

With a final record of 81-72, Bill Killefer’s Cubs had posted their third straight winning season. Their fifth-place finish, however, continued their three-year trend of being out of championship competition. Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune would not point the finger of blame in Bill’s direction, saying, “No man could have done more than did the boy manager last season. He is well liked by his players and that is the big secret of managing despite what is said about ‘master minds.’”

As expected, Cubs president Bill Veeck announced in late October that Bill Killefer would return as manager for another year. A month later, Veeck announced that Oscar Dugey would not be retained as Cubs coach. This was hardly good news for Bill Killefer, who was being sent a message that there was dissatisfaction with his management.

The 1925 season started with the Cubs riddled with injuries. On May 23, they were occupying seventh place and were only a half game out of the cellar, primarily because of anemic hitting. On July 7, with the Cubs at 33-42 and in seventh place, William Veeck announced that Bill Killefer had been fired as the Chicago manager and would be replaced by Rabbit Maranville. The dismissal had been under discussion since the team’s disastrous road trip through the east in May and owner William Wrigley Jr., was known to be disappointed with the Cubs’ showing and how Killefer handled the team.

Reaction to the change was mixed. In an editorial in TSN, it was pointed out that “Killefer has had quite a long chance to try to bring Chicago into line as a possible fighting factor for the National League pennant… Killefer, or some one with him, always has had too good an opinion of the probable development of men who have been taken on, and the club has retained players who have had no possible chance to bring into Chicago that pennant which the National League would like to see again grace the shores of Lake Michigan. Killefer never had the best of discipline on the team.” Irving Vaughan of TSN commented: “Killefer simply didn’t have the material with which to make progress. The team is woefully lacking in at least two particulars and until such time as a steady pitcher and a hard-hitting outfielder is [sic] obtained there is no reason to expect the Cubs to turn the league inside out.”

With his ouster and a paycheck for the rest of the year, Bill headed for West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he and Margaret would set up their permanent off-season home.

In mid-December, the St. Louis Cardinals announced that they had hired Bill Killefer as a coach for the 1926 season. The move would reunite him with his old friend, Cardinals manager Rogers Hornsby. Killefer would serve as Hornsby’s right hand man and would be responsible for coaching the pitchers and working the baselines.

On June 22, 1926, the Chicago Cubs put Pete Alexander on waivers after he had repeated problems with drinking and breaking training rules. In St. Louis, Bill Killefer and Rogers Hornsby were talking over the possibility of claiming him. “They say Pete is through,” Killefer said. “He’s not, Rog. As long as he can stand on his feet, he’s still the pitcher I’d want out there if we were in a rough spot.” The stolid faced Hornsby nodded, “Call him and tell him we can take him,” Rog said. The Cardinals were the only team to claim Alexander, who went 9-7 in 23 games down the stretch and was a big factor in the Cardinals winning the pennant.

As the Cardinals prepared to face the Yankees in World Series Game 7 in New York, Hornsby and Killefer huddled to formulate a plan to keep Alexander sober the night before so he would be available in the bullpen. Their efforts failed, but they nevertheless used a hungover Alexander in the late going. As Peter Morris observed, “The last out was particularly symbolic. With two outs in the ninth inning of a one-run game, Ruth walked and tried to steal second. Killefer’s old protégé Bob O’Farrell caught an Alexander pitch and threw to Hornsby who tagged Ruth to end the game. With a lot of help from his old friends, Reindeer Bill Killefer was finally part of a world champion.”

The Chicago Tribune captured the crowning moment of Bill’s baseball life: “The Babe jumped to his feet and was the first to shake hands with Hornsby. Aleck made a break for the dugout to get away as quickly as possible. Two of his own mates hugged him as they ran and Bill Killefer, his pal of the old days, was seen running after him as he never had run before.”

Hornsby gave a lot of credit to Bill Killefer for the Cardinals’ championship. During spring training, Rogers told Billy Evans, “I must have much improved pitching to win and I feel sure Killefer will help me to get it.” He reflected on this statement after the Series and concluded, “Killefer did more than that… he not only improved the work of several of the erratic members of the staff but insisted that I take a chance on Alexander when the Cubs asked waivers on him.”

The glory and euphoria experienced by Killefer and Hornsby didn’t last long. Hornsby and the Cardinals could not agree on a new contract and he was traded after the season, and Killefer was offered the job on two occasions. Out of loyalty to his old friend, Bill turned down the offers, obtained his release, and signed a contract in mid-December to coach the St. Louis Browns.

Bill Killefer served as a coach for the St. Louis Browns under manager Dan Howley from 1927-1929. Killefer was Howley’s right-hand man during the season, working with the pitchers and catchers and coaching on the base paths.

The Browns finished seventh in 1927, winning only 59 games. Twelve years later, Bill mentioned them to sportswriter Jimmy Powers. “I managed and coached all sorts of duds in my day, but the all-time lulu is my St. Louis team of 1927,’ Killefer groaned. ‘The Browns?’ asked Powers. ‘No, I call them the Clowns. To show you the kind of Helpless Harries they were, the Yanks beat them 21 in a row that year and felt insulted at St. Loo’s winning the 22nd.’”

The 1928 Browns finished in third place, and the 1929 club was a notch lower in the standings. Nevertheless, Howley was at odds with the front officeowner Philip De Catesby Ball and general manager L. C. McEvoy, who liked to order changes in the lineup. Within weeks, it was obvious that Howley would not return to manage the Browns in 1930. On October 7, 1929, Bill Killefer was named the Browns’ new manager, signing a three year contract for an annual salary of $20,000.

Going in the season it was clear that Bill’s 1930 club suffered from a lack of power, with Heinie Manush as the only threat in the middle of the order. The team settled in the second division in the early going and stayed there for the rest of the way, finishing sixth. Manush was traded to Washington in early June for Goose Goslin, essentially a swap of one disgruntled holdout for another. Pitcher General Crowder was thrown in, giving owner Ball one less salary to pay.

In early August, Bill Killefer and L. C. McEvoy left the team to go on a scouting trip to Wichita Falls, Texas. They traveled in owner Phil Ball’s private aircraft, making them the first in Organized Baseball to use air travel to scout players. Sid Keener, sports editor of the St. Louis Star, interviewed Bill prior to his departure and concluded, “The Browns of 1930 are not fooling Killefer. He thought he had a first division challenger when the season opened. He has looked at them for four months and he has thrown up his hands in disgust. What are Killefer’s plans for 1931? Ralph Kress will be his third baseman. Oscar Melillo will be at second. New players will be at the other infield positions. Goose Goslin is the only outfielder who is assured of his job next Spring.”

Browns owner Phil Ball hadn’t made money on his ball club for a number of years, and the onset of the Depression forced him to cut expenses to the bone. Only 27 men were taken to spring camp in 1931, most of them young players who would receive minimal contracts. A further payroll reduction strategy was a bonus plan designed to give players an incentive to perform better by rewarding them with extra money for hits, average, and pitching wins. Bill Killefer was the first to find fault with the arrangement. In a conversation with sportswriter Al Cartwright, Bill said, “Phil Ball, the owner, had a bonus arrangement with every player on the club but I didn’t know it. I’d give the bunt sign to someone like Red Kress, and he’d look at me like I was crazy and then swing from the heels. His bonus, it seemed, paid off on so many home runs.”

Ball’s strategy didn’t produce results on the field. The Browns finished fifth, 45 games behind the Athletics. Bill Dooly, writing in TSN, remarked, “They had a skipper who made no more mistakes than the next and had a lot more wits than many…Killefer rounded out a team from a collection of minor leaguers and misfits last season. He made an organization out of a mob that in the last half of the schedule was the best Western club in the circuit. He needs very little to complete the making of a pennant contender for next season.”

Dooly’s forecast would prove to be overly optimistic. Phil Ball announced in January that he was abandoning the bonus plan and reducing salaries. The Browns went to spring training with a roster of only 26.

The 1932 Browns finished with a 63-91 record, the same as the previous year. In discussing the value of the home run, TSN’s “Fanning with Farrington” quoted Bill Killefer: “If they want to get anything like an even race in the American League, the thing to do is give us a less lively ball. Teams like the Browns simply cannot match the power clubs.”

On September 26, 1932, while driving to his home in West Chester, Bill Killefer’s car left the road and struck a concrete culvert a half mile west of Butler, Pennsylvania. Outfielder Goose Goslin, who was following behind him, pulled Killefer out of the wreck and rushed him to a nearby hospital. Killefer’s injuries were not life-threatening, but he had suffered severe facial lacerations and a broken leg. His lengthy rehabilitation was a setback to both Bill and the Browns. He had been planning to move to St. Louis to become more directly involved in player moves but the plan had to be set aside. Killefer had also missed the World Series and the chance to talk about trades with other clubs. But by December he was getting around on crutches in time for the winter meetings.

The Browns got off to a poor start in 1933 and were 4-10 and in last place after two weeks of play, scoring only 16 runs during their nine-game road trip through Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. On May 9, Phil Ball traded Rick Ferrell and Lloyd Brown to the Red Sox for Merv Shea and cash. The trade was a shock to Bill Killefer, who was not consulted about the deal. Phil Ball, whose team was playing poorly and in front of small crowds, showed that money was preferable to good players. Killefer declined to be quoted on the deal, but it was apparent that he would be in his last year of managing the Browns.

Phil Ball dismissed Manager Killefer on July 19, putting Coach Al Sothoron in charge of the last-place team. Ball felt that Bill was not getting the best out of the team, which Ball inexplicably regarded as his best club since 1922. Although newspaper headlines said he resigned, Bill told a reporter, “In a way, I’m glad it’s all over, but the report that I resigned is not exactly accurate. I did not resign.” As he told Al Cartwright, “I managed the Browns, but wouldn’t quit even that club. They had to fire me. What an outfit.”

Bill was out of Organized Baseball during 1934 and 1935. In March 1935 he was a volunteer coach for his hometown West Chester State Teachers College baseball team.

On December 12, 1935, Bill Killefer, working for Cardinals president Branch Rickey, went to Sacramento, California, to make an offer for the city’s PCL franchise to be a part of the St. Louis Cardinals’ rapidly expanding farm system, with Killefer to manage the team. The club had been repossessed by three local banks in January 1934, and new owners couldn’t be found. Killefer brokered a deal that kept the team in business and set out to find players to stock it, holding tryout camps in an effort to find young talent. Expectations were low heading into spring camp, and at one point, the PCL threatened franchise forfeiture if the club didn’t have the requisite number of players with Class A experience.

In perhaps his most effective managerial effort, Bill had the Solons at 19-26 after 45 games. As the season progressed, players came and went, and improvements in talent were offset by a lack of cohesion. The team finished in last place with a 65-111 record, 31½ games behind champion Portland.

Expectations were higher in 1937, with experienced pitching and power added to the club. The club started slowly but was in first place in May and held on to finish first at 102-76. Sacramento’s first-place finish was diminished by their flame-out in the PCL playoffs, when they lost four straight games to the San Diego Padres and their rookie left fielder, Ted Williams. In a cruel twist of fate, league rules in 1937 awarded the pennant to the playoff winner.

Bill Killefer was full of optimism heading into the 1938 season, telling the press that his team would be hard to beat. There was also the added spice of brother Red Killefer managing the Hollywood Stars, providing a couple dozen encounters between the two clubs. With the Solons hovering a few games above .500 in early May and hanging back in second or third place, the PCL had seven teams within four games of each other. Sacramento’s fortunes took a downturn on May 9 when Bill Killefer was hospitalized for problems with eating and sleeping and a weight loss of 40 pounds. He was eventually diagnosed with yellow jaundice and spent several weeks of the season in and out of the hospital.

With Sacramento in fifth place at 22-22 in mid-May, Bill left the hospital to travel with the team to Los Angeles for a week-long series with Red’s Stars. In the sixth game of the series both brothers were ejected in separate incidents. The final doubleheader of the series was on May 22, promoted as “Brotherly Love Day.” Red’s starting pitcher was tossed for protesting ball-strike calls, and Red and his players surrounded the umpire, refusing to leave the field. Seat cushions and pop bottles started to fly out of the stands, and fights were breaking out. When riot police were called to escort the umpires off the field, the game was forfeited to Sacramento. TSN ran a photo the next week with the headline, “Battling Killefer Brothers.”

By the end of July, Sacramento was out of first place and trailing the Los Angeles Angels, who dominated the Solons all year. Bill Killefer’s strong pitching staff could not overcome a weak hitting lineup, and the Angels blew away the league on the way to the pennant, which was awarded to the regular season champion that year. Sacramento finished third at 95-82, 9½ games behind the Angels.

The Solons turned the tables on Los Angeles in the playoffs by winning four games out of six. In the final series against the San Francisco Seals, the Solons won four games to one, grabbing the President’s Cup and a $5,000 bonus with a doubleheader sweep in San Francisco on October 2. At the end of his contract, Bill decided that three years away from his family was enough. “I want to remain in baseball in the East and have sent out feelers for a connection closer to home,” Bill said. By early November, it was reported that Bill had regained his normal health at his home in West Chester.

Bill accepted an offer from Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail to coach under new manager Leo Durocher in 1939. Charley Dressen was also signed to coach the club. Many pundits doubted Durocher’s ability to manage a ballclub and viewed the hiring of Killefer and Dressen as managers-in-waiting, a situation that could lead to clubhouse discord.

Bill did his usual work with pitchers and catchers during spring training at Clearwater, paying particular attention to catcher Babe Phelps, a hard-hitting catcher who was disabled twice with a broken thumb on his throwing hand the year before. Killefer drilled Phelps on keeping his meat hand closed until the pitch was in his glove. The solution worked until September 2 when Phelps again suffered a broken bone in his hand, ending his season. Once regular season hostilities got under way in mid-April, Bill spent his time coaching at first base.

Killefer traveled to Altoona, Pennsylvania, on a scouting mission on August 2 to look at shortstop Bob Ramazzotti. Bill watched the prospect play in an Altoona City League game and was impressed, signing him to a Dodger contract after the City League season ended. Ramazzotti later had a seven-year stint in the major leagues, playing 346 games with the Dodgers and Cubs.

In 1940, Bill managed the Elmira Pioneers, Brooklyn’s farm club in the Single-A Eastern League. His star player was Pete Reiser, a Cardinal farmhand freed by Commissioner Landis in his “Cedar Rapids” decision of 1938. Branch Rickey was anxious to hang on to Reiser and made an under-the-table deal with Larry MacPhail to keep Reiser for three years and then return him. Reiser had impressed Leo Durocher during spring games in 1939, and Durocher told the press that Reiser would be his starting shortstop. MacPhail responded by sending Leo a telegram telling him to stop playing Reiser. Durocher ignored the directive, so MacPhail sent Reiser to Elmira.

Reiser had another stellar spring in 1940 but was again assigned to Elmira. An angry Reiser confronted Killefer, who finally promised him that if the Dodgers hadn’t called him up by midseason, he would sell his contract to the highest bidder. When Reiser asked him how he could do that, Killefer told him, “You’re being optioned outright and I’m the general manager of this club, and I can do what I want. I don’t have more than a year or two left in this game anyway, so the hell with them. You should have been on the Dodgers in ’39.”

Reiser told author Donald Honig that he had always liked and trusted Killefer, so he accepted the promise. Sure enough, according to Reiser, Killefer came through for him. At midseason, Reiser was hitting .378, and the Cardinals sent Joe Medwick to the Dodgers for a player to be named later, who was supposed to be Reiser after the season ended and Landis’ three-year ban was over. Instead, Killefer made it clear that he would carry through on his threat to sell Reiser to the highest bidder. Larry MacPhail finally informed Branch Rickey that Reiser had attracted too much attention to keep in the minors any longer. Rickey reluctantly agreed and accepted cash instead.

The Elmira Pioneers high-water mark came on July 16 when they defeated the Springfield Nats 6-5 behind the pitching of Eddie Head. The victory allowed them to tie for first place with the Binghamton Triplets at 43-34. Their stay at the top lasted all of one day. Reiser and Head were both called up to the Dodgers, stripping Elmira of their two best players. The Pioneers went 24-38 over the next two months to finish in sixth place with a 67-72 record, twelve games behind first place Scranton.

Bill Killefer was appointed manager of the Milwaukee Brewers American Association club by President Henry Bendinger in December 1940. His signing meant that he would again be able to manage against his brother Red, the manager of the Indianapolis Indians. As always, Bill planned to build his team around youth and speed.

Bill’s Brewers opened their schedule on April 17 with a three-game set against Red’s Indians in Indianapolis. In interviews prior to the first game, Wade said, “We’re both bad losers. We usually get pretty mad at each other during a game.” According to Bill, “Friendship ceases and we’re both out to win.” Red’s club won all three games.

Things didn’t go well for the Brewers thereafter; they were at 3-9 and in last place after two weeks of play. Late May and early June weren’t kind to them either as they lost nine in a row. Sam Levy of the Milwaukee Journal, in apparent disgust at their play and berth in the cellar, tagged the team as “Bill Killefer’s Comic Strip Brewers.” The team’s poor play contributed to weak home attendance, and the financially strapped club needed help from the league in order to meet their June 1 payroll.

Finally, on June 22, it was announced that the Brewers were sold for $100,000 to a new organization headed by Bill Veeck Jr., who was treasurer of the Chicago Cubs. Killefer was dismissed as manager and was assigned to do scouting for the club for the remainder of the year, receiving his full $6,500 salary. Charlie Grimm would be the Brewers’ new manager. When Bill was reassigned, the Brewers were in last place with a 19-43 record. He was also 5-6 in games against Red’s Indianapolis club, but held a 22-14 advantage over his brother during their two PCL and American Association years.

Bill Killefer’s last on-the-field position in the major leagues was as a coach for the 1942 Philadelphia Phillies. He and Chuck Klein were hired as aides to manager Hans Lobert in December 1941. The move reunited Bill and Lobert, who were teammates on the Phillies from 1911-1914.

The Phillies were coming off a 43-111 last place finish in 1941, and manager Lobert’s goal was to bring the team up to the .500 level. “I’ll tell you a secret,” Lobert declared, “if we don’t win 50 percent of our games this year then we smell. I’ve got the makings of a good ball club.” Killefer would work with the pitchers and catchers and coach on the bases.

By Lobert’s standard, the Phillies officially smelled in 1942, again finishing in last place with an abysmal 42-109 record, 62½ games behind the World Champion St. Louis Cardinals. The Phillies didn’t win more than two back-to-back games during the season until August 23-26. This effort was so taxing that they followed it with an 13-game losing streak. The closest player to an offensive star was outfielder Danny Litwhiler, who hit .271 and drove in 56 runs.

The Phillies prepared for the 1942 minor league player draft by sending Bill all over the country to look at prospects and make a list of candidates. After the 1942 season concluded, Bill Killefer’s contract as a Phillies coach was up. Without an immediate baseball job on the horizon, Bill took a job as a railroad detective for a few months. He was then rehired by the Phillies as chief scout in May 1943. Phillies president William Cox released Bill from his position in early November and replaced him with longtime Dodger scout Ted McGrew. Killefer did not work in Organized Baseball in 1944 and 1945.

Branch Rickey brought Bill back to the Dodgers as a scout in January 1946. Killefer went to Sanford, Florida on February 1 to assist with a minor league camp for 150 players. During the summer, Bill scouted war veteran Joe Tepsic, who was signed in July by Rickey for $17,000. The Dodgers placed Tepsic on their roster for the remainder of the season. He appeared in 15 games, but batted only five times with no hits. Tepsic never made it back to the majors.

Bill Veeck became the owner of the Cleveland Indians in 1946. According to author Joseph Thomas Moore, Larry Doby’s biographer, Veeck had long intended to integrate baseball, an idea planted in his head by his father William Veeck Sr. With that in mind, Veeck hired Bill Killefer as a scout in January 1947. His plan was for Killefer to scout for black talent, a youngster who had a future in baseball. Veeck narrowed his list of prospects and told Bill Killefer and Bill Norman to focus on Larry Doby and follow his Newark Eagles team in the Negro Leagues to see how he performed. As Veeck tells it, “Killefer had worked for me in Milwaukee, and I knew him to be capable and cautious. He looked and he reported. ‘He can play in this league,’ he said. ‘I don’t know whether he belongs in the infield or outfield, but he can play.’”

Doby was purchased by the Cleveland Indians for $10,000 and signed to a one-year contract. He made his major league debut on July 5, 1947, striking out in his only at-bat in a 6-5 loss to Chicago. The first black player to play in the American League, Doby would play in the major leagues for 13 years and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1998.

Bill Killefer continued to be one of Bill Veeck’s Negro League scouts during the 1948 season. He and Harlem Globetrotters owner Abe Saperstein went to New York to see pitcher Jose Santiago of the Negro National League’s New York Cubans. Killefer and Saperstein met with Santiago in his hotel, and all he wanted to talk about was his teammate Minnie Minoso. After watching Santiago and Minoso in action, Abe and Bill recommended both to Veeck, and they were soon signed by Cleveland. Santiago pitched in 27 major league games and won over 100 games in a eleven-year minor league career. Many baseball fans and historians believe that Minnie Minoso belongs in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Bill helped scout Dick Whitman sign Camden, New Jersey, native Ray Narleski in 1947 or 1948. Narleski was a fastball pitcher who anchored the Indians’ bullpen from 1954 to 1958.

A Warner Brothers movie called The Winning Team was released in late June 1952. It depicts the story of Grover Cleveland Alexander and features Ronald Reagan as Alex, Doris Day as his wife Aimee, James Millican as Bill Killefer, and Eve Miller as Margaret. Orval Hopkins of the Washington Post thought the film was a “familiar baseball-and-kisses routine” and called the casting of Reagan as Alexander a “thundering error.”

Bill Killefer’s wife Margaret died at age 65 on March 11, 1954. Bill would remain in Marshallton, their home since 1945, for another year before moving in with his daughter Margaret Ann in the northern suburbs of Wilmington, Delaware.

As he entered his 60’s, Bill Killefer began to suffer from a variety of ailments. In 1949, it was arthritis. He spent considerable time over the next few years traveling to Paw Paw to visit Ola and bathe in the mineral springs there. In July 1958, Bill was hospitalized as a diabetic patient at the Veteran’s Administration Hospital in Elsmere, Delaware. He returned to the hospital in September 1959 for surgery after a mild heart attack.

Bill Killefer made many friends no matter where he went. His adopted hometown of West Chester was no exception. Ed D’tore of the Daily Local News knew him “as a great hand at telling a story of his playing days in the big leagues.”

Apparently Bill didn’t care to share many of his stories with writers. Al Cartwright of the Wilmington Journal-Every Evening knew Killefer for five years and said he “had a tough time getting Bill to reminisce… he would rather talk about the golfing prowess of neighbor Roy Marquette or harness racing.”

Cartwright was Bill’s driver on several occasions and noted that, “it was our pleasure to chauffeur him around and his dry wit on those shopping trips would fracture us.” Their routine would usually take them to Bill’s old haunts in the West Chester area. First, however, they would stop at a produce stand on Rt. 202, “where he’d jab jokes at the proprietor, whom he introduced as an old boxer–’you could write a good story about this man.’” Then they would head out into the country to Bill’s favorite sausage mill “for a few more light insults.” Then there was haggling over the price of apples at a fruit stand, followed by a stop at a barber shop in West Chester to see some cronies, followed by a visit to his sister-in-law. “One time the itinerary included a visit to Herb Pennock’s widow in Kennett Square,” Cartwright said, “and we were always going to hop over to New Jersey to see Goose Goslin, but that one never developed.”

Cartwright’s last outing with Bill was a trip to Philadelphia on April 16, 1960. Bill enjoyed the greeting he received from all the old-timers at Connie Mack Stadium, but he wouldn’t accompany Cartwright to the Phils’ dugout to meet new manager Gene Mauch. “Those guys don’t want to meet me,” Killefer insisted. Instead he took off to buy some cigars for the Phillies’ equipment manager. “Later, when we rejoined Killefer in the press box, he revealed that he had wandered over to the Braves’ visiting chambers to say hello to Chuck Dressen. Quietly, unobtrusively, Bill always caught up with his friends. If we had it our way, there would have been a brass section preceding him.”

On July 3, 1960, Bill Killefer was dead at age 72. He had been taken to the Veterans Administration Hospital in Elsmere, Delaware, on June 30, and his condition suddenly became critical. Death was attributed to hemorrhaging in the digestive tract. He was survived by his son William, his daughters Jane and Margaret Ann, and his sister Ola. His body was transported to Paw Paw, Michigan, where services were held on July 7 at the Hawley Funeral Home. He is buried at Prospect Hill Cemetery in Paw Paw.

Afterword

It was my good fortune and privilege to know Bill Killefer over the last few months of his life in 1959-1960. We were neighbors; he lived on Prospect Drive in Blue Rock Manor and I lived a block away on Woodrow Avenue. A junior at Brandywine High School, I was a seldom-used relief pitcher on the varsity baseball team and a part-time “soda jerk” at the Tigue’s Pharmacy lunch counter.

Bill Killefer made it a point to take an evening stroll from his house to Tigue’s, sometimes to pick up a prescription, always to sit at the lunch counter and shoot the breeze about baseball. Bill was portly, stooped over, and his fingers were thick and gnarled, with two or three slightly askew at the knuckles. He had a ready smile and was shy and quiet in a good-natured way with a healthy dose of dry wit sprinkled in. Bill always engaged in playful banter with anyone who cared to play along. At the drug store, you could count on him mixing it up with the staff, with everyone laughing and smiling at the end.

Bill and I talked a lot about the Phillies. His comments were almost always prefaced with “same old Phillies.” He also gave me baseball advice, telling me to pay attention to conditioning my legs and practicing as if I was playing in a game. We sometimes talked about harness racing, and he would give me tips on how to place bets. Brandywine Raceway was three miles north on Rt. 202 and Bill would take in a night of racing on occasion. According to Al Cartwright, Bill “never failed to put a bob on the ‘baseball horses’ owned by Charley Keller and Vic Keen.”

I vividly recall Bill telling me about barnstorming through Cuba in 1911. One of the items he mentioned was the quality of the cigars. He was also impressed by the players, particularly pitcher Jose Mendez, who beat the Phils twice and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006.

I took Bill’s baseball advice to heart, but had few positive results. My coach used me to hurl batting practice, and I appeared in only three games, pitching 4 1/3 innings with an ERA of 8.92. Bill would listen to my stories, remaining upbeat for my benefit, always offering encouragement and telling me that I could improve.

It wasn’t long after my baseball season was over in June that I got a phone call from Bill, who needed a ride to the Elsmere Veteran’s Administration Hospital, where he would be admitted for some tests the next day. I walked over to his house, and we hopped in Margaret’s Chevy for the 15 minute drive. But first, there was a stop at the store for Bill’s favorite smokes, a carton of Marlboros. I dropped him off at the hospital, and he told me he’d see me in three or four days at Tigue’s. Sure enough, there he was a few days later, and we were back to talking about the Phillies, who got off to a horrible 12-27 start under Gene Mauch. “It will get worse before it gets better,” Bill said.

On June 30, 1960, I got another phone call from Bill asking for a ride to the VA Hospital. Bill complained of leg pains, but we nonetheless had to make a stop for his smokes. He said little during the ride. When we arrived at the hospital, I helped him up the steps, sat with him during his admission process, and accompanied him to his room, where we said good-bye. He died three days later from hemorrhaging in the digestive tract. I found out about it three days after his death when I saw his obituary in the paper.

I was stunned when Bill passed on and reacted by starting a clipping file, which grew over the years. I would always think of him every baseball season, and had a notion that I would learn more about him someday. Now, 48 years later, I am semi-retired and doing just that. As I’ve researched and come across his quotes, I can hear his voice, plain as day, as if he was sitting across the lunch counter from me.

Bill was right when he told me that I still had time to grow, learn, and enjoy baseball. My hardball career ended after my 1960 high school season. When I was in college two years later, I discovered slow-pitch softball, a sport I’ve now played continuously for 41 years. I enjoy viewing myself as Reindeer Bill’s last coaching project, albeit at a much lower level. I still think about Bill’s advice, carry his calm but “never-say-die” attitude into games, and sometimes feel like he is sitting on my shoulder giving me encouragement.

Sources

Ahrens, Art. “Hack Miller, Cub Strongman.” The National Pastime (1990): 54-56.

Ahrens, Art. “Tragic Saga of Charlie Hollocher.” Baseball Research Journal (1986): 6-8.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. Ninth Edition. New York: Macmillan, 1993.

Cataneo, David. Peanuts and Crackerjack: A Treasury of Baseball Legends and Lore. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1991. 54.

Creamer, Robert. Babe: The Legend Comes to Life. New York: Fireside, 1974. 315.

Di Salvatore, Bryan. A Clever Base-Ballist, the Life and Times of John Montgomery Ward. New York: Pantheon Books, 1999.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Beisbol Cubano: Las Grandes Ligas 1878-1961. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2005.

_____. Cuban Baseball, a Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2003.

Gillette, Gary, and Pete Palmer, eds. The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. Fourth Edition. New York: Sterling, 2007.

Golenbock, Peter. The Spirit of St. Louis: a History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns. New York: Avon, 2000.

_____. Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs. New York: St. Martins, 1996.

Hamann, Rex, and Bob Koehler. American Association Milwaukee Brewers. Charleston, SC: Arcadia P, 2004. 101.

Honig, Donald. Baseball When the Grass Was Real. Lincoln: University of Nebraska P, 1975. 290-315.

Hunsinger, Louis, and James P. Quigel. Williamsport, PA. Baseball. Charleston, SC: Arcadia P, 1998. 111.

Jacobs, Martin, and Jack McGuire. San Francisco Seals (Images of Baseball). San Francisco: Arcadia P, 2005. 10.

Jacobson, Sidney. Pete Reiser: the Rough-and-Tumble Career of the Perfect Ballplayer. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2004.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free P, a Division of Simon and Schuster, Inc., 2001. 631.

Jordan, David M. Occasional Glory: a History of the Philadelphia Phillies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2002.

Kavanagh, Jack. Ol’ Pete: The Grover Cleveland Alexander Story. South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1996.

McNeil, William F. Backstop: a History of the Catcher. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2006.

Moore, Joseph T. Pride Against Prejudice: a Biography of Larry Doby. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1988. 38-40.

Orodenker, Richard, ed. The Phillies Reader. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996.

Simon, Tom, ed. Deadball Stars of the National League. Washington, DC: Brassey, Inc., 2004. 215-216.

Snyder, John. Cubs Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day with the Chicago Cubs Since 1876. Cincinnati: Emma Books, 2005. 199-201.

Spatz, Lyle, ed. The SABR Baseball List and Record Book. New York: Scribner, 2007.

Thorn, John, and John Holway. The Pitcher. 1st ed. New York: Prentice Hall P, 1987.

Vitti, Jim. The Cubs on Catalina: a Scrapbook of Memories About a 30- Year Love Affair Between One of Baseball’s Classic Teams and California’s Most Fanciful Isle. Catalina Island, CA: Settefrati P, 2003. 22-105.

Westcott, Rich. Phillies Essential: Everything You Need to Know to Be a Real Fan. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006. 28-33.

Zingg, Paul J., and Mark Medieros. Runs, Hits and an Era: the Pacific Coast League 1903-1958. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois P, 1994.