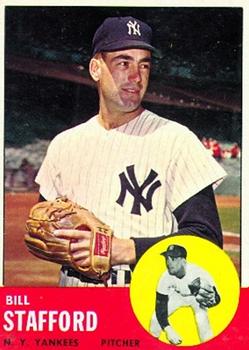

Bill Stafford

“You automatically go all out, regardless of pain or what.”1 This was the guiding principle of New York Yankees pitcher Bill Stafford’s baseball career. Never had his philosophy been more tested than on the afternoon of October 7, 1962. After a screaming liner off the bat of San Francisco Giants outfielder Felipe Alou smashed into Stafford’s shin in the top of the eighth inning, the right-hander instinctively grabbed the ball and flung it to first, throwing the runner out. Only then did he react to the searing pain. Stafford, however, did not leave the field. Despite his injury the New York hurler finished the contest, leading his team to a 3-2 victory over San Francisco in Game Three of the 1962 World Series. It was a gutsy performance borne out of Stafford’s blue-collar background, and proved to be his magnum opus on the mound.

“You automatically go all out, regardless of pain or what.”1 This was the guiding principle of New York Yankees pitcher Bill Stafford’s baseball career. Never had his philosophy been more tested than on the afternoon of October 7, 1962. After a screaming liner off the bat of San Francisco Giants outfielder Felipe Alou smashed into Stafford’s shin in the top of the eighth inning, the right-hander instinctively grabbed the ball and flung it to first, throwing the runner out. Only then did he react to the searing pain. Stafford, however, did not leave the field. Despite his injury the New York hurler finished the contest, leading his team to a 3-2 victory over San Francisco in Game Three of the 1962 World Series. It was a gutsy performance borne out of Stafford’s blue-collar background, and proved to be his magnum opus on the mound.

William Charles Stafford was born on August 13, 1938, in the small Upstate New York town of Catskill, on the west bank of the Hudson River about 120 miles north of Manhattan.2 The only child of William L. Stafford, a brickyard worker, and his wife, Jane, Bill grew up a few miles north of Catskill in the village of Athens. His father, a onetime semipro pitcher, encouraged Bill’s pursuit of athletics. When Bill was in middle school, William the elder painted a target on canvas and set it up in the family’s backyard. Bill would spend his summers firing baseballs from a regulation mound at the bull’s-eye, building his arm strength and perfecting his control.

At Coxsackie-Athens High School, Stafford was a two-sport star. On the basketball court he became the first player in the school’s history to score 1,000 points.3 On the baseball diamond, his statistics were even more impressive. He batted over .400 in all but his freshman season. During his initial year on Coach Doug Erickson’s squad, Bill, then a shortstop, added pitching to his résumé. “I needed a relief pitcher so I thought I’d try Stafford,” said Erickson. “This is where it all started – he struck out all 15 men he faced.”4 In his first start, the young twirler K’d an astounding 31 batters in a 17-inning, 2-1 Coxsackie-Athens triumph over rival Ravena. He finished his varsity career with a 19-2 record, which included two no-hitters his senior season. Spurning basketball scholarship offers to Duke, Syracuse, and Holy Cross, Stafford opted instead for baseball.5 On the day he graduated from high school in June 1957, there were 15 big-league scouts in Athens making their sales pitches in the Stafford home. Ultimately, Bill signed on June 28 with Tom Kane and Harry Hesse of the New York Yankees for $4,000.6

The teenager was shipped south to St. Petersburg of the Class D Florida State League. He went 5-3 in nine starts for the Saints, but posted a stellar 0.88 earned-run average.7 His promotion to Class A Binghamton for the 1958 season was therefore no surprise, but Triplets manager Steve Souckock’s decision to start the Hudson Valley native in the team’s season opener was indeed unexpected. Stafford would live up to his top-prospect billing, leading the club in wins with 11 and topping the Eastern League with a 2.25 ERA.8 On the strength of his performance, Bill was asked back to St. Petersburg the following February – but this time as a spring-training invitee of the Yankees.

Despite his achievements, Stafford’s tenure with the Triplets was also marred by the first in a series of serious injuries that bedeviled the pitcher throughout his professional career. A fall down a flight of stairs in Binghamton led to chronic back issues. Lingering lumbar problems help explain the young hurler’s regression in 1959, when he played for the Richmond Virginians of the International League. Stafford’s statistics – including his 1-8 record and 6.17 ERA –justified his late-season demotion back to Binghamton. Stafford undoubtedly fared better off than on the field that year: In October, he married Janice Maher, his high-school sweetheart and the eventual mother of his first two children, Billy and Susan.

Stafford rebounded in 1960 with a dominating season in Richmond. He tossed 58 more innings and allowed 26 fewer runs than he did in his previous stint with the V’s. He was, upon his late-summer call-up to the majors, among the International League leaders in wins, shutouts, and ERA. When several Yankee scouts recommended that Stafford was ready for the Bronx, club brass listened.9

Stafford was a fresh-faced 22-year-old when he made his American League debut on August 17, 1960. The 6-foot-1, 185-pound righty featured four pitches: fastball, curveball, changeup, and slider. His fastball, when effective, had a devastating sink to it.10 “Stafford had this really nasty heavy sinker that he threw. He ate hitters up with it,” said Johnny Blanchard, the Yanks’ backup backstop.11 That summer Blanchard and his New York teammates were battling Chicago and Baltimore in a three-team AL pennant race. The Yankee offense, led by Mickey Mantle and MVP-to-be Roger Maris, had been carrying the squad, as manager Casey Stengel’s pitching staff was inconsistent at best. Throughout the season, the Old Perfessor used starters as relievers and vice versa, hoping to find the right elixir to cure his team’s pitching ills. Thus, when Stafford was brought up from Richmond on August 15, Stengel started him two days later in an effort to jumpstart the team. Debuting at Fenway Park against Ted Williams and the Red Sox, Stafford held Boston to two runs and eight hits in 6? innings. New York would go 7-1 in Stafford’s starts, and Bill won some key games for the Yankees down the stretch, including a six-hit, complete-game triumph at Detroit on September 9, that cut the Orioles’ league lead to a half-game. The two clubs were tied as late as September 15, when the Bombers ripped off a year-ending 15-game winning streak, leaving the O’s and White Sox in the dust.

Awaiting the 97-win Yankees in the 1960 World Series were the National League’s 95-win Pittsburgh Pirates. Stengel’s mismanagement of the pitching staff during this fall classic was a major factor in the legendary manager’s termination after the season. Following Art Ditmar’s disastrous start in Game One, Casey seriously considered starting Stafford for Game Five. Instead, he changed his mind and went with Ditmar, who was battered by the Bucs for three runs in an inning and a third. In relief, Stafford threw five scoreless frames, leading critics to question why the septuagenarian Stengel had started the veteran and not the rookie sensation. In Game Seven the Yankee manager once again was going to pitch Stafford. The night before the game, he informed Bill that he would be the starter.12 Stengel, though, pulled another switch and decided to pitch Bob Turley, who had won the second contest of the Series. However, Turley struggled and was replaced by Stafford in the second inning, but neither Bill nor the other three Yankee relievers used by Stengel that day in Pittsburgh were effective. The Yanks’ season would end in agony on a Ralph Terry hanging slider to Bill Mazeroski.

Shortly after the Series, Stafford entered the US Army under its six-month program. Discharged in March 1961, he missed six weeks of spring training. When he arrived at the Yankees’ camp in St. Petersburg, Bill was not in playing condition, and he struggled throughout the preseason. He also suffered from a sore shoulder. “It takes about a month to get in shape,” said Stafford. “I only had two weeks before the season began.”13 Beginning the year in the bullpen, Stafford found his way into new manager Ralph Houk’s rotation by June. The hurler rewarded the Yanks with a trio of complete-game victories in his first three regularly scheduled starts. In July Stafford recovered from another shoulder injury by twirling two shutouts.

The Yankees were in full swing, too, rattling off a record of 42-18 for July and August. The team had solved its early-season pitching problems, as Stafford and Rollie Sheldon became the young guns in a Pinstripe staff anchored by Whitey Ford and Ralph Terry and a bullpen dominated by Luis Arroyo. The Bronx was abuzz in the summer of ’61 with both the pennant race with the Tigers and with Mantle and Maris’s chase of Babe Ruth’s home-run record. Stafford won 14 contests that season, but his last victory was the most memorable of all. On Sunday, October 1, with the Yankees having already wrapped up their 26th American League title, all eyes turned to Maris, who was stuck on 60 homers, just one short of breaking the Bambino’s iconic mark. In the bottom of the fourth inning of his club’s final game, Maris deposited a Tracy Stallard pitch into the right-field seats, setting the record. “I don’t think I ever pitched a harder game in my life. … Everyone was pulling for Roger that day,” said Stafford, the winning pitcher in New York’s 1-0 victory over Boston. “That’s just the kind of team we were, one that pulled for each other all the time.”14

Stafford finished his sophomore season with a 14-9 record, including three shutouts, and a sparkling 2.68 ERA, good for second place in the AL. In the World Series against Cincinnati, Houk handed the ball to Stafford in Game Three, and the budding star came through for his manager. Although Bill exited the game trailing by a run, he pitched effectively, yielding two runs on seven hits in 6? innings while striking out five Reds. The 109-win Bombers, meanwhile, used solo homers by Blanchard and Maris in the final two innings to steal the game and capture momentum in the Series, which they won in five games. Stafford’s contributions to the Yankees’ triumph did not go unnoticed by his skipper. “I want to give special tribute to pitchers Luis Arroyo and Billy Stafford,” said Houk. “I don’t think that we could have done it without them.”15

In 1962 New York returned its top three starters from the previous year: Ford, Terry, and Stafford. The upstate New York native had cemented himself into the number 3 slot in the rotation. Stafford certainly had reason for optimism: This season, he had no obligations to Uncle Sam; he would be with the Yanks the entire spring. Meanwhile, he was gaining repute in the New York media for being highly confident – arrogant, almost. This reputation was nothing new for Stafford. “Cocky? He even walked cocky,” recalled Coach Doug Erickson, commenting on the pitcher from his high-school days. “When you are that good, people don’t like you.”16 The Yankees beat writers took notice of the self-assured way Stafford strolled to the mound, which they described in great detail. “Bill had a lumbar curve and when he walked some could have judged it as being ‘cocky.’ As a teammate you knew differently,” said Sheldon.17

Stafford pitched poorly in April, but returned to form thereafter, winning four of his next five decisions, including a two-hit blanking of the Cleveland Indians at Yankee Stadium on June 7. The Yankees were, as expected, in contention once again for the pennant in the summer and fall of 1962. By the end of August, however, the Bronx Bombers’ once-comfortable lead over the upstart Minnesota Twins had shrunk to two games. A September surge by the Yanks helped extend the lead to four games, but the team lost the first two contests in a late-September series in Chicago. With the pennant almost within reach, it was Stafford’s responsibility to stop the team’s slump. On September 23, more than 30,000 fans watched as he outdueled Early Wynn of the White Sox in a ten-inning contest in which both pitchers went the distance. The Yankees clinched the pennant two days later.18

The Yankees’ opponent in the 1962 World Series was the San Francisco Giants, who had just won a dramatic three-game playoff with New York’s other former National League team, the Los Angeles Dodgers. After splitting the first two games at Candlestick Park, the Series moved to the Bronx, where Stafford squared off against the Giants’ Billy Pierce. Although he labored through a 24-pitch first inning, the Yankee starter settled down nicely. Provided by his teammates with a 3-0 lead, Stafford returned to the mound in the top of the eighth. After giving up a leadoff single to José Pagán, Stafford induced pinch-hitter Matty Alou to ground into a fielder’s choice. The next batter up was Matty’s older brother, Felipe. The elder Alou rocketed a ball right up the middle, and squarely into Stafford’s shin. “Suddenly I got woozy,” said the pitcher, who despite the intense pain recorded the out.19 Yankees trainer Joe Soares sprayed Stafford’s injured leg with ethyl chloride and provided him with smelling salts. After seeing a few warm-up pitches, Houk decided to leave his hurler in the game. It was a bold move by the Major which ultimately paid dividends. Stafford escaped the eighth, getting second baseman Chuck Hiller to ground out to second. Although he gave up a two-run homer in the ninth, Stafford was allowed to finish what he started, as he retired Jim Davenport to end the game. The Yankees’ Number 22 had given his squad a two-games-to-one Series lead. His skipper was impressed. “Usually when a pitcher gets hit like that, he starts pitching up high because he won’t put weight down on that bad leg,” said Houk. “Stafford put more weight down on it after he was hurt. He really fired.”20

When he woke up the next morning, Stafford’s shin and knee were badly bruised and swollen. With a chance to close out San Francisco in Game Six, Houk decided to go with Whitey Ford on short rest instead of a gimpy Stafford. This Series, however, was destined to go seven games. The Yankees came out on top in an epic Game Seven. When second baseman Bobby Richardson secured Willie McCovey’s liner, Ralph Terry’s 1-0 masterpiece was preserved. It was not the bats of 1962 MVP Mickey Mantle and the hitters that had won the fall classic; it was the pitching of the Yanks’ “Big Three.”

Stafford began the 1963 season with a new home address – in Yonkers – and with great confidence. The press had even taken to calling him the “Cool Cookie from the Catskills” following his World Series heroics.21 On April 10 the weather in Kansas City was cooler than cool – frigid, in fact – when Stafford made his first start of the year. “The temperature was about 20 and I was wearing an electric jacket while I was on the bench,” he remembered.22 Stafford was shutting out the Athletics’s 3-0 when, with two outs in the bottom of the seventh inning, he threw a fateful 1-and-2 fastball to Billy Bryan. He felt a sharp pain in his right shoulder and heard a frightening sound. “It was like a twig snapping,” he said.23 The injury, according to the Yankees’ team physician, Dr. Sydney Gaynor, did not appear to be serious. Doctors at the time “didn’t know the difference between a rotator cuff and a Dixie Cup,” declared Stafford.24 He was never the same pitcher that season, or for that matter for the rest of his career. Through July 14, he had a 3-6 record with a dismal 5.75 ERA in 16 appearances, 13 of which were starts. In his first game after being removed from the rotation, Stafford hit a batter with a pitch and doled out free passes to three more. When reporters questioned him after the game about issuing the walk-off walk, an angered Stafford threatened to punch one of them in the face.25

More frustrations were to follow. In addition to pitching with an undiagnosed rotator-cuff injury, Stafford hurt his groin sliding into a base and was afflicted by a mysterious body rash that season.26 His irregular pitching schedule and periods of inactivity contributed to his overeating, as he ballooned to 215 pounds. Stafford’s final stat line for the year included a 4-8 record, a 6.02 ERA and an especially abysmal 1.628 WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched). The Yankees again won the pennant in 1963. Stafford, however, was not utilized in the team’s four-game World Series sweep at the hands of the Dodgers.

Looking to bounce back in 1964, Stafford came to spring training 29 pounds lighter. His plan was to regain his place on the Yanks’ starting staff. However, the emergence of young twirlers Jim Bouton and Al Downing meant that Bill would be consigned to the bullpen for the season. On paper his numbers looked good: a 5-0 record, 2.67 ERA and 5.83 strikeouts per nine innings. Yet stamina issues and tendinitis limited Stafford to 60? innings pitched. The New York Times declared him to be “one of the most unsuccessful undefeated pitchers in history.”27 For the fifth time in his five big-league seasons, Bill was part of a pennant-winning Yankee team. But for the second consecutive year, New York lost the fall classic, this time to the Cardinals. It was also the second straight year that Stafford did not pitch in the postseason. Once again in 1965, Stafford took aim at a spot in the Bombers’ rotation. The season was, however, not a good one, neither for Stafford nor the Yankees. Although the right-hander secured a starting role, he was available only on a part-time basis. Flare-ups of tendinitis in his pitching shoulder kept Stafford out of action for parts of May and September and landed him on the disabled list for the entire month of July. He finished the year 3-8 for a sixth-place New York team. The Yankee dynasty was over. So too was Stafford’s career in the Bronx.

Stafford was in camp with the Yanks to start the 1966 season, but was optioned to the club’s Triple-A affiliate in Toledo. He was called up on June 9, but was instead immediately traded to the Athletics. Stafford, pitcher Gil Blanco, and outfielder Roger Repoz were sent to Kansas City in exchange for pitcher Fred Talbot and catcher Billy Bryan. The A’s put Stafford in their rotation, with unsatisfactory results. He was sent down to the Birmingham Barons of the Southern League. In 1967, after spending most of the season with the Double-A Barons, Stafford was brought back to Kansas City at the end of July. He was used in a limited role out of the bullpen, and pitched in his final major-league game on September 19, against the Twins. “I was just hanging around,” said Stafford of his time with the A’s. “When your shoulder hurts, you can’t do anything.”28 In his final two seasons in Organized Baseball, he bounced around the Pacific Coast League, moving from Seattle to Phoenix to Tucson. His last attempt to resurrect his major-league career came in 1969, when he attended spring training with the Seattle Pilots, but he was released just before the season began.

After retiring from the game, Stafford gained employment in various sales and promotions jobs, working for companies including the Waterman-Bic Pen Corporation, Grolier Enterprises, and the Shechter Association.29 At one point he owned a country bar in Michigan called JR’s Place.30 His love of sport, however, never subsided. Even before he retired as a player, he became a coach, serving for two years as an assistant pitching coach at Southern Connecticut State College in New Haven. “I really enjoy the coaching of clinics and would probably consider going into coaching full time with a major college team if the opportunity ever came up,” Stafford told a reporter.31 He went on to coach high-school baseball, in addition to serving as an instructor in numerous youth and fantasy camps.

As an athlete, Stafford’s prowess was not limited to baseball and basketball. He was a great bowler and pool player, and was especially proficient in golf. He shot a one-under-par 69 at the 1965 Montauk-Gurney’s Inn Invitational Amateur Championship, a performance that led golf pro Harry Obitz to promise his support if Stafford ever wanted to join the PGA tour.32 “We played a lot of golf together,” said Ralph Terry, a terrific golfer himself. “He was an excellent player.”33 The day before Game Three of the 1962 World Series, Bill was nervous about his coming start and asked Rollie Sheldon to go golfing with him. “It started to rain, but we played on,” recalled Sheldon. Rollie was unprepared for this impromptu day on the greens, so he did not have a chance to change out of his new alligator shoes, which were ruined in the rainfall. “But it was worth it to help Bill relax,” he said.34 The 1960s Yankees were on the links frequently, both on off days and in the offseason. In addition to Terry and Sheldon, Stafford often golfed with teammates Mickey Mantle, Jack Reed, and Hector Lopez.35

Life after the major leagues brought changes to Stafford’s family life. After a divorce from Janice, Bill remarried, tying the knot with Sharon Beedell in October 1972.36 They settled down in Canton, Michigan, where they raised two children, Kimberly and Michael. Mike carried on his father’s baseball legacy, pitching at Ohio State University before being selected in the 1998 June Amateur Draft by the Toronto Blue Jays. The younger Stafford, a lefty reliever, played four minor-league seasons in the Blue Jays, Yankees, and Milwaukee Brewers organizations before finding his true calling in the game: coaching. Returning to his alma mater in 2011 as an assistant coach, Mike credited his father with teaching him the art of pitching: “Dad always told me the most important thing was to know that you were better than the guy in the batter’s box.”37

Just eight days after the shocking national tragedy of 9/11, the Stafford family endured an unexpected personal tragedy when Bill suffered a heart attack and died in his Canton home. He was 63 years old. Although his life came to a premature end, Stafford’s Yankee legacy will live on. He will forever be remembered by fans in the Bronx for his heroics in the 1962 World Series and his role in Maris’s 61st-home-run game. Though injuries cut his career short, Stafford compiled a respectable 43-40 record and a 3.52 ERA in eight big-league seasons. A member of five pennant and two World Series winners, Bill Stafford gave the game everything he had. “My father always told me to do the best you can,” Bill said. “That’s what I live by.”38

Notes

1 New York Times, May 4, 1962.

2 There is some confusion as to whether Stafford was born in 1938 or 1939. His player file in the Giamatti Library at the National Baseball Hall of Fame records 1938 as his birth year, while Baseball-Reference.com states that Stafford was born in 1939. Of further interest, his 1961 Topps baseball card goes with 1939, but 1938 is printed on all of his subsequent Topps cards. The Social Security Death Index, accessed through Ancestry.com, records that Stafford was born on August 13, 1938, and died on September 19, 2001 at age 63. This data is undoubtedly accurate.

3 Knickerbocker News (Albany, New York), January 26, 1957; Schenectady Gazette, August 26, 1960.

4 Schenectady (New York) Gazette, August 26, 1960.

5 Schenectady Gazette, August 26, 1960; Stafford Hall of Fame file.

6 Stafford Hall of Fame File; Times Union (Albany), June 14, 1988. Years later, Stafford lamented the fact that Major League Baseball’s $4,000 signing bonus limit was eliminated that September. He estimated that this cost him between $150,000 and $250,000.

7 All minor- and major-league statistics were obtained from baseball-reference.com.

8 Stafford was the Eastern League ERA leader in 1958 for pitchers who started more than ten games.

9 Knickerbocker News, August 17, 1960.

10 Newsday (Long Island, New York), March 14, 1962.

11 Quoted in Sonny Fulks, “Mike Stafford’s (Very) Special Baseball Story,” Press Pros Magazine, April 24, 2013, pressprosmagazine.com/mike-staffords-very-special-baseball-story/.

12 William J. Ryczek, The Yankees in the Early 1960s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 38.

13 Newsday, March 14, 1962.

14 Quoted in Randy Schultz, “Bill Stafford and Hector Lopez: Where Are They Now…?,” Baseball Digest, June 1991, 68.

15 Quoted in Ryczek, 68.

16 Times Union, June 14, 1988.

17 Rollie Sheldon, letter to the author, July 23, 2013.

18 Bill Morales, New York Versus New York, 1962: The Birth of the Yankees-Mets Rivalry (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012), 169.

19 Herald Statesman (Yonkers, New York), October 8, 1962.

20 Newsday, October 8, 1962.

21 Binghamton (New York) Press, July 18, 1963.

22 Times Union, June 14, 1988.

23 Times Union, June 14, 1988.

24 Times Union, June 14, 1988.

25 Newsday, July 16, 1963.

26 Ryczek, 137.

27 Quoted in Ryczek, 202.

28 Times Union, June 14, 1988.

29 Stafford Hall of Fame File; Schultz, 67.

30 Mike Stafford, email to the author, August 7, 2013.

31 Times Record (Troy, New York), July 14, 1973.

32 Stafford Hall of Fame File.

33 Ralph Terry, letter to the author, July 13, 2013.

34 Rollie Sheldon, letter to the author.

35 Thomas Van Hyning, “Jack Reed,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/13225d55; Hector Lopez, letter to the author, July 23, 2013.

36 Mike Stafford, email to the author.

37 Quoted in Fulks.

38 Newsday, July 11, 1964.

Full Name

William Charles Stafford

Born

August 13, 1938 at Catskill, NY (USA)

Died

September 19, 2001 at Wayne, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.