Billy Colgan

Catcher Billy Colgan appeared in 48 big-league games in the summer of 1884 for the Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the American Association before moving to the Pacific Northwest. Later, after his tragic death, he became the first former major leaguer buried in the state of Montana.

Catcher Billy Colgan appeared in 48 big-league games in the summer of 1884 for the Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the American Association before moving to the Pacific Northwest. Later, after his tragic death, he became the first former major leaguer buried in the state of Montana.

According to baseball historian Jim Price, William H. Colgan was born during the Civil War, in East St. Louis, Illinois, on March 19, 1862. While his career numbers are listed under “Ed Colgan” in Total Baseball, as well as in online statistical databases, I never encountered this in the newspaper accounts of his playing days, but rather much more endearing nicknames such as Billy, Little Willie, and even Shorty. His mother, Louise Colgan, was a 54-year-old widow in 1880, the daughter of a Canadian father. She could neither read nor write and was “keeping house” with Billy, age 19, the only child still at home. While a “sister living in St. Louis” is mentioned in Billy’s obituary, she is missing from this household roll call.

Colgan got his start in the professional ranks as a catcher with Springfield (Illinois) of the 1883 Northwestern League. His first pitch handled behind the dish was most likely delivered by Florence P. “Fleury” Sullivan, a fellow East St. Louisan whom Colgan would catch again in his major-league debut the following year.

Billy Colgan and Fleury Sullivan may have been childhood friends. Sullivan remains the pitcher with the highest career strikeout total (189) with just one season of major-league service. Sullivan was murdered in Scully’s Saloon by bailiff James J. Enright of the East St. Louis city court during a political argument in 1897. His obituary in Sporting Life said, “Sullivan organized the East St. Louis Nationals in 1889 with associates the Millard Brothers [Frank and Ed], Colgan and other amateur cranks.” It also mentioned that Colgan played professionally at Spokane, Washington, in 1890, while Sullivan joined a local newspaper team as a catcher. The obituary concluded, “Sullivan was always a great favorite with the players and patrons of the game on account of his good nature and pleasant ways.”1

Colgan was listed alongside Sullivan and many other Springfield ballplayers in December of 1883 as signed with the “Chicago Union League Club, regarded as a very strong team.”2 He would instead catch on with Pittsburgh of the American Association, making his debut on May 3, 1884. Colgan made two safe hits that Saturday off Athletics pitcher Al Atkinson, while Sullivan won his first big-league game, 9-8. It was the Alleghenys’ first win but they would win only 29 more. (It was a 108-game season.) Colgan caught in only 48 games (and played four games in the outfield), more than anyone else caught for the Alleghenys, and good for sixth overall on a squad that saw 34 players take the field for a team that finished in 11th place, 45½ games behind the New York Metropolitans (who suited up a total of 16 men). Colgan most likely squatted in the same catcher’s position as Moses Fleetwood Walker, playing together in the same leagues in 1883-84. Colgan played his last big-league game on the final day of the season, a 9-4 loss to the Louisville Colonels.

At the outset of the 1885 season, Colgan joined Kansas City of the Western League, suiting up for manager Ted Sullivan. After the team suffered four humiliating defeats in a single week in late May, many of the local bugs criticized the manager for not going after another pitcher, as Peek-A-Boo Veach couldn’t handle the entire load. By June 17, Sporting Life reported that the Western League “was on a ragged edge”3 with disbandment on the horizon after Omaha, Cleveland, and Toledo dropped out of the six-team league, leaving only Indianapolis, Kansas City, and Milwaukee. The remaining teams appealed to the Southern League for absorption.

By July 8, Colgan had joined three other St. Louisans playing with the Memphis Reds as Ted Sullivan took over the reins of the sub-.500 Southern League team. From his first game, Colgan’s “splendid play behind the bats” was lauded by the Memphis Daily Appeal as more than a thousand fans saw his pitcher allow only two men to reach third base in a shutout of Birmingham. In a game in late July, with runners on first and second, Colgan made a heady play from his catcher position, intentionally dropping a third strike, then forcing a baserunner at third, with a double play turned on the relay to first to get the batter. On August 23, Colgan went 2-for-5 with a double, 2 runs, and 3 RBIs in a 13-6 win over Columbus. This most likely amounted to his best game of the season. The Memphis club finish the year at 38-54 as the Southern League failed to last the season, calling off the last month of games and awarding the championship to Atlanta.

Billy Colgan was one of the first six men signed with Memphis for the 1886 season, the papers reporting that he “is in splendid trim and promises to do good work behind the bat.”4 In Nashville for an pre-season exhibition on March 18, he caught Alex Voss in a shutout loss but went 3-for-4 with a double. Flooding across the South in the spring had put Memphis’s field several feet under water, which led to a tough road schedule, but this hardship paled in comparison to the blow the team suffered on April 6. While Colgan was hunting small game with teammates and friends, he was accidentally shot by left fielder-pitcher Bob Black. According to the Daily Appeal, the accident happened as Colgan crossed a fence. “Catching hold of the muzzle of his gun, he passed it, butt first, through the crack of the fence, to his companion on the other side. It was accidentally discharged, and a charge of twenty-five buckshot, wads and all, entered his left side near the hip, passing through and lodging under the skin, whence they were afterwards removed by Drs. West and Crofford. The wound is serious, but is not likely to prove fatal.”5

Colgan was tendered at least two benefit games. The first, on April 30, pitted two amateur teams, the Bluff Citys and the Wrights, with a 25 cents admission charge. The Appeal called Colgan, “a noted catcher” and “a plucky and conscientious player.”6 In two updates, Sporting Life wrote first that “Colgan is doing fairly well; his wound is healing slowly,”7 then, “Colgan is umpiring fairly well. His gun-shot wound has healed, but is still tender.”8 It may have helped the healing process that Sporting Life reported at the same time that in Memphis, “the ladies stand is filled to ‘standing room only’ at every game.”

Colgan returned to the lineup on May 31, catching the very man who had shot him, Bob Black, and batting third, going 1-for-3 with two runs scored as Black hurled a three-hit shutout. On June 30, Colgan went 5-for-5 while catching O’Leary in a 5-4 win over Chattanooga.

Colgan was released by Memphis on July 21. It most likely spoke to Colgan’s character that Memphis held his roster spot at all. By August 11 the fully-healed catcher had been picked up by his old manager, Ted Sullivan, now with the Milwaukee Brewers of the Northwestern League. Colgan caught power pitcher Hugh “One Arm” Daily in an early September contest against St. Paul in which Daily struck out 10. Colgan had an RBI and a run scored, but was kept busy by three passed balls and two wild pitches.

Colgan was released by Milwaukee on September 7, and played the same day in a St. Paul Freezers uniform. The St. Paul Daily Globe paper called him “an excellent player [who] will strengthen the team.”9 He caught Jesse Duryea for St. Paul in a game Duryea lost to Milwaukee despite giving up only two hits. During the contest Colgan was declared out for being hit by a batted ball, and dropped a ball after being intentionally bowled over at the plate by James Sweeney for the first and decisive run of the game.

In late November of 1887, Colgan and Fleury Sullivan visited the office of The Sporting News, the paper stating, “Billy Colgan never looked so round, broad and fat as he does now.”10 The paper quoted Colgan as saying, “The St. Paul Club want me to catch for them again next summer, but between you and I, you won’t see this chicken playing ball again. I have started a saloon in East St. Louis and intend to stick to it.”11

Colgan is missing from the newspaper accounts of the day for much of the 1887-88 seasons. A March 23 note in Sporting Life said, “Colgan runs a paying saloon in East St. Louis.”12 At the tail end of 1887, Colgan again caught Jesse Duryea in St. Paul, and in March 1888 papers announced that in the coming season Colgan would catch for Denver.13 By December of 1888, one J.C. Mack of Homestead, Pennsylvania, advertised in the St. Paul Daily Globe “inquiring into the whereabouts of catcher Billy Colgan.”14 Sporting Life answered in print, “A letter to Mr. Colgan addressed care Sporting Life will no doubt reach him,”15 leading one to believe that Colgan was still behind the taps in East St. Louis.

In early April 1889, Colgan signed with Chattanooga of the Southern League. He showed no ill effects after presumably two years away from the diamond, spending much of the season batting second and stealing bases while alternating between the outfield and catching. Colgan cracked his second career home run on May 19, off Charlie Petty, and finished the season with 11 doubles, tied for third in the short-lived season as the league dwindled to three teams before collapsing on July 17. Colgan signed with Evansville of the Central Interstate League, but played in only five games and collected just one hit in 18 at-bats. Near the end of summer Sporting Life noted, “Catcher Colgan will have a winter berth with the Chattanooga fire department.”16

Signed by manager John Sloan Barnes of Spokane (Pacific Northwest League) for the 1890 season, Colgan caught on Opening Day, contributing a double and a run scored before the 1,800 in attendance. On August 20 Sporting Life reported, “[Lynn] Mills is doing all the catching at present, but Colgan is in good condition and is always ready to play. Why Manager Barnes doesn’t use him more is a puzzle to the cranks.”17 With a high-powered offense, Spokane finished the season 41-22 (.651). Sporting Life ranked Colgan fifth in batting among players appearing in 20 to 50 games. He batted a career-best .273 and scored 24 runs on 36 hits, with nine doubles, a triple, and 13 stolen bases. Colgan ranked third defensively among Pacific Northwest League catchers, posting a fielding average of .873.

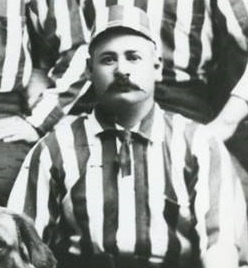

Shorty Colgan, as he was called in his season with Spokane, was one of the players who at the end of the season went to the papers in disgust over how manager Barnes had paid the players, in 30-day checks rather than cash, vowing not to play under Barnes another season. It is from this Spokane season that the only known photograph of Colgan was captured. He’s seated with his teammates in their thickly striped uniforms and hat, cross-legged with a fine mustache. He sits next to the team mascot, a behemoth of a St. Bernard named Prince.

Colgan spent his first of several offseasons working the railyards in Tacoma. But the ballfields were calling and Colgan signed with the first-place Walla Walla club of the Pacific Interstate League around June 25, 1891. On September 12, Walla Walla and La Grande were tied for first place, and there was chatter among the newspapers that Walla Walla, La Grande, or even Pendleton might have a better team than either Seattle or Tacoma of the Pacific Northwest League. Sporting Life wrote, “Billy Colgan, who did good work for Spokane last year, is doing first-class work for Walla Walla.”18 In a letter to Sporting Life discussing the final stages of the pennant race of the big brother and competing Pacific Northwest League, the unnamed Spokane Falls author asserts that, “the clubs of the Pacific Interstate League are having a monkey and a parrot time over umpires and players, to whose services there are rival claims, and the League is practically broken up.”19 While it may have been true that numerous players, and even some umpires had worked games in both leagues that summer, the Pacific Interstate League seemed to be a resounding success for the owners and enjoyable for the fans with a league made up of four relatively small towns. The games were competitive and well-attended with Sporting Life reporting that Walla Walla had a salary list of $900 a month and revenue of $500 to 800 a game with two games weekly. The Walla Walla team stuck together late into the fall, playing their last game on October 24. In November, Sporting Life reported, “Billy Colgan, the clever back stop, is brakeman on a passenger run on the Northern Pacific.”20

The Montana State League, the inaugural baseball league in Montana began play in 1892. Colgan was there suiting up on May 15 for Butte versus Missoula. A crowd of 1,200 saw Butte put on a first-inning hitting display that the Anaconda Standard described as “like a bucket of coal falling down the stairs.”21 A week later in Missoula, Butte and “Willie Colgan, who is a crack second baseman,”22 torched the home team 20-7, with Missoula’s catcher splitting a finger for the second week in a row. Two days later the Helena Independent reported that Colgan, who had by then signed with Missoula as a backup catcher, had been spiked and “is confined to a bed, and it is feared blood poisoning has set in.”23 The Standard said of the signing, “Colgan is a good catcher and a quick thrower and also a good striker.”24 Sporting Life opined that “the Missoulas have made a good move by adding ‘Billy’ Colgan to their list to hold down the second bag and change catcher. ‘Billy’ is a good man and has his eye on the sphere, as the Missoulas can testify by the way he rapped them out the two games he played for Butte.”25 Missoula, having fielded a much more hometown lot than the rest of the six-team league had opened the season 0-11 but, strengthened by Colgan, they won their first game on July 3 in front of 260 fans who, according to the Standard, “went wild. … They yelled, and screamed and cheered till they were tired.”26 Missoula was much more competitive in the second half of the split season, but never quite in the running and in the end Butte captured the pennant after Helena refused to play the deciding game of the championship series.

In mid-February of 1893, Colgan was in Great Falls, and writing a friend in Anaconda who informed the local paper that Colgan felt “the Cataract City [a long-lost nickname referring to the large waterfall on the Missouri rather than an eye condition] will make a big effort to get into the proposed intermountain league with Butte, Ogden, and Salt Lake.”27 After this correspondence, Colgan again went missing from newspaper baseball writings, but is presumed to be playing amateur ball in Great Falls, where on August 31, 1894, “the old prospector employed as switchman in the Great Northern yard was promoted to the position of foreman of the inside engines.”

In the summer of 1895, an item in Sporting Life mentioned Colgan among some baseball “old timers” in the Missoula area.28 Nineteen days after Sporting Life mentioned his name, on August 8, 1895, at approximately 1:20 P.M., William H. Colgan was crushed to death while retrieving coal cars from the Boston and Montana smelter on the Montana Central line of the Great Northern Railway. (The Boston and Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company would merge with the Amalgamated Copper Company in 1901, eventually becoming mighty Anaconda Copper in 1910.)

The American West was so young in 1895 that in the report on the coroner’s inquest, the word “Territory” has been scratched out next to the word “Montana” and replaced with the word “State.” Seven men testified at Cascade Country coroner Doc Weilman’s inquest: three fellow switchmen, the yardmaster, the on-duty engineer and his fireman, and a lawyer who happened to be walking by the yard at the time of the accident.

They described how Colgan was on the tail end of a row of dozen or more train cars that were being pulled across what was discovered to be a partially open switch. When the last coupling crossed the switch, it derailed, resulting in Colgan being pinned between the car he was riding on and a boxcar at a siding

The coroner’s jury ruled Colgan’s death accidental. News of his death was printed in at least four Montana newspapers, and again detailed in the Anaconda Standard’s 1895 “Montana Year in Review.” The Great Falls Weekly Tribune wrote, “Mr. Colligan (sic) was a strong and hearty man, full of life and energy, strictly sober and highly thought of by the railroad officials and respected and beloved by his fellow workmen and associates. He was greatly interested in athletic sports, especially baseball. He had been connected with a number of clubs and was a professional in this line. His uniform good nature and courtesy made him a favorite in the ball team as well as all who knew him.”29 These sentiments would be echoed almost verbatim in Fleury Sullivan’s obituary after he was murdered less than two years later.

Colgan’s remains were taken to W.C. McBratney’s undertaking establishment. McBratney advertised himself as the man who cremated the first three bodies west of the Rockies. The funeral was held on August 12 at St. Anne’s Cathedral, and was paid for by the Switchmen’s union. The half-mile-long cortege was populated by a large number of mourners who saw their friend, and the first former major leaguer to be buried in Montana, off to Old Highland Cemetery, where he wintered for 122 years under an unmarked grave. In the summer of 2018, a community-funded headstone in the shape of home plate was placed at Colgan’s grave.

A week before his death at the age of 33, Colgan was playing third base for a Great Falls town team against an aggregation from neighboring Sand Coulee when he hit a grand slam. In the home half of the fifth inning, Great Falls tallied seven runs, aided in large part by third baseman Colgan who, after Great Falls loaded the bases, “gave his bat a cyclone twist and the leather went about half way over to the B&M addition for a home run.”30

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on online newspaper archives including The Sporting News offered at Paper of Record, Sporting Life, as well as the Chronicling America newspapers hosted by the Library of Congress, including the Anaconda Standard, Butte Inter-Mountain, Dallas Daily Herald, Great Falls Tribune, Helena Independent, Memphis Daily Appeal, The Missoulian, Mower County Transcript, New York Tribune, Pittsburg Dispatch, Ravalli Republican, St. Paul Daily Globe, and Seattle Post Intelligencer. Additional information was verified in the player’s file at the Hall of Fame Museum and Library in Cooperstown. Census data was acquired from familysearch.org.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, February 20, 1897.

2 Mower County Transcript, December 26, 1883.

3 Sporting Life, June 17, 1885.

4 Sporting Life, February 17, 1886.

5 Memphis Daily Appeal, April 7, 1886.

6 Memphis Daily Appeal, May 22, 1886.

7 Sporting Life, May 5, 1886.

8 Sporting Life, May 26, 1886.

9 St. Paul Daily Globe, September 9, 1886.

10 The Sporting News, November 27, 1886.

11 Ibid.

12 Sporting Life, March 23, 1887.

13 The writer could not find any box scores to verify this.

14 St. Paul Daily Globe, December 9, 1888.

15 Sporting Life, December 5, 1888.

16 Sporting Life, April 14, 1889.

17 Sporting Life, August 20, 1890.

18 Sporting Life, September 12, 1891.

19 Sporting Life, October 10, 1891.

20 Sporting Life, November 23, 1891.

21 Anaconda Standard, May 16, 1892.

22 Anaconda Standard, July 1, 1892.

23 Helena Independent, May 24, 1892.

24 Anaconda Standard, May 29, 1892.

25 Sporting Life, June 11, 1892.

26 Anaconda Standard, July 4, 1892.

27 Anaconda Standard, February 19, 1893.

28 Sporting Life, July 20, 1895.

29 Great Falls Weekly Tribune, August 9, 1895.

30 Great Falls Weekly Tribune, August 2, 1895.

Full Name

William H. Colgan

Born

, at East St. Louis, IL (USA)

Died

August 8, 1895 at Great Falls, MT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.