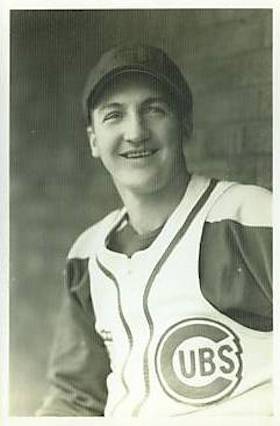

Bob Bowman

After Bob Bowman’s rubber-armed 1939 rookie campaign, St. Louis Star-Times sportswriter Ray J. Gillespie asked the 28-year-old to explain his remarkable endurance. In his folksy West Virginia drawl, Bowman made plain that “Pitchin’ every day beats workin’ in the [coal] mines, accordin’ to my way of figgerin’.”1 Having nearly led the St. Louis Cardinals to a National League pennant, Bowman’s 51 appearances undoubtedly beat laboring in the Atwater Pocahontas coal mines in the West Virginia coal country. But the cost to Bowman’s right arm was steep. When his major-league career ended three years later, he’d made just 58 more appearances. Worse still, for decades after Bowman’s exit from the game, he would not be remembered for his brilliant rookie campaign as much as for a single pitch thrown on June 18, 1940.

After Bob Bowman’s rubber-armed 1939 rookie campaign, St. Louis Star-Times sportswriter Ray J. Gillespie asked the 28-year-old to explain his remarkable endurance. In his folksy West Virginia drawl, Bowman made plain that “Pitchin’ every day beats workin’ in the [coal] mines, accordin’ to my way of figgerin’.”1 Having nearly led the St. Louis Cardinals to a National League pennant, Bowman’s 51 appearances undoubtedly beat laboring in the Atwater Pocahontas coal mines in the West Virginia coal country. But the cost to Bowman’s right arm was steep. When his major-league career ended three years later, he’d made just 58 more appearances. Worse still, for decades after Bowman’s exit from the game, he would not be remembered for his brilliant rookie campaign as much as for a single pitch thrown on June 18, 1940.

Robert James Bowman was born on October 3, 1910, the youngest of 10 children of Chester Bullard and Victoria Jane (Dickson2) Bowman, in the coal mining town of Keystone in McDowell County, the southernmost county in West Virginia. The Bowman family traced its roots close to Blacksburg, Virginia, in the late 18th century. During the Civil War Bob’s grandfather Samuel served in the Confederate army from Tazewell County. By 1870 Samuel had settled in McDowell County. Though Samuel never strayed from farming after the war, Chester and his sons all entered the mines. This included Bob who, after establishing himself as a gifted athlete as an American Legion hurler and two-time captain of the Elkhorn District High School basketball team, first entered the mines at 16.

Seeing an opportunity for an additional payday, Bowman quickly latched on with an assortment of regional semipro teams. His mound success spawned two brief opportunities in the pros. In 1929 Bowman secured a short stay with the Goldsboro (North Carolina) Goldbugs in the Class D East Carolina League. A longer trial with the 1934 Mount Airy (North Carolina) Graniteers in the Class D Bi-State League still ended in his release. Bowman returned to the semipro ranks. His experiences among the rough-hewn crowds were occasionally frightening. Pitching for a Jenkins (Kentucky) mine team in a grudge match against the nearby Lynch club, Bowman suddenly lost his control. He hit the first two batters. As Bowman later described it, “all hell broke loose. … I nearly died a martyr to baseball.”3 Fights broke out on the field and in the stands. A miner pulled a gun on Bowman but a quick-thinking teammate struck the gunman with a bat, dislodging the weapon from the assailant’s hands. State troopers entered the melee and shielded the Jenkins players as they exited the field. The troopers escorted Bowman and his teammates out of town in advance of a pursuing mob. Teammates and scribes marveled at Bowman’s cool, collected manner in the face of adversity. In light of such antics, pitching in the majors was a virtual walk-in-the-park for the self-described hillbilly. But he made a habit of declining all future invitations to pitch in Lynch, Kentucky.

In 1936 Bowman was persuaded by friends and family to attend an open tryout with the Albany (Georgia) Travelers, a Cardinals Class D affiliate. He caught the attention of scouts Charley Barrett and Joe Sugden. Bowman was selected as the starting pitcher in a spring exhibition between Albany and the Cardinals. His outing was short-lived when a line drive off Frankie Frisch’s bat broke the middle finger of his right hand. But the Cardinals were satisfied with what they saw. When the finger healed, Bowman was sent to the Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists (Class B Piedmont League) and finished the year with the Martinsville (Virginia) Manufacturers (Class D Bi-State League).

Varying accounts describe how Bowman surfaced with the Orr Cotton Mill club in Anderson, South Carolina of the semipro Anderson County Textile League in 1937. One says the Cardinals offered Bowman a return to Class B play with Mobile of the Southeastern League but with a pay cut. There is some question whether Bowman signed. Whether he did or not, he quickly bolted and secured a spot on his own in Anderson. Thomas K. Perry offers another view in Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880-1955, writing that Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey had an arrangement to send raw minor leaguers to get experience playing in the Anderson County League.4 By whichever means he arrived in South Carolina Bowman earned a return to the Cardinals fold after a successful 1937 campaign.5

Assigned to Rochester in the Double-A International League, the 27-year-old placed second among the Red Wings in appearances (48), working primarily from the bullpen. His 11 wins helped the team to a third-place finish, a sizable improvement from Rochester’s disappointing sixth-place standing the preceding year. When Ray Blades was promoted to manage the Cardinals in 1939, Bowman was one of the players he insisted accompany him to St. Louis.

The managerial vacancy was caused by the 1938 Cardinals’ dismal 71-win season (lowest over a 30-year span). The team’s hard-hitting offense – first in the league in runs scored – had been stymied by ineffective pitching that produced a poor sixth-place showing. As the Cardinals looked to overhaul their staff, hopes were placed on a rebound by Paul Dean and the emergence of their minor-league talent. As spring training progressed, Bowman and fellow rookie Mort Cooper received prominent attention.

Bowman’s sinking curve drew favorable comparisons to that of Adolfo Luque.6 Never one to shy away from self-promotion, Bowman felt the offspeed pitch was more like that of Dazzy Vance (later to be inducted into the Hall of Fame). With excellent control and deceptive speed, Bowman built an impressive Grapefruit League résumé, including two wins over the reigning champion New York Yankees. Among a strong 1939 freshman class entering the majors – among them Ted Williams, Charlie Keller, and Fred Hutchinson – Bowman attracted national attention.

Though his spring success caused some to project the “excellent young pitcher”7 as the Cardinals’ fourth starter, Bowman made his major-league debut from the bullpen. On April 21, in the second game of the season, he was inserted in relief against the Chicago Cubs and pitched three shutout innings in a losing cause. Two subsequent flawless outings earned Bowman a starting assignment in Boston on May 2. Facing a Boston Braves lineup containing two future Hall of Famers, Al Simmons and Al Lopez, Bowman held the Braves to six hits in his 2-1 victory, coming one out shy of a complete game. Five days later he suffered a 2-1 loss against the Brooklyn Dodgers despite surrendering just four hits in seven innings. Following another relief outing on May 10, Bowman possessed a 1.31 ERA in 20? innings. On May 21 he earned his first complete-game victory with a 5-2 win over the Philadelphia Phillies.

Used in relief with the occasional start, Bowman experienced some brutal outings as well. Unable to survive five innings against the New York Giants on June 17, he yielded six runs on nine hits, and his ERA rose to a season-high 4.37. A month later he encountered control problems in a start against the Braves that lasted just one inning, giving up two runs on two walks (no hits) in a 7-3 loss. But these outings proved atypical. Excluding the abbreviated July 15 start in Boston, from June 25 forward, Bowman proved nearly untouchable, posting a record of 11-1, 1.48 over 109? innings (33 appearances). A 60-38 surge by the Cardinals over the same period hoisted the team within 2½ games of the first-place Cincinnati Reds. Bowman relished the thought of facing the Yankees on his birthday in the World Series opener on October 3, but his hopes fell short when St. Louis was unable to close the gap further.

Bowman’s 2.60 ERA was second to the 2.29 of Bucky Walters, the league’s Most Valuable Player. (Bowman was the 30th of 32 players who received votes.) He was third among NL pitchers with 51 appearances. After the season Dick Farrington compiled a team of outstanding first-year players for The Sporting News. Though teammate Mort Cooper received the nod for pitcher over Bowman – a decision based on three more complete games, a rather dubious distinction considering Blades’ method of rotating pitchers – Farrington indicated that the choice was a sheer draw. He projected the righty as a future 18-to-20-game winner. When contracts arrived in the mail before the 1940 season Bowman got a raise plus bonus arrangements. The Cardinals rebuffed aggressive trade inquiries for Bowman from the Giants.

On March 29, 1940, Bowman turned in a fine performance in Havana in a 6-0 exhibition win over a Cuban team. He appeared poised to resume his place among the league leaders. But in early May Bowman was reported “out of commission”8 with an unidentified ailment. By May 10 he’d made only three appearances (4? innings) and had a dreadful 10.38 ERA. Though reports never specifically stated so, it appears the toll from overuse in 1939 was affecting the righty. The excellent control of the previous season had disappeared. After giving up only 141 hits in 169? innings in 1939, Bowman yielded 118 in 114? innings in 1940.

Things were going well for Bowman before a June 18 start against the Dodgers in Brooklyn. In four June appearances (three starts) he had collected two wins. On the morning of the 18th he entered the elevator of the Hotel New Yorker with some teammates and encountered Dodgers player-manager Leo Durocher and recently acquired (from St. Louis) outfielder Joe Medwick. Durocher said he did not plan to play that afternoon because of bruises received the day before. The brash righty popped off, “Of course you ain’t going to play. You know I’m going to pitch.” Durocher prophetically replied, “You won’t be in there when I get to bat.”9 Tensions continued until Bowman was heard shouting, “I’ll take care of you! I’ll take care of both of you!”10

After Bowman surrendered hits to the first three batters he faced, Medwick came up. The first pitch to the cleanup hitter struck him behind the left ear. Carried off the field on a stretcher, Medwick was taken to Brooklyn’s Caledonian Hospital and diagnosed with a concussion. Meanwhile turmoil prevailed on the field. Convinced the beaning was intentional – an extension of the elevator encounter – the Dodgers sought revenge. Team president Larry MacPhail stood before the Cardinals dugout threatening to take the players on individually or collectively. The umpires restored order before fists were thrown and the game resumed after Bowman’s retreat to the showers. In a statement to sportswriters, MacPhail accused Bowman of cowardly actions. As Bowman left the ballpark under police escort, MacPhail sent a wild swing at the pitcher.

After an investigation, National League President Ford Frick absolved Bowman of intent. But the matter quickly moved into the realm of the bizarre when District Attorney William O’Dwyer announced his own investigation into criminal intent. A congressman from New York threatened to introduce legislation banning the beanball. Neither of these developments gained much traction. The day after the game Durocher exchanged heated words with Cardinals players over breakfast at the Hotel New Yorker. At the game that night he had a fistfight with Cardinals catcher Mickey Owen, who was ejected. Matters settled down after manager Billy Southworth – who’d replaced Blades following a dismal start to the season – went to the hospital and conveyed to Medwick his team’s regrets over the incident. Medwick returned to the lineup within days and resumed his Hall of Fame career for eight more seasons. But his home-run production slowed. Many chalked this up to the beaning.

On June 23, in his next appearance, Bowman faced only two Braves batters before leaving with an injury. He sat for 26 days. Bowman registered a record of 5-2, 4.44 over his final 14 appearances. Over this course his relationship with Southworth soured. (The author was unable to determine if this was tied directly to the Medwick incident.) After the season, in what many considered a surprise move, Bowman was sold to the Giants for an estimated $35,000. Though the team did not have pitching to spare, Cardinals majority owner Sam Breadon stated, “We decided that it would be for the best interest of the club to send [Bowman] elsewhere.”11 (The reference was to the Bowman-Southworth breach.)

The Giants were elated to have secured the coveted righty. With Bowman and other new faces, the team envisioned pennant contention in 1941 after a sixth-place finish in 1940. In spring training, they stayed at the swanky Miami-Biltmore Hotel, next to a golf course on which Bowman and other Cardinals played. On the baseball field Bowman did not disappoint. On March 20 he twirled a superb six-inning stint against the Reds. Sixteen days later, as the team played its way north to start the season, Bowman hurled a shutout over the Atlanta Crackers.

The Giants got off to a sizzling 8-2 start to the season with Bowman contributing wins in his first two starts. But the fates of team and hurler both turned south. Following a dreadful July that included a six-game losing streak, the team finished in fifth place 25½ games behind the first-place Dodgers. Bowman’s season largely paralleled this trend. On April 29 he absorbed his first loss to his former team, chased after four innings. He managed just one inning in his next start. Relegated to the bullpen, Bowman began to right himself. Except for a rough outing against the Reds on June 15, from May 22 Bowman had a 1.20 ERA over nine appearances (15 innings) that likely contributed to manager Bill Terry’s decision to return him to the rotation. But after two consecutive losses in August, he was again banished to the pen. After once great expectation, Bowman finished the season 6-7 with a 5.71 ERA in 29 appearances. On December 3 he was traded to the Chicago Cubs for outfielder Hank Leiber and $20,000.

Bowman’s reception in Chicago appeared less than welcoming. When rumors surfaced over the winter that he’d signed a Cubs contract for the 1942 season, general manager Jim Gallagher declared that the trade was only conditional. Should the Giants release Leiber, Bowman would be returned to New York. And as it turned out, Bowman pitched in just one game for the Cubs, a one-inning mop-up appearance against the Cardinals on May 25 – his last game in the majors. He was assigned to the Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League. On June 21 he earned Toronto’s only 1942 victory in Montreal. But his 5.75 ERA spelled little success. In late July Bowman was optioned to Nashville of the Southern Association, whose manager, Larry Gilbert, said: “If Bowman can pitch like I think he can, then we’ll be tough going to the wire.”12 The righty did not disappoint, winning his first six decisions over a 17-day span. His assistance from the bullpen helped lead the Volunteers to the Southern Association championship and victory over the Shreveport Sports in the Dixie Series.

In November Bowman was reinstated on the Cubs roster. Over the next two years Chicago sold or traded him to two Pacific Coast League teams – the Hollywood Stars in 1943 and the Los Angeles Angels in ’44. In both instances Bowman refused to report and threatened to retire. He toiled instead in the American Association with Milwaukee and Minneapolis in 1943 and 1944. Purchased by Buffalo of the International League in March 1945, Bowman was the Opening Day starter in a 19-5 rout suffered at the hands of the Syracuse Chiefs. The loss mirrored Bowman’s season with the Bisons. He went 5-10 with a dismal 5.79 ERA.

Bowman might have considered retirement had it not been for the emergence, re-emergence, and expansion of the Class D Western Carolinas, Blue Ridge, and Appalachian Leagues. They provided him the opportunity to continue play close to his West Virginia home from 1946 to 1951. On August 20, 1947, he pitched a no-hitter for Mount Airy of the Blue Ridge League against the Galax Leafs. Two days later Bowman and manager Chubby Dean were fined and suspended – later reduced to probation – for using obscene language. On September 3 Bowman replaced Dean as interim manager when Dean was released after a playoff loss.

In 1948 Bowman split his time between Mount Airy and, beginning July 29, as player-manager for the Morganton (North Carolina) Aggies in the Western Carolinas League. On August 12 he engaged in a heated argument with umpire Arthur Talley. The umpire, a former Gastonia, North Carolina, policeman, was charged with assault after striking Bowman with a soda bottle. He was compelled to pay $15 in undisclosed medical fees. Three years later Bowman signed as manager of the Norton (Virginia) Braves in the Mountain States League. The stint lasted just 36 days; he was released on June 2.

Bowman retired and likely returned to the 45-acre farm he’d bought near McComas, West Virginia, with his 1939 baseball earnings. As he’d done every offseason, he returned to the mines, this time on a regular basis. He had married Beulah Evans, the daughter of the mine’s bookkeeper, and they raised a daughter and son. Beulah died in 1958. Two years later Bowman moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and was employed by the city’s municipal recreation department. He married Marion Wood. In the summer of 1972, after returning to his native state to take care of some personal matters, he fell seriously ill. Admitted to Bluefield Sanitarium, Bowman died on September 4, 1972. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Bluewell, West Virginia, survived by his second wife, two children, and two grandchildren.

As a 28-year-old rookie, Bowman entered the major leagues in 1939, making a large splash. Called upon every third day on average, he helped as the Cardinals challenged for the pennant. But his workload took its toll on his pitching arm. Bowman was never going to remain in the majors as a hitter. He once held the record for the highest percentage of strikeouts (.604) of any hitter with 75 or more at-bats. But for a fleeting period, Bowman was one of the most dominant pitchers in the National League. He possessed a sinking curveball and was compared to some of the great hurlers in baseball. But Bowman’s accomplishments were eventually overshadowed by an errant pitch that nearly ended Joe Medwick’s career.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Christopher E. Bowman, Bob’s distant cousin, for assistance with the Bowman family history. Further thanks are extended to Len Levin for editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

Ancestry.com

sabr.org/bioproj/person/92a8ae6f

findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=37770077&ref=acom

Wolinsky, “Ray Blades.” SABR Baseball Biography Project

Notes

1 “Pitchin’ Every Day Beats Working in the Coal Mines,” The Sporting News, December 21, 1939, 3.

2 Elsewhere found as Dickerson or Dixson.

3 “Pitchin’ Every Day.”

4 Thomas K. Perry, Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880-1955 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2004), 58.

5 Yet another account indicates Bowman was re-signed by scout Frank Rickey, the general manager’s brother, after Branch pleaded with the hurler to return.

6 In 1941 Luque was one of Bowman’s coaches in New York.

7 “Help Being Awaited by Grounded Wings,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1939, 9.

8 “Fans Lose Patience With Cards and Boo at Hurling Changes,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1940, 1.

9 “ ‘Pass Bean-Ball Rule in N.L.’ – Ducky; Frick Favors Helmets,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1940, 3.

10 Charles F. Faber, “Joe Medwick.” The Baseball Biography Project, Society for American Baseball Research.

11 “ ‘Hard To Get Cash,’ Breadon Declares of Big Money Deals,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1940, 1.

12 “Vols Get Erickson, Bowman From Cubs in McCall Deal,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1942, 1.

Full Name

Robert James Bowman

Born

October 3, 1910 at Keystone, WV (USA)

Died

September 4, 1972 at Bluefield, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.