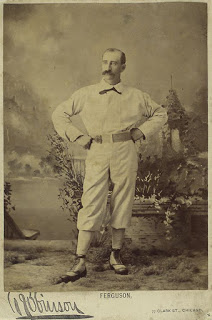

Bob Ferguson

Bob Ferguson, one of the most respected and influential baseball players of the 19th century, was the game’s first switch-hitter. He may not have done it regularly and, surprisingly, he didn’t do it for the reasons hitters do today; he didn’t switch-hit depending on whether the pitcher was right-handed or left-handed. (At the time, there were few lefties of consequence.) Ferguson switched between batting left-handed and right-handed for situational reasons or according to how he felt at a particular moment.

Bob Ferguson, one of the most respected and influential baseball players of the 19th century, was the game’s first switch-hitter. He may not have done it regularly and, surprisingly, he didn’t do it for the reasons hitters do today; he didn’t switch-hit depending on whether the pitcher was right-handed or left-handed. (At the time, there were few lefties of consequence.) Ferguson switched between batting left-handed and right-handed for situational reasons or according to how he felt at a particular moment.

The first time of significance was on June 14, 1870 — even before the formation of the old National Association. Ferguson was a player for the Brooklyn Atlantics. On that day, Ferguson, a Brooklyn native and already an established star in New York, attracted national attention for the first time. The day was significant because it marked the beginning of the end of the reign of the Atlantics’ opponent, the fabled Red Stockings of Cincinnati.

The Red Stockings hit Brooklyn riding an 81-game winning streak. They hadn’t lost since October 1, 1868, when they fell to the Atlantics. During the streak, the Red Stockings crushed the Atlantics in 1869. Regardless, the National Association of Base Ball Players, the game’s umbrella group at the time, named the Atlantics champions in 1869. The 1870 rematch caught the attention of the baseball community; the declared champions versus the best team in the country.

It was a well-played game, only three errors. The crowd reached upwards of 20,000, standing room only, long before game time. At the end of nine innings at Brooklyn’s Capitoline Grounds, Cincinnati and the Atlantics were tied at five runs apiece. Reds captain Harry Wright wanted to continue the contest. Ferguson, Brooklyn’s captain and catcher, was happy to finish with a draw against the great Red Stockings after his club rallied to tie the contest. The pair discussed the matter with baseball authority Henry Chadwick, who was on hand. Chadwick, chairman of the rules committee of the Association, ruled that the game must continue. The Reds scored twice in the top of the 11th, but in the bottom of the inning Ferguson came to bat with his club down only a run.

With the game on the line, a particularly tense and significant game for that matter, Ferguson, a natural right-hander, took his stance on the left-hand side of the plate. Surely this was done with a great deal of nerve and confidence, but it was also a high-risk maneuver. So why did Ferguson do it? He wanted to keep the ball away from the Reds’ great shortstop, George Wright. He also wanted to shake up the opposition. It worked; Ferguson poked the ball to the first-base side, where it went through the legs of first baseman Charlie Gould into right field, knocking in Joe Start with the tying run. Ferguson kept running and scored the winning run when Gould threw the ball over the third baseman’s head. The fans rushed the field and carried many of the men off on their shoulders. “The yells of the crowd could be heard for blocks around, and a majority of the people acted like escaped inmates,” the New York Sun wrote. Reds president Aaron Champion cried when he wired the news of the loss back to Cincinnati. Jubilant, the directors of the Atlantics awarded each player $364.

Robert Vavasour Ferguson was born on January 31, 1845, in Brooklyn, New York, to Irish natives Hugh and Sarah Ferguson. Hugh supported the family as a day laborer. The Fergusons had three other children: Sarah Jane, born around 1835; John, circa 1841; and Thomas, circa 1845. Sarah’s name was actually Sarah Johnson. She may have been an extended-family member incorporated into the family, or she may have been Sarah Ferguson’s child from a previous marriage.

Robert attended local schools in Brooklyn. Though he was old enough, there is no record that he served during the Civil War. He began playing ball during the amateur era and it seems that he didn’t use a glove during his career. Ferguson threw right-handed, stood 5-feet-9½, and weighed about 150 pounds through much of his career. Though he batted mostly right-handed, he hit from the left side of the plate more and more as his career progressed in the National Association and the National League.

Ferguson joined the Frontier Club of Brooklyn as early as September 1863 at the age of 18. That month, he pitched for the club. Frontier was a junior club for younger or inexperienced players who hadn’t found a slot on a senior club. The team was a member of the Brooklyn Junior Association. Ferguson returned with the club in 1864, mainly playing in the infield. Even at 19, he was taking control of the clubs he played for; that summer, he served as captain during a picked contest of Brooklyn junior stars, a local, informal all-star game. By September, he found a slot on a senior club, the Enterprise of Brooklyn, a member of the ruling body of the day, the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP). It’s unclear whether he played in any formal NABBP games that season.

Ferguson played third base and shortstop for Enterprise throughout 1865, including five games within the NABBP structure. The club was among the weaker ones in the New York area in league competition, winning only one of 11 contests. Perhaps as a result, Ferguson looked elsewhere and jumped teams in 1866. Ferguson landed with the famed Atlantics of Brooklyn. The Atlantics were formed in August 1855 and, being acknowledged as the champions from 1859 to 1861, were the sport’s first dynasty, one that included the famed James Creighton.

Ferguson had an inside connection with the Atlantics that may have been the reason he chose the club and vice versa. In November 1860, his sister, Sarah, married Thomas Tassie, one of the founding members of the Atlantics and an active participant in club matters throughout its existence during the amateur era. Tassie was president of the Atlantics in 1857, 1858, 1869, and 1870. He was a delegate at the formation of the NABBP in 1857 and was named president of that body for 1869. Tassie was a member of the rules committee of the NABBP for several years, starting at its inception. As such, he worked with Doc Adams and others who are generally credited with creating the crux of the rules of the day. During the Mills Commission’s investigation at the turn of the century into the origins of baseball, Tassie was among those consulted on certain issues relating to the game’s development.

Ferguson joined a championship club, one that was declared NABBP champion in 1864 and 1865. The Atlantics rode a 36-game winning streak until June 1866. They won the title again during Ferguson’s first season, with a 17-3 record, and again in 1869. Ferguson appeared in 18 NABBP games in 1866 as well as numerous nonleague contests, primarily manning third base and the outfield. He remained with the Atlantics until the formation of the professional National Association in 1871. Dan McDonald, Dickey Pearce, Joe Start, and George Zettlein played on the team every year during that span. Jack Chapman, Fred Crane, John Kenney, Charlie Mills, Tom Pratt, and Charlie Smith were Atlantics with Ferguson for at least three seasons. Lip Pike joined the club in 1869 and George Hall the following year.

With the Atlantics, Ferguson became known as one of the finest fielders of the day, making an impact at several positions. For example, after a big game against a staunch rival, the Mutuals of New York, on August 12, 1867, the Brooklyn Eagle commented, “Ferguson played third base, and marked the game by an elegant left hand fly-catch that surprised himself as much as it surprised the spectators.” On October 2, 1873, after a game in which Ferguson had a total of 11 putouts and assists from third base, the Eagle wrote, “Ferguson … playing with sore hands, fielded in masterly style, his picking up of hot ground balls being done in the best style of art; a line ball catch, too, elicited loud applause.” The examples show how he might have gained the odd yet fitting moniker Death to Flying Things, a nickname also bestowed on teammate Jack Chapman, an outfielder and first baseman. At various times during his career, Ferguson was also called The King of Third Base, Richard the Great. and other more mundane nicknames such as Fighting Bob, Base Ball Bob and Fergy.

In 1870 the Eagle wrote of Ferguson that he “played short in truly a masterly style.” That year and the previous one though, he mainly played behind the plate, typically catching George Zettlein. Ferguson was among the first wave of catchers to move closer to the plate. Traditionally, the catcher stood perhaps 20 feet behind the batter and caught the ball on a bounce. Ferguson and others during the late 1860s started creeping closer, sometimes with hazardous effects. The July 30, 1869, game against Maryland is an example. Wrote the Eagle: “In the fourth inning, Ferguson was quite badly injured. While playing closely to the bat, he was struck on the nose, by a sharp tip ball, fairly knocking him down. That organ swelled up to twice its usual size, and completely altered the appearance of the man. Fortunately the injury is not a permanent one, and Fergy’s good looks will be spoiled only for a day or two at the most. The pain was severe, yet he kept at his post pluckily, except for one inning, when the blood flowed so freely that he could not play.”

In 1867 and ’68, Ferguson played mostly at third base. In the latter year he appeared in 51 games in NABBP competition, led the league in total bases, and finished third in hits behind teammates Start and Chapman. In 1869, the NABBP permitted openly professional clubs for the first time. The Atlantics were among the first to declare themselves as professionals. Ferguson became the club’s captain and switched to catcher for two seasons. He would manage most of his clubs through the rest of his career.

In an early example of tense player-media relations, Ferguson threatened to “knock every tooth out of the head” of a critical New York Herald reporter in 1870. That season saw the Atlantics’ monumental defeat on June 14 of the Red Stockings. During its winning streak, Cincinnati had defeated Atlantics 32-10 the year before, on June 16, 1869. On July 4, 1870, Fergy notched one of the top batting games of his career. Against the White Stockings of Chicago in Brooklyn, he knocked three home runs in his first three at bats, including a grand slam and a three-run shot, and also placed a triple. He scored five times and Brooklyn won, 30-20.

At the end of 1870, the NABBP was in turmoil as internal factions, torn between amateurism and professionalism, fractured the organization. The directors of the Atlantics decided to shed the club’s professional members and entered the new National Association of Amateur Base Ball Clubs in March 1871. Sensing the upheaval, Ferguson had already departed as some of the stronger professional clubs formed the National Association. The age of open and respected professionalism was born. Ferguson negotiated for a spot with the Philadelphia Athletics, Chicago White Stockings, and New York Mutuals. He insisted that Joe Start and Charlie Smith accompany him. Fergy worked out a lucrative deal with Chicago but in the end Start insisted on remaining in New York. The Chicago club blasted Ferguson in the press but he was nevertheless headed to the Mutuals, signing in January.

On January 12, 1871, Ferguson and members of the Atlantics and Mutuals played a baseball game on ice with skates, the first such game in New York City in three years. Ferguson pitched. He also played ice baseball during the following winter. Former Atlantics Start, Smith, and Dickey Pearce joined Ferguson with the Mutuals. Fergy played third base, caught a little, and also tried his hand at second. Around this time, though he was a teetotaler, he opened a saloon in Brooklyn. (He did, however, smoke heavily.) Ferguson quit the business after a fight with a drunken friend when Ferguson refused to serve him. “This life is too unclean for me,” he exclaimed.

Professionalism was indeed here to stay. The directors of the Brooklyn Atlantics soon realized this; on May 8, 1871, they were crushed by the Boston Red Stockings, 25-0, their worst defeat in history. The club soon joined the National Association for 1872, re-adopting professional players. Since the reserve clause wasn’t in existence then, men were free to move from club to club. Ferguson was delighted to return to the Atlantics as player-manager. The Mutuals, who had a reputation of gambling and game-fixing with Tammany’s notorious Boss Tweed at the helm, probably were not his cup of tea.

On March 7, 1872, Ferguson attended the annual meeting of the National Association in Cleveland as a delegate for Brooklyn. The delegates firmly believed that the Association’s president should be a player. Alex V. Davidson of the Mutuals offered Ferguson’s name for nomination and he was elected president, a position he held for two years. The position was largely ceremonial but Ferguson conducted league business as he traveled to the Association’s games during the season. He thus became the only man in baseball history to simultaneously serve as player, manager, umpire (which he did on occasion), and league executive. One of his major stances as National Association president was to declare that player misbehavior and contract disputes were strictly under the purview of individual clubs, and hence not a concern for the Association as a whole.

(As president, Ferguson was aware of the troubles that plagued the National Association, such as players revolving (jumping clubs), scheduling difficulties, and the ever-present and often dominant gambling attractions – pool selling, bookmaking, side betting and direct betting — which at times led to game-fixing. Ferguson in fact faced down the gamblers and became noted in Al Spalding’s words as “a man of sterling integrity and splendid courage.” However, Ferguson was just one man and his plate was full. No one stood beside him in an effort to eliminate the gambling element. Also, as Spalding noted, Ferguson “lacked the essential qualifications of a reformer.” These issues among others led to the demise of the National Association and the formation of the National League in 1876. As a director of the National League, he did indeed help usher gambling to the side in the wake of the Louisville Grays’ fiasco in 1877 — when, it should be noted, he had others finally standing by his side.)

When he took over the Atlantics in 1872, Ferguson was unable to entice any of his cohorts to join him. On Opening Day, May 2, the field included Fergy and eight newcomers to the big-time professional level, most of them in their early 20s. Most were holdovers from the 1871 amateur club. The Atlantics’ only pitcher was Jim Britt, a 16–year-old from Brooklyn. The club finished with a poor 9-28 record, well behind pennant-winner Boston. Twenty-two-year-old left fielder Al Thake drowned on September 1 while fishing off Fort Hamilton in New York Harbor. Ferguson organized one of the first benefit games for a player’s family, an old-timers game. On October 23, members of the 1869 Atlantics and the Red Stockings met. Unfortunately, poor weather limited the payout to Thake’s mother to $200.

Dickey Pearce, who played with the Atlantics from 1856 to 1870, rejoined them in 1873 but the team fared poorly again. Britt led the league in starts and complete games but had a meager 17-37 win-loss record. The team finished in sixth place again. Ferguson was the only man to spell Britt on the mound, starting one game and relieving in three others for a total of 19 1/3 innings and a 0-1 record. Ferguson was a tough competitor and could be a handful on the field. Despite being the Association’s president, he wasn’t above abusing umpires. On June 2, he even walked out of a game in a dispute with one. Outside Brooklyn, Ferguson, as a league official, was blasted by the press for such departures from decorum. A lapse on July 24 at the Union Grounds in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, stands as a prime example of on-the-field violence during the game’s early years.

On July 4, the Atlantics had lost to the Mutuals. Heavy suspicion fell on several Atlantics members who allegedly tanked the game at the behest of local gamblers. On the 22nd, the Atlantics played Baltimore in Brooklyn, losing 12-9. After the contest, Ferguson approached the pool-selling (gambling) area and faced the gamblers. As reported in Wilkes’ Spirit, he challenged the men, “I’ve marked you, you infernal (we draw the adjective mild, for fear of offending polite ears) thieves and robbers. I’ll bust you yet, and drive you out of here, you contemptible scoundrels, thieves and blackguards. I’ll teach you to buy my men, you low-lived loafers — every one of you. There ain’t one of you who wouldn’t steal a penny from your dead mother’s eyes, and kick the corpse because it wasn’t a quarter. Come out here, if you want to, any one of you who don’t like it, or whom the coat fits, and I’ll warm the ground with your miserable carcass till you won’t want to buy up my men again.”

The Brooklyn Eagle applauded Ferguson’s efforts, opining, “This is the first instance on record that either a player, a captain of a club nine or the manager of any professional club, has had the moral courage to boldly and publicly denounce the gambling frauds which have brought such odium upon professional playing. … Captain Ferguson certainly deserves great credit for thus boldly facing these knaves as he did.” The incident is at the root of the reputation Ferguson developed as one of the most honest and respectable men during such a tainted era.

On July 24, Ferguson was umpiring a contest between the New York Mutuals and the Baltimore Canaries. This was nothing new; he had been filling in as a substitute umpire for years. New York won 11-10, scoring three runs in the ninth to claim the victory. Near the end of the contest, Ferguson picked up a bat and swung it at Mutuals catcher Nat Hicks. As the Brooklyn Eagle described it, “The occurrence took place during the interim between the first and last part of the ninth inning, when [Mutuals third baseman John] Hatfield and Hicks were engaged in mutual recriminations in which charges of foul play were made, and on a remark being made by Ferguson that Hicks’ play looked to him as if he wanted the Mutuals to lose [Hicks had made an error in the ninth at a time when the club was losing]. Hicks replied by calling Ferguson ‘a d—n liar.’ ” Just then Ferguson, on the impulse of the moment, picked up a bat nearby and struck quickly at Hicks, but had not Hicks put out his arm the bat would not have reached him. As it was, the end of the bat simply bruised the skin, causing blood to flow and giving the appearance of an ugly wound.”

The Eagle spun the incident a little. Ferguson in fact cracked Hicks’ arm, breaking it. As was normal among tough competitors, Hicks didn’t make an issue of the event after the contest. Nonetheless, it was a brutal action on Ferguson’s part and one that would be swiftly and severely dealt with today by league administrators. However, Ferguson was in fact the league president and the issue wasn’t pursued. Of course, no one authoritatively called for action against Ferguson — not Hicks, the Mutuals, or sportswriters. It was a tough era.

At the end of the game, the fans stormed the field. Police surrounded Ferguson and one of them handed him a bat as they made their way off the field. For his part, Ferguson apologized and, dismayed, swore off umpiring. The incident, clearly Ferguson’s doing, was exacerbated by the gambling stink surrounding the scandalous Mutuals. Even some of the Atlantics came under suspicion in 1873. Hicks, a tough catcher and a Civil War veteran, missed two months, the longest absence of his career. The Mutuals had to cancel a scheduled Southern tour. They played on July 26 with Dick Higham at catcher but then didn’t suit up for another National Association contest until August 7.

In early 1875, the balding Ferguson left the Atlantics to join the Hartford Dark Blues, a club run by Morgan Bulkeley of Hartford, an Aetna Insurance Company heir with longtime business connections in Brooklyn. Once again, Ferguson was named player-manager, still primarily manning third base. Further devastating the Atlantics, Ferguson enticed pitching ace Tommy Bond to switch clubs as well. Ferguson had inserted the 18-year-old Bond, an Ireland-born Brooklyn resident, into the Atlantics rotation in 1874. In all, Hartford fielded six men from Brooklyn, four of them former Atlantics. As a result, the Atlantics collapsed, posting a pathetic 2-42 record in 1875. Bond and Ferguson roomed at the elegant United States Hotel in Hartford all summer. Hartford pulled another coup, luring curveball specialist Candy Cummings from Philadelphia. Cummings, also a Brooklyn boy, won 35 games and Bond 19 to help Hartford land in third place, though well behind pennant-winner Boston.

On August 12, Ferguson showed another aspect to his switch-hitting; he did it according to how he felt at the moment. He came to bat with two outs in the ninth, his team down a run, and a runner on third. He fouled off several pitches batting left-handed against New York Mutuals right-hander Bobby Mathews. Fergy then jumped into the other batter’s box and poked a hit over the third baseman’s head to tie the game. It ended that way. As far as switch-hitting goes, this was still pretty early in its evolution. Lefty-righty considerations wouldn’t come into vogue until the late 1870s.

The National Association didn’t survive to see the 1876 season. Bulkeley and Ferguson entered the Hartford club in the new National League. Bulkeley was named the league’s first president; Ferguson became one of its four directors, along with Charles Case of Louisville, Nicholas Appolonio of Boston, and Charles Fowle of St. Louis. Ferguson’s years with Hartford, 1875-77, were his best as a manager; the club finished third in each season.

Ferguson was one of the early masters of the trapped-ball play. The maneuver proved useful after the fly rule took effect in the mid-1860s. That meant that outs were no longer recorded for one-bounce catches, only for batted balls caught on the fly. Hence, room for a little trickery opened. Eventually, the infield-fly rule would counter the move. Ferguson pulled off the first hidden-ball trick in National League history on May 25, 1876. The victim was Cap Anson of Chicago. In the seventh inning Ferguson, playing third base, received the ball on a relay from the outfield without Anson noticing. When Anson casually stepped off the bag, Fergy applied the tag.

In 1876, Ferguson experienced the first major backlash from his players over his dictatorial, domineering, and overbearing management style. He expected nothing less than 100 per cent obedience from his men. He was stubborn, quick-tempered, and hot-headed; as a consequence, he was disliked by many. As Philadelphia manager Al Wright put it, “Bob Ferguson plays a good game when he does do it; but, oh! How he can muff and growl.” Sam Crane wrote of Ferguson, “Turmoil was his middle name, and if he wasn’t mixed up prominently in a scrap of some kind nearly everyday, he would imagine he had not been of any use to the baseball fraternity and the community in general.” The Sporting News put it this way: “Ferguson had few friends among the players. He was a man of too blunt ways to cultivate friendships of many and he courted the ill rather than the good will of his fellow men.” A striking example of this could be boldly seen on his very person. With Hartford, he wore a white belt with the words “I AM CAPTAIN” in capital letters just in case someone was unsure of who was in charge. The Brooklyn Eagle exclaimed, “Ferguson is the sternest manager in the country.” Naturally, this tended to alienate the other men on the field. The New York Clipper took it a step further: “He is a bully who most players are afraid of and consequently none respect.” The issue boiled over on August 19, 1876.

Ferguson had a bad day at third base, making several errors. The team lost to Boston 13-4. Tommy Bond accused his manager of “crooked work.” Ferguson denied the charge and Bond quickly retracted his statement. In all likelihood, Bond was frustrated with his tyrannical manager and wanted away from him. The pitcher, now 20 years old, was tired of being under Ferguson’s thumb for the last three seasons. He asked Bulkeley for his release and it was granted. Bond had shined at the beginning of the year and was handed the ball day in and day out, relegating Candy Cummings to the sidelines. When Bond left, Cummings finished out the schedule. But regardless of the troubles with his personnel, Ferguson was well-respected throughout the industry and always would be. For example, the Brooklyn Eagle commented in 1877 that “Ferguson stands now next to Harry Wright as a skillful manager of a team.”

After the 1876 season, Ferguson had a busy winter. First, he had to replace Cummings, who was nearing the end of his career. Hartford landed another young Brooklyn guy, Terry Larkin, who had pitched and lost one game for the New York Mutuals in May 1876. Second, Ferguson organized the relocation of the franchise. The Hartford club relocated to Ferguson’s hometown of Brooklyn for the 1877 season, becoming the first major-league club to do so. The team played at the Union Grounds and was renamed the Hartfords of Brooklyn. The Hartfords played one game in Connecticut that season.

By 1877, Ferguson, the manager, was developing a new defensive strategy to counter pull hitters. He started to shift the second baseman to the left side of the field against certain hitters and rearranging his outfield. He soon started to do a similar maneuver as left-handed pull hitters became more prominent in the game. The Louisville Courier Journal wrote after Hartford defeated the Louisville Grays, 12-2, on May 18, “One of the most curious features of the Hartfords’ play is the way Ferguson has of shifting his men from one position to another for the accommodation or rather inconvenience of the different opposing batsmen. When [right-hander Jim] Devlin comes to bat [left fielder Tom] York is motioned to play deep left field, [center fielder Jim] Holdsworth edges toward left, [right fielder Bill] Harbridge takes a stand in the center fielder’s dominions, right field is left to itself for the time being, Devlin hits a mighty lick, and it is ten to one that York nips him on the fly. Many years’ active service on the ball field has given Ferguson an excellent opportunity for studying batsmen, and he has not failed to profit by it. No nine in the country last season excelled the Hartfords in fielding, and Ferguson was at the bottom of it all.”

Within a couple of years, Ferguson was taking his shifts a step further. For example, against some left-handers he would shift the entire field. The third baseman manned the shortstop’s position. The shortstop played behind the second-base bag. The second baseman moved back into the outfield and the first baseman played well back of the bag. The right fielder hugged the line with the center fielder playing right-center and the left fielder playing left-center. Similar shifts seem common today but in the 1870s they were quite the marvel.

After two years of meager attendance in the National League, Morgan Bulkeley disbanded the Hartford franchise. On November 12, 1877, Ferguson signed with the Chicago White Stockings as their new player-manager, his only season away from the East Coast. Club president William Hulbert inked him at the behest of Al Spalding, who held Ferguson in high regard and admired his intensity and fiery management style.

But 1878 was a rocky season from the start. Ferguson installed himself at shortstop, despite having played the position only sparingly over the previous decade. He brought in his old friend Joe Start to play first base and signed Frank Hankinson for third. This pushed Cap Anson into left field; the only time in his career he didn’t predominantly man an infield position. Terry Larkin also came over from Hartford but managed just a 29-26 record. Ferguson, though, had his finest year with the bat; he hit .351, third in the league, in 61 games, and led the league in on-base percentage. Despite leading the league in runs scored, hits, batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging, the White Stockings finished with a .500 record, 30-30, in fourth place of six teams.

Many saw the season as a glowing failure of Ferguson’s. He had a talented squad but couldn’t lift them to near the top of the standings. Hulbert meddled all season, and Fergy rode his men hard, too hard in the opinion of many. He abused his men and wore out his welcome in Chicago. Even Spalding, who had lauded his style, later complained about Ferguson in America’s National Game, “He was no master of the arts of finesse. He had no tact. He knew nothing of the subtle science of handling men by strategy rather than by force.” Spalding’s book captured Ferguson rather fairly. In one light he was roundly praised and respected for his accomplishments and contributions to the game. In another light, he was chastised for his overbearing nature. After the season, Anson was named manager and planted himself at first base for the next two decades.

Ferguson was named player-manager of Springfield, Massachusetts, in the minor National Association for 1879. He appeared in 15 games with the club, missing time due to illness. He left the club by early July and spent the month umpiring. On August 7, he took over management of the weak Troy franchise of the National League and appeared in 30 games, mostly at third base. The club was 12-34 when he took over; it finished 19-56.

Ferguson moved to second base in 1880, a permanent shift. The Trojans jumped into the first division but still couldn’t manage a winning record. Ferguson, though, built the basis for a winner. He added perhaps the finest rookie crop ever assembled in major-league history: four future Hall of Famers — Mickey Welch, Tim Keefe, Buck Ewing, and Roger Connor. Ferguson had seen Welch, Keefe, and Connor play in the National Association in 1879. Keefe, a fastball pitcher, was pulled from nearby Albany. Third baseman Connor, Welch, and also left fielder Pete Gillespie were brought in from Holyoke. Actually, Ferguson, while with Springfield, had caused a bit of an uproar while opposing Welch. He complained bitterly to the umpire one day that Welch, pitching for Holyoke, was illegally raising his arm above his hip while delivering his famed curveball. The umpire ignored Ferguson and Welch tossed a 1-0 shutout. Defeated yet impressed, Ferguson signed Welch for the National League club at the first opportunity. Catcher Buck Ewing joined Troy in September to complete what would be one of the top battery sets of the 19th century.

On September 16, 1881, Ferguson knocked his only major-league home run, a solo shot off The Only Nolan. At the age of 36, he led the league in games played with 85. Troy folded after the 1882 season and Fergy signed with Philadelphia, an expansion club now known as the Phillies. Many of his star players from Troy ended up with New York. Philadelphia started off poorly and Ferguson was fired with a 4-13 record on May 30. The players rebelled against his strict rule and Blondie Purcell was inserted as field leader. Ferguson remained with the club as the second baseman and, oddly, business manager. It was the only time Ferguson didn’t control on-field matters since he was in his early 20s. The expansion club fared so poorly on the field and at the gate that the National League cut its typical 50-cent admission price in half to try to compete with the crosstown Athletics, the American Association champs that season.

Over the winter of 1883-84, Ferguson worked to establish two new clubs. He looked to insert a Philadelphia franchise in Henry Lucas’s upstart major Union Association. He also worked as manager of the Baltimore Monuments, looking to join a proposed minor Eastern League. By March, it was announced that he wouldn’t take part in either venture. On May 3, 1884, Ferguson signed with New York of the National League but he was soon released. Several former teammates from Troy rebelled upon his signing, fearing his tyrannical methods and worrying that he would soon take over the club, usurping Monte Ward as captain. Fergy was released without appearing in a game for the club.

On May 17 he took over the Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the major American Association 12 games into the season. Ferguson played ten games on the field, at 39 the oldest player in the Association. Ferguson remained with the club through July 14, posting a personal 11-31 managerial record. That was the end of his playing career. In a total of 824 games, including the National Association, he batted .265. He also pitched in 11 contests for a 1-3 record and four complete games. Ferguson worked all of 1885 as a National League umpire. He even played some exhibition games with National League clubs that season.

Ferguson started the 1886 season umpiring in the American Association. He was hired on April 24, causing a bit of a stir because he demanded a salary of $1,500, which was $500 more than any other man in blue got. Ferguson bluntly claimed that he deserved it. He then resigned on May 16 to become manager of the New York Metropolitans of the same league. Ferguson managed the club without much success until May 30, 1887. Again, he was released because of strife with his men, exacerbated by a poor record, 6-24. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat commented, “The charge was owing to the peculiar manner in which Mr. Ferguson managed the club. The men complained bitterly of his habit of sitting on the player’s bench during the games and finding fault with their work.” On Ferguson’s end, he protested against not having full control of personnel decisions, blaming club directors for the team’s poor showing. In 16 years of managing, including the National Association, Ferguson posted a 417-516 record, never rising above third place. (Though by contemporary ruling, Hartford finished second in 1875 and ’76. Total wins at that time, not winning percentage, were the consideration.) On June 13, 1887, he rejoined the American Association umpiring staff, and was “warmly applauded” by the crowd.

Ferguson was considered one of the top umpires of his time, if not the best. Contemporary accounts, from a wide range of sources, laud his efforts in this regard. For example, the Lowell Daily Citizen in June 1879 wrote, “Bob Ferguson is spoken of as the best umpire of the season in Boston.” The Boston Herald from the same timeframe concurred: “Bob Ferguson has umpired all the games played in Boston for the past two weeks, and it is safe to say that a more satisfactory discharge of the arduous duties of an umpire has never been made in the vicinity. His decisions have been prompt, given in a clear voice, and, although he has had several close decisions to give, he has universally been impartial, and thus satisfactory. Come again, Robert, and stay longer.” In July 1886, the Louisville Courier-Journal broadly proclaimed, “Perhaps the greatest and most successful umpire that ever regularly serves was Ferguson…He is a man of iron nerve, strictly honest, and cold and unsociable as an iceberg. He avoided players, who always held him in fear.”

Ferguson’s umpiring philosophy was simple, as he told a New York World reporter in 1887: “The only thing to do is to call things as you see them, and go ahead standing firm by your decisions. … The moment an umpire is driven by the crowd to favor one side or the other, he ought to be called off the field. If a home club or crowd tries to rattle me, it just sets me the other way and they’re apt to catch it.” As can be imagined, he didn’t take any lip as an umpire as well: “Never change a decision, never stop to talk to a player — make ’em play ball and keep their mouths shut and never fear but the people will be on your side and you’ll be called the King of Umpires.”

Ferguson was umpiring as early as 1864, when he was with junior clubs. He umpired in four of the top leagues during the 19th century. He substituted in the National Association every year of its existence (1871-75), and for nine games in the National League in 1879. The National League brought him on board at the end of 1884 and he worked full time through 1885. After leaving managing in early 1887, Ferguson umpired full time in the American Association through 1889. He did the same in the Players League in 1890 and again in the American Association in ’91. He retired for health reasons with over 800 league games on his résumé, more than anyone else. (Some sources claim that Ferguson just didn’t get a call to umpire in 1892 and thus retirement was forced upon him.) In 1890 he became the all-time leader in games umpired, surpassing Kick Kelly. The total was eclipsed three years later. Ferguson attended annual league meetings and became an authority on the rules, advising various league committees. He was an early advocate of pushing the mound back to 60 feet, advising it in 1888.

Ferguson may have been the best of umpires, but that doesn’t mean confrontations and accusations weren’t frequent. In 1887, he made the mistake of wearing eyeglasses while managing. Baseball men latched onto this and made the requisite jokes and accusations. In response, Ferguson just took it in stride: “One day they will give you a ride in a chariot, and the next day they will drive the chariot over you.” A Brooklyn guy, Ferguson was accused of bias toward the Bridegrooms in 1888 and ’89. None other than respected journalist Henry Chadwick swatted down the accusations as baseless. Ferguson came under fire in St. Louis for some unpopular decisions in 1889. The local newspapers, Chris von der Ahe, and Charles Comiskey were particularly critical.

In 1890, Ferguson joined the Players League. It was the first league to utilize two-man umpiring crews on a regular basis. On July 14, he was a participant in the major leagues’ first four-man crew. Due to a scheduling mixup, two two-man crews were posted for the game in Brooklyn that day. Ferguson took home plate in the first inning. The men rotated around the bases each inning after that. The next four-man crew didn’t occur until the 1909 World Series.

Ferguson refused to use a mask while umpiring; he also shunned the use of an indicator. Chadwick, among others, was critical of his stubbornness, as Fergy occasionally forgot the count. Chadwick said, “Bob is very fixed in his ways, far too much in some respects.”

Ferguson saved his money and invested wisely. He was well off by the end of his career. Reports of the day suggest that he was among the richest ballplayers of the time, behind the exceedingly successful sporting goods magnates Al Spalding, Al Reach, and the Wright brothers. A St. Louis Globe-Democrat article in January 1886 said he was worth $40,000 but that seems high. Newspapers carried little information on Ferguson’s life after he retired from the diamond but it is known that he attended games regularly at Eastern Park in Brooklyn until his death.

On May 3, 1894, Bob Ferguson, then 49, was stricken while eating lunch at his home at 687 Greene Avenue in Brooklyn. He collapsed and lost consciousness. He was moved to his bed, where he died at 10:30 p.m., never regaining consciousness. Some reports said he had been ill for some time; others said he was in good health. Sporting Life declared, “The end came to Ferguson suddenly and unexpectedly … although for some months he had suffered from partial paralysis, which he believed had been brought on by excessive smoking.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. This was a catch-all term used to describe sudden death soon after the loss of consciousness. The actual cause of death could have been an aneurysm, stroke, heart failure, or some other malady.

Ferguson was a lifelong bachelor. His estate went to his sister Sarah’s family, the Tassies. The funeral was held at Ferguson’s home on May 7. The Brooklyn Eagle reported, “The parlors were not large enough to accommodate the crowd of people who came. The front stoop was crowded and a few turned away when they found it was impossible to gain admission.” Ferguson was interred at Cypress Hill Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Author’s note

I had concerns during this project that Bob Ferguson’s family wouldn’t be definitively located. After a large chunk of research was completed, nothing was found that could be pointed to for sure. Traditional sources that usually identify family members didn’t in this case. This was concerning in and of itself as other ballplayers’ families are listed if known. There was a possibility from the 1850 and 1860 Censuses which ultimately proved to be him. But this couldn’t be verified and nothing was found at various genealogical sites. Even asking around a bit produced no hits. I’m writing this note just to assure readers that I located the correct family.

My last chance was the Brooklyn Eagle, a source which seemed to hold promise for obvious reasons. There, I stumbled upon a letter to the editor from a few months after Ferguson’s death. It was his sister writing: “I beg leave to contradict a statement made in your paper in regard to my brother, the late Robert Ferguson. He was not a married man at the time of his death, and consequently left no widow or family.” At this point, there was still nothing to definitively point to. She did not give her name and her words were ambiguous as to whether he was ever married or not. I was even concern that it wasn’t the baseball Robert Ferguson she was talking about. The reference she cited was located in the July 7, 1894, issue which declared, “The late Bob Ferguson left his family in easy circumstances. His real estate and life insurance netted the widow about $12,000.” Still, I didn’t know anything for sure.

The savior came in the form of Henry Chadwick, who noticed the exchange and remarked about it in an article, clarifying that “Ferguson was an old bachelor.” That was solved. He was a bachelor and it was the baseball Ferguson under discussion. Chadwick further noted that Ferguson’s sister was named Mrs. Thomas Tasker. Good to know, but that didn’t help — I couldn’t trace that name. Then I recalled a picture from Findagrave.com — the ballplayer’s grave marker. Ferguson’s tombstone includes the names Elsie Pell Tassie and Emma Tassie. I surmised that the names were mixed up — “Tasker” was probably “Tassie.” I quickly found the family of Thomas and Sarah Tassie using Ancestry.com in the 1870, 1880, and 1900 Censuses (Elsie and Emma were Ferguson’s spinster nieces). This was great news because the possibility I had of Ferguson’s family included a mother and a sister named Sarah. I ran further searches of “Tassie” and found Thomas to have a long-time association with the game. Sporting Life even contained his obituary in 1906, which further identified him as the brother-in-law of Bob Ferguson.

With the above information in hand, the family of Hugh and Sarah Ferguson which contained a son named Robert and a daughter named Sarah seemed to be the baseball player’s birth family. But still, Robert and Sarah are common names. The clincher for me was Sarah, the daughter. In the 1850 Census she is listed as “Sarah Johnson” — perhaps Ferguson’s mother was married before. I finally resolved the issue with 100 percent confidence when I found the marriage listing of Thomas Tassie and Sarah Johnson in a November 1860 issue of the Brooklyn Eagle.

Sources

19cbaseball.com.

Ancestry.com.

Arcidiacono, David. “The Hartford Dark Blues.” Hog River Journal, Hogriver.org, Summer 2003.

Baseballchronology.com.

Baseballlibrary.com.

Baseball-reference.com.

Bismarck Daily Tribune (North Dakota), 1888.

Boston Globe, 1886.

Boston Herald, 1879.

Brooklyn Eagle, 1860-94.

Chicago Tribune, 1871, 1877, 1888.

Cleveland Herald, 1870, 1882-84.

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago, 1878, 1887-91.

Devine, Christopher. Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Base Ball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003.

Dunkirk Evening Observer (New York), 1884.

Egan, James M. Jr. Baseball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio, Year by Year and Town by Town 1865-1900. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008.

Fleitz, David L. Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005.

Freyer, John, Mark Rucker, and John Thorn. Peverelly’s National Game: Images of Baseball. New York: Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

Guschov, Stephen D. The Red Stockings of Cincinnati: Base Ball’s First All-professional Team and its Historic 1869 and 1870 Seasons. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998.

Logansport Journal (Indiana), 1894

Louisville Courier-Journal, 1877, 1886.

Lowell Daily Citizen, Massachusetts, 1873, 1879.

Lowell Sun, Massachusetts, 1888.

Melville, Tom. Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 1870-71, 1886, 1891.

Morris, Peter. Baseball Fever: Early Baseball in Michigan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

_____. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, The Game on the Field. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

_____. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, The Game Behind the Scenes. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

_____. Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009.

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball. New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

Nemec, David, and Dave Zeman. The Baseball Rookies Encyclopedia. Dulles, VA: Brassey’s, 2004.

New York Clipper, 1879.

New York Sun, 1870.

New York Times, 1859, 1870-94, 1909.

New York World, 1884, 1887.

Porter, David L. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Retrosheet.org.

Ryczek, William J. When Johnny Came Sliding Home: The Post-Civil War Baseball Boom, 1865-1870. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998.

Ryczek, William J. Baseball’s First Inning: A History of the National Pastime Through the Civil War. North Carolina: Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

Society for American Baseball Research, “Civil War Veterans.”

Spalding, Albert G. America’s National Game. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

Sporting Life, 1885-94.

The Sporting News, 1894.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 1884-87.

Syracuse Herald, 1884-86.

Terry, James L. Long Before the Dodgers: Baseball in Brooklyn, 1855-1884. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002.

Tiemann, Robert L., and Mark Rucker, eds. Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Washington Post, 1884-94.

Wilkes’ Spirit, 1873.

Wikipedia.com.

Wright, Marshall D. The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000.

Full Name

Robert Vavasour Ferguson

Born

January 31, 1845 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

May 3, 1894 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.