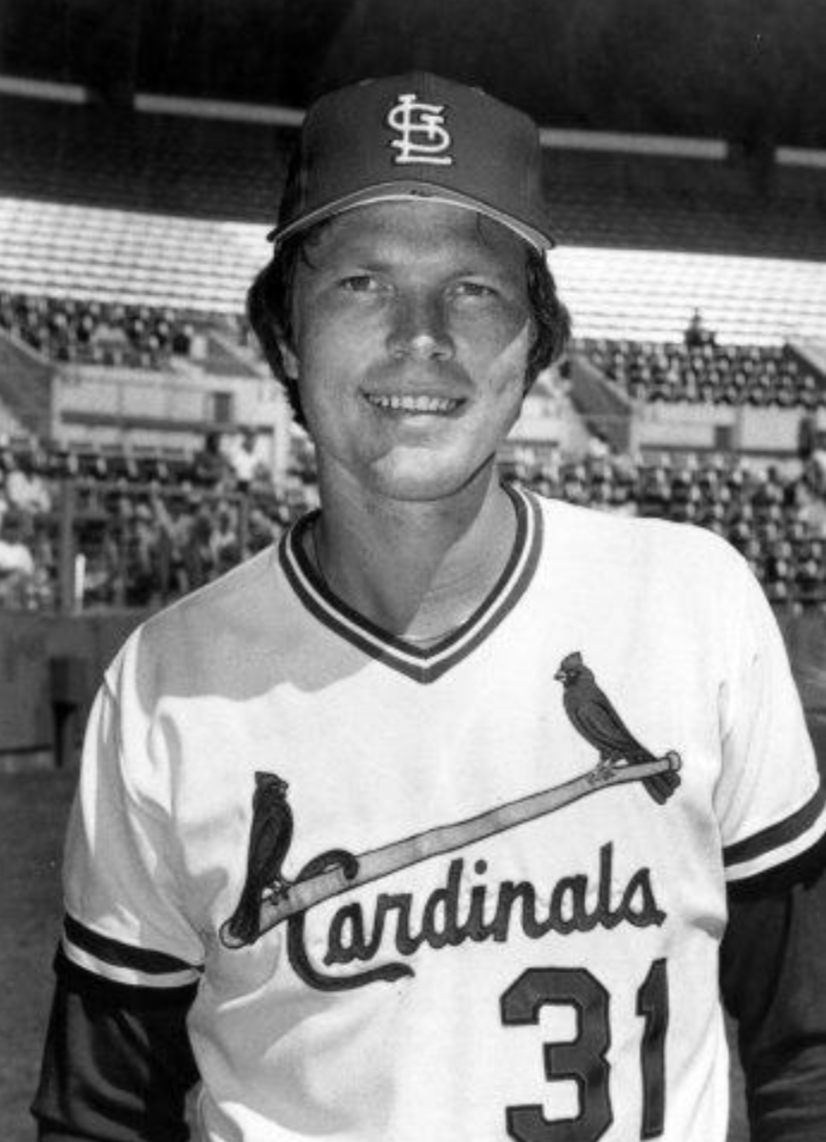

Bob Forsch

On October 28, 2011, the St. Louis Cardinals prepared to play Game Seven of the World Series against the Texas Rangers at Busch Stadium. The organization asked Whitey Herzog, the manager of the last Cardinals team to play a World Series Game Seven at home, to throw the ceremonial first pitch. He had fallen ill, however, and was recovering in the hospital. Bob Forsch filled in for his former manager.

On October 28, 2011, the St. Louis Cardinals prepared to play Game Seven of the World Series against the Texas Rangers at Busch Stadium. The organization asked Whitey Herzog, the manager of the last Cardinals team to play a World Series Game Seven at home, to throw the ceremonial first pitch. He had fallen ill, however, and was recovering in the hospital. Bob Forsch filled in for his former manager.

Forsch pitched major-league baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals from 1974 to September 1988, and for the Houston Astros from September 1988 until his last major-league game, in 1989. Over his career he started 422 games. He won 168 games and lost 136, pitched 19 complete-game shutouts, and posted 3 saves. He compiled a career ERA of 3.76, and a career WHIP of 1.291.

Forsch did not have overpowering velocity. He won 20 games in only one of his 16 seasons in the majors. He was never selected for the All-Star Game. A newspaper article in 1982 described him using such words as “gutty … humble … underrated … self-conscious … analytical … unassuming … .understated.”1 Friends and teammates won’t hesitate to describe him as reliable, witty, and loyal. Cardinals fans, not to mention his family, would be quick to add loved.

That night in 2011, as Bob Forsch walked to the mound and received a round of applause, Cardinals fans saw something they had previously seen only off the mound: Forsch’s characteristic broad, warm smile. “When you’re on the mound,” Forsch wrote, “nobody has a sense of humor. You have to understand: the game’s serious.”2 This time, his smile was unrestrained as he threw the ceremonial pitch, accepted another ovation, and waved goodbye.

Robert Herbert Forsch was born on January 13, 1950, in Sacramento, California, to Herbert and Freda (Roth) Forsch.3 Herb Forsch had played semipro baseball; he “played shortstop and third base, and … pitched, too.”4 Herb, a South Dakotan, and Freda Roth from Alberta, Canada moved to Sacramento after their marriage.5 There, Herb opened Forsch Electric Motors, an agricultural repair shop.6

In the family’s yard, Herb taught his two sons, Bob and Ken, baseball’s fundamentals. In the midst of homework and family dinners, they routinely installed games of “pepper,” during which the Forsch brothers formed a sibling rivalry that was both competitive and (mostly) healthy. Despite growing up in a home so filled with baseball, Bob Forsch attended only one major-league game as a kid: a Giants game against, appropriately, the Cardinals.7

Bob, the younger of the Forsch brothers by 3½ years, was both a talented pitcher and a talented hitter. He made the all-city team8 and led Hiram Johnson High School to a city championship in 1968.9 That year the Houston Astros selected Ken in the 18th round of the amateur draft. 195 selections later, in the 26th round, Bob was selected by the Cardinals.10

Cardinals scout Bill Sayles, himself a former major-league pitcher, believed that Forsch had genuine batting talent, and that his greatest potential was as an infielder.11 Forsch turned down a full scholarship from Oregon State University and joined the Cardinals’ minor-league system as an infielder-outfielder-pitcher.12

On Forsch’s first day in the Cardinals farm system, “He was drowsing in the dugout when an old man with glasses asked him for the count and outs. … [Forsch] looked around a pillar in the dugout and relayed the game info. … Don’t ever let me catch you in here without knowing the count and outs, snapped the old guy. It was George Kissell,” the most famous instructor and respected mentor of the Cardinals farm system.13 (In 2015 Kissell and Forsch were both inducted to the Cardinals Hall of Fame.)

Forsch bounced around the minor leagues for three years and never impressed as a hitter. Ken Forsch, on the other hand, received a September call-up in 1970 and made the Astros roster out of spring training in 1971. That spring, Bob was “playing infield and not doing well.”14

One day, during spring training, Cardinals farm director Bob Kennedy asked Forsch to follow him. Forsch recalled, “We were at our complex in St. Petersburg, and … he took me out to the garage where they kept the tractors that mowed the field[.]” Kennedy pulled open the garage door and went inside. He emerged a few moments later, holding a broom.

“[O]ne of those really big ones with the thick bristles and a handle that’s like five feet long. … He stood the broom on end, with the bristles on the floor, and he held the handle with one hand. Then he started lifting it gradually until he was holding it straight out away from him. … It looks like it should be real easy to do. It’s just a broom, right? … I tried it, and I couldn’t lift it an inch. … Bob just looked at me and said, ‘That’s your problem. You’re not strong enough.’”15

Forsch started over. Maybe Bill Sayles had been wrong. If Forsch couldn’t hit, maybe he could pitch. With the help of the organization’s instructors, especially Bob Kennedy and Bob Milliken, Forsch transformed himself into a professional pitcher. He gradually separated himself from the minor-league pack, throwing two no-hitters along the way. Tom Barnidge later wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Non-hitting third basemen who turn into winning pitchers are about as common as quarterbacks who decide to play defensive end.”16 Forsch, though, did just that.

It was also in 1971, while Forsch was playing at Cedar Rapids, that he struck up a conversation with Mollie Jane Knaau at a local restaurant.17 They married in June of 1972.18

Forsch received his own major-league call-up and started his first game for the Cardinals on July 7, 1974, at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. Facing Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine, Forsch pitched 6⅔ innings, giving up four hits and walking five; he took a 2-1 loss.

Forsch’s next start, and his first game at the Cardinals’ Busch Memorial Stadium (now known commonly as Busch II), came five days later, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Atlanta Braves. He struck out five, walked none, and gave up no runs on four hits—a complete-game shutout. The Cardinals won, 10-0.

Over his next five starts, Forsch posted a no-decision, two losses, and two wins, both of which were complete games. He took a mid-August assignment to the bullpen before returning to the starting rotation on August 31. He was a starter for the rest of the season, posting a 4-1 record, which included another complete-game shutout.

The last start of Forsch’s first season was a high-stakes game for a rookie. With the Cardinals making a September push to claim the National League East from the Pittsburgh Pirates, he started the first game of the team’s final regular-season series against the Montreal Expos. The Cardinals and Pirates were tied for the division lead. Forsch later recalled a brief conversation in the men’s room before the game with Cardinals pitching legend and notoriously fierce competitor Bob Gibson:

“I went in to take a pee before I went out to warm up. Gibson came in and stood at the urinal next to me and asked if I was nervous. … Here was a man who hadn’t talked to me all year, and this is the question I got. … For some reason, I was honest and said yes. Gibby said, ‘Good! I always pitch better when I’m nervous. There’s a difference between being nervous and being scared.’ … And then he left. … I couldn’t believe that he would ever have been nervous. But I thought if Gibson said it, that was good enough for me.”19

Forsch gave up only three hits and one run in a complete game, pitching the Cardinals to a 5-1 win. Gibson, however, lost his start the next day. Once the Pirates then completed a 10-inning comeback win over the Cubs, the Cardinals were eliminated.

In his sophomore season, 1975, Forsch secured his place as a Cardinals starter. He was impressive, posting a record of 15-10, at .600 the team’s best won-lost percentage among starters, and tied for the team’s most wins. He posted an ERA of 2.86, also the best among Cardinals starting pitchers.

In spring training of 1976 Forsch injured his throwing arm.20 He received medical attention, but hid much of the pain and powered through it. “[I]f you don’t pitch, you don’t get paid. At least not the next year, when your one-year contract is up.”21 Forsch was 8-10, and his ERA and WHIP both jumped significantly.

Forsch rebounded in 1977. During a season in which the Cardinals’ owner, August (Gussie) Busch Jr., installed disciplinarian Vern Rapp as manager and the team came close to mutiny,22 Forsch became a 20-game winner with a 3.48 ERA. (He lost seven games.) The Cardinals finished third in the NL East.

April 16, 1978, was not an ideal day for baseball in St. Louis. A cold front had blown in, bringing thunderstorms and persistent fog.23 As a sparse crowd sauntered into Busch II that afternoon, the temperature was under 45 degrees.

The Cardinals had been losing crowd appeal throughout the 1970s — their home opener, six days earlier, drew only 19,241. “The Cardinals’ tradition took a hike in the ’70s. … I kept hearing about the baseball tradition in St. Louis; at the time, I didn’t understand it. We were playing bad baseball, and people weren’t going to pay for it. … I always had fun, though.”24 Only 11,495 showed up to watch Forsch start his third game of the season, against the defending National League East champion Philadelphia Phillies.

In his second start of the season, he had struck out nine Pirates, walked three, and allowed four hits in a complete game. The Cardinals won, 5-1. Forsch’s parents had made the trip from California to see that game, which Forsch described as one of the best he ever pitched; “I really felt proud,” he recalled.25

Against the Phillies, Forsch was at the top of his game, though when he arrived at the ballpark he didn’t feel like it. “My arm just felt weak, like I’d spent it all the game before.”26

Nevertheless, in the fifth inning, Forsch was protecting a 1-0 Cardinals lead. With one out, he walked Richie Hebner — the Phillies’ first baserunner. Hebner put himself in scoring position by stealing second. Although Forsch had struck out no one to that point, he ended the threat by striking out the next two batters.

As the game progressed, none of Forsch’s teammates wanted to talk to him — they were honoring an age-old baseball tradition. When he retreated into the Cardinals’ clubhouse, however, a radio was on and tuned to local station KMOX. “‘They were saying … that no no-hitter had been pitched by a Cardinal in St. Louis in 54 years.’”27

By the top of the eighth inning, the Cardinals led 4-0 and the Phillies had managed only one more baserunner — another base on balls. Leading off the eighth, Garry Maddux hit a hard groundball to Cardinals third baseman Ken Reitz. Reitz “reached for the ball but it went under his glove.”28 “Everybody in the stadium was watching the scoreboard to see whether it was called a hit or an error.”29 Without delay, a number 1 appeared, not under the Phillies’ H column, but under the Cardinals’ E column. The crowd erupted.

“Neal Russo of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch — who was the official scorer — called it an error,” Forsch recalled; “I later asked Neal about it. … He told me, ‘That far along in the game, the first hit has to be a clean hit.’”30 Maddux was eliminated in a 6-4-3 double play. Ted Sizemore then hit a line drive directly to shortstop Garry Templeton, ending the Phillies half of the eighth. Forsch was just three outs away.

Pinch-hitting and leading off the top of the ninth was the Phillies’ Jay Johnstone. Ted Simmons, the Cardinals’ catcher and Forsch’s good friend, said a pivotal pitch that inning was “‘the first pitch to Johnstone. … [I]f he took that pitch for a strike, we had him.’”31 They did, on a groundout to Templeton. Next up was Bake McBride. “‘He hadn’t hit at all during the series. We kept feeding him slow stuff,’” Simmons said.32 McBride grounded out to second base.

Larry Bowa batted for the Phillies with two outs.. He beat the ball into the turf for the fourth time that day, this time to Ken Reitz, who threw for the out at first. Forsch had his no-hitter. After the game he received a congratulatory telegram from the last Cardinal to throw a no-hitter, Bob Gibson. “I thought that was really neat,” Forsch said. “Nobody sends telegrams anymore.”33

A little less than a year later, at the Astrodome in Houston, Ken Forsch celebrated a no-hitter of his own. “I thought of all the great brother acts in baseball,” he said. “The Niekros, the Perrys, and Dizzy and Daffy Dean.”34 He and his brother had now done something none of those others ever did: Bob and Ken Forsch became the first brothers each to throw a major-league no-hitter.

Between celebratory hugs and champagne-soaked interviews, Ken Forsch received a telegram. It read: “Congratulations on your no-hitter. I know how it feels. Enjoy every minute of it. Your Little Brother.”35

Things changed quickly for the Cardinals starting in August of 1980, when Whitey Herzog took over as manager and general manager. Though not the most offensively powerful team, Herzog’s Cardinals were a defensive juggernaut. With a solid infield anchored by the acrobatic future Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith at shortstop, a groundball pitcher like Bob Forsch was perfectly in his element. In fact, of the starting pitchers in St. Louis before Herzog’s arrival, only Forsch was left 18 months later.36

A player strike split the 1981 season. Despite finishing 1981 with the best record in the National League East, the Cardinals were denied a spot in the playoffs by a convoluted playoff format. The shortened season also denied Forsch the ability to play out what statistics suggest could have been one of his best years.

Forsch, Herzog, and the Cardinals waited until 1982 to experience the postseason — the franchise’s first such appearance since 1968. Forsch’s first postseason start came in Game One of the National League playoff against the Atlanta Braves. He pitched one of the games of his life: a complete game in which he allowed no runs, walked no one, and gave up just three hits. The Cardinals won, 7-0. Bob Gibson, then the Braves’ pitching coach, said, “This is the best I’ve ever seen him pitch. … But with guys like Forschy, this is the time of year they pitch like that.”37 The Cardinals swept the Braves in three games to advance to the World Series. Forsch, though, would never pitch so well again in the postseason.

The 1982 World Series was a competition between polar opposites: The St. Louis Cardinals’ speed and defense, and the Milwaukee Brewers’ power. The Cardinals started Forsch in Game One.

By the fifth inning, Forsch had allowed three runs on six hits. He did not have his best stuff, but he was getting by. In the top of the fifth, Forsch gave up a home run to his former teammate Ted Simmons, who had been traded to the Brewers in 1980. Forsch recovered and kept himself in the game until the top of the sixth, when Robin Yount ended his game by hitting a two-out, two-run double. The Brewers scored four more times on three more pitchers, besting the Cardinals, 10-0.

The Cardinals, however, won two of the next three games. Forsch had a chance to give them the Series lead in Game Five.

Forsch was better than in Game One, but struggled nonetheless, allowing runs in four of the seven innings he pitched. He made a wild throw attempting to pick off Robin Yount at second base in the bottom of the first, allowing Yount to take third. He scored on a Ted Simmons groundout.

Yount menaced Forsch again in the bottom of the seventh with a solo home run. The Cardinals’ closer, Bruce Sutter, replaced him in the eighth. The Cardinals lost, 6-4.

With only two games left at most, Forsch had thrown his last pitch of the year. He did have at least one more important role to play in the Cardinals’ 1982 World Series run, though: host.

“Game 5 was on a Sunday afternoon and there was an off day Monday. We were on the flight home and all of a sudden Bruce [Sutter] said, ‘Party at the Forsches’ house!’ … I guess Bruce figured everybody needed to relax. He picked our house because it was the best venue. We had a basement with a full bar.”38

After a sparsely attended optional practice on Monday, the Cardinals tied the Series by routing the Brewers in Game Six, 13-1. Bruce Sutter struck out Gorman Thomas to close out the decisive Game Seven, and Forsch was halfway to a dogpile at the pitcher’s mound before Cardinals’ announcer Jack Buck could shout, “That’s a winner!” It was the happiest moment of Forsch’s career.39

1983, however, was a hangover year for the Cardinals. Forsch, who sued a former agent that year for fraud, experienced control problems.40 On September 26, as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran an article disclosing that Herzog wanted Forsch to work on a knuckleball in the Florida Instructional League, Forsch took the mound against the Montreal Expos.”41

Forsch had yet to allow a baserunner when he faced Expos catcher Gary Carter in the second inning. Forsch later recalled, “You know how some guys just bug you? Gary Carter bugged me … bad!”42 Forsch’s previous start had also been against the Expos, five days earlier, in Montreal.

“You always had to pitch Gary inside so he couldn’t get his arms out and pound the ball … I threw a pitch that … just ran in on him for ball four. … He went down to first base. And on the way he said something like, ‘throw the ball over the plate.’ … I wasn’t feeling great. So I said, ‘The next one you get will hit you.’ … I ended up getting knocked out of that game before he came up again.”43

True to his word, Forsch hit Carter with a fastball. “He went to first base and didn’t say a word.”44 The home-plate umpire warned both benches. Carter went from first base to third when Chris Speier sent a groundball through Ken Oberkfell’s legs — an error. Forsch averted the crisis by striking out shortstop Angel Salazar for the third out.

The Cardinals scored all of their runs in the fifth inning, when Ozzie Smith, Lonnie Smith, and Willie McGee each batted in a run.

Forsch later said, “You don’t even think about a no-hitter until after the sixth inning, when you only have to go through the lineup one more time.”45 That time had come after he retired the Expos in the top of the sixth on a strikeout, a groundout, and a pop fly. Mollie Forsch didn’t remember being nervous during Bob’s 1978 no-hitter until the seventh inning; this time, she admitted, “I started getting nervous in the fifth.”46

Dan Schatzeder replaced Expos starter Steve Rogers on the mound in the bottom of the sixth. He was ejected for hitting the first Cardinals batter he faced, Andy van Slyke. After an argument with the home-plate umpire, Expos manager Bill Virdon was also given an early exit. Expos coach Vern Rapp took over the team’s managerial duties. (Rapp had still been the Cardinals manager when Forsch threw his no-hitter against the Phillies.)

The Expos were still hitless with two outs in the top of the ninth inning. “[E]very time I threw a pitch, there was a crowd reaction.”47 With two outs, Oberkfell, now at third base, found himself in the path of another sharply hit groundball, this one off Manny Trillo’s bat. After the game, Oberkfell said, “I’m glad I didn’t make an error on the last one.”48 When Oberkfell threw out Trillo at first base, Forsch became the 25th major-league pitcher to throw multiple no-hitters.49

Five days later, in his final start of the season, Forsch again pitched well, and improved his record to 10-12. By that evening, he had “definitely … decided not to experiment with the knuckleball in the Florida Instructional League.”50

The epilogue came the following year, on April 21. Forsch recalled, “[T]he first time we played the Expos, George Hendrick came into the clubhouse before the game and said, ‘Hey, Gary Carter wants to talk to you outside on the runway.’ … So I went out there, and to his credit, Gary said, ‘I play hard. Every day.’ … And he did. … I told Gary, ‘I pitch hard. Every day.’ … And I did. … I respected him for coming up and saying that. And we never had a problem after that.”51

“In 1984 the [Cardinals] stopped hitting altogether,” wrote Peter Golenbock,52 and Forsch was treated for nerve problems in his back. Forsch rebounded in 1985, and the Cardinals won 101 games to beat the New York Mets in a tight race for the NL East.

After losing Bruce Sutter to free agency, Whitey Herzog had elected to use a “bullpen by committee.” Herzog made Forsch part of the committee and went to a four-man starting rotation. Forsch was a near-perfect fit as a spot starter and long reliever. By September he found his way back into the rotation.

Forsch started Game Five of the National League Championship Series, against the Los Angeles Dodgers. He allowed two runs on three hits and two walks in 3⅓ innings. He was relieved by Ken Dayley in the top of the fourth. The game, tied 2-2, gained a permanent place in Cardinals history in the bottom of the ninth, when shortstop Ozzie Smith hit a walk-off home run off the Dodgers’ Tom Niedenfuer.

The Cardinals, who trailed the Dodgers 5-4 in the top of the ninth inning of Game Six at Dodger Stadium, went to the World Series on a three-run Jack Clark home run — also hit off Niedenfuer.

The 1985 World Series, against the Kansas City Royals, started promisingly enough for the Cardinals. They won the first two games in Kansas City on strong starts by Danny Cox and John Tudor. Although Royals ace Bret Saberhagen overpowered the Cardinals in Game Three, John Tudor shut out the Royals in Game Four to give the Cardinals a lead of three games to one.

Forsch started Game Five. Whitey Herzog told television broadcaster Tim McCarver, who had caught the first game of Forsch’s major-league career, that he would be satisfied if Forsch got through three or four innings.53 After allowing six of the first 11 Kansas City batters to reach base, Forsch exited after 1⅔. It was not Forsch’s day, nor the Cardinals’. In fact, it proved to be the first of three games that Cardinals fans would rather forget. In the eighth inning of Game Six, the Cardinals took a 1-0 lead, then retired the Royals in short order. Whitey Herzog’s “bullpen by committee,” a categorical success, had not given up a ninth-inning lead during the whole of the 1985 regular season.54

In the bottom of the ninth, Todd Worrell got Royals pinch-hitter Jorge Orta to chop a high pitch into the ground, then covered first base and received Jack Clark’s throw for the out. First-base umpire Don Denkinger awarded the base to Orta anyway. In 2010, MLB Network called it the most controversial call in the history of modern major-league baseball.55 Later, with one out and the bases loaded, former Cardinal Dane Iorg hit a single to right field, scoring two and evening the Series.

Game Six was frustrating for the Cardinals. Game Seven, however, was utterly depressing. Cardinals starter John Tudor exited the game in the third inning, after walking in a run — his third earned. Two more inherited runners scored in the next at-bat.

When Tudor’s replacement, Bill Campbell, was replaced by Jeff Lahti in the fifth inning, the score was 5-0. When Ricky Horton replaced Lahti, it was 9-0. Joaquin Andujar, normally a starter, was next. Notorious for his temper, Andujar erupted at Denkinger. Herzog, too, left the dugout to express his frustration. Manager and pitcher both were ejected, and Forsch took Andujar’s place on the mound.

Bob Costas recalls, “When Bob Forsch took the ball, a sense of professionalism, pride and dignity was restored[.]”56 Forsch induced a fly ball to (finally) end the fifth inning. He calmed the situation further by retiring the Royals in order in the sixth before being replaced by a pinch-hitter in the seventh. “[The World Series] went up in flames. It was tough to take, especially since we should have won Game Six — with or without the bad call by Don Denkinger at first base.”57

Although the 1986 Cardinals were a shell of their 1985 selves, Forsch had a career year. Anchoring the rotation, he started more games (33) and pitched more innings (230) than any other Cardinals pitcher. His WHIP, 1.213, was lower than it had been since the strike-shortened season of 1981.

By 1987, though, Forsch showed signs of wear. He and two other pitchers each won 11 games in ’87 — no Cardinals starter that year won more.58 The team won 95 games anyway, took the top spot in the National League East, and advanced to the NLCS against the San Francisco Giants. When Whitey Herzog constructed his postseason roster, Forsch’s role was that of a reliever.

Recalling his times in the bullpen, “ ‘I think it’s kind of fun,’ [Forsch] said. ‘It’s kind of different. That’s the way I approach it. To me, it’s not downgrading. You know when you come to the ball park that you have a chance to get in the game.’”59

Forsch pitched in Games Two, Three, and Five of the 1987 NLCS. While Game Five was arguably the roughest outing of his postseason career, Forsch’s teammates remember his Game Three performance most. San Francisco’s Jeffrey Leonard was giving fits to the Cardinals pitchers, and flaunting it. He hit a home run in each of the Series’ first three games, and mockingly followed each one by circling the bases slowly with his characteristic “one flap down” trot.

Forsch, who entered Game Three in relief of starter Joe Magrane, faced Leonard in the bottom of the fifth. Magrane recalled, “On the first pitch … [Forsch] knocked him on his ass. … and I thought that changed the entire series right there.”60 More than one of the 1987 Cardinals agree.61 The Cardinals started a comeback the next inning. Being a team player, at least during Forsch’s time, sometimes involved throwing at another player. Bob Forsch was, first and foremost, a team player.

The Cardinals continued their rally and won Game Three, 6-5. The Giants won Games Four and Five before the Cardinals advanced to the World Series by shutting them out in Games Six and Seven.

The 1987 World Series was the first to be played partially indoors. The Cardinals’ opponent, the Minnesota Twins, played their home games in the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome. When Forsch entered Game One in the bottom of the fourth, the bases were loaded with no outs. Catcher Tim Laudner hit Forsch’s second pitch for a single, scoring one. Just as starter Joe Magrane removed his earplugs on the Cardinals bench, the crowd erupted as Forsch allowed the first grand slam during a World Series since 1970. He retired nine of the next 14 batters, giving up two more runs on a Steve Lombardozzi home run, before he was replaced by Rick Horton. The Cardinals lost, 10-1.

They lost the second game in Minnesota, as well, before recovering to win Game Three in St. Louis. Greg Mathews, the Cardinals’ starter in Game Four, had experienced trouble with an upper leg muscle in preceding weeks, but told Forsch before the game that it wasn’t a problem.62 It was. Forsch relieved him in the middle of an at-bat in the fourth inning. After completing a walk, which was charged to Mathews, Forsch struck out the next hitter and ended the Twins’ fourth-inning threat.63

In the bottom of the fourth the Cardinals offense exploded. Because Forsch had entered the game in the previous half-inning, he received credit for the win. After pitching major-league baseball for 13 years, and after appearing in three World Series, Forsch’s record finally included a World Series W.

The Cardinals also won Game Five in St. Louis, giving them a lead of three games to two. They led 5-2 going into the bottom of the fifth inning of Game Six, when the proverbial wheels fell off. By the bottom of the sixth inning, Ricky Horton, who had relieved a frustrated John Tudor in the fifth, was having issues of his own. Forsch entered with a runner on first and no outs. A walk and a passed ball put Minnesota runners on second and third. Forsch, however, bracketed an intentional walk of Don Baylor with a pair of infield popups from Gary Gaetti and Tom Brunansky.

Forsch may just have been able to get out of the jam. Herzog, though, opted to have lefty Ken Dayley pitch to Kent Hrbek, a left-handed hitter. Dayley followed Forsch’s Game One example and gave up the second grand slam of the 1987 World Series. The Cardinals lost Game Six, 11-5.

Things looked promising for the Cardinals in Game Seven, as well, until the Twins tied it in the fifth inning and went ahead in the sixth. They added an insurance run in the eighth before their closer, Jeff Reardon, retired the Cardinals in order in the top of the ninth to lock up the World Series.

On August 28, 1988, Forsch pitched six innings in Cincinnati, giving up six hits, walking five, and allowing three earned runs. When he was relieved in the top of the seventh by Ken Dayley, the Cardinals led the Reds, 5-3. The score had not changed by game’s end, and Forsch recorded his 163rd major-league win. He and the Cardinals then flew to Atlanta to start a three-game series with the Braves.

At about 3:00 p.m. the following day, Forsch got a phone call.

“I was already at the ballpark and in uniform. … I’d rather get to the ballpark. There was always a card game or something going … you know, the fraternity, the roadshow. … And I get called to the phone in the clubhouse. And [Cardinals GM Dal Maxvill] said, ‘We’ve made a trade and you’re going to Houston.’ … Except I told him, ‘Hey, you can’t trade me without my consent.’ … Dal told me, ‘Well, if you stay here you’re not going to pitch again.’”64

Having amassed more than 10 years of major-league service and having spent the last five years with the same club gave Forsch the right, at least technically, to veto any trade arranged by the Cardinals.

“I was a little shocked, to say the least. I told [Whitey Herzog] that I was … thinking of vetoing the trade. … Whitey said, ‘It’s my team. And nobody’s telling me who I’ll pitch and who I won’t pitch.’ … Then I asked Whitey what my [contract] situation would be for the next year, the ’89 season. He said, ‘The same situation that it’s been for the last three years.’ … Which meant I’d have to make the team in spring training.”65

Forsch did not have long to make up his mind. In order to be eligible for the playoffs, he would have to make it onto the Astros roster before August 31.

“[The Astros] said I’d have a guaranteed contract for the next season, 1989. … So I decided to okay the trade. … I wasn’t ready to quit. I wanted to see what another organization was like. … My brother had played in Houston and had liked it down there. And the Astros had a really good team that was going for a championship.”66

On September 5, 1988, Forsch pitched the first game of his major-league career for a team other than the Cardinals. He won the game, giving up five hits, walking one, and allowing no runs through eight innings before Dave Smith closed out the ninth. The Astros, however, did not make the playoffs. After Forsch won his Astros debut, they won only eight of their last 25 games. They finished fifth in the National League West, just two games over .500.

August Busch Jr. died on September 29, 1989. He was succeeded as team president by his son, August Busch III, who made no secret of his dislike for ownership of the Cardinals. The club’s ownership situation would be in a state of flux until 1996.

The Cardinals started the 1990 season poorly. “Whitey [Herzog] wanted certain players [each in the last year of his contract] signed, or in the alternative, traded. With the death of Gussie Busch … Whitey was unable to get the front office to act. Frustrated, he quit.”67 Herzog’s departure, coupled with the death of Gussie Busch, signaled the end of an era for the Cardinals.

As promised, the Houston Astros extended Forsch’s contract through 1989. He spent most of the year as a starter, but his performance declined. The Astros did not offer him another contract extension.

Forsch later explained that the decision to retire was a relatively easy one: “[W]hen I was young and I’d lose … I always thought I’d win the next game, and I always knew when that game would be. … When I reached the end of my career … I didn’t know when I could redeem myself.”68

After retiring, Forsch turned down opportunities to coach with at least two clubs, the Cardinals and the Phillies.69 Once his playing days were over, Forsch loved the time he was able to spend with his family. Whenever he was home during his career, he had always made sure to drive his daughters, Amy and Kristin, to school; “that’s the only time I see them,” he had lamented in 1986.70 He could now give them the time he’d always wanted.

Forsch also spent time fishing and golfing, sometimes for charity, but always preferably with one or more of the many friends he made during his career. Additionally, he enjoyed sitting comfortably at home on his couch.71 “He is so desiring to be at home and with his family that he’s a real tough one to get to do things[,]” his wife once said.72 Doing nothing, Forsch never hesitated to admit, was among his favorite pastimes. “And I’m reaaaaaal good at it.”73 He perennially delayed returning to baseball as a coach, although it never strayed too far from his mind.74

Forsch took up one activity in the fall of 2002 that he had never previously imagined; Bob Wheatley wrote, “He had no plans to do a book. Ever. … ‘Oh no,’ he said, ‘I can’t write a book.’ … ‘You don’t have to,’ I said. ‘You just tell stories.’ … It took some convincing but he agreed to give it a try. … He talked … I wrote and munched through his stash of cashews and peanut M&Ms, as Forschie complained that his meager book royalties wouldn’t cover his snack bill.”75 The book they wrote is called Tales From the St. Louis Cardinals Dugout: A Collection of the Greatest Cardinals Stories Ever Told. No source has been more useful in the writing of this biography.

Success returned to the Cardinals after their sale in 1995 and ’96. Ten years later, they began construction of a new ballpark to succeed Busch II. Shortly after their last game of 2005, with their new home halfway finished across the street, demolition crews brought down the old stadium.

Forsch’s first no-hitter, in 1978, was the first no-hitter ever pitched at Busch II. The stadium’s demolition ensured that Forsch’s second no-hitter, in 1983, had been the last — no one else ever pulled it off, even once.

Forsch became fond of spending time as an instructor in the Cardinals fantasy camp each spring in Jupiter, Florida…76 Florida’s climate, apparently, suited him. His daughters having both left home and graduated from college, Forsch’s marriage of three decades ended while he was writing his book.77 He got a fresh start when he married his second wife, Janice, and moved with her to their new home north of Tampa.78

In 2007, former Cardinals general manager Walt Jocketty offered Forsch a coaching job with the Cincinnati Reds. This time, Forsch said yes.79 He spent the next five years as a pitching coach in the Reds’ minor-league organization.

Forsch was inducted to the Cardinals Hall of Fame on August 15, 2015. At the ceremony, Amy Forsch displayed a very familiar broad, warm smile as she spoke on behalf of her father. “[A]fter my dad retired,” she said, “the thing he missed the most was being part of the team. He loved being part of the team.”80

A little less than four years earlier, at home in Florida, Bob Forsch had collapsed. He died on November 3, 2011, at the age of 61.81 It had been less than a week since he relieved his former manager and threw the ceremonial first pitch before Game Seven of the World Series.

He had watched that game in a suite at the new Busch Stadium, with former teammates Danny Cox and Joe Magrane.82 The Cardinals won, 6-2. “He was happy[,]” Danny Cox said; “He was loving what he was doing.”83 He was probably a little nostalgic, as well, seeing the Cardinals reenact the happiest moment of his career. Surely, as Bob Forsch watched the last game he ever saw, his smile had never been broader or warmer.

This biography appears in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-reference.com and the following:

1982 World Series. Dir. Harry Coyle. Perf. Joe Garagiola, Dick Enberg, and Tony Kubek. NBC Sports; Major League Baseball. 1982.

Baseball. Dir. Ken Burns. PBS. 1994, 2009.

“Fans Speak Out.” Baseball Digest, November/December 2015.

Feldmann, Doug. Gibson’s Last Stand: The Rise, Fall, and Near Misses of the St. Louis Cardinals, 1969-1975 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2011).

Hummel, Rick. “Forsch Locks Self out for Summer.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 5, 1990: 5C.

McDermott, Mark, et al. “History.” 2010. BaseballSacramento.com. August 2 2014. http://baseballsacramento.com/History-All-City_1961-1970.html.

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “Bill Sayles.” Diamond Mines. August 2, 2014. http://scouts.baseballhall.org/scout?s-sabr-id=58bff33a.

Simmons, Ted. Remarks at the 2015 Cardinals Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. St. Louis, August 15.

“Fanfare,” Washington Post, January 23, 1988: B2.

Sutter, Bruce. Remarks at the 2015 Cardinals Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. St. Louis, August 15.

Notes

1 Tom Barnidge, “Forsch’s Pitching Outclassed Reviews,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 8, 1982: 1B.

2 Bob Forsch and Tom Wheatley, Tales From the St. Louis Cardinals Dugout: A Collection of the Greatest Cardinals Stories Ever Told (New York: Sports Publishing, 2006), 168.

3 Forsch and Wheatley, 55, 90.

4 Tom Wheatley, “Forsches Wisely Heeded Pa’s Pitch,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 7, 1987: C1.

5 Bob Broeg, “Forsch’s Maturity Key Factor in Cards’ Title Quest,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 27, 1975: 2C.

6 Nelson Greene, “Ken Forsch”, SABR BioProject.

7 Forsch and Wheatley, 26.

8 Forsch and Wheatley, 52.

9 Joe Davidson, “A Look Back at All D-1 Baseball Champions Since 1968,” Sacramento Bee, May 27, 2009. http://blogs.sacbee.com/preps/archives/2009/05/a-look-at-all-d.html.

10 Forsch wrote, in Tales From the Cardinals Dugout, that he was selected in the 38th round of the draft (Forsch and Wheatley, 52); Baseball Almanac and Baseball-Reference.com, however, both list him as being drafted 594th overall, in the 26th round.

11 Forsch and Wheatley, 27.

12 Ibid.

13 Tom Wheatley, “Forschie” (2013), in Forsch and Wheatley, xii.

14 Forsch and Wheatley, 5.

15 Forsch and Wheatley, 5-6.

16 Tom Barnidge, “Forsch’s Pitching Outclassed Reviews,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 8, 1982: 1B, 4B.

17 Broeg, “Forsch’s Maturity.”

18 Carolyn Olson, “Bob Forsch Makes a Pitch to Stay in St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 17, 1986: 3W.

19 Forsch and Wheatley, 15.

20 Forsch and Wheatley, 144.

21 Ibid.

22 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Spike/Avon Books, 2000), 526.

23 Weather Underground. “Weather History for St. Louis, MO,” wunderground.com.

24 Mike Eisenbath, “Malaise … Cardinals’ Winning Tradition Took a Hike in 1970s,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, August 23, 1992: 3F.

25 Forsch and Wheatley, 132.

26 Ibid.

27 Neal Russo, “Forsch Avoids Jinxes, Gets No-Hitter, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 17, 1978: 1C, 4C.

28 Allen Lewis, “Tainted No-Hitters.” Baseball Digest, February 2002: 60.

29 Forsch and Wheatley, 132.

30 Ibid.

31 Russo, “Forsch Avoids Jinxes, Gets No-Hitter,” 4C.

32 Ibid.

33 Tom Wheatley, “Complete Game: Forsch Enjoys Retirement With No Regrets,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, August 23, 1990: 1D, 3D.

34 “Ken Forsch Makes Little Brother Proud,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1979: 2B.

35 Ibid.

36 Golenbock, 538.

37 Barnidge, “Forsch’s Pitching Outclassed Reviews,” 4B.

38 Forsch and Wheatley, 171-172.

39 “Where Are They Now? Bob Forsch,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 15, 2003: D8.

40 “Forsch Files Fraud Charge against His Former Agent,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, May 6, 1983: 6B.

41 Ibid.

42 Forsch and Wheatley, 76.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Forsch and Wheatley, 132.

46 Hummel, “Forsch Adds Some Taste to an Unpalatable Season,” 6C.

47 Rick Hummel, “Forsch Hurls His 2nd No-Hitter,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, September 27, 1983: 1C, 6C.

48 Hummel, “Forsch Hurls His 2nd No-Hitter,” 6C.

49 Hummel, “Forsch Hurls His 2nd No-Hitter,” 1C.

50 Rick Hummel, “Forsch Hurls Another Gem, 3-2,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 2, 1983: 1F, 6F.

51 Forsch and Wheatley, 76.

52 Golenbock, 552.

53 1985 World Series. Dir. Harry Coyle. Perf. Al Michaels, Jim Palmer, and Tim McCarver. ABC Sports; Major League Baseball.

54 Golenbock, 562.

55 MLB Network Countdown, “The Most Controversial Calls in MLB History,” MLB Network. 2010.

56 Bernie Miklasz, “Bernie Bytes: Remembering Bob Forsch.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 4, 2011. http://stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/bernie-bytes-remembering-bob-forsch/article_94654ad2-06f5-11e1-a395-0019bb30f31a.html.

57 Forsch and Wheatley, 40.

58 Golenbock, 569.

59 Malcolm Moran, “Forsch Was Ready for Call,” New York Times, October 22, 1987.

60 Golenbock, 572.

61 Rick Hummel, “Forsch was ‘Icon in Cards’ History,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 5, 2011. http://stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/cardinal-beat/cardinals-pitcher-forsch-dies-at-age/article_bdfb18cc-06f5-11e1-a7f4-001a4bcf6878.html#ixzz1cku6QvBa.

62 Moran, “Forsch Was Ready for Call.”

63 1987 World Series, Game Four.

64 Forsch and Wheatley, 83.

65 Forsch and Wheatley, 83-84.

66 Forsch and Wheatley, 84.

67 Ibid.

68 Golenbock, 580.

69 Tom Wheatley, “Complete Game: Forsch Enjoys Retirement With No Regrets,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 23, 1990: 1D, 3D.

70 Olson, “Forsch Makes a Pitch to Stay in St. Louis.”

71 Wheatley, “Complete Game: Forsch Enjoys Retirement with No Regrets.”

72 Olson, “Forsch Makes a Pitch to Stay in St. Louis.”

73 Tom Wheatley, “The Cardinal Way” (2013), in Forsch and Wheatley, xiv.

74 Ibid.

75 Wheatley, “Forschie,” xi-xii.

76 “Where Are They Now? Bob Forsch,” D8.

77 Wheatley, “The Cardinal Way,” xiv.

78 Ibid.

79 Ibid.

80 Amy Forsch, remarks at the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. St. Louis, August 15, 2015.

81 Rick Hummel, “Former Cardinals Pitcher Bob Forsch Dies at 61,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch November 5, 2011. STLToday.com. http://stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/cardinal-beat/former-cardinals-pitcher-bob-forsch-dies-at/article_d448e11e-0753-11e1-b253-0019bb30f31a.html.

82 Hummel, “Forsch was ‘Icon in Cards’ History.”

83 Ibid.

Full Name

Robert Herbert Forsch

Born

January 13, 1950 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

Died

November 3, 2011 at Weeki Wachee, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.