Bob Porterfield

Manager Casey Stengel summed up Bob Porterfield’s career with the Yankees: “There was always something wrong — sore arm, sore head, sore back, sore legs.”1

Manager Casey Stengel summed up Bob Porterfield’s career with the Yankees: “There was always something wrong — sore arm, sore head, sore back, sore legs.”1

A pitching Big Three of Vic Raschi, Allie Reynolds, and Ed Lopat powered the Yankee dynasty of the late 1940s and early 1950s, but the club was constantly searching for fourth and fifth starters. The great pinstriped hope of 1948 was right-hander Porterfield, who had rocketed up through the farm system in only two years.

Like many other pitching phenoms, Porterfield saw his career stunted by injuries. It wasn’t just arm trouble, but what the philosopher Lemony Snicket calls “a series of unfortunate events.” Porterfield survived a beaning, line drives that ricocheted off various body parts, and an exploding matchbox.

He showed what might have been in four relatively injury-free seasons, when he was one of the American League’s top pitchers. By then the Yankees had written him off and traded him.

Erwin Coolidge Porterfield was born on August 10, 1924, in Newport, Virginia, the youngest of six children of Jesse Clyde Porterfield and the former Annie Zelpha Porterfield.2 Yes, that was her maiden name; there were a lot of Porterfields in southwestern Virginia. Jesse was a plumber who owned a small farm at the foot of Bald Knob in the Blue Ridge range, near the West Virginia border.

Erwin’s father began calling him “Bob” when he was 6, for reasons unknown. Jesse had been a semipro pitcher, and all four of his sons played ball. Two were pitchers and two were catchers, including Bob. Their father fashioned a ball with rags, yarn, string, and tape, and whittled a bat from a hickory limb. Bob said his older brother Cecil was a better ballplayer, but his sister Reba was the family’s best athlete, a high school star in softball and basketball.

At this point, Porterfield’s life story divides into fact and fantasy. Although he said he was a star pitcher for his Newport High team that won the county championship, his coach told sportswriter William Barry Furlong that Porterfield primarily played infield and pitched in relief. He claimed to have graduated first or second in his high school class, but Furlong said school records showed that he was about an average student.

By Porterfield’s account, he volunteered for the army before Pearl Harbor in 1941 and served in combat with the 82nd Airborne Division. As a paratrooper, he said he made five combat jumps and was wounded in the wrist — fortunately, his left wrist. However, Furlong reported, “Most of Porterfield’s version of his Army service is sustained neither by historical fact nor by Army records.” Furlong found that Porterfield graduated from high school in 1942, then was drafted in 1943 and assigned to the 13th Airborne Division, which was never in combat.3 The official army history of the 13th Division says some of its men were transferred to the 82nd, but that was after Germany surrendered in 1945 and fighting in Europe ceased.4

Porterfield came home in January 1946 and worked with his father on construction jobs. Now grown to 6-foot-1 and about 190 pounds, he joined a semipro baseball team. According to Porterfield, his team challenged the Class D Radford Rockets to a game, and he struck out six of the pros in a row. His performance won him a contract with Radford. He struck out 143 in 105 innings, including a one-hitter with 17 strikeouts, before the Yankees’ Class B farm team in Norfolk bought his contract. At the end of the season he married a local girl, Jean Robinette.

Porterfield blossomed into a top prospect at Norfolk in 1947. A former big leaguer, Garland Braxton, coached him, teaching him a change-up to go with his intimidating fastball. Porterfield’s 208 strikeouts led the league, and his 17-9 record put him on the Yankees’ radar.

Jumping from Class B all the way to Triple A Newark in 1948, he went from prospect to phenom. He pitched three consecutive shutouts and 36 consecutive scoreless innings. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher went to Montreal to check out one of his pitching prospects, but said, “One look at Porterfield and I forgot all about the man I went to see.”5

Yankee manager Bucky Harris, locked in a tight pennant race, wanted to call Porterfield up, but general manager George Weiss thought he needed more seasoning. When New York newspapers began asking, “Where’s Porterfield?” Weiss suspected Harris of planting the stories.

By August the Yankees, Red Sox, Athletics, and Indians were elbowing each other at the top of the standings. At Newark Porterfield was 15-6 with a league-leading 2.17 ERA. Weiss gave in.

Porterfield made his debut in Cleveland on August 8, two days before his 24th birthday. The Yankees and Indians started the day just one-half game behind first-place Philadelphia. After Cleveland won the opener of the Sunday doubleheader, Porterfield held the Indians to one run on two hits through six innings of the second game. He gave up two more singles and the go-ahead run in the seventh; then pinch-hitter Hal Peck smashed a liner off the rookie pitcher’s bare hand, knocking him out of the game. The injury was not serious, but it set the tone for his Yankee career.

Porterfield was inconsistent for the rest of August and September. He appeared to be tiring after working more than 250 innings between Newark and New York. The Yankees had fallen behind by the final day, when they met the Red Sox, who had to win to tie Cleveland for first place. Harris gave Porterfield the ball instead of Vic Raschi, a 19-game winner who had been hit hard in his last two starts. The Yankees staked the rookie to a 2-0 lead, but the Red Sox teed off on him in the third, scoring four times before he was relieved. Boston piled on for a 10-5 victory that lifted them into a one-game playoff with the Indians, who won the pennant. The Yankees finished third, two games back. When Harris was fired, some sportswriters thought the disagreement over Porterfield was part of the reason.

The new manager, Casey Stengel, expected Porterfield to compete for a starting spot in 1949. Before spring training Porterfield cut his feet on broken glass while playing with his son in the backyard. Then he came down with his first sore arm and pitched only 12 times for New York. The next year he failed in another chance at the rotation. On June 9 he was carrying an 8.84 ERA when Detroit’s Paul Calvert beaned him. A broken jaw and a concussion that left him with severe headaches effectively ended his season.

He was back in Triple A at Kansas City in June 1951 when Bucky Harris called. Harris, now managing Washington, was negotiating a trade with the Yankees and had gotten permission to see if Porterfield’s arm was okay. “Please, get me,” Porterfield begged. “Don’t worry about my arm, it’s good, and I’ll pitch it off for you.”6

The Yankees got the left-handed pitcher they wanted, Bob Kuzava, in return for a reported $50,000 plus three pitchers who had flopped in New York: Fred Sanford, Tom Ferrick, and Porterfield. A Washington Post headline sneered, “Nats Pick Up Three Losers From Yankees.”7

The trade sent Porterfield from first place to sixth, but he couldn’t wait to get to Washington. Airline pilots were on strike in Kansas City, so he chartered a plane to Indianapolis, where he could make a connection. (Or so he said.)

Porterfield turned into a different pitcher in his new uniform, and quickly established himself as the Senators’ ace. He finished 1951 at 9-8 with a 3.24 ERA, best on the team. Even then, the injury hex seemed to have followed him. One day he was lighting a cigarette when the matchbox burst into flames, burning his face and singeing his eyebrows.

He added a slider to his repertoire in 1952 and lowered his ERA to 2.72, seventh best in the league. His record was only 13-14 as the Senators were shut out in seven of his starts. He won a 1-0 game by driving in the only run himself. On May 15 he held Detroit scoreless on three hits through eight innings while the Tigers’ Virgil Trucks pitched a no-hitter. Porterfield set down the first two men in the ninth before Vic Wertz’s homer beat him. The next spring Porterfield said, “I want to get rid of my reputation as the American League’s hard-luck pitcher.”8

He made his own luck. After losing his first three starts of 1953, he shut out Chicago on five hits. In his next outing he staggered through a 16-hit complete game and hit a grand slam, the first homer of his career, in a 14-4 win. Five days after that he retired the first 18 Philadelphia batters before Eddie Joost broke up the no-hitter in the seventh. He finished with a one-hit shutout and bashed another home run. He pitched his third shutout against the Browns and then beat the Yankees for his fifth straight complete-game victory.

Porterfield chalked up a league-leading nine shutouts and 24 complete games on his way to a 22-10 record and 3.35 ERA, the highest ever for a pitcher who threw nine shutouts. He spun another one-hitter against Boston in August, allowing only a third-inning single by Jimmy Piersall. The Sporting News named him the AL Pitcher of the Year.

He led in complete games again in 1954 as his ERA inched down to 3.32. He was chosen for his only All-Star team, but his record was just 13-15 because of weak run support.

In his first four years with Washington, Porterfield went 57-47 with a 3.16 ERA, ranking in the league’s top 10 in victories and ERA. His home park was a big help. Griffith Stadium had the league’s deepest outfield, and the Senators had one of the league’s best center fielders, Jim Busby, to run down the pitchers’ mistakes. Despite his reputation as a flamethrower, Porterfield was a below-average strikeout pitcher, but had excellent control. He credited backup catcher Clyde Kluttz for working with him to perfect his change-up.

He became one of the most popular Senators with his own “Official Bob Porterfield Fan Club,” and sang tenor in a quartet with teammates Kluttz, Tom Ferrick, and Irv Noren. He bought a home in West Virginia, so Jean and their three children — Robert Lee, Sandra Jean, and Cynthia Ann — were just a few hours from Washington.

The good times ended in 1955. With Chuck Dressen replacing Harris as manager, the Senators lost 101 games and finished last. Porterfield went down with them. He was hit in the knee by a line drive and pitched only eight times in the second half. His ERA ballooned to 4.45 with a 10-17 record and only eight complete games. He complained that Dressen was too quick to relieve him at the first hint of trouble. Porterfield told club president Calvin Griffith that he wouldn’t pitch for Dressen again.

As part of a youth movement, Griffith traded the 31-year-old Porterfield and 37-year-old first baseman Mickey Vernon with others to Boston for five young Red Sox, none of whom ever amounted to much. Porterfield gushed, “I’m tickled pink.”9 The Red Sox, coming off a fourth-place finish, had pennant hopes. Manager Mike Higgins was counting on Porterfield to rebound.

Instead, Porterfield was Boston’s biggest disappointment as the Sox posted an identical 84-70 record and fourth-place finish in 1956. Several fingers on his pitching hand went numb, and the circulatory problem limited him all season. He missed more time with a sprained ankle. Catcher Sammy White said his control was poor and his fastball was straight. His 3-12 record and 5.14 ERA were the worst of his career as a starter.

Porterfield spent most of 1957 in the bullpen while struggling with arm trouble. In May 1958 the Red Sox sold him on waivers to Pittsburgh. His first appearance for the Pirates looked like a comeback; he spun an 11-inning shutout against Philadelphia. But he was hit hard in his next two starts and was sent to the bullpen. Pittsburgh released him early in 1959. He hooked on with the Cubs for four appearances, then went back to the Pirates. Pittsburgh let him go at the end of the season.

At 35, Porterfield kept pitching in the minors. He stayed close to home with the Senators’ Triple A club at Charleston, West Virginia, in 1960, then joined Triple A Syracuse as a pitcher-coach in 1961. He was fired in June, accused of leading a players’ mutiny against the manager.

Walking away from professional baseball, Porterfield owned a variety store in St. Petersburg, Florida, and coached at Florida Presbyterian College for one year. He moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, where he worked a welder in a Westinghouse plant until he contracted lymphoma in his 50s. He died at 56 on April 28, 1980.

Although evidence shows that Porterfield made up significant parts of his life story, his pitching prowess was real. Yankee Stadium, Griffith Stadium, and Fenway Park are dreams away from Bald Knob in southwestern Virginia. Bob Porterfield climbed the mountain and enjoyed the view from the top, if only for a short while.

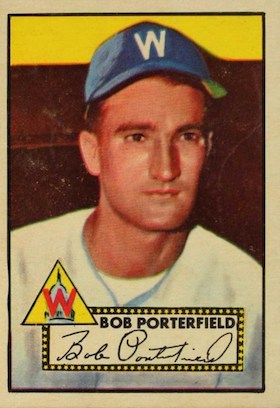

Photo credit

The Topps Company

Notes

1 William Barry Furlong, “The Senators’ Prize Castoff,” Saturday Evening Post, August 14, 1954, 30.

2 Baseball encyclopedias give Porterfield’s birth year as 1923. The Social Security Death Index, his army enlistment record, and his tombstone say 1924, and his Virginia marriage record says he was 22 in September 1946. He was named after President Calvin Coolidge, but his middle name is spelled “Cooledge” in the encyclopedias. He spelled it “Coolidge.”

3 Furlong, 64-65. Porterfield’s enlistment record, available at ancestry.com, shows that he was inducted on May 17, 1943, and classified as a “selectee,” the military’s term for draftee. The National Personnel Records Center told the author that Porterfield’s full service records could not be found. They were most likely destroyed in a 1973 fire that consumed millions of documents at the St. Louis facility.

4 United States Army, “13th Airborne Division” (1946). World War Regimental Histories, Book 180.

http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/180, accessed September 4, 2016.

5 Les Biederman, “Porterfield Earns Title of Hard-Luck Pitcher of Baseball,” Pittsburgh Press, August 30, 1958, in Porterfield’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

6 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, June 19, 1951: 12.

7 “Nats Pick Up Three Losers From Yankees,” Washington Post, June 16, 1951: 13.

8 Murray Olderman, “Jinx Finally Halted Hope of Solons’ Bob Porterfield,” Newspaper Enterprise Association-Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield), June 7, 1953: 19.

9 “Porterfield Elated Over Deal, Vernon’s Feelings Mixed,” Washington Evening Star, November 8, 1955: 42.

Full Name

Erwin Cooledge Porterfield

Born

August 10, 1923 at Newport, VA (USA)

Died

April 28, 1980 at Charlotte, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.