Boom-Boom Beck

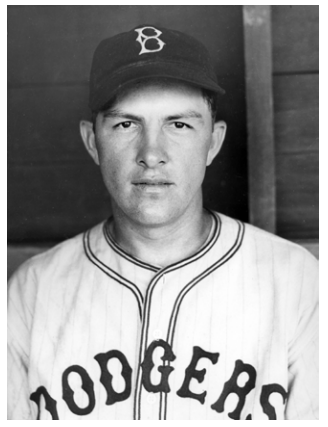

Walter William Beck looked like a pitcher. At least that’s what Casey Stengel thought. “When you see a guy as big and strong and who looks like an athlete, then watch him throw without the slightest suggestion of strain, you just gotta go for him.”1 Beck stood 6-feet-2 and weighed 200 pounds with broad shoulders and a barrel chest. In Memphis, where he pitched from 1930 through 1933, they called him “Big Train” because his stature and his effortless, sweeping side-arm pitching motion reminded fans of the great Walter Johnson. “His fastball is a ‘sneaker’ because he throws it with so little effort.”2 Of course, Beck didn’t have Johnson’s speed. Instead he mixed “a corking fastball, good curve and a change of pace … and he appears to know how to pitch.”3 By the time he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1933, “I learned that I could pitch better ball if I let the rest of the team do part of the work.”4

Walter William Beck looked like a pitcher. At least that’s what Casey Stengel thought. “When you see a guy as big and strong and who looks like an athlete, then watch him throw without the slightest suggestion of strain, you just gotta go for him.”1 Beck stood 6-feet-2 and weighed 200 pounds with broad shoulders and a barrel chest. In Memphis, where he pitched from 1930 through 1933, they called him “Big Train” because his stature and his effortless, sweeping side-arm pitching motion reminded fans of the great Walter Johnson. “His fastball is a ‘sneaker’ because he throws it with so little effort.”2 Of course, Beck didn’t have Johnson’s speed. Instead he mixed “a corking fastball, good curve and a change of pace … and he appears to know how to pitch.”3 By the time he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1933, “I learned that I could pitch better ball if I let the rest of the team do part of the work.”4

Beck grew up in Decatur, Illinois, where his father, an avid baseball fan, worked as a carpenter. Playing on local semipro teams after graduating from high school, Walter eventually caught the eye of a St. Louis Browns scout. In 1924, at the age of 20, he began his professional career with the Browns. However, during three seasons (1924, ’27, ’28), he pitched in only 20 games for St. Louis. Instead, Beck spent most of his time playing for numerous minor-league teams. Finally released by the Browns after the 1928 season, he pitched for three teams the following year. In 1930 he joined the Memphis Chickasaws of the Southern Association. There he became a star, winning 62 games during the next three seasons, including 27 in 1932.

The Dodgers were excited about adding Beck to their 1933 roster. The previous season, Brooklyn had finished third in the National League, nine games behind the pennant-winning Chicago Cubs. While the team hit at a .283 clip, third best in the league, Dodgers moundsmen were among the worst in the league. The once reliable Dazzy Vance had slumped for the second year in a row. By the time the 1933 campaign began, he was sitting in the St. Louis Cardinals bullpen. With the exception of 20-game-winner Watson “Watty” Clark, the rest of the Dodgers staff mirrored Vance’s disappointing performance. As a whole they combined for the second worst earned-run average in the league. Team manager Max Carey left no doubt that in 1933 he intended to rebuild his pitching staff. Walter Beck became an integral part of that plan.

Almost as soon as the Dodgers gathered in Miami for spring training, baseball people began touting Beck’s potential. None was more effusive than Jim Nasium, who wrote in The Sporting News, “(Beck) is the bright and shining hope of this Dodger pitching staff. … He will be one of the pitching finds of the year in the National League.”5 Other writers were impressed by Beck’s talent on the mound but also “his obvious intelligence and poise on and off the field.”6 Acknowledging his homey demeanor and conscientiousness, the writers and his teammates dubbed him “Elmer the Great.”7 It was a nickname he carried throughout the season. Most importantly, “(he) has won the unqualified approval of Manager Max Carey.”8

As early as the third day of spring training the Dodgers manager had slotted his newcomer into the team’s starting rotation. Teaming him up with Ray Benge, whom the Dodgers had acquired from the Philadelphia Phillies over the winter, Clark, and young Van Lingle Mungo, who had been impressive late in the previous season, Carey thought he had his pitching problems solved.

The Dodgers’ season started with a win in Philadelphia. The next day Beck made an impressive National League debut. Supported by seven Dodgers runs, he held the Phillies to seven “measly” hits and a single marker. Only in the fourth inning did the home team mount a threat. Catcher Spud Davis led off with a single. Hal Lee followed with another single and both runners moved up a base when Lefty O’Doul in left field misplayed the ball. With runners on second and third, no one out and the score 1-1, “Beck pitched superbly,” striking out two men and getting the third out on a grounder to escape from the jam.9 Phillies manager Burt Shotton was particularly impressed, commenting, “I’ve seen young sensations come up and blow that ball past the hitter but that kid pitches with his head.”10

Beck’s first win was the beginning of a productive two weeks. Though his team struggled, he continued to impress. In his first four starts he lost only once (a 2-1 squeaker to the Boston Braves), giving up just one earned run per game. Four days later he evened the score masterfully, shutting out the Braves, 1-0, for his fourth victory. The Sporting News exclaimed, “Beck was easily the outstanding member of the pitching staff for the first ten days of the season. … Beck is the best young Brooklyn pitcher unveiled since Dazzy Vance.”11

The weeks that followed were not as successful. Dodgers hitters continued to slump while the pitchers faltered. For Beck, the problems began with a 13-4 drubbing by Dizzy Dean and the St. Louis Cardinals. In his next start, against Cincinnati, he failed to get a single out, giving up five first-inning runs. By the end of May Beck had won only one more game while losing four times and giving up more than 10 earned runs per nine innings during the four-week stretch. Meanwhile, the Dodgers were hitting at a paltry .238 clip and scoring only 3.5 runs per game.

June was no better. Aside from a win against Pittsburgh, Beck’s only complete game in more than a month, he lost four more times while his earned-run average continued to soar. Midway through the month, he hit bottom with an embarrassing 15-4 loss to the cellar-dwelling Phillies in which he gave up six runs in less than two innings.

Everyone agreed that Beck’s problem was his loss of control, particularly control of his fastball, and that “when this freshman side-armer can’t throw to his ‘spots’ he might as well be pitching with his left arm.”12 The source of the problem, however, became a well-explored mystery. Since spring training some had warned about the side-arm “bugaboo.” “Those side arm guys can never throw straight two days in succession,” wrote a Brooklyn Eagle scribe.13 Others suggested that the problems arose because Beck was not getting enough work. A week later, there were complaints that he was getting too much work. In mid-June an unnamed “veteran ball player” observed that Beck “doesn’t work into a sweat before he starts on hot days. … All his best work was done in the chill of April.”14 Beck’s lack of concentration was another proposed source of the problem. Critics began calling him a “two-out pitcher,” citing several games Beck had lost games because he allowed opponents to have big innings after he had retired the first two batters.15

In mid-June, manager Carey decided to experiment with his young pitcher by periodically using him in relief. Twice in 10 days Beck wrapped relief stints around his starts. However, because the Dodgers staff was overworked and “tottering,” especially after the June 16 trade of Watty Clark to the Giants, the experiment lasted for only two weeks. Despite the ongoing struggles, the one thing no one questioned was Beck’s confidence. After an ugly loss to the Reds, Carey assured everyone, “He still thinks he’s good.”16

Beck’s and the Dodgers’ travails continued into July. The young hurler started the month with a complete-game victory over the Cubs, but it proved to be his last win for six weeks. His most discouraging effort came on July 23. After coasting through eight innings, he gave up four ninth-inning runs in an 8-5 loss to the Giants.17 Meanwhile his team briefly sank into the National League cellar before scratching its way back to sixth by the end of the month. Finally, in early August a former Memphis teammate, Joe Hutchinson, observed, “He’s pitching too much underhand. He’s always had more stuff when he throws underhand but his sidearm control is much better and he’s practically unhittable that way.”18 Evidently through the course of the grueling season and responding to tough National League hitters, Beck had inadvertently become more of a submarine-style pitcher than a side-armer. By raising his release point, he regained the control he needed to win. The adjustment worked.

In late July, the Dodgers began a seven-week period in which they played 19 doubleheaders, thus putting additional pressure on an already exhausted pitching staff. Despite the workload, Beck began again to show the talent that had excited Dodgers fans three months earlier. On August 13, employing his rejuvenated side-arm style, he ended his five-game losing streak in an 11-0 romp over the Braves. He went on to win two of his next three games. Though he won only twice more during the rest of the season, “Beck’s record over the six-week stretch is amazing. Somehow he managed to salvage five victories. But in the six defeats, the Dodgers supported him with a total of just four runs.”19 Additionally, during that six-week stretch he gave up just over 2.5 earned runs per game.

Beck’s season ended with another frustrating loss, his 20th of the season, to Boston. His teammates were able to score only a single run while committing four errors that allowed all four Boston runs to score. Despite Beck’s dismal 12-20 won-lost record, manager Max Carey was satisfied with his pitcher’s season. “I think the experience he’s gotten taking a regular turn on the mound this year for us will make him a consistent winner next year,” the manager said.20 Certainly Dodgers fans hoped that Carey’s prediction would become a reality.

Encouraged by Carey’s words, Beck was anxious to continue in 1934 what he had started late in the 1933 season. However, when the 1934 season opened, his manager was gone. After a slew of unpopular trades, tensions with his players, and two years close to the National League cellar, Carey had lost the confidence of both fans and the club’s ownership. Instead they preferred Carey’s colorful coach, Casey Stengel. Immediately the new manager let it be known that his primary challenge was his pitching staff. When assessing his pitchers, Stengel listed Van Lingle Mungo as his ace, but “then his voice starts sputtering weakly, something like a dying phonograph record. Benge, Beck, and (Ownie) Carroll didn’t supply the sort of pitching that lifts a club into the first division.”21 Additionally, Stengel was worried that Beck had lost velocity on his fastball, something that Beck himself acknowledged.

Stengel’s concern grew throughout spring training. To compensate for his loss of velocity and trouble pitching to left-handed hitters, Beck attempted to develop a knuckleball. It did not work. He was regularly pounded by the opposition, and even on the few occasions when he did pitch well, he was smacked around by left-handed hitters. Meanwhile the Dodgers manager focused on a couple of rookies or possible trades that would bring an experienced pitcher to Brooklyn. Just a few days before the season opener, Stengel remained “extremely dissatisfied with the Brooklyn pitching staff.”22 Fortunately for Beck, there remained few alternatives and largely because he had a year under his belt, he was penciled in as the fourth man in the Dodgers rotation.

The season started well for “Elmer the Great.” Though his first start ended in a tie, he held Boston to a single run through seven innings. However, the next six weeks did not go as well. He lost four times, gave up over 12 earned runs per game, and only once did he survive as many as four innings. Assessing Beck in early June, Brooklyn Eagle writer Tommy Holmes lamented: “Beck’s performances have been worse than anybody thought they could be.”23 In early June Beck was demoted to the bullpen. For a month he pitched well in relief. In six appearances he gave up only six runs in 14 innings and seemed to have recaptured some of his former effectiveness. As a reward, Stengel decided to give Beck a start in the second game of a July 4 doubleheader against Philadelphia. It became a fateful decision.

Beck’s first start in more than a month didn’t last long. Facing only eight Phillies, he gave up three hits, walked three and allowed three runs in only two-thirds of an inning. Stengel had seen enough. Anticipating Beck’s reaction, Stengel remained in the dugout and instead instructed his catcher, Al Lopez, to inform Beck that his afternoon was over. Meanwhile, from the dugout Stengel waved in a relief pitcher.24

As expected, Beck was furious. Rather than handing the ball to Lopez “(Beck) threw perhaps the best fast ball he has thrown this season up against the right field fence.”25 The ball hit the tin façade with a thunderous boom. Meanwhile, several feet away, right fielder Hack Wilson was dozing with his back to the field. When he heard the boom off the wall, Wilson instinctively rushed to retrieve the ball, turned and fired a perfect strike to second. The crowd howled at the sequence. Soon after, an amused reporter labeled Beck “Boom Boom” and for the rest of his life Elmer the Great was known as Boom Boom Beck.

A week later Stengel gave Beck a chance for redemption with a start in the second game of a doubleheader against the last-place Cincinnati Reds. This time Beck gave up six runs in two innings. The loss was his sixth of the season and helped swell his earned-run average to just over one run per inning pitched. Soon after, with “a so-called speed ball (that) was going faster fence-wards … than it was going up to the plate,” Beck was sent to Albany in the International League.26 Used as both a starter and in relief, he continued to flounder. In late September Albany returned him to Brooklyn.

By the time Beck pitched again, the Dodgers were locked in sixth place with just four games left in their season. Playing his fourth doubleheader in five days, Stengel decided to start two of his most disappointing pitchers, Beck and Leslie Munns. To their manager’s amazement, both won. In the second game, Beck pitched magnificently, limiting Philadelphia to just four hits and winning 10-1. After the sweep, Stengel reported: “The world is upside down.”27 However, despite the performance, no one was surprised when in early November the Dodgers released Beck. He had ended the season with a 7.42 earned-run average and a 2-6 won-lost record.

Not ready to end his career, Beck joined the Mission Reds in the Pacific Coast League. For the next three years he pitched for the Reds, winning 52 games while losing 61. When the club folded in 1938, Boom Boom moved on to two other Pacific Coast League teams in 1938, the Hollywood Stars and the Seattle Rainiers. He was 7-10 combined with a fat 6.67 earned-run average. For most, such a season would signal a further slide into minor-league obscurity, but not for Boom Boom Beck.28

In 1939 Beck’s Memphis manager, Jimmy “Doc” Prothro, was hired to manage the Philadelphia Phillies. Among the worst teams in major-league history, the Phillies at the time were in the midst of five consecutive 100-loss seasons, finishing each season 50 or more games behind the pennant winners and at least 15 games out of seventh place. From 1939 through the 1942 season, Beck was one of the regulars on the Phillies staff. Initially used as both a starter and a reliever, by 1943, his final year with Philadelphia, he came out of the bullpen exclusively. During those five years, he won 12 games while losing 33.

Beck’s major-league career ended three years later after brief stops in Detroit, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh. After four more years in the minor leagues, his professional playing days ended with the Toledo Mud Hens in 1950. In 1957 he returned to the major leagues as the pitching coach for another bedraggled staff, the Washington Senators, where he remained for three seasons. Like the Phillies during Beck’s playing days, the Senators were considered one of the worst teams in the major leagues, with an equally bad pitching staff. Beck’s last decade in professional baseball was spent as a part-time scout for the Senators and minor-league pitching coach for the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves.

Throughout the last two decades of his life, Beck’s passion for baseball and his gift for gab made him a popular speaker wherever baseball fans gathered. His colorful tales were sprinkled with stories about the many players, both well-known and not, whom he had encountered during his years in the game. In those 20 years he earned a comfortable living from his investments and he became an avid golfer. Neither a hip replacement in 1975 nor three years later the death of his wife of 49 years, Pearl, slowed him down much. Until his death on May 7, 1987, Walter “Boom Boom” Beck remained a local celebrity in his Decatur, Illinois, home, a devoted golfer, and a captivating story-teller.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Notes

1 Tommy Holmes, “Casey Stengle (sic) Another Ready to Go in Big Way for Boy From Decatur,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 1, 1933: 19. “When you see a guy as big and strong and who looks like an athlete, then watch him throw without the slightest suggestion of strain, you just gotta go for him.”

2 Tommy Holmes, “‘Big Injun Me,’ Beck’s First Idea: Wanted to Strike ’Em All Out,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 15, 1933: 22.

3 Jim Nasium, “Brooklyn’s 1933 Hopes Rest on Improved Pitching Staff,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1933: 3. Jim Nasium was the nom de plume of Edgar Forrest Wolfe, a sportswriter and cartoonist based in Philadelphia.

4 Tommy Holmes, “Dodgers’ New Hurler Soon Learned He Wasn’t the Whole Team,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 15, 1933: 22.

5 Jim Nasium, “Brooklyn’s 1933 Hopes.”

6 Thomas Holmes, “Manager of the Dodgers Clings to His Five-Man Starting Idea,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 5, 1933: 36.

7 “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1933: 2.

8 New York Times, March 3, 1933: 20.

9 Stan Baumgartner, “Beck Thwarts Phil Hitters; Frederick Thumps at 1.000 Clip,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1933: 13-14.

10 Harold Parrott, “Beck of the Dodgers Impresses With His Nerve in Pitching to Sluggers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 15, 1933: 10.

11 The Sporting News, April 27, 1933: 3.

12 Harold Parrott, “Juggled Lineup Fails on Attack for Carey After Hurlers Crack,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 5, 1933: 19.

13 Harold Parrott, “Walter’s Wild Spree Predicted by Cards as Dodgers Go Wooly,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 3, 1933: 22.

14 Harold Parrott, “Beck Like a Groundhog, Routed Thrice in the Sun: Clark’s Case Alarming,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 14, 1933: 18.

15 Harold Parrott, “Record Puts Rookie of Carey’s Twirling Staff in Freak Role,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 30, 1933: 21.

16 Harold Parrott, “Blow-Up in Row,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 13, 1933: 12.

17 Harold Parrott, “With Shaute Showing Need for Rest, Carey Must Have Pitchers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 24, 1933:18. The Eagle said reliever Joe Shaute was the losing pitcher, but other sources, including Retrosheet.org and Baseball-reference.com, give Beck the loss.

18 Harold Parrott, “Carey Predicts Beck Will Be Consistent Winner on Mound in 1934,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 30, 1933: 18.

19 Harold Parrott, “Shut Out Ball Beck’s Best Effort; Defeat His Lot,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 30, 1933: 10.

20 Harold Parrott, “Carey Predicts.”

21 Tommy Holmes, “It Will Be Do or Die for Dear Old Casey,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1934: 1.22 Tommy Holmes, “Dodgers May Offer Braves Cuccinello,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1934: 1.

23 Tommy Holmes, “Boston Uses Brooklyn as Stepladder to Gain Higher Standing Rung,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 3, 1934: D1.

24 Rex Spires, “ ‘Boom Boom’ Beck Had a Gift of Gab,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald and Review, August 2, 1987: 50. This was a story Beck told many times after he retired. However, in his accounts he made it to the second inning before being lifted for a relief pitcher. The Philadelphia Inquirer box score credits him with only two-thirds of an inning.

25 Thomas Holmes, “Dodgers Win, Then Slaughtered,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 5, 1934: 13.

26 The Sporting News, August 9, 1934: 8.

27 Tommy Holmes, “World’s Upside Down, Says Shocked Stengel as Munns, Beck Win,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 25, 1934: 18.

28 Forrest R. Kyle, “Reserve Clause? Old-Timers Wanted Only a Chance to Play,” Decatur Review, January 23, 1970: 13. Of his time in the Pacific Coast League, Beck later claimed: “I sent DiMaggio and Williams to the majors.”

Full Name

Walter William Beck

Born

October 16, 1904 at Decatur, IL (USA)

Died

May 7, 1987 at Champaign, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.