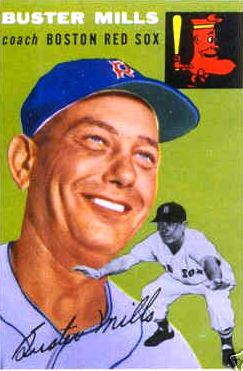

Buster Mills

Born as Colonel Buster Mills, this outfielder-turned-soldier during World War II got a little extra kick out of going up to ranking officers and introducing himself as Colonel Mills.

His father was Elvis, a merchant who owned a general store in Ranger, Texas, about 65 miles east of Abilene in the west central part of the state. Elvis was born of parents from Tennessee. Buster’s mother, Lucy, was from Arkansas, born of parents from Mississippi. Elvis and Lucy started off giving familiar names to their children. Their first-born was named Charles and the second was William. Then they had a daughter and named her Merkel. And when their fourth child was born, on September 16, 1908, they gave him the first name of Colonel and the middle name of Buster. Whether they had other children later on is not known. Buster described himself in his Hall of Fame questionnaire as “Scotch, Irish, Dutch, English, and Indian.” He got his unusual first name because his father’s best friend was an Army colonel – or because of a great-uncle who was a colonel during the Civil War, as he himself wrote in a letter to J. Roy Stockton of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.1 He often went by the nickname Bus.

The 5-foot-11½-inch, 195-pound right-hander, who spent the first half of the 1934 season with the Cardinals, was a football star at the University of Oklahoma, named all-Big Six quarterback in 1930. He capped off the year playing right halfback and scoring all the points by kicking a field goal in the last four minutes of play for a 3-0 final before 60,000 fans in the sixth annual Shrine Game, the East-West All-Star Game. Listening to his son on the radio at home in Ranger, Elvis Mills leapt up and in his excitement kicked a vase and fractured his foot. The Chicago Tribune was more restrained but placed a headline reading, “Mills in Hero Role” above its box score and game story.2 Mills lettered in football, basketball, track, and baseball. In the spring of 1931, while he was playing baseball, the track coach beckoned him over from an adjacent field. Asked to throw the javelin to see if he could help the track team, he did – for 180 feet, enough to give Oklahoma sufficient points to win its track meet. Then, presumably still wearing his baseball uniform, he returned to the ballgame.3

Mills could have tried to pursue a career in football. His father was on the board of trustees of the Ranger school system and hired Blair Cherry as coach for the team. It was under Cherry – now honored by the Texas Sports Hall of Fame for his work coaching Texas Longhorn football – that Bus played halfback and went to the state interscholastic finals.4

But it was in baseball that Buster pursued a pro career, one that had an unusual twist. St. Louis Cardinals scout Charley Barrett saw him playing center field in a game between Oklahoma and Washington University in St. Louis. He hit for the cycle and more, banging out a single, two doubles, a triple, and a home run.

The saying goes that you can’t tell the players without a scorecard, and there were no printed scorecards for the game. When Barrett asked one of the players for the hitter’s name, he didn’t get the most knowledgeable student and was told it was Wahl – there was a Tilford Wahl on the team, who also had the nickname Bus. Barrett had to rush off to cover another event, but sent a message to a colleague in Oklahoma and asked him to sign Wahl to a Cardinals contract. Wahl was perhaps a bit surprised, but signed on the dotted line.

In the meantime, Cleveland signed the other “Bus” – Buster Mills – and sent him to Decatur (Three-I League) and then to New Orleans (Southern Association), which quickly swapped him to Mobile of the Southeastern League, a Cardinals farm club.5 Mills wound up playing with three teams: 32 games with Class B Mobile (he batted .367); 109 games with the Elmira Red Wings in the Class B New York-Penn League (his .337 mark was second in the league); and, to finish his year, with the Rochester Red Wings in the Double-A International League. He hit .360 with one home run in the 15 games he played for Rochester. The January 5, 1933, Sporting News looked ahead to the season to come for Rochester and pronounced, “Mills, because of his showing at the end of last year, won himself the right to have the outfield built around him. He is a certainty to land a regular job and what’s more, predictions are made that he will advance at the end of the season.”

Rochester manager Specs Toporcer had already conceded Mills the center-field job before spring training got under way; another look back at 1932 called him “sensational” and said, “He showed fighting spirit and defensive skill.”6

With the proper Bus under contract, the Cardinals were pleased to see him bat .309 in 405 at-bats for Rochester in 1933; “Colonel Fence Buster” hit 7 home runs, 28 doubles, and 8 triples. He led the league in getting hit by pitches, with 15. By the end of the year, St. Louis had already determined he’d be with the big-league team in the spring of 1934. Team VP Branch Rickey enthused over three recruits for his outfield: Gene Moore, Jack Rothrock, and Mills. “If somebody said to me, ‘Go out and buy the three best outfielders you can buy,’ these three would have been among the first four that I would have considered,” he told the Associated Press.7

Mills made his Cardinals debut in the second game of the year, on April 18, 1934, against the Pittsburgh Pirates. (The 18th was also the debut date for pitcher Paul Dean, younger brother of Dizzy Dean. Diz had started and won the Opening Day game, 7-1. Paul didn’t fare as well, giving up a couple of home runs early on and making it through only two innings. In the fifth inning Mills batted for Bill Walker, the second pitcher of the game. He was retired uneventfully.

It wasn’t a good start for St. Louis, which won the Opening Day game but then lost five in a row. The AP said that when manager Frankie Frisch stuck Mills in the lineup on April 26, it was to try to “shake the jinx” – Mills made an out his first time up, but then hit two singles, a double, and a triple in his final four at-bats. On the 27th Mills hit three singles his first three times up before finally being retired. Two days later he hit his first major-league homer, off Pat Malone of the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field.

It was a very nice start, but by July 5 Mills, batting .236, was released back to Rochester. He had time to get into 63 games, but hit a disappointing .269 and Red Wings fans were also down when Toronto beat Rochester in the playoffs. Nonetheless, the October 4 Sporting News predicted that Mills might be one of the three players most likely to be selected by another major-league club in that fall’s player draft. He was not, and played a fairly full season with Rochester in 1935, hitting .313 in 549 at-bats, with eight homers.

The Red Wings didn’t even make the first division in 1935, and both Gene Moore and Mills were sent to the Brooklyn Dodgers for two unnamed players and cash. Given a shot with Brooklyn in September, the “fast, sturdy right-handed hitter” pounded the first pitch he saw for a double in his debut, drove in a run, and was one of four cited for some “brilliant fielding” in a game game against the Cubs on September 13. The next day he hit a three-run homer off Charlie Root, also at Wrigley. Still, Bus ended the year with a .214 average over the 56 at-bats that constituted his year as a Dodger. It hadn’t taken long for opposing pitchers to realize that he could be fooled with the curveball. They had him “swinging for low curves outside and the rangy young Texan went fishing with a vengeance.”8

It was Mills’s speed that caught a lot of eyes, along with the hope that he could discipline himself at the plate. A couple of impromptu races saw him beat Bill Werber both times, and Werber was highly regarded for his speed.

Mills didn’t make the Dodgers in 1936. It would have cost the team $10,000 to keep him, but Rochester said it was glad to have him back, and that it believed it could sell him for $25,000 by the fall.9 Mills spent 1936 with Rochester once again, hitting .331 with 18 home runs and a league-leading 134 runs batted in. The Cubs scouted him and the Yankees made an offer during the latter part of the campaign, but the Red Wings didn’t want to give him up while still competing. In November the Boston Red Sox sent a “bundle of cash” and, later, infielder Dib Williams to Rochester to complete their purchase of Mills for 1937.10

The Red Sox had added both Mills and Fabian Gaffke to their outfield crew, and both were expected to contend with Dom Dallessandro to see who would join Doc Cramer in the Boston outfield in 1937. It was considered to be a “comeback” year for Buster, and he came back all right – with the best year of his career, playing a full major-league season for the Red Sox and batting .295 in 505 at-bats, driving in 58 runs and scoring 85. He hit seven homers.

Breaking in on the same April 20 date as two other Red Sox, second baseman Bobby Doerr and third baseman Mike “Pinky” Higgins, Mills played right field and was 2-for-4 with a triple as Boston beat Philadelphia, 11-5. It wasn’t all clear sailing, though. With the bases loaded and two outs in the first inning on August 14 in Washington, Mills camped under an “ordinary fly” – and dropped it. Three runs scored and the Red Sox never recovered in that game.11

Mills was named to The Sporting News All-Star team as the best rookie left fielder in the majors. Though he did have his best year, the Red Sox sought improvement with Joe Vosmik, who’d had an even better one. On December 2, Mills, pitcher Bobo Newsom, and infielder Red Kress – and, in a separate deal, coach Oscar Melillo – were traded to the St. Louis Browns to secure Vosmik. New York sportswriter Dan Daniel said that the Red Sox “salted their tender with $35,000 in addition.”12 They’d been trying to land Vosmik for two years, and now felt they would have (with Vosmik, Cramer, and Ben Chapman) their best outfield since the days of Duffy Lewis, Tris Speaker, and Harry Hooper.

The Browns would be Mills’s fourth major-league team. Sportswriter Paul Shannon declared that he “has a world of speed and is a pretty fair batsman, but does not rank so highly as a ball hawk. Yet he has youth and ambition on his side and [Browns manager] Gabby Street may develop him into a star.”13 Newsom and Kress were the keys to the trade, though, and for the two of them, and Melillo, it was a return home to a club where they’d all previously worked.

Mills had a very good 1938 for his second St. Louis team. Though laid up for a while with a sprained ankle suffered on Opening Day, he still appeared in 123 games, earned 466 at-bats, drove in 46 runs and scored 66, while batting .285. In late October, the Yankees traded outfielder Myril Hoag and catcher Joe Glenn to the Browns for pitcher Oral Hildebrand and Mills. It was Hildebrand they wanted and in early January 1939, New York assigned Mills to its Double-A Newark Bears farm team.

Mills turned 31 years old by the end of the season, spent entirely in Newark. He hit .305 in 149 games but got his photograph in the newspapers for another reason. A New York Daily News photo showed him wearing a “safety cap” which, the caption in the August 3 Sporting News said, “fits snugly over the regular uniform cap … made of hard fiber with sponge-rubber knobs to protect the temples.” The caps became optional protective gear in the International League and Mills was reportedly the first to wear one.

Mills began 1940 with Newark as well, but with outfielders Jake Powell and Joe DiMaggio both disabled, the Yankees brought him up on May 3. He was hitting only .222 at the time, but the Yankees needed him. Washington Post sports editor Shirley Povich was unkind, decrying the paucity of talent in the Yankees farm system and writing, “When they needed an outfielder a couple of months ago, the best man they could bring up was Buster Mills, a two-time failure in the majors.”14 It was one of several disparaging references to Mills by Povich. Two days earlier, he’d written that Mills had been sent from Boston to the Browns and from there to the minors “because he couldn’t hit. Mills is wearing a Yankee uniform, but he doesn’t strike the enemy pitchers as a proverbial Yankee, if we are not being too subtle.”

When he did hit for the Yankees, he hit well, batting .397 for the season – but in just 63 at-bats. When the Yankees tried to send him back to Newark, three clubs put in waiver claims. Bus spent most of 1940 not playing at all, though after the Yankees farmed him back out to Kansas City of the American Association on August 15, he hit .348 in 132 at-bats for the Blues. Then Mills hit .307 for the Blues in 1941, with 63 RBIs.

The Cleveland Indians took another crack at Buster in early April 1942, taking him in trade for outfielder Larry Rosenthal and some money. They’d seen his play against them in spring training and were impressed, and planned to have him play outfield in place of Gee Walker, who had been sold to Cincinnati. Mills wasn’t quite as impressive over the next couple of weeks and was slated for a backup role and platooning against left-handers – though in his first crack, on April 18, he singled three times, one of which helped beat the White Sox, 1-0. He drove in half the runs in a 6-1 win against the Athletics on the last day of April, including the game-winner. As seemed to often be the case, Mills started off exceptionally well (10-for-18 for the Tribe through early May), but then softened. Three singles, a triple, four RBIs, and a steal of home helped him do in Washington, 7-1, on July 26. Not swinging the bat at all helped him win the September 17 game; he walked to plate the winning run in the bottom of the 11th inning against the Senators. For the season, Mills hit .277 in 195 at-bats.

Except for military service, Mills stayed in the Indians system throughout the World War II years. He joined the Army Air Force in mid-November of 1942, departing the Indians on the same day as Bob Lemon. Mills was initially stationed in Waco, Texas, recruited there by Birdie Tebbetts, who pulled together quite a group of ballplayers –Hoot Evers, Sid Hudson, and more. Hank Greenberg became the assistant director of physical training at Waco. Mills was commissioned a second lieutenant in April 1943 – but still had a little fun since now he had officially become Lieutenant Colonel Buster Mills.

Oddly enough, another baseball playing Buster Mills made his appearance around this time, a catcher for Holy Cross. His name was William H. Mills, and had been given the nickname Buster with Colonel Buster Mills in mind. This Mills, who went by Bill, played in five games for the Athletics in 1944.

Baseball, by the way, had another ballplayer who could honestly introduce himself as an officer, at least in name: Major Kerby Farrell.

Our man Mills was transferred to the Aloe Army Air Field in Victoria, Texas, in July 1944, but not before he helped the Waco Wolves win their 14th game in a row with a tenth-inning homer against a semipro team from Dallas. He did continue to play some for Waco, though Tebbetts had to give up a gold case that Mills had been eyeing in order to land him for the semipro tournament.15

In 1945, now a first lieutenant, Mills was sent to Hawaii, where he managed the 73rd Wing Bombers in a series of exhibition games for the troops in the Marianas. Buster’s Bombers beat Birdie Tebbetts’ 58th Wing team, 4-3, on Tinian on July 27, with Ferris Fain’s home run in the bottom of the ninth making the difference. Tex Hughson was Buster’s starter. The Bombers beat the 313th Flyers the next day, 5-4.

Buster’s Bombers beat Birdie’s crew in the Tinian series, but both Mills and Tebbetts were on the American League all-star team when it came to playing a Pacific all-stars series on Iwo Jima. On August 26 the Americans beat the Nationals on Tinian, 3-2, but lost to the Nationals at Higashi Field on Iwo Jima, 5-1, on September 2. Mills played left field in that game and was 0-for-4.

There was at the same time an ongoing round-robin series on Iwo Jima. Mills’ Bombers had won nine of 11 games in the Marianas series, and took the first game on Iwo Jima as the 73rd Bombers beat the 313th Flyers on August 29, 3-2. Joe Gordon’s three-run homer for Tebbetts’ 58th Wingmen helped beat the Flyers in the second game, 5-4, on August 30. The Flyers came back to tie it, but Enos Slaughter’s seventh-inning homer won it for the 58th and reliever Rugger Ardizoia bore the defeat. Tebbetts’ team won the series when 23-year-old White Sox rookie Nick Popovich shut out Mills’ Bombers on three singles, 3-0, in the August 31 final game.

After being mustered out of the service and coming off the National Defense List in February 1946, Mills joined those competing for a slot with the Indians. Early in spring training, manager Lou Boudreau announced that Mills would be hired as first-base coach but kept on the active roster so that he could be used as a pinch-hitter as occasions arose.16 Melillo became the third-base coach.

Mills appeared in nine games in 1946, until he was formally released from the active list on July 3, and he coached full time all season for Cleveland. There was one downside to the job that year; the Indians – now under Bill Veeck’s leadership – typically had baseball comedian Max Patkin “coach” road games for the first inning or two. Mills had the unenviable job of replacing Patkin in the box as the game got under way. Fans immediately noticed the change and would shout at Mills, “What are you doing out there? Go into your act, you dope. We want Patkin.”17 When the Browns picked Cleveland baserunner Ray Mack off first while Patkin was doing his jitterbugging, Boudreau called a halt to the levity.

After the season Mills joined a touring group of American League all-stars put together by Paul Richards, then catching for Detroit. His grand slam helped win a 10-2 game against the Sherman club of the East Texas League. The Indians offered to give Mills a job managing in the minors, but he took his time to look around for a position that would keep him “in the Big Time” and by December was offered a job coaching with the White Sox under manager Ted Lyons.

In his second career as a coach, Mills coached for the White Sox from 1947 to 1950 under Lyons, Paul Richards, and Jack Onslow. Onslow let Mills go after the 1950 season because of his “conservatism in sending runners home.”18

The day he was officially released, Mills was managing in a night game in Memphis. Just as he had in leading the 73rd Wing Bombers in the war, Mills led a tour of barnstorming all-stars after the season. A 33-game schedule running from October 10 in Montreal to November 5, with a day game in Oakland and a night game in San Francisco, kept him busy as the “American League” manager. Players including Early Wynn, Jerry Coleman, Mike Garcia, Al Rosen, and others toured, with Duke Snider, Red Schoendienst, Alvin Dark, Gil Hodges, Ralph Kiner, Sam Jethroe, and others on the NL team.

In January 1951 Mills was hired to skipper the Superior Blues of the Northern League. The Wisconsin team was one with which the White Sox had a working agreement. The Blues came in third. In the playoffs, it was Eau Claire and Superior with one win apiece when five games in a row were called off because of rain, and Superior canceled the series. Eau Claire won by default but lost the best-of-three finals in two games to Grand Forks. Early in the season, Mills had been ejected from a game for allegedly pushing umpire Don Spillman. While sitting out the game, he reportedly came up with the idea of managing from his car via walkie-talkie while a player on the bench filled him in on what was happening. The league president shot down the idea.19

It’s not clear what Mills did during the 1952 season, but in October he was hired as a coach for the Cincinnati Reds, under manager Rogers Hornsby. Near the end of the 1953 season, Hornsby quit the sixth-place team with eight games remaining. Mills became acting manager, but the team made it clear that it would not be considering him for the position on a permanent basis and was looking for an experienced skipper for the year to come. The team played 4-4 under Mills.

Two days after Cincinnati’s season ended, Mills was hired by the Boston Red Sox to coach under manager Lou Boudreau in 1954. Before reporting to Sarasota for Red Sox spring training, he went to Venezuela. Cincinnati had asked him to manage the Pastora club in the Venezuelan league, with which the Reds had placed some players. The team was based at Maracaibo, and won the league by a 7½-game margin with a record of 48-30. He was asked to return to the post for another winter in 1959, but had to decline for unspecified personal reasons.

When Pinky Higgins was named to skipper the Red Sox for 1955, he dropped Mills, “blamed for several bad decisions” in handling third-base traffic, according to the Hartford Courant.20 The respected Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor agreed with the common perception: “Important runs were constantly eliminated because of Buster’s judgment. Catchers would be waiting with the ball when green-lighted Bostonians raced innocently homeward.”21

Mills maintained a residence in Waco and for a number of summers starting in 1955 helped coach at the Big State Boys Baseball Summer Camp, with Sid Hudson, Monty Stratton, and Joe Moore among the other staff.

Buster took up scouting for Kansas City, and was a determined one – actually signing one prospect on Christmas Day itself, in Abilene. But he was part of a revolt in September 1961. After owner Charlie Finley had fired farm director Hank Peters, manager Joe Gordon, and GM Frank Lane, the director of player personnel (George Selkirk) also quit, and then so did a group of six scouts, one of whom was Mills. Within a month, he was snapped up and signed to scout for the Yankees.

Mills died on December 1, 1991, at Arlington, Texas, and was buried in Waco. He had lived in Ranger, Texas, much of his life, moving to Waco for a short time and then Arlington. He had been a member of First Methodist Church of Ranger, on the board of directors of Ranger Savings and Loan, a member of Masonic Lodge in Ranger, and a member of the American Legion. Survivors at the time of his death included his wife, Madge Mills of Arlington; and a sister, Myrtle Watson of Grants Pass, Oregon.

Sources

All consulted sources are mentioned in the text. Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org were the sources for baseball statistics.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, January 18, 1934.

2 Chicago Tribune, December 28, 1930. The vase kicking was told by sportswriter Shirley Povich, among others. See the April 1, 1937, Washington Post.

3 The Sporting News, November 7, 1935.

4 Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1948.

5 The Sporting News, May 11, 1933, and January 18, 1934.

6 The Sporting News, March 9, 1933.

7 Hartford Courant, November 27, 1933.

8 The Sporting News, September 19 and 26, 1935.

9 Hartford Courant, May 3, 1936.

10 The Sporting News, December 3, 1936.

11 Washington Post, August 15, 1937.

12 The Sporting News, December 9, 1937.

13 The Sporting News, December 9, 1937.

14 Washington Post, May 24, 1940.

15 Christian Science Monitor, October 17, 1944.

16 The Sporting News, March 21, 1946.

17 The Sporting News, September 11, 1946.

18 The Sporting News, April 19, 1950.

19 The Sporting News, June 13, 1951.

20 October 14, 1954. See also The Sporting News, October 27, 1954.

21 Christian Science Monitor, September 13, 1955.

Full Name

Colonel Buster Mills

Born

September 16, 1908 at Ranger, TX (USA)

Died

December 1, 1991 at Arlington, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.