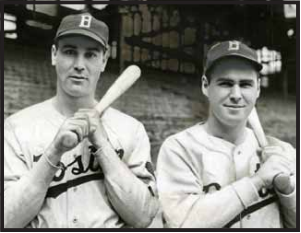

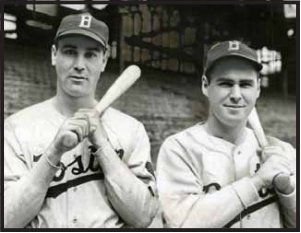

Butch Nieman

Butch Nieman had a short but productive major-league career. Considered a replacement player during World War II, Nieman patrolled the Boston Braves outfield on a regular basis from 1943 to 1945 and can best be described as a streak hitter with a penchant for delivering the big hit in the clutch. In his three-year stint he finished in the league’s top 10 in triples in 1943, and in home runs and at-bats per home run in 1944. Nieman’s career totals include 332 games played, 269 hits, 37 home runs, 167 RBIs, and a .256 batting average. One of the best examples of his ability to dominate the game was a week in August 1943. “Butch Nieman may never be known as one of the major leagues’ outstanding performers but right now he is providing the finest clutch hitting in baseball,” wrote Judson Bailey of the Associated Press. “In the last week he personally has decided four important games for the Braves. On Friday he hit a two-run homer in the tenth inning to beat the Cubs 5-4. Last Saturday Nieman hit his second home run of the season in the ninth inning to beat Brooklyn and on Sunday he smashed a ninth-inning double to down the Dodgers a second time. In the same week he also hit a triple in the 12th inning whipping the Cubs.”1

Butch Nieman had a short but productive major-league career. Considered a replacement player during World War II, Nieman patrolled the Boston Braves outfield on a regular basis from 1943 to 1945 and can best be described as a streak hitter with a penchant for delivering the big hit in the clutch. In his three-year stint he finished in the league’s top 10 in triples in 1943, and in home runs and at-bats per home run in 1944. Nieman’s career totals include 332 games played, 269 hits, 37 home runs, 167 RBIs, and a .256 batting average. One of the best examples of his ability to dominate the game was a week in August 1943. “Butch Nieman may never be known as one of the major leagues’ outstanding performers but right now he is providing the finest clutch hitting in baseball,” wrote Judson Bailey of the Associated Press. “In the last week he personally has decided four important games for the Braves. On Friday he hit a two-run homer in the tenth inning to beat the Cubs 5-4. Last Saturday Nieman hit his second home run of the season in the ninth inning to beat Brooklyn and on Sunday he smashed a ninth-inning double to down the Dodgers a second time. In the same week he also hit a triple in the 12th inning whipping the Cubs.”1

Elmer Leroy Nieman was born on February 8, 1918, one of two sons of Werner and Katherine Nieman. The family was among several that had migrated from their native Germany to Herkimer, Kansas, where they eked out a living as farmers and filling in with odd jobs. Elmer was called Butch as a youngster and the nickname remained with him. At Marysville High School he grew into a formidable 6-foot-2, 195-pound athlete who excelled in football, basketball, and track.2 The school did not have a baseball team but that did not stop him from listing in his high-school yearbook under senior ambitions, “Wants to be second to none to Babe Ruth.”3

Butch played on a town team that toured the state. Lee Dodson, a fellow Kansan and minor-league pitcher for the Topeka Owls, recalled the prodigious power Nieman displayed in the mid-1930s when the Marysville American Legion team visited Topeka. “I remember going to the game on my bicycle and boy did (Nieman) ever reward us. He hit three home runs. They were majestic shots, and I thought, God can this guy hit.” Johnny Bulkley, another Topeka Owls player, also recalled seeing Nieman during his high-school years: “[When it comes to hitting,] Butch was in a league by himself.”4 In 1947, after his major-league days were done, Nieman joined Dodson and Bulkley on the Owls and led the Western Association with 138 runs, 114 RBIs, and 29 home runs.

Nieman received a football scholarship to Kansas State University, where he played two-way football as a halfback and defensive back and majored in business administration and physical education.5 His son, Kurt, said, “My grandparents were from very humble backgrounds and did not understand him wanting to go to college. They wanted Butch to work and earn money.”6 Nieman enrolled in college in 1937 towards the end of the Depression and struggled financially to stay in the program. His daughter Holle, the oldest of four offspring, remembered being told that he attended classes without money to buy the textbooks, instead relying on classmates and the school library.7 Playing baseball was mainly a summer activity as Butch said in an interview with the Christian Science Monitor’s Ed Rumill: “During the summer while I was in college I played in the Ban Johnson League. … It was for kids who wanted to play summer ball but did not want to hurt their amateur standings. You got your room and board and some kind of job around town. We played three nights a week and on Sundays —about 70 or 80 games a season.”8

In his junior year A Kansas State football program said of Nieman, “Elmer Butch Nieman, southpaw halfback, specializes in skirting the end and harassing his opponents with left-handed bullet passes. He is swift enough to outdistance most opponents and has the nickname the Herkimer Hurricane.” It was during this period that Butch met his future wife, Mary, at a dance. After a whirlwind courtship, they married and Nieman looked to secure his future. While a career in professional football was a possibility, he finished his third year at Kansas State and signed with the Boston Red Sox. “Billy Evans signed me, he was the minor-league boss of the Red Sox organization. Nobody scouted me but a hometown fan recommended me to someone connected with the Little Rock club, and Evans came with a contract. So in 1940 I reported for spring training at Little Rock.”9

Thus began a 13-year baseball odyssey that would see the family live in seven minor-league cities as well as Boston. Nieman had a brief stay in Little Rock and was sent to the Canton Terriers of the Class C Middle Atlantic League. As an outfielder he batted a very respectable .306 in 121 games, drove in 85 runs, and led the team with 21 home runs. He was named to the league all-star team.

Nieman started 1941 with the Class A Scranton Red Sox, but after 16 games was sent to Greensboro of the Class B Piedmont League. A short time later the Red Sox sent him back to Canton, where he found his batting eye, playing in 90 games and ending the season with a .321 batting average and 10 home runs. The following season was another year of bouncing around. As Nieman recalled, “In 1942 I was with Scranton again, but during the season they traded me to the Elmira club, out of the Red Sox organization. I thought that I was hitting the ball pretty good but Scranton seemed to need infielders more than outfielders. They traded me for an infielder.”10

The Elmira Pioneers were a Detroit Tigers affiliate in the Class A Eastern League. Elmira struggled that year with a 62-77 record and soon became a part of the Philadelphia Athletics organization. Nieman provided the only power on the team hitting nine home runs, but he batted a mere .206.11 Still, it was in Elmira that Nieman first displayed his ability to produce the big hit. “Butch Nieman’s home run with the bases loaded gave the Pioneers an even break with the Springfield Rifles in a doubleheader recorded a sportswriter. “He is the only player in the league to hit a ball over the Dunn Field fence this year.”12

Soon after, the Braves acquired Butch from the Athletics, signed him to a minor-league contract with the Hartford Bees of the Eastern League, and told him to report to the Braves’ wartime 1943 spring-training camp in Wallingford, Connecticut. The contract was for $275 per month.13

The Braves recalled Nieman on May 2, 1943. That season he played in 101 games for manager Casey Stengel. This was not Nieman’s first appearance on a Boston baseball field. In 1939 his Kansas State football team had lost to Boston College, 38-7, at Fenway Park. In one of Nieman’s first appearances as a pinch-hitter, the Boston Globe’s Roger Birtwell reported, “He gave the ball a terrific ride to deep right field, and although it was only an out, it enabled (Connie) Ryan to race down to third after the catch.14

In that story Birtwell referred to Nieman as “part-Indian.” This was one of several times that reporters referred to Butch as a Native American. His son Kurt explained that his father had a dark complexion and daughter Holle said Butch went along with the Native American references as he would “do just about anything to help the team sell tickets.” Kurt said his grandparents spoke German; even his birth certificate was written in German.15

Nieman patrolled the outfield with Tommy Holmes and Chuck Workman, primarily playing left field. As a batter, curveballs gave him trouble, but he had his moments.16

On June 15 against the Phillies, Nieman almost hit for the cycle, with a single, double, and triple in four at-bats. It was a good effort in a losing cause as the Braves went down to a 6-4 defeat. On July 22 he combined power and speed when he hit a 390-foot line drive to center field, easily landed on third, and then scored the game-winning run when the Cubs’ Lennie Merullo threw the ball over the catcher’s head. On July 30 Nieman figured in all three runs as Boston defeated Cincinnati 3-0. In the first inning he hit a home run with a man aboard, and in his next plate appearance he walked, stole second, and scored on a double by catcher Phil Masi.

The following week Nieman launched a streak of game-winning hits. The Wisconsin State Journal recapped the streak: “On August seventh his home run in the ninth defeated the Dodgers, 7-4. The next day he doubled in the ninth inning to score Tommy Holmes in a 5-4 victory Six days later he launched a triple in the twelfth to beat the Cubs, and then on September 19th his fourteenth-inning homer edged the Phillies.”17 The Sporting News also took notice of Butch’s emergence: “The way Nieman has been going Casey Stengel is patting himself on the back for deciding on Elmer as a regular. For the boy has come through like a champion recently, and put some smiles into a situation which needed brightening.”18

Nieman’s bat remained hot during August. On the 19th he hit his fifth home run on a drive that landed halfway up the right-field bleachers in a 7-5 losing effort against the Reds. Four days later, Butch led the Braves offense with three hits (including a pair of doubles) in a 14-5 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals. On August 31 Nieman faced the Giants’ premier pitcher, Van Mungo, and took the game in hand, scoring three runs and hitting a three-run homer for a 6-0 drubbing of New York. Two days later he hit a game-winning triple in the 10th inning against the Phillies. Casey Stengel remarked, “That lad Nieman certainly has helped us. Why, in less than four weeks he has won seven games in the late innings with extra-base hits.19

On September 6 Nieman broke a finger on his throwing hand during a pregame fielding drill which was expected to place him on the sidelines for three weeks. Wearing a splint on his little finger, he said, “Let me play and see how it goes.”20 On the 11th he entered a game against the Giants as a pinch-runner, scored a run and then stayed in the game and hit a single in the 13th inning of a losing effort. On the 19th he led the Braves to a doubleheader sweep of the Phillies with a two-out, two-run homer in the 14th inning of the second game

The Braves finished in sixth place in 1943. Nieman played in 101 games with a .251 batting average, 15 doubles, 8 triples, 7 home runs, and 46 RBIs. He had seven three-hit games, walked 39 times and struck out the same amount.

Nieman’s efforts during the year did not go without notice, as he was named to the 1943 Major League All-Star freshman team. Before returning home he toured with a group of major leaguers led by St. Louis Browns executive Charles DeWitt, playing in cities from Erie, Pennsylvania, to Pendleton, Oregon. Fellow Braves Tommy Holmes and Phil Masi were among his teammates.

Having earned little money during his college and minor-league days, Nieman was hoping to parlay his successful ’43 season o into a sizable pay increase to help support his family of four. He was also concerned that induction into the military would create a further hardship for Mary and his two daughters. In that spirit he returned the Braves initial contract unsigned and asked for more money.

Braves president Bob Quinn responded by telling Nieman, “With conditions as they are today and with the decent treatment you had here last season, I cannot understand you.” He ended the letter by saying, “It seems that I am all wrong with the present day ball players.”21 Before spring training Nieman wrote to Quinn advising him that he might be called for induction before the season started and asked his advice on whether he should remain at home or report to the Braves. “If I wait in Kansas to find out my status spring training will practically be over before I get there. Financially I can’t afford to lose the month without pay and then be inducted before the season opens. There will be too long a period before my family or I receive anything from the government. Please advise me your personal views on the subject.”22 Quinn responded, “My opinion is that you should report to our training camp and request your [draft] Board permit you to take your physical in Boston. … This is War and our club has tried to do everything they could in such an emergency, so do not worry about what it would cost us. We will pay your transportation back to Kansas if you are inducted.”23

Nieman passed his physical in Boston and was classified 1A. He and another Braves player, Connie Ryan, were told to await a call from the Navy. The order to report for induction was not sent until the following year, and was dated August 6, 1945, with a report date of August 17.24 August 6 was the day the United States dropped an first atomic bomb on Hiroshima and nine days later Japan surrendered. The Sporting News reported, “Outfielder Butch Nieman of the Braves missed his draft call by a whisker. He was to have been inducted August 17 but was excused because he was 27 years old, the [new] age limit set a few days earlier.”25

Bob Coleman succeeded Casey Stengel as the Braves’ manager in 1944. One of Coleman’s first projects was to help Nieman become a more consistent hitter. “I noticed that he hit most of his balls to right-center field. In most parks that is the deepest spot. A lot of his long balls were being caught,” Coleman observed. “The answer was to get him turned around a little more towards right field as he stood in the batter’s box.”26

Butch responded with his best season in the major leagues —a batting average of .265 in 468 at-bats, 16 doubles, 6 triples, and 16 home runs. As in the previous year, he matched his walks and strikeouts with 47 each. He had 11 three-hit games and homered twice in a game four times.

Nieman went on a tear from late May through the end of June in 1944. On May 24 he hit a home run off Pittsburgh’s Rip Sewell for the Braves’ only run in an 8-1 defeat. The next day Nieman’s single drove in Connie Ryan with the only score of the game in a 1-0 victory over the Pirates. On May 28 he blasted two home runs in a 7-3 win over the Cubs. Two more home runs followed on June 3 as the team squeezed out a 5-4 win against Bucky Walters and the Reds. Four days later Nieman delivered another home run, his seventh of the season, in a 6-2 loss to the Giants. He and Tommy Holmes homered on June 22, providing a cushion for Jim Tobin’s five-inning 7-0 no-hitter against Philadelphia.

Nieman smacked home runs 11 and 12 on August 1 game against the Pirates. On August 6 some inept running led to an odd triple play by the Dodgers. According to The Sporting News, “A delayed triple play was made by the Dodgers against the Braves with Max Macon, Tommy Holmes and Chuck Workman filling the bases. Butch Nieman hit to Ed Stanky at second. His throw to the plate retired Macon and Mickey Owen’s toss to first nipped the batter. Workman, thinking there were three outs, was standing ten feet from first base and tagged out by shortstop Bobby Bragan in a rundown.27

Nieman started September as he did August, homering twice in a 13-inning 2-1 win on the 2nd against the Phillies. The Boston Globe’s Dan Kane wrote, “They said Butch Nieman could not hit. When he was a Red Sox farm hand in Scranton two years ago he had a minor eye affliction. So the Red Sox decided he would never become a big league hitter and they let him go. But anyone who thinks Butch can’t belt them should ask [Philadelphia pitcher] Bill Lee.”28 Another Globe sportswriter, Clif Keane, wrote of Nieman’s game-winning hit against the Dodgers on September 18, “Southpaw pitches that have looked like split peas to ‘Butch’ Nieman in the past loomed like a medicine ball to the big Braves outfielder yesterday. Butch unloaded on a Tom Sunkel pitch in the 10th inning scoring Phil Masi and giving the Tribe a 6-5 victory.”29 Wrapping up the season, Charles Billington wrote, “Boston home run production rose from 39 to 79 (thanks in part to Butch Nieman’s team-leading 16). The Braves still had the worst team batting average and attendance dropped to 208,000, their lowest since 1924.”30 They went 65-89, finishing in sixth place for the second consecutive year.

Although Nieman played appeared in only 97 games in 1945 and batted just .247, he hung up some impressive numbers. He hit 14 home runs, five as a pinch-hitter, the most for any Boston-Milwaukee-Atlanta pinch-hitter in a season. He drove in 56 runs and stole 11 bases.

An appendix operation after the 1944 season left Nieman at a disadvantage when he reported to spring training on March 31. In addition to veterans Tommy Holmes and Chuck Workman, two rookie outfielders, Carden Gillenwater and Bill Ramsey, had shown promise. By the end of camp, Nieman was named to the starting outfield. However, with five outfielders on the roster, he was shuffled in and out of the lineup depending on the pitching matchup and which player had the hot bat at the moment. On April 20 his first home run of the season was a three-run ninth-inning smash that gave the Braves a 6-5 victory over the Phillies in Philadelphia. Two days later Nieman made another bid for a game-winner against the Phillies with a ninth-inning tie-breaking home run, but Philadelphia came back in the bottom of the inning to win the game 7-6. On the 24th his three-run walkoff homer defeated the Dodgers, 8-6. The victory placed the Braves in the first division, ahead of the Dodgers. Three days later Nieman hit his fourth home run in his last five games in an 8-7 win against the Phillies. He was named The Sporting News Player of the Week. During June Nieman was platooned, although he was always in the lineup against the Phillies, a team he seemed to own as a hitter. After a 0-for-20 hitless streak, manager Coleman put him in the lineup against Philadelphia and he responded with a base hit. On June 20 he hit a home run and was part of a 16-hit attack with the Tribe besting the Giants at the Polo Grounds, 15-10.

The Braves swept a doubleheader on July 1 against the St. Louis Cardinals. In the first game, Nieman pinch-hit and smacked a three-run walkoff homer in the 10th inning of a 6-3 win. On the 6th he hit a pinch-hit grand slam in a 13-5 victory over the Pirates.

In the second game of a twin bill on July 19, Nieman continued his home-run hitting with a three-run drive that tied the score against the Reds. He later scored the winning run in the 10th inning, when Carden Gillenwater drove him home from second base. As The Sporting News reported, “With Red Sox boss Joe Cronin out of the picture, Butch Nieman of the Braves looks like the premier pinch-hitter of 1945.”

Manager Bob Coleman resigned on July 30 after a nine-game losing streak and was replaced by Del Bissonette, a coach on Coleman’s staff. On August 3 Nieman’s bat came alive in the second game of a doubleheader with Brooklyn, when he delivered a two-run home run in a 5-3 win. Nieman hit his 13th homer on August 9 as the Tribe beat the Cubs, 7-3. More than 13,000 fans showed up on September 2 for a Tommy Holmes doubleheader “Day.” Between the games, Holmes, who led the league in batting that season, was given a Packard car. Butch helped celebrate with another pinch-hit home run, this time in the ninth inning of the second game against the Phillies, but the Braves lost the game, 5-4. The remainder of the month was a quiet one for the Kansan, who was plagued with the flu in the last week of September. He played his final major-league game on September 30, the last day of the season, pinch-hitting without success. The Braves ended the season in sixth place for the third consecutive year with a record of 67-85.

In 1946 there was a new manager, Billy Southworth. The Braves had not produced a winning record since 1938 and the owners were determined to turn the ship around. Southworth had managed the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and two World Series victories during the war years and the Braves outbid the Redbirds for his services.31 Southworth also brought with him several Cardinals players including outfielders Danny Litwhiler and Johnny Hopp.

For the second time in three years, Nieman was a holdout and reported late to camp, which could not have endeared him to the new manager. In addition to the former Cardinal outfielders, Bama Rowell had returned from the service and Tommy Holmes, Chuck Workman, and Carden Gillenwater remained from the previous year. Despite his power and timely hitting, Butch had become a part-time player in 1945 and with a crowded roster he and several other Braves were shipped to Indianapolis in the American Association. Nieman did not fare well in Indianapolis, and after appearing in 25 games and hitting an anemic .163, he was sent to the Chicago White Sox’ Double-A team in Little Rock. Butch had come full circle, after starting his career with Little Rock in 1940. He hit nine home runs in 110 games for Little Rock, but his batting average at season’s end was .227, and the following year he landed with the Topeka Owls, an independent Class C team. Nieman was back home in his native Kansas and for the next five years as a player and eventually player-manager he thrived in the Western Association. In 1947 he was the league MVP with a batting average of .311, 29 home runs, and 114 RBIs.

In midseason of 1948 Nieman became Topeka’s player-manager and continued his torrid pace with a .326 batting average, 34 home runs, and 33 doubles. The Sporting News reported, “Butch Nieman of the Western Association club does a little bit of everything. He plays first base and the outfield and in the second game of a doubleheader with Salina on May 9 he proved he could pitch. He left his first base post in the seventh inning to stop Salina with the bases loaded and after his mates made eight runs in the ninth Butch struck out the side to get credit for the win.”32 Later in the month he hit for the cycle and drove in five runs.33

In a game at Muskogee, Nieman hit a tremendous shot that “went out of the park, across the street and through a window, later measured by his teammate Lee Dodson at 510 feet.”34 In a pregame ceremony that evening Nieman received “among other gifts, $101.28 collected from the crowd, a billfold, a ham and a cigarette case and lighter.”35 Daughter Christine recalled that there was a Hormel Ham sign in the outfield, and players hitting over the sign received a ham. “We had a lot of hams around the house,” she added.36 The next season, 1949, was Nieman’s best; he batted.329 with 26 home runs and 29 doubles.

In 1950 Nieman shared most of the hitting honors with an 18-year-old player for Joplin named Mickey Mantle. Mantle led the league in hits and had a .383 batting average. The 32-year-old Nieman batted .314, out-homered Mantle, 28 to 26, and drove in 149 runs to Mantle’s 136 RBIs.

The year also marked the addition of a third daughter, Jan, to the Nieman family.

Butch Nieman’s final year in professional baseball —and perhaps his best —was 1951. While his batting average dipped to .268, he continued his home-run pace with 28 four-baggers and managed to improve the Owls from a 58-81 record the previous year to a league-leading 74-44 record to capture the Western Association title. The year was also the first when Topeka had an integrated team with African Americans Solly Drake and Milton Bohannion. Drake later made the majors with the Cubs, Dodgers, and Phillies. Butch’s son, Kurt (who was born in 1951), recalled how his father told him that during trips to Western Association cities like Muskogee and Joplin, Nieman would have to make accommodations for Drake and Bohannion’s housing and transportation.37

Although it was a good year for the Owls, the Midwest was hard hit with flooding and the team claimed the title after the playoffs were canceled. Topeka was ahead of Joplin by a half-game and thus took home the pennant. After the season Nieman retired from professional baseball at the age of 33 and started a career working in a supervisory capacity for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, a job that lasted 30 years. At Topeka he had led the league four consecutive seasons in RBIs, five in home runs, and four in walks. He was named to the Western Association’s all-star team four times.

Although it was a good year for the Owls, the Midwest was hard hit with flooding and the team claimed the title after the playoffs were cancelled. Topeka was ahead of Joplin by a half-game and thus took home the pennant. At the end of the season, fans and local merchants presented the player-manager with a Ford automobile. This was his first new car and a welcome addition to the family which had grown with two new children in the past two years. Nieman retired from professional baseball at the age of 33 and started a career working in a supervisory capacity for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, a job that lasted 30 years. At Topeka he led the league four consecutive seasons in RBIs, five in home runs, and four in walks. He was named to the Western Association’s all-star team four times.38

The Owls further honored Nieman by bringing him back on Opening Day in 1952 to raise the 1951 pennant. He commented to a sportswriter, “I will remember baseball long after baseball will remember me.”39

While his playing days were over, Nieman’s love of the game was not. He co-founded the Babe Ruth League in Topeka for boys 13-15 and later for older age groups. His son Kurt recalled, “He did not like Little League, especially the pitching, where there was no limit to the number of throws. He never encouraged pitchers to overthrow or throw curveballs until the age of 17. He preached mixing speeds and had a stringent rule that a player could only throw seven innings per week. He always dressed in a full uniform for a game and stressed the fundamentals. He wanted his players to always think ahead, run in and out of the dugout, and always maintain a defensive position in the field. After batting practice my dad would step to the plate and could still hit the ball 350 feet well into his 40s.”

Kurt Nieman was athletic and made the all-conference team in baseball and football during high school. When he asked his father whether he should pursue a baseball career, Butch (reminded of his own shortcomings) told him, “Son, you can’t hit a curveball.”40 As a quarterback at Fort Scott Community College, Kurt was number four in the nation in passing yards and led the team to the national junior college championship. He then enrolled at the University of Kansas, where he was converted to a running back. Daughter Christine remembered that in the Babe Ruth League, “He had his players call him Mr. Nieman and he was tough on them. He doubted they would make the major leagues but he wanted them to look good on the field. When he died, many came to the funeral and said ‘I played baseball for your dad and he made a big difference in my life.’“41

All of Nieman’s children recalled him as a soft-spoken, reserved man who spoke little of his big-league experience. He was particularly proud that although he never earned his college degree, all four of his children were college graduates.

Mary Jeannette Smith Nieman died April 1, 1991; she was 70. Two years later, on November 2, 1993, Elmer Leroy “Butch” Nieman died while in a nursing home in Topeka. While he did not think that baseball would remember him, his Kansas community did. In 2005 he was honored by his hometown College Hill Neighborhood Association with a spot on its Wall of Fame. (In the same year, Kurt was inducted into the Fort Scott Community College Athletic Hall of Fame.) In July 2014 Nieman was inducted into the Shawnee County Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Judson Bailey (Associated Press), Eugene (Oregon) Register, August 13, 1943. The three games referenced were on August 7, 8, and 12, 1943.

2 Ed Rumill, Baseball Magazine, July 1945.

3 Holle Nieman Baskett, interview by Sidney Davis, May 13, 2014. (Hereafter Holle Nieman interview).

4 Topeka Capital Journal, undated clipping from 1952.

5 Rumill.

6 Kurt Nieman interview by Sidney Davis, April 2, 2014. (Hereafter Kurt Nieman interview).

7 Holle Nieman interview.

8 Rumill.

9 Rumill.

10 Rumill.

11 digitalballparks.com/Eastern/Elmira4.html, accessed May 17, 2014.

12 Corning (New York) Evening Leader, August 5, 1942.

13 Hartford Bees Contract, February 27, 1943. A copy of the contract was sent to the author by Holle Nieman Baskett.

14 Roger Birtwell, Boston Daily Globe, April 21, 1945.

15 Kurt Nieman interview.

16 Rumill.

17 Rumill.

18 Jack Malaney, The Sporting News, August 19, 1943.

19 Jerry Nason, Boston Daily Globe, September 4, 1943.

20 Melville Webb, Boston Daily Globe, September 8, 1943.

21 Bob Quinn letter to Nieman, January 24, 1944. Copies of correspondence between Quinn and Nieman were provided to the author by Holle Nieman Baskett.

22 Butch Nieman letter to Bob Quinn, March 1, 1944.

23 Bob Quinn letter to Nieman, March 6, 1944.

24 Selective Service, Order to Report for Induction, August 6, 1945.

25 The Sporting News, August 23, 1945.

26 Rumill.

27 The Sporting News, August 17, 1944.

28 Dan Kane, Boston Sunday Globe, September 3, 1944.

29 Clif Keane, Boston Daily Globe, September 19, 1944.

30 Charles N. Billington, Wrigley Field’s Last World Series: The Wartime Chicago Cubs and the Pennant of 1945 (Chicago: Lake Claremont Press, 2005).

31 John C. Skipper, Billy Southworth, A Biography of the Hall Of Fame Manager and Player ((Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013).

32 The Sporting News, May 26, 1948.

33 The Sporting News, June 9, 1948.

34 Kurt Nieman interview.

35 Kurt Caywood, Topeka Capital-Journal, June 14, 1995.

36 Christine Nieman Gettig, interview by Sidney Davis, May 19, 2014 (hereafter Christine Nieman interview).

37 Kurt Nieman interview.

38 E-mails from Kurt Nieman and Holle Nieman Baskett, July 16, 2014.

39 Topeka Capital-Journal, August 16, 2004.

40 Kurt Nieman interview.

41 Christine Nieman interview.

Full Name

Elmer Leroy Nieman

Born

February 8, 1918 at Herkimer, KS (USA)

Died

November 2, 1993 at Topeka, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.