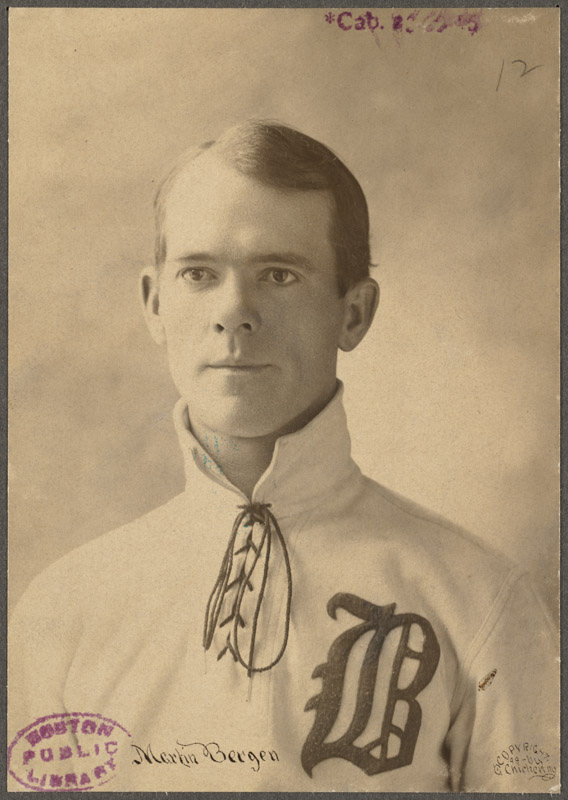

Marty Bergen

Marty Bergen was one of the finest catchers in the National League during his brief stint. His defense was admired throughout the league. As one sportswriter noted in 1898, “Martin Bergen is a kingpin of catchers, and without him the Bostons would be probably in second place or even lower down the ladder.” Although he was nothing special in the batter’s box, the 5-foot-10, 170 pound Bergen had an extremely strong and accurate arm. He finished his career with a .265 batting average, 44 doubles, 15 triples, and 10 home runs in 344 games. Giants owner Andrew Freedman, for one, coveted his fine play and more than once approached Boston about trading the player.

Marty Bergen was one of the finest catchers in the National League during his brief stint. His defense was admired throughout the league. As one sportswriter noted in 1898, “Martin Bergen is a kingpin of catchers, and without him the Bostons would be probably in second place or even lower down the ladder.” Although he was nothing special in the batter’s box, the 5-foot-10, 170 pound Bergen had an extremely strong and accurate arm. He finished his career with a .265 batting average, 44 doubles, 15 triples, and 10 home runs in 344 games. Giants owner Andrew Freedman, for one, coveted his fine play and more than once approached Boston about trading the player.

Over the course of his short baseball career, Bergen became increasingly despondent and irrational, continually accusing his teammates of plotting against him and of doing things to harm him. There were numerous verbal altercations and even some physical ones between the catcher and the rest of the team. At times he jumped his club and returned home to the comfort of his family. Naturally, this didn’t sit well with management and his teammates. He exasperated more than one manager. In April 1899, after Bergen’s oldest son died, the ballplayer’s mind started to stray from reality. By the end of the season, he was accusing his teammates of using his son’s death against him. Bergen more than once threatened his teammates’ lives and they were at their wits’ ends in dealing with their unstable catcher. The players feared for their safety and hoped that he wouldn’t return the following spring. As it turned out, they were right to be concerned. Bergen slaughtered his entire family that January and then killed himself.

Martin Bergen was born on October 25, 1871, in North Brookfield, Massachusetts, to Michael and Ann, nee Delaney, Bergen. Michael and Ann were both born in Ireland, immigrating to the United States in 1865 at the end of the Civil War. Michael supported his wife and six children working in a shoe factory. The Bergens’ third child, Martin was the first son. His brother William (Bill) was the sixth child and only other boy. Like Marty, who was seven years older, Bill was a catcher, learning the trade from his elder brother. Although he was one of the poorest hitters in major league history, Bill caught for Cincinnati and Brooklyn from 1901 to 1911, and both Bergen brothers were regarded as among the finest catchers of their time.

Marty grew up in North Brookfield, a small town in Worcester County about 75 miles from Boston. He played on his local independent club, known as the Brookfields. One of his teammates was Connie Mack, also a North Brookfield resident. In 1892 the twenty-year-old Bergen joined Salem in the New England League, his first professional club. In 59 games at catcher he batted .247. After the regular season for several years to come, Bergen rejoined the Brookfields during the late fall. In 1893 he joined Northampton, Massachusetts, an independent club, and played three games for Wilkes-Barre in the Eastern League. At the end of that season, he was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates, managed by his neighbor Mack.

In 1892 Harriet (Hattie) Gaines moved to North Brookfield from New York State after securing a position at a local mill. She soon met Bergen, and they were married on July 11, 1893. A few years later they purchased a small farm, called Snowball Farm, on Boynton Street. The couple had three children: Martin, born circa 1894; Florence born a year later; and Joseph a year or two after his sister.

In 1894 the Pirates assigned Bergen to Lewiston in the New England League for seasoning. The practice of farming wasn’t legal at that time in baseball history, thus the transfer became an issue and Bergen’s contract with Pittsburgh was voided. He hit .321 in 97 games for Lewiston. At the end of the year he was drafted by both the National League’s Washington Senators and the Western League’s Kansas City Cowboys. Baseball officials assigned Bergen to Kansas City. However, club president and field manager Jimmy Manning soon became exasperated with his new catcher. Bergen was a moody sort who constantly expressed his displeasure. At one point in mid-season, Bergen walked away from the club for a week over some supposed slight while the team was in Minneapolis. In 113 games he batted a strong .372 with 188 hits and 118 runs scored. At the end of the year Marty was drafted by the Boston Beaneaters of the National League. He had been recommended to manager Frank Selee by pitcher Kid Nichols, a Kansas City native. Nichols had seen the catcher in a game during the 1895 season when he stopped at home during a western trip.

Before Bergen would join Boston, team owner Arthur Soden had to make a trip to North Brookfield to convince the sensitive player that he was valued and would be treated well by his new club. He played for Boston from 1896-99, catching 63, 85, 117 and 72 games during those four years. He gained a reputation as one of the finest catchers in the league. One Sporting News article described him as “the greatest throwing catcher that the game ever produced.” Connie Mack, a catcher himself, stated that Bergen was the only catcher he’d seen gun down a base stealer at second from his knees. From the get-go though, Bergen had trouble with his teammates. As one reporter explained in May 1896, “Martin Bergen, the young backstop…is unpopular with his fellow players on the Boston team. Bergen is a sullen, sarcastic chap, never associates with the players, and always nurses a fancied grievance. His disposition handicaps his playing talents.”

Boston was one of the top teams in the league during Bergen’s stint behind the plate. They finished fourth in his rookie season. The next two years they copped the pennant, before finishing second by eight games in 1899. Kid Nichols, Boston’s ace, explained how important the catcher was to the team, “Baltimore beat us the next three years, after we lost (catcher Charlie) Bennett. Then we got Marty Bergen from Kansas City and won the pennants again in 1897 and 1898.” Despite his catching abilities and the team’s success, Bergen was often the topic of trade rumors because of his moodiness, melancholy, inability to mesh with teammates, and penchant for sulking and leaving the club. However, not all the trade rumors originated that way. New York Giants owner Andrew Freedman tried to work a trade for the catcher on more than a few occasions. At the time of Bergen’s death, most within the game assumed that he would be playing for the Giants in 1900.

Even as a teenager, Bergen had showed signs of anxiety and stress. He would become moody, pout, and storm off if he felt that he wasn’t getting his fair share of applause. In 1891, his first professional season, he engaged in a brutal fistfight with one of his teammates. During his time in Boston, Bergen had several run-ins with teammates and opponents. Newspapers commonly referred to his erratic behavior, describing him as “sullen and silent” and highlighting his moodiness, aloofness, and inaccessibility.

Near the end of the 1898 season, Bergen threatened his teammates after an altercation on the bench. He declared that he would “club them to death” at the end of the season. He slapped teammate Vic Willis in a St. Louis hotel dining room. As the Nebraska State Journal noted via wire reports, “Martin Bergen, the eccentric catcher of the Boston team, is in trouble again…Bergen, always surly, often lets his temper get away from him, and makes breaks from which there is no provocation. He hit pitcher Willis in the face because he sat down at the same table in the dining room. The incident was hushed up at the time, but it is likely that Bergen will be traded before the opening of next season, as Selee says he has stood Bergen’s crankiness as long as he can.” On July 20, 1899, the Boston team was traveling by train to Cincinnati. The men were having a good time playing cards, but Bergen sat withdrawn from his teammates. When the train stopped in Washington, D.C., Bergen hopped off, jumping the club and returning home to North Brookfield. Another wire article described Bergen as, “the hardest man in the National League to manage.” The writer described Bergen as “the erratic catcher of the Boston club, who has deserted the club annually since his connection with it and always at a time when his services were most needed. His grievances are fanciful. Of a moody disposition he imagines that his fellow players are leagued against him and are intent on bringing about his downfall. The contrary is the case. Manager Selee and his players have treated the great backstop with unusual consideration.”

Boston Globe reporter Tim Murnane rode out to the Bergen farm to assess the problem and to coax the moody catcher into rejoining the Beaneaters. Bergen lamented that his teammates were hounding him and that at least four of them shouted, “Strike him out!” when he was at bat. He claimed his teammates and team owner Soden were avoiding him, and he was upset because manager Frank Selee wouldn’t give him a day off to visit his family. He was also dismayed by the $300 fine he received for jumping the club. Furthermore, he didn’t like the tone of a telegram he had received from Soden during his absence. Bergen then claimed he was injured and had to return home because only his lifelong friend and hometown physician, Dr. Louis Dionne, could care for him. He finally rejoined the club a week and a half later.

Bergen registered numerous complaints about his teammates throughout the years. From the other perspective, Bergen’s bizarre actions took a toll on his teammates. According to The Boston Braves: 1871-1953, by the end of 1899 some did not want him to return to the club, plus several were seriously concerned about their safety around the disgruntled player. As the Sandusky Star noted, “It is now conceded that the Boston nine dropped out as a champion factor largely because of the trouble between the players and Martin Bergen, the catcher. Ever since Bergen’s first desertion of the nine there has been a feeling of bitterness, intensified by the cordial reception that Bergen received when he returned to the team. The public did not understand the facts as well as the players, and the players felt aggravated that the misunderstanding had arisen.” As the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier put it, “Marty Bergen is accused of creating dissention in the Boston team, which is the cause of the champions’ recent defeats.”

When the team was at home in Boston, Bergen always spent the night at his farm. Neighbors said he would play with his children all day, rarely associating with others. Throughout the 1899 season Bergen pestered Selee for time off to return to his family. He would play a few games and then ask to go home. On April 24, 1899, Bergen’s son Martin, 5, passed away from diphtheria while his father was out of town. After two weeks at home with his family, he rejoined the club, but he quickly descended into a downward spiral. Toward the end of the season he was estranged from his teammates. He claimed that they continuously and maliciously reminded him of his son, causing him a great deal of stress. Unhappy, Bergen jumped the club yet again at the end of September without a word and went home for a few days complaining of a sore hand.

Several sources report that Bergen suffered a broken hip at the end of the 1899 season. The story goes that this injury threatened his career and sent him into a depression, which spiraled into the tragedy of January 1900. However, this doesn’t match the evidence. Bergen was bothered by hip problems throughout his career and he had an operation for an abscess on his right hip on January 28, 1899, the result of sliding into home near the end of the 1898 season, but that didn’t stop him from playing the entire year. Nor were there stories about any excessive lingering effects during the 1899 season. Furthermore, he played the entire game on October 13, the next-to-last day of the season, and he was not injured and didn’t play in the season finale. Bergen visited his doctor after the season ended without mentioning any significant hip troubles. The catcher was the subject of numerous trade rumors and that winter even hosted a sportswriter or two at his house. An injury was never mentioned by any of those parties. Surely an injured hip would have been at the center of any trade article about a catcher.

The hip surgery in January 1899 required him to be under anesthesia for four hours. His doctor and family noted that he never seemed to recover mentally from the operation. Most important to Bergen’s frail state was the death of his five-year-old son. This was compounded by guilt over the fact that he was away from home at the time, on the road with the ball club.

Immediately after the 1899 season, Bergen talked with his physician and confidant, Dr. Dionne, who later told reporters that all seemed fine, but the doctor soon heard from family, friends, and neighbors that Bergen was acting “wild.” When the doctor visited, he found Bergen pacing in front of his house. It didn’t take much prodding for the ballplayer to “open his heart” in a tearful rant. He confessed to Dionne that he had “strange ideas” and said he was afraid that he was “not right in the head.” Bergen admitted that he couldn’t remember much about the past baseball season. All he remembered was that a man came up to him after his last game and congratulated him on a fine performance and gave him a cigar. Bergen was afraid to smoke the cigar because he believed it was poisoned. He was also concerned that Dionne and his wife were trying to poison him. He refused to take any medicine they gave him if he didn’t first mix it himself.

Bergen believed the National League had found out that Dionne was his doctor and had paid Dionne to kill him. He described being frightened of his teammates, feeling that they were out to kill him. Bergen said he always sat sideways on the bench, in the clubhouse, and on trains in case his teammates decided to attack. He wished he had quit baseball so he could find some peace. He also believed that people in general, including the Boston team and other National League players, were plotting against him.

The doctor gave Bergen a bromide and told him to repeat the dosage in three hours. However, the doctor did give him some advice that seemed to work. Bergen chewed and sucked on tobacco constantly. The doctor suggested that he quit the habit as it was contributing to his nervousness and anxiety. Bergen did so and felt better for a time. Later Dionne had what he described as a nice, pleasant conversation with Bergen, who got up to leave the office and said, “This has been a pleasant talk, and it is strange how it has rattled me.” Bergen also confided in his pastor that he believed himself to be insane and feared his own actions. He asked for help, but none was forthcoming from his doctor, priest, family, or community.

On the night of January 18, 1900, a Thursday, the Bergen family ate a hearty meal and turned in. When Bergen’s father found the bodies the following morning, the beds had been slept in. Some time in the early morning, Bergen arose and started preparing for the day. He removed the ashes from the stove, the home’s primary heat source, indicating that the stove had cooled overnight. Bergen then placed paper in the stove for lighting though he hadn’t yet retrieved wood from outside, as the inside pile was depleted.

Then, for some unknown reason, he snapped. Stressed and delusional, Bergen slaughtered his family. First he attacked his wife in the bedroom, hitting her multiple times in the head with the blunt side of an axe. She fell, dying on one of the beds. Bergen then whacked his son once with the sharp side of the axe. The boy died in the other bed. In the kitchen Bergen killed his daughter, smashing her multiple times in the head with the blunt end of the axe. Bergen then retrieved a razor and stood in front of a mirror in the kitchen. He sliced his own throat, nearly severing his head, and fell beside his daughter.

On January 20 the entire family was laid out in the Bergen home for family and friends to view. They were transported to St. Joseph’s Church for the funeral ceremonies and interred North Brookfield’s St. Joseph’s cemetery.

After Bergen’s deeds on January 19, 1900, Dr. Dionne repeatedly made comments that Bergen was “insane” and a “maniac.” The doctor believed that the situation was out of his control and out of his purview. Finally acknowledging Bergen’s mental illness, the Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane wrote that Bergen “was entitled to the undivided sympathy of the baseball public, as well as players and directors.” In the wake of the tragedy, North Brookfield made efforts to better educate professionals and the community about mental health issues.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin

Sources

Minor league statistics provided by Ray Nemec

Ancestry.com

Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Maine

Boston Daily Advertiser

Boston Globe

Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette

Chicago Tribune

Daily Iowa State Press, Iowa City

Daily Review, Decatur, Illinois

Fort Wayne News

Fort Wayne Sentinel

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves: 1871-1953. University Press of New England, 2004.

Nack, William, “Collision at Home,” Sports Illustrated, June 4, 2001, p. 74

Nebraska State Journal

New York Times

Smith, Sam, “Nichols: “We Stayed in and Pitched,” Baseball Digest, June 1951, p. 75

Sporting Life

Sporting News

Washington Post

Full Name

Martin Bergen

Born

October 25, 1871 at North Brookfield, MA (USA)

Died

January 19, 1900 at North Brookfield, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.