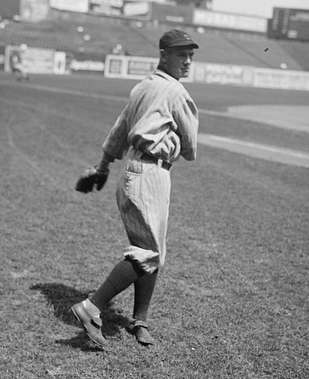

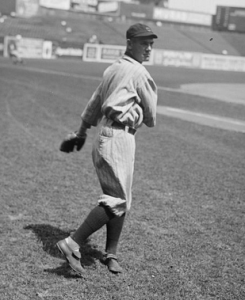

Ray Chapman

Ray Chapman, star shortstop for nine seasons with the Cleveland Indians, might have ended up in the Hall of Fame had he not been fatally injured by a Carl Mays fastball on August 16, 1920, at the Polo Grounds. An ideal number two hitter who crowded the plate, the 5-foot-10, 170-pound Chapman led the league in sacrifice hits three times. His total of 67 sacrifices in 1917 is a major league record, and he stands in sixth place on the all-time career list with 334. Chapman was also a legitimate offensive force in his own right: the right-handed batter led Cleveland in runs scored three times during his career, and paced the entire American League in runs and walks in 1918, with 84 of each. He also led the Indians in stolen bases five times, and his 52 thefts in 1917 remained the franchise record until 1980. In addition to his offensive skills, Chapman was also an excellent fielder who led the American League in putouts three times and assists once. Put it all together, and Chapman was, in the view of the Cleveland News, the “greatest shortstop, that is, considering all-around ability, batting, throwing, base-running, bunting, fielding and ground covering ability, to mention nothing of his fight, spirit and conscientiousness, ever to wear a Cleveland uniform.”

Ray Chapman, star shortstop for nine seasons with the Cleveland Indians, might have ended up in the Hall of Fame had he not been fatally injured by a Carl Mays fastball on August 16, 1920, at the Polo Grounds. An ideal number two hitter who crowded the plate, the 5-foot-10, 170-pound Chapman led the league in sacrifice hits three times. His total of 67 sacrifices in 1917 is a major league record, and he stands in sixth place on the all-time career list with 334. Chapman was also a legitimate offensive force in his own right: the right-handed batter led Cleveland in runs scored three times during his career, and paced the entire American League in runs and walks in 1918, with 84 of each. He also led the Indians in stolen bases five times, and his 52 thefts in 1917 remained the franchise record until 1980. In addition to his offensive skills, Chapman was also an excellent fielder who led the American League in putouts three times and assists once. Put it all together, and Chapman was, in the view of the Cleveland News, the “greatest shortstop, that is, considering all-around ability, batting, throwing, base-running, bunting, fielding and ground covering ability, to mention nothing of his fight, spirit and conscientiousness, ever to wear a Cleveland uniform.”

As good as Chapman was on the field, he was even more beloved for his infectious cheerfulness and enthusiasm off it. One of the most popular players in Cleveland Indians history, Chapman was a gifted storyteller who played the piano and once won an amateur singing contest. The good-humored shortstop also had a wide circle of admirers outside the game — his show business friends included Al Jolson, William S. Hart and Will Rogers. One newspaper described Chapman as a man who “was as much at home in the ballroom as on the ball diamond.” His tragic death in 1920 sparked one of the largest spontaneous outpourings of grief in Cleveland history.

Raymond Johnson Chapman was born to Everette and Barbara Chapman on January 15, 1891 on a farm near Beaver Dam, Kentucky, about 80 miles southwest of Louisville. The family settled in Herrin, a town in southern Illinois in 1905. Ray, the middle of three surviving children, did odd jobs as a boy and sometimes worked in the mines. Young Chapman played his first organized ball in 1909 for the semipro club in Mount Vernon. In 1910 he went to Springfield, Illinois, where he played every position except pitcher and catcher. “He was a very flashy player,” recalled a Springfield teammate. “And he could run. He was a beautiful runner, the way he could pick up his knees. He was very fast, had a good arm, and was a good fielder, although at times a little erratic. And he was very jolly, a jolly guy. Always laughing, talking, singing.” From Mount Vernon, Chapman went on to Davenport of the Three-I League, where he hit .293 with 75 runs scored and 50 stolen bases in 1911. Cleveland purchased Chapman’s contract toward the end of the season and assigned him to Toledo of the American Association.

Chapman faced a traffic jam at shortstop when Cleveland brought him up to the big club in August 1912. He had batted .310 for the Mud Hens in 140 games, with 49 steals and 101 runs scored, but the Naps had two other promising shortstops. One rival, Roger Peckinpaugh, had played 15 games for Cleveland in 1910 but spent 1911 in the minors. The second, Ivy Olson was the team’s regular shortstop the previous year (third baseman Terry Turner had played shortstop for the team from 1904 to 1910). Cleveland began the 1912 season with Olson at shortstop and Peckinpaugh, a favorite of manager Harry Davis, in reserve. Just two days after Chapman’s arrival, however, Davis was replaced as manager by centerfielder Joe Birmingham, who doubted Peckinpaugh’s ability to hit big league pitching. Birmingham also benched Olson, who had 27 errors at shortstop in 56 games and was nagged by minor injuries. Birmingham then turned to Chapman, who, though shaky in the field, took advantage of his opportunity by hitting .312, as Cleveland won 22 of the 31 contests he appeared in.

Chapman hit .258 in 1913, his first full season with Cleveland, and led the American League with 45 sacrifice hits, to form a strong middle infield with the Naps’ legendary 38-year-old second baseman, Napoleon Lajoie. In 1914 Chapman broke his leg in the spring and only played in 106 games. With Lajoie no longer on the club, the team collapsed. Chapman bounced back the next season to hit .270, and his 101 runs scored were 59 more than anyone else on the team. He was again plagued by leg ailments in 1916, when he hit only .231 in 109 games. Despite his physical problems, Chapman’s prowess was widely recognized. In 1915 the Chicago White Sox tried to obtain him from Cleveland, but, after being rebuffed, had to settle for acquiring outfielder Shoeless Joe Jackson instead.

In 1917 Cleveland finished well back of Chicago in the standings, but Chapman blossomed. Sparked by his all-round play, the Indians won 32 of their last 47 games to finish 88 — 66, in third place. From August 31 to September 24 they won 17 of 20 games, including a 10-game winning streak in which Chapman hit .517 with four steals of home. In an exhibition game against the Braves in Boston on September 27, Tim Murnane Day, Chapman won a loving cup for the fastest time circling the bases, 14 seconds. Chapman finished the year with a .302 batting average and 98 runs scored to go along with his club-record 52 stolen bases.

Chapman’s production declined in 1918, as he finished the year with just a .267 average and 28 extra-base hits. Despite those numbers, Chapman led the American League in runs scored with 84, thanks in large part to his league-leading 84 walks, which helped him post a career-high .390 on-base percentage. After the season ended in September, Chapman complied with the War Department’s work-or-fight order and enrolled in the Naval Auxiliary Reserve as a second-class seaman. He spent three months as a deckhand on the steamer H.H.Rogers, which sailed on the Great Lakes, and was captain of the Naval Reserve baseball and football teams. Chapman was also a sprinter on the track squad, where he specialized in the 20- and 100-yard dash. His best time in the latter event was 10.0 seconds. His service ended with the armistice in November 1918. The following year, Chapman rebounded to hit .300 in 115 games for the Indians, who finished in second place with an 84 — 55 record, their best showing in franchise history.

After the season Chapman married Kathleen Daly, daughter of the millionaire president of the East Ohio Gas Company. Tris Speaker, Ray’s closest friend on the Indians, was the best man. Before the 1920 season began, Chapman gave some thought to retirement from baseball — he was already secretary — treasurer at the firm Pioneer Alloys. Speaker was the new Indian manager, however, so Chapman decided to play at least one more year to help his pal and owner James Dunn win the team’s first pennant.

During the thrilling 1920 season the scrappy White Sox were again contenders for the AL pennant, though they would soon be gutted for having thrown the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. The surging New York Yankees, who like the Indians had never won a pennant, were led by Babe Ruth‘s unprecedented slugging. In mid-August, however, Speaker’s club clung to slim leads over both teams and Ray Chapman was having one of the best seasons of his career. On the morning of August 16 he had a batting average of .304, with 97 runs scored, 52 walks, 27 doubles and 49 RBI.

That afternoon — rainy and dark — the Indians were in New York for a game against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds. The Yankees’ starting pitcher, right-hander Carl Mays, was a surly man unpopular with both his teammates and other players. One of the few hurlers who threw underhand, Mays had a reputation as someone who liked to pitch batters tight. “Carl slings the pill from his toes,” wrote Baseball Magazine in 1918, “has a weird looking wind-up and in action looks like a cross between an octopus and a bowler. He shoots the ball in at the batter at such unexpected angles that his delivery is hard to find, generally, until along about 5 o’clock, when the hitters get accustomed to it — and when the game is about over.”

Chapman was 0 for 1 when he led off the fifth inning with Cleveland ahead 3-0. With a count of one ball and one strike, Chapman, who batted and threw right-handed, hunched, as usual, over the plate, waiting for the next pitch. He always popped back when the ball was thrown. Mays looked in and, detecting that Chapman was slightly shifting his back foot — probably to push the ball down the first base line — released a fastball, high and targeting the inside corner. The gray blur sliced through the heavy, humid air, possibly a strike. Chapman did not move.

Many of the players and 20,000 fans heard an “explosive sound” — Babe Ruth said it was audible where he stood far out in right field. Sportswriter Fred Lieb, sitting in the downstairs press box about fifty feet behind the umpire, heard a “sickening thud.” The ball dribbled out toward the pitcher’s mound on the first base side. Mays fielded it and threw it to first baseman Wally Pipp for the out, apparently thinking the ball had struck the bat. Pipp turned to throw the ball around the infield, but froze when he glanced home. Chapman had sunk to his knees, his face contorted, blood streaming from his left ear. Yankee catcher Muddy Ruel tried to catch Chapman as his knees buckled. Umpire Tommy Connolly ran toward the grandstand yelling for a doctor. Speaker rushed over from the on-deck circle to tend to his stricken friend, who was trying to sit. Speaker thought Chapman wanted to get up and rush Mays. Finally, two doctors (one of them a Yankee team physician) arrived, applied ice and revived Chapman. He walked under his own power across the infield toward the clubhouse in center field, but his knees gave way again near second base. Two teammates grabbed the shortstop, put his arms around their shoulders, and carried him the rest of the way.

Mays remained near the mound, showed the ball to umpire Connolly, and told him that the fateful pitch had been a “sailer”; a rough spot on its surface had caused it to move further inside than he expected. (That summer AL owners had complained to League President Ban Johnson that umpires were running up expenses by throwing out too many balls unnecessarily, so Johnson issued a notice ordering umpires to “keep the balls in the games as much as possible, except those which were dangerous.” Thus, teams often played with balls that were scuffed and browned by dirt and tobacco juice.) The game continued, eventually a 4 — 3 Indian victory.

After the game New York manager Miller Huggins, a lawyer, took Mays to the police station nearest the Polo Grounds to file a report on the incident. Mays was later cleared of all wrongdoing in the incident. The stricken Chapman, meanwhile, was at St Lawrence Hospital nearby on 163rd Street, where doctors — operating on Speaker’s authority — made a three-inch incision in the base of Chapman’s skull, finding a ruptured lateral sinus and plenty of clotted blood. They removed a small piece of his fractured skull. Kathleen Day Chapman, pregnant with the couple’s first child, was immediately summoned to New York. Chapman rallied briefly, but he died early the next morning before his wife’s arrival.

Kathleen, Speaker, and Joe Wood accompanied the body back to Cleveland; Chapman was seen off on his final journey by a large crowd of mourners at Grand Central Station. As word of Chapman’s death spread around the League, players on the Boston, Washington, St. Louis, and Detroit rosters — with Ty Cobb among the loudest — demanded that Carl Mays be banned from baseball. A few Indians players warned Mays that he should not show his face in Cleveland again. Many newspaper editorials railed against the bean ball and the New York Times called for batting helmets to be required. The league soon took steps to keep cleaner balls in play.

Chapman’s funeral at St. John’s Cathedral on August 20, Cleveland’s largest in years, was attended by many baseball dignitaries and thousands of Indians fans. Thirty-four priests participated in the service. A blanket made of more than 20,000 blossoms purchased by mourning fans was placed on his grave. Flags in the city were flown at half-staff. Tris Speaker and Jack Graney were so overwhelmed by grief that they did not attend.

The Cleveland — New York game of August 17 was canceled because of Chapman’s death. (Cleveland’s victory in the tragic game had kept the Indians in first place.) The demoralized Indians lost to the Yankees 4 — 3 when play resumed on August 18 and dropped seven of nine games after the incident. Graney said, “We feel as if we did not care if we ever played baseball again. We cannot imagine playing without Chappie.” It “looks now very much like the White Sox will win out,” noted The Sporting News. But Speaker, almost too weak to hold a bat, rallied the club when he returned on August 22. With the addition of pitcher Walter (Duster) Mails, and future Hall of Famer Joe Sewell, who took Chapman’s place at shortstop, the Indians won 24 of their final 32 games and defeated Brooklyn in the World Series. The team awarded Mrs. Chapman a full World Series share.

Speaker never blamed Mays for Chapman’s death, but many others, including Graney, held him responsible. Miller Huggins left Carl Mays at home during the Yankees’ September road trip to Cleveland. “It is an episode which I shall always regret more than anything that has ever happened to me,” Mays said, “and yet I can look into my own conscience and feel absolved of all personal guilt. I have long ceased to care what most people think about me. I have a few good friends I can depend on and that is all I need and all I want. In the meantime I have a wife and a family to support.”

Kathleen Daly Chapman, once a baseball fan, never attended another game. On February 27, 1921 she gave birth to a daughter, Rae-Marie. She married a cousin two years later. The former Mrs. Chapman died in Los Angeles on April 21, 1928 after swallowing a poisonous fluid. She was accompanied at the time by her mother, who said her daughter had been recovering from a nervous breakdown. The Daly family insisted that Kathleen had taken the poison accidentally. The Chapmans’ daughter went to live with her grandmother, but died a year later during a measles epidemic.

Ray Chapman is buried in Section 42, Lot 16 of Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland. Chapman’s younger sister Margaret Joy visited the site for many decades afterward to pay her respects. “Ray is there all by himself,” she told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1995. “Ray loved Cleveland. He thought it was such a wonderful place. So did I. I still look in the papers to see how the Indians are doing.”

Sources

Newspapers

Cleveland News

Cleveland Plain Dealer

The Sporting News

Books

William Curran. Big Sticks. William Morrow and Company, 1990.

Harry Grayson. They Played the Game. A.S. Barnes and Co., 1945.

Bill James. The Bill James Historical Abstract. Villard Books, 1988.

Bill James. The new Bill James Historical Abstract. The Free Press, 2001.

Bill James and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. Simon and Schuster, 2004.

Fred Lieb. Baseball as I Have Known It. University of Nebraska Press, 1977.

Lawrence S. Ritter. The Glory of Their Times. Vintage Books, 1985.

Mike Sowell. The Pitch That Killed. Collier Books, 1989.

Articles

Richard Derby. “In Memorium (sic): Mays’ Beaning of Chapman Recounted.” Baseball Research Journal. SABR, 1984.

Carl Mays. “My Attitude Toward the Unfortunate Chapman Affair.” Baseball Magazine, November 1920.

“Who’s Who on the Diamond.” Baseball Magazine, June 1918.

Internet

www.baseball-almanac.com

www.thebaseballpage.com

www.baseballlibrary.com

Pamphlets

Corinne Taylor Gregory, “Once There Was a Dam: Stories and Recipes,” 1982.

Full Name

Raymond Johnson Chapman

Born

January 15, 1891 at Beaver Dam, KY (USA)

Died

August 17, 1920 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.