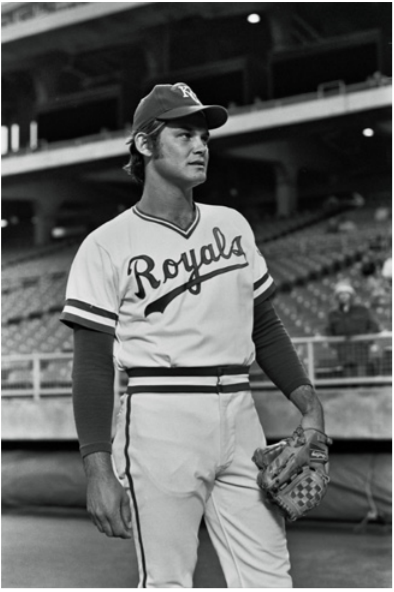

Steve Busby

On June 18, 1974, Paul Splittorff threw a two-hit shutout against the Brewers in Milwaukee. After the game Splittorff and his roommate, Steve Busby, were talking about no-hitters. Splittorff did not consider himself to be a no-hit-type pitcher. But he had a list of pitchers who he considered could throw a no-hitter every time out — which included Nolan Ryan and Busby. Busby, who had pitched a no-hitter the previous season, said, “I got all over him for saying this because I really don’t consider myself to be a no-hit pitcher. I think I’ve been more fortunate than a lot of other pitchers because obviously it takes a lot of luck to pitch one.”1 The next day Busby threw his second no-hitter. Busby would be forever associated with the no-hitter and rotator cuff surgery, but there is much more to his story.

On June 18, 1974, Paul Splittorff threw a two-hit shutout against the Brewers in Milwaukee. After the game Splittorff and his roommate, Steve Busby, were talking about no-hitters. Splittorff did not consider himself to be a no-hit-type pitcher. But he had a list of pitchers who he considered could throw a no-hitter every time out — which included Nolan Ryan and Busby. Busby, who had pitched a no-hitter the previous season, said, “I got all over him for saying this because I really don’t consider myself to be a no-hit pitcher. I think I’ve been more fortunate than a lot of other pitchers because obviously it takes a lot of luck to pitch one.”1 The next day Busby threw his second no-hitter. Busby would be forever associated with the no-hitter and rotator cuff surgery, but there is much more to his story.

Steven Lee “Buzz” Busby was born on September 29, 1949, in Burbank, California, to Marvin and Betty Busby, who were of English and German descent. Marvin played football at USC and professionally for the Los Angeles Dons of the All-American Football Conference.2 This had an influence on his son, Steve, who grew up preferring football to baseball. When Marvin’s football days were over, he worked as a petroleum and chemical engineer. Betty taught American history at the University of California at Berkeley before leaving to raise their children. Busby said he was raised to believe that the team was more important than the individual and that individual accomplishments didn’t mean much if they didn’t contribute toward the team winning.3

Busby grew up in Fullerton, California, and was a three-sport star at Union High, excelling in basketball, baseball, and football. (Hall of Famers Arky Vaughan and Walter Johnson also attended the school.) While in high school, Busby threw two no-hitters. He cited his baseball coach there as one of his early influences. “Jim Bass is the best teacher of fundamentals … catching, throwing, pitching mechanics,” Busby said. “I learned pitching mechanics from him, learning to win from him.”4

Playing football during his senior year, Busby suffered a knee injury that required an operation. In 1967 the San Francisco Giants selected Busby in the fourth round of the June draft. When Busby’s knee gave out during a workout, the Giants discovered that there were still lingering effects from the injury and cut their bonus offer in half. Busby decided to accept a scholarship to the University of Southern California and to play for the legendary coach Rod Dedeaux.

In 1968 Busby went 8-3 and batted .422 and was named the team’s most valuable player for the USC freshman team.5 In 1969, his sophomore year, Busby required surgery to relocate the ulnar nerve in his right arm. His arm strength was gone and he realized that he had to start developing other pitches. Before the surgery he threw 80 percent fastballs; after, he developed a slider and made the transition from thrower to pitcher. Busby’s arm strength eventually returned and he became a more complete pitcher.

In 1971 Busby compiled an 11-2 record for the Trojans with a 1.92 ERA in 21 games and made the All-American team. Busby was the team’s leading pitcher, and though he lost an early-round game to Southern Illinois University in the College World Series, he redeemed himself in the deciding game. Busby struck out Southern Illinois’ Bob Blakely with the bases loaded to seal the 7-2 victory for the Trojans.

Busby’s major at USC was business administration He also studied computer technology because he enjoyed the mathematical analysis. While at USC, Busby took a creative writing class taught by the creator of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling,6 and was inspired to write science-fiction novels. Busby thrived on challenges, and he wanted to see if he could “make all the pieces fit together.”7 His novels were described as not the “stars and galaxy kind, but the Rod Serling type … the psychological experience … and some occult.”8

Busby was selected by the Kansas City Royals in the second round of the secondary phase (June) of the amateur draft in 1971. Despite being one semester short of graduating and having a year of college eligibility left, Busby signed with the Royals for a $37,500 bonus. He was described in The Sporting News as “not merely being early maturity, rather a happy blend of intelligence, perspective and competitive intensity, tempered with self control. He seemed already to know how to pitch. If he didn’t pitch well, he knew why not and he knew how to accept victory or defeat.”9 Busby credited Dedeaux, saying, “I attribute a lot of my attitude to Coach Dedeaux. He always emphasized that you should do the best you can and not blame anyone else for failure. Don’t downgrade anyone else.”10 He added, “I didn’t appreciate the things Rod Dedeaux taught us until I got into pro ball. He taught me how to win including the psychological part of the game, how to recognize the small things: whether the outfielder was left-handed or right-handed, watching people in the infield, and looking at every possible way to beat you, whether it was good fielding, a good pickoff move, by intimidation or being lucky.”11

Pitching for the Royals’ San Jose farm team (California League), Busby compiled a 4-1 record with an 0.68 ERA, giving up only three earned runs in 40 innings and striking out 50. In the Florida Instructional League he continued to impress, with a 5-2 record, 1.50 ERA, and a league-leading 67 strikeouts in 60 innings.

It was felt that Busby had a shot to make the major-league roster out of spring training in 1972; he was the talk of the newcomers and had the poise of a veteran. He started the season at Triple-A Omaha. On May 4 Busby struck out eight consecutive Tulsa batters and broke up the opposing pitcher’s no-hitter in the fifth inning en route to a 7-1 victory. In another game against Tulsa he struck out 16 in a pitching duel he won over Jim Bibby. Busby twice came close to pitching no-hitters during the season. The first time his bid was broken up with one out in the ninth, the second in the seventh. His manager, Jack McKeon prophetically counseled Busby “not to worry, that I’d pitch a couple of no-hitters and it’ll be in the big leagues.”12 Busby led the league in strikeouts (221), innings pitched (217), and complete games with 17. He compiled a 12-14 record with a 3.19 ERA, for a team that the Royals felt victimized its pitchers with its poor defense. Busby said he benefited from McKeon’s counsel, particularly on pitch selection.13

Busby got a surprise call-up after Omaha’s season after Dick Drago’s jaw was broken by a line drive on September 1. He made his major-league debut on September 8, 1972, started against the Minnesota Twins at Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium. Cesar Tovar and Rod Carew greeted Busby with singles and the Twins took an early 1-0 lead. Busby settled down and pitched a complete-game 3-2 victory, striking out seven and allowing only five hits.

In Busby’s third start, against the California Angels in Anaheim, just a 15-minute drive from his childhood home in Fullerton (and the first time his parents saw him pitch in the majors), he lost a grand slam after smacking pitcher Lloyd Allen’s offering over the left-field fence. First-base umpire John Rice had called time before the pitch to eject Jerry May for suggesting that Rice speak to his tailor about “adding an extra panel in his suit.” Royals manager Bob Lemon and Dick Drago also were ejected. When play resumed, Busby singled to center for his first major-league hit and collected two RBIs. Busby got two other hits, and the three were his only major-league base hits, because the American League adopted the designated hitter the next season. (A good all-around athlete, Busby was against the DH.) Busby started five games for the Royals in ’72 and was 3-1 with a 1.58 ERA.

In 1976 Busby found out what happened on that night when he was convalescing in the hospital. Busby’s roommate and best friend on the team, Paul Splittorff, came to see him. Busby recalls years later with a chuckle, “My arm is strapped to my chest and I’m still kind of woozy from all the medication they were giving me… He said hey I got to fess up to you and he told me the story about what he had said and he hid behind somebody as he was yelling it. He was the one who suggested to Rice about the tailor. He said you know I feel terrible about it. I was completely out of it. ‘I said yah, whatever.’ It was a month later, I finally came to and realized what he had told me. I had to corner him about it. He said, ‘I figured you’re not going to come back and pitch anymore anyways so I might as well get it out of the way and I’m not going to have to worry about rooming together.’ That was kind of my impetus to get back to pitch the major league level and room with him again so I can give him a hard time.”14

At the start of the 1973 season expectations were high for Busby. He was slated to be in the starting rotation and there was speculation from McKeon, the Royals new manager, that Busby had the makeup to win 20 games. “There isn’t a hitter that can intimidate Busby,” McKeon said.15 Busby and Doug Bird combined to no-hit the Detroit Tigers in an exhibition game, Busby pitching the first six innings. He followed with seven hitless innings against the Cardinals. Busby was the Opening Day starter, but struggled, losing to California. In his first four starts he was 1-2 with an 8.04 ERA. He lasted only one inning and gave up five runs in a 16-2 defeat by the Chicago White Sox. Busby had some stiffness in his shoulder and was held back a few days before his next start. He recalled McKeon telling him that if he didn’t show improvement in his next start, he would be sent down to work it out in Omaha.16

Did he ever show improvement! On April 27, a cold evening that Busby described as perfect for pitching, he threw the Royals’ first no-hitter, beating the Detroit Tigers, 3-0. Busby became the 14th rookie to throw a no-hitter. He was wild, walking six. He had trouble locating his breaking pitches and threw mostly fastballs. At the time Busby downplayed the individual achievement, noting that first baseman John Mayberry bailed him out with a line-drive double play in the ninth. “It was blind luck. It had nothing to do with skill,” Busby said of his feat.17 More recently he said, “It was less than 40 degrees, I was wilder than a Marsh hare, the Tigers were a veteran ballclub that didn’t feel like swinging the bats.” 18 (The umpire whose time-out call cost Busby his grand slam, John Rice, was the home-plate umpire for the no-hitter.)

Busby pitched well in his next game but then slumped and his record was 4-9 on July 2. But from then until the end of the season he was 12-6, helping the Royals to finish in second place in the American League West. Against Milwaukee on July 10 Busby struck out 13, tying the Royals team record at the time. He finished the season with a 16-15 record and a 4.23 ERA. It was the most wins by an American League rookie since 1968 and Busby was named The Sporting News American League Rookie Pitcher of the Year.

Despite high expectations for 1974, the Royals struggled early in the season and were two games under .500 and 4½ games behind Oakland on June 11. Owner Ewing Kaufman fired general manager Cedric Tallis, whose trades were credited with making the Royals the most successful expansion team in baseball history at the time. The timing was disruptive and the team was also grumbling about manager Jack McKeon and his handling of the pitching staff.

Busby got off to a better start in 1974, 8-6 with a 3.66 ERA going into his June 19 start in Milwaukee. Busby threw a gem. He walked only George Scott to lead off the second inning and retired the final 24 batters to record his second no-hitter, defeating the Brewers 2-0. Busby became the first and as of 2016 the only pitcher to throw no-hitters in his first two major-league seasons. Modestly, he said, “There were some outstanding plays behind me. I had good stuff but it could have been a four- or five-hitter.”19 Busby recalled that both no-hitters were low-scoring games and he had to focus on keeping the opposition off the boards rather than thinking about the no-hitter.20

Busby started his next game by retiring the first nine batters he faced. He broke the American League record by retiring 33 consecutive batters. (The record was tied in 1977 and broken in 1998.21) In both of Busby’s starts after his no-hitters he pitched 5⅓ no-hit innings.

Busby started the season 13-9 with a 3.31 ERA to earn his first All-Star Game selection, but did not pitch. The Royals were a streaky team and won 16 of 22 games in late August to pull to within four games of the division-leading A’s. But on a long homestand they lost 10 of their next 11 games to fall out of contention.

On September 17, Busby became the Royals second 20-game winner, but it was bittersweet as he hadn’t won a game in three weeks as the Royals slid from contention. “It has no value because we didn’t accomplish what I consider valuable, a championship,” he said.22

Controversy struck the club again when McKeon fired hitting coach Charlie Lau before the last home game of the season. The move was sharply criticized by the players. Busby, the team’s player representative, was very critical of the move. “We’ll never win a pennant with this type of thinking,” he said. “… If this organization is not interested in winning, then I don’t want to be part of it. … You can’t win a championship without horses … and they have taken away one of the very best horses they’ve had available.”23 It was rumored that McKeon was jealous of Lau and that the players went to Lau for help rather than McKeon.

Busby finished the season at 22-14 with a 3.39 ERA and a club record 292⅓ innings pitched. Busby was in the top 10 in almost every pitching category including WAR (seventh) and strikeouts per nine innings (fourth). The innings pitched may seem high by today’s standards but Busby was only ninth in the league in innings pitched.

Controversy followed the Royals into the 1975 campaign. Busby resigned as player representative in May. Rumors were swirling that he threatened to leave the team in New York on May 18, because he had been at odds with McKeon and he wanted Buck Martinez and not Fran Healy, who caught both his no-hitters, to catch him. Busby dispelled any rumors of quitting after his meeting with McKeon and general manager Joe Burke.24

Busby was having his best season and started out 10-5 with a 2.57 ERA. He began to experience pain in the front of his shoulder, tendinitis, but a new pain in the rear of his shoulder began to appear. He compensated by altering his pitching motion, a step that caused mechanical issues. In a Sports Illustrated article in August 1978, Busby detailed what happened next: “On the 25th of June I threw 12 innings in Anaheim and won 6-2, but I struggled for the last seven. It was really a chore to throw. The next time I pitched was July 1 against Texas. Normally I recuperate fast between starts, but this day I just couldn’t throw well. I was having strength problems: I couldn’t grip the ball well and I had a lessened ability to snap my wrist. I couldn’t even make a tight fist. … I pitched on through the middle of September with very little success.”25

Busby was named to his second All-Star Game and pitched two innings in relief. After two months of speculation, Jack McKeon was fired as manager of the Royals on July 24 and was replaced by Whitey Herzog. GM Burke cited McKeon’s poor relationship with his players and the media as the main reason. The club was a disappointing 50-46, 11 games behind the A’s. Herzog brought back hitting coach Charlie Lau.

The Royals finished seven games behind Oakland. Busby was held out the last week of the season because of shoulder soreness. He recalled, “By that time, I had no sensation of strength when I threw the ball.”26 He finished with an 18-12 record and a 3.08 ERA 260⅓ innings.

After the season Busby saw Dr. Frank Jobe, who prescribed different therapies. Busby thought his problems had been caused by bad mechanics and began an offseason training program. Busby was counted on to be a key contributor to the Royals’ hopes to win the American League West crown in 1976. Dr. Jobe recommended that Busby pitch until he could no longer be effective. He started the season on the disabled list, joined the team in early April and pitched his first game on April 18. The Royals lost, 6-0; Busby gave up two runs in six innings but walked seven. After the game he was optimistic: “There is no doubt in my mind I’m healthy. My arm is fine.”27 Herzog added, “Busby threw freely and had no pain. He threw better than he did all last September.”28 Busby pitched an impressive game against the Yankees on May 1 and “removed any doubts about the condition of his arm.”29 But the relief over Busby’s arm was short-lived. He left his May 12 start in the fifth inning as a precaution. At the time the seriousness of his arm condition was not known. Busby said, “It’s not really serious. It’s a muscle problem, an injury most pitchers suffer during spring training.”30 At the time it was reported that Busby was recovering from an elbow problem that he suffered late in the 1974 season.

Busby was held out of his next start and then was put on a pitch count. He pitched 15 innings in his next three starts restricted to 100 pitches and gave up only one run. (Though Busby has been said to be the first pitcher held to a pitch count, this was common practice at the time for a pitcher recovering from an injury.) Through June 2 Busby pitched in only seven games, but the Royals were off to a great start and were leading the American League West.

By June 15 Busby’s season was described “an on again off again comeback” in The Sporting News.31 Herzog summed up the situation: “We can’t go on like this not knowing what his status is. If he needs complete rest, than let’s go that route.”32 On June 22 Busby gave up nine runs to the White Sox; he said, “The arm feels good, but the results aren’t.”33 On July 6 Busby gave up four runs in seven innings to the Yankees. One of the Yankees said, “He had nothing, no fastball, no curveball.”34 Both Busby and Herzog knew this, too, and decided to find out what was wrong.

Busby recalled, “[Dr. Robert] Kerlan [Dr. Jobe’s partner] ordered me to have a shoulder arthrogram. Dye is injected into the joint, and if it leaks out into the surrounding tissue, there is a problem — and it showed that I had a tear in the rotator cuff. Rest wouldn’t help an injury that serious. If I were to pitch again, I would have to have surgery.”35 Busby was done for the season; he finished with only 13 starts, a 3-3 record with a 4.40 ERA in 71⅔ innings. The tear in his rotator cuff was caused by the upper bone in the arm rubbing up against the top bone in the shoulder. Surgery lasting 3½ hours was required to cut the shoulder open, sew up the hole, cut three-quarters of an inch off the shoulder bone and shave off the back of the upper arm bone to reduce the friction.36 This was the first time this procedure was performed on an active pitcher. Dr. Jobe performed the groundbreaking surgery on July 19, 1976. Jobe had previously done the surgery on tennis players and it was expected that Busby would regain full use of his arm, but his future effectiveness as a pitcher was unknown. A torn rotator cuff had ended many pitchers’ careers including that of Don Drysdale. Dr. Jobe recommended that Busby seek other employment, but Busby wasn’t ready to give up.

Meanwhile, the Royals went on to win their first American League West Division title and Busby found solace in the team’s accomplishment. Busby said, “It was such a great feeling.”37 The Royals lost the ALCS to the Yankees on Chris Chambliss’s walk-off home run. Busby worked on a rehab program overseen by Dr. Jobe. Given the nature and severity of the injury the Royals were not counting on him. They took a gamble and left Busby exposed to the 1977 expansion draft. Busby was not selected at least for two rounds (24 players selected) by the Toronto Blue Jays and Seattle Mariners.

There was no timetable for Busby’s return; there was no one to whom one could compare his situation. He was confident he would return and could be effective with reduced velocity if he could control his breaking pitches. Busby appeared in one minor-league game and fared poorly. He reinjured his left knee while altering his pitching delivery and strengthening his shoulder. Dr. Jobe operated on the knee.

Baseball had taken a toll on Busby’s personal life. He had placed baseball as his first priority, which led to a separation from his wife. During the summer of 1977 he got back together with his wife and two daughters and placed family as his first priority.

Although the Royals were not counting on Busby for the 1978 season, he showed up in camp after more rehabilitation to his arm and knee and made the staff out of spring training. He started out well with a shutout, then was hit hard in his next three starts and was sent to the minors. Busby was called up in September and appeared in three games.

During spring training 1979 the 29-year-old Busby was competing for the fifth starter/long reliever role for Kansas City. He made the squad and posted a 6-6 record and 3.63 ERA, appearing in 22 games and starting 12.

During the offseason, Busby had arthroscopic surgery on his oft-injured right knee. In 1980 he competed again for the fifth starter/long reliever role. He made the staff and appeared in relief until he was sent to the minors in April. While in the minors, Busby was impressive with Omaha, posting a 2.48 ERA and throwing a one-hitter. He was recalled by the Royals and started six games. Busby posted a 1-3 record with a 6.17 ERA. The Royals wanted to use left-handed reliever Ken Brett in the playoffs and released the 30-year-old Busby on August 29, just two days before he would have been playoff eligible. Busby expressed his frustration. “It was disappointing watching the playoffs, not being able to pitch every year through 1980. I wanted to pitch so bad, I could taste it.”38 It is one of the great what-ifs: If Busby had been healthy from 1976 to 1980, would the fortunes of the Royals had been different? They lost the ALCS to the Yankees three times and lost the 1980 World Series to the Phillies.

In 1981 Busby was reviewing his business options, including broadcasting, a car dealership, and a beverage distributorship, when Herzog invited him to spring training with the St. Louis Cardinals as a nonroster player. Busby did not make the team and he retired. In 1984, at age 34, Busby was considering a comeback. “It’s been nagging at me for three years,” he said.39 But he decided against pitching winter ball and his pitching days were over. In 1986 Busby and Amos Otis were inducted as the inaugural members of the Royals Hall of Fame.

While Busby was rehabilitating, former Royals play-by-play announcer Buddy Blattner recommended that he get into broadcasting. In 1981 Busby worked as a weekend sports anchor with the local Kansas City NBC affiliate. In 1982 he had two job offers, from the Boston Red Sox and Texas Rangers. He chose the Rangers because they were closer to home, and in Boston he would be filling the big shoes of the legendary Ken “Hawk” Harrelson.40 Busby became one of the rare ex-athletes to become a play-by-play announcer. He described how this came to be: “When I first started out, I was very fortunate to have one of the all-time greats in broadcasting, Merle Harmon, that I was paired with down here in Texas, and Merle made it a point to get me to learn how to do play-by-play and help him out during ballgames. He didn’t have to do it for nine innings of play-by-play. So the first spring training that we worked together, he and I went out to games that we weren’t broadcasting and took a tape recorder and Merle made me do five, six, seven innings of play-by-play. Then we would go back to the hotel after the game and listen to it. He would critique me and give me pointers and really got me going. If it hadn’t been for someone like that taking the time and making the effort to help me get settled in to being a broadcaster, I never would have done it. Merle was one of the nicest people in the world. You don’t find many people in this business or for that matter in most competitive businesses who are willing to take the time to train somebody else and help them advance themselves.”41

In 1996 Busby worked as the play-by-play announcer for the Royals alongside his close friend, Paul Splittorff. Busby struggled with his retirement from baseball for many years even though he had made a career as a broadcaster. “I always said that it doesn’t bother me and that it was part of the game, and that was a bunch of garbage,” he said. “It bothered me. It hurt. That injury and the subsequent injuries stripped me of my identity.”42 Busby had what he would describe as a “rebirth” in late 1997. “I finally got OK with me being me. Just saying, ‘OK this is who you are, this where you are, and what do we do from here on out?’’’43 Busby spent more time with his children. He took a year off from broadcasting and began working with high-school pitchers, teaching them the finer points of pitching.

As of 2016, Busby was the play-by-play announcer for the Rangers. He said being a former player gave him the advantage of having a very comfortable conversation with his partner, Tom Grieve.44 Their broadcasts have been described as “watching baseball, telling stories, eating cookies and pastries, and most of all, having fun.”45

Last revised: February 2, 2017

Notes

1 Gib Twyman, “No-Hit Hurler? ‘Not Me! Says Busby,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1974: 13.

2 Wil A. Linkugel and Edward J. Pappas, They Tasted Glory: Among the Missing at the Baseball Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998), 128.

3 Author’s interview with Steve Busby on April 20, 2016 (hereafter Busby interview).

4 Randy Covitz, “Busby’s heart lasted longer than his arm,” Kansas City Star June 5, 1986: 3B.

5 Busby player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

6 Busby interview.

7 Rosemarie Ross, “Busby: Can He Win 20 in His First Full Season?” The Sporting News, April 21, 1973: 20.

8 William Barry Furlong, “0-Hit Kid Steve No Stereotype,” unidentified newspaper clipping from Busby player file.

9 Twyman.

10 Ibid.

11 Covitz.

12 Sid Bordman, “‘Steve Buzz’s Bomb Act Captures Tigers Again,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1973: 12.

13 Ross.

14 April 2014 interview with Steve Busby, http://clubhouseconversation.com/2014/05/steve-busby/.

15 Ross.

16 Busby interview.

17 Covitz.

18 Busby interview.

19 Covitz.

20 Busby interview.

21 Seattle Mariners relief pitcher John Montague tied the mark in 1977, and David Wells of the New York Yankees broke the record and set a new mark of 38 innings on May 24, 1998. Busby’s USC teammate, Jim Barr, held the National league record of 41 set in 1972 and this wasn’t broken until 2009 by Mark Buehrle. Yusmeirio Petit of the San Francisco Giants set a new record of 46 in 2014.

22 Joe McGuff, “20-Win Champagne Has Flat Taste for Busby,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1974: 22.

23 McGuff, “Player Yelps Following the Bouncing of Lau,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1975: 30.

24 Bordman, “Healy Gets Healthy and So Does Royals Catching,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1975: 14.

25 Ron Fimrite, “Stress, Strain and Pain,” Sports Illustrated, August 14, 1978.

26 Bill Reiter, “Finding Steve Busby,” Kansas City Star, April 1, 2007.

27 McGuff, “Busby, Little Spruce Up Royals’ Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1976: 18.

28 Ibid.

29 McGuff, “Swift Wolhford’s Magic Glove Wows Royals,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1976: 19.

30 “Busby Hurt Again,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1976: 30.

31 “Busby Still a Puzzle,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1976: 24.

32 Ibid.

33 “Royals,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1976: 30.

34 McGuff, “Pitching Shy Royals Storm Heights with Bats,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1976: 13.

35 Fimrite.

36 “Busby Rebuilding Family Life, Career,” Chicago Tribune, April 21, 1978.

37 Covitz.

38 Ibid.

39 Jim Reeves, “Rangers Roundup,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1984: 49.

40 Busby interview.

41 April 2014 interview with Steve Busby, http://clubhouseconversation.com/2014/05/steve-busby/.

42 Bill Reiter, “Finding Steve Busby,” Kansas City Star, April 1, 2007.

43 Ibid.

44 Busby interview.

45 Jim Reagan, “Steve Busby: Locked Into the Job He Loves,” Durant (Oklahoma) Democrat, March 19, 2016.

Full Name

Steven Lee Busby

Born

September 29, 1949 at Burbank, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.