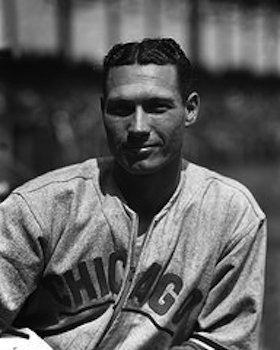

Clay Bryant

Hard-throwing right-hander Clay Bryant went 32-20 in parts of six seasons for the Chicago Cubs before chronic elbow and shoulder pain ended his career at the age of 28 in 1940. But for one summer, the affable Alabaman caught lightning in a bottle. En route to winning 19 games and leading the National League in strikeouts in 1938, Bryant tossed seven consecutive complete games, winning six of them, in the first 25 days in September to help the Cubs erase a nine-game deficit and capture an unlikely pennant.

Hard-throwing right-hander Clay Bryant went 32-20 in parts of six seasons for the Chicago Cubs before chronic elbow and shoulder pain ended his career at the age of 28 in 1940. But for one summer, the affable Alabaman caught lightning in a bottle. En route to winning 19 games and leading the National League in strikeouts in 1938, Bryant tossed seven consecutive complete games, winning six of them, in the first 25 days in September to help the Cubs erase a nine-game deficit and capture an unlikely pennant.

Henry Claiborne Bryant was born on November 16, 1911, in Madison Heights, a small town near Lynchburg in central Virginia.1 By the end of the decade his parents, Alonzo Summerfield and Maude Estelle (Johnson) Bryant, native Virginians, had left behind the rolling hills, pastures, and the family farm, and resettled with their three children, Mary, Norman, and Clay, in the bustling city of Birmingham, Alabama. The elder Bryant found employment as a pipefitter and molder in the booming city, which had seen its population more than quadruple in two decades to about 178,000 in 1920. Birmingham was nicknamed the Pittsburgh of the South and Magic City, and its fortunes and economic growth rested on its steel and iron production. According to various US Census reports, the Bryants lived on 31st Avenue in the heavily industrialized north side of town, where the young Clay attended Acipco elementary school. The name of the school was derived from the American Cast Iron Pipe Company, one of the biggest employers in the city. Bryant reported on a questionnaire from the Baseball Hall of Fame that he completed two years at Paul Hayne High School before dropping out to find work.

It is not surprising that Clay and his brother Norman, just a year older, became interested in baseball. With its competitive semipro and industrial leagues as well professional teams, Birmingham was one of the most renowned cities in the South for baseball, if not the most. The highly regarded and successful Barons, who traced their history back to at least 1901 with the formation of the Class A Southern Association, played their games in Rickwood Field. Located about five miles southwest of the Bryants’ residence, Rickwood Field, built in 1910, was considered among the finest ballparks in the South. The Black Barons of the Negro Leagues also played their games at Rickwood Field and were known to draw as well as their white counterparts.

By the time Clay left school at about the age of 16, he was already an accomplished baseball player. He was known as a hard-throwing right-hander whose strength reportedly came from shoveling slag at a local foundry.2 The annual Magic City League tournaments showcased some of the best talent in the region and attracted scouts from the big leagues and all eight teams in the Southern Association. After the 1929 tournament, Pop Shaw, a scout for the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association, signed the Bryant brothers, as well as teammates Jimmy Densmore and Dee Miles.3

Bryant’s professional baseball career got off to an inauspicious start. As an 18-year-old in 1930 just as the Great Depression tightened its grip on the country, he joined his brother on the Chambersburg (Pennsylvania) Blue Yanks in the Class D Blue Ridge League and also hurled for the Pelicans. Plagued by wildness, the teenager was rarely used (22 walks and 34 hits in just 28 combined innings).

In an exhibition game prior to the 1931 season Bryant suffered an injury that nearly derailed his career and ultimately ended it prematurely. Bryant’s right elbow was fractured when he was hit by a line drive during spring training with the Pelicans. “His year was ruined by a sore arm,” wrote The Sporting News, and he missed the entire season.4

Bryant was back with the Pelicans in spring training in 1932. Sportswriter Val Flanagan reported that the 20-year-old with a “dazzling fast ball” had a “fine chance to make the team.”5 Larry Gilbert, who skippered the Pels from 1923 through 1938 (except in 1932 when he was the team president), was impressed with the stout 6-foot-2, 200-pound Bryant, but also recognized that the green recruit lacked the experience to join a mature club like New Orleans, whose pitchers averaged almost 29 years of age. Splitting his time among two teams in the Class D Mississippi Valley League and another in the Class B Three-I League, Bryant went 6-9, logged 127 innings, and walked 79.

Bryant’s career took off in 1933 after he was optioned to Zanesville, Ohio, in the Middle Atlantic League. A fan favorite, Bryant emerged as one of the best hurlers in the circuit, winning 15 games and posting a sturdy 3.99 ERA in 196 innings to help the Greys capture the league title. Local newspapers played upon his Southern roots and affectionately called him the Colonel, or “cunnel” and “massah” to evoke Bryant’s lazy Southern drawl. Described as possessing “a fine and easy movement on the mound,” the hard-throwing Bryant struck out 171 batters, trailing only teammate Al Milnar.6 More impressive than his pitching was his slugging. Seeing action as a corner outfielder and pinch-hitter, Bryant led the team with a .387 batting average (72-for-186) and a .656 slugging percentage. He belted 12 homers, including three (as well as two singles) in a herculean effort against Dayton on September 7.

Bryant had a championship season in other ways, too. He met local resident Opal Rarick, whom he married on September 26, 1933. The Bryants called Zanesville home until Clay retired from baseball in the mid-1970s. They raised two children: Clay Jr, who pitched for three years in Organized Baseball (1956-1958), making it to class A in the New York Yankees organization; and Chuck Bryant, who played football at Ohio State University and for one year with the St. Louis Cardinals (1962). The elder Bryant was an excellent, all-around athlete, who enjoyed hunting, fishing, and especially basketball. In the offseason he played semipro basketball in a number of different city leagues, including in Zanesville and Birmingham.7

In his fourth spring with the Pelicans, Bryant finally landed a spot with Larry Gilbert’s squad in ’34. The “big smoke ball hurler” was “nursed along,” opined The Sporting News, which also noted that he was a triple threat. “His primary capacity is that of a pitcher,” reported the weekly, “but so well does he do other things, such as hit, field, and run, that he may find himself in the unique position of pitcher-utility man.”8 Fulfilling his promise, Bryant went 16-10 and logged 248 innings, helping the Pelicans capture the league title and the Dixie Series by defeating the San Antonio Missions, champions of the Texas League. Bryant also hit a team-high .327 (36-for-110) and belted four homers, one of which was a dramatic walk-off clout in the 11th inning to preserve his 1-0 shutout against the Little Rock Travelers.9 In August New Orleans, a farm team of the Cleveland Indians, sold Bryant’s contract to the Chicago Cubs.

Following a productive spring at the Cubs’ spring training site on Catalina Island in 1935, Bryant earned a spot on the big-league roster. “[Bryant] is high in favor of Mr. Grimm,” reported Chicago sportswriter Ed Burns.10 Bryant was collared with a loss in his major-league debut, on April 21, after yielding five hits and four runs (three earned) in three innings of relief in a 12-inning, 8-4 setback in Cincinnati. Relegated to the far end of the bench, Bryant picked up his first win by holding the Philadelphia Phillies to three hits and one run in a 6?-inning relief outing in the second game of a doubleheader on June 13. In mid-July the Cubs optioned the struggling right-hander (5.16 ERA in 22? innings) to the Birmingham Barons, where he fared almost as poorly (3-8, 4.91 ERA).

The Cubs had high expectations for Bryant despite his setback in 1935. Ed Burns of the Chicago Tribune reported that Bryant secured the final spot on an eight-man staff in 1936, but his “horribly wild and sloppy exhibitions” on the Cubs’ trek eastward from California tempered Grimm’s expectations.11 While the reigning NL pennant winners battled the New York Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals in a season-long pennant race, Bryant was a mop-up artist, seeing action in 26 games (24 of which were losses) and posting a respectable 3.30 ERA in 57? innings.

“Grimm has given up on his stubborn thought that Clay Bryant is a pitcher of major league talent,” wrote Ed Burns as the Cubs’ spring training came to a close in 1937.12 With a 2-4 record and only 80 innings in two big-league seasons, Bryant’s future was cloudy even with the trade of dependable swingman Roy Henshaw to Brooklyn in December 1936. Clyde Shoun, a 25-year-old southpaw, had supplanted Bryant as the club’s best young prospect. Bryant, once again relegated to mop-up duty, struggled with his control, walking 26 in his first 27 innings (5.67 ERA) and seemed destined to be optioned. Given his first start, on May 31 in the second game of a doubleheader against St. Louis at Sportsman’s Park, Bryant saved his job by tossing a complete-game six-hitter to win his third game of the season. In an unexpected turnaround, he pitched in excess of 22 consecutive scoreless innings during a five-game stretch from May 31 to June 20. Bryant had impressed the Cubs with an “amazing brand of pitching that attracted wide attention during the recent road trip,” wrote Ed Burns glowingly.13 Bryant’s complete-game five-hitter to subdue the Pittsburgh Pirates, 5-1, on August 11 extended the Cubs’ lead over the New York Giants to 6½ games. Bracing for another league title, the Cubs lost 16 of their next 24 games to fall three games off the lead, and ultimately finished in second place, three games behind the Giants. Bryant put an exclamation point on his season by tossing the first of his two career two-hitters and recording his first shutout in a 2-0 whitewashing of the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field on September 28. In what was described by Chicago beat writer Irving Vaughan as a “performance replete with class,” Bryant knocked in a run with a triple and scored the other run.14 A genuine double threat by season’s end, Bryant (9-3, 4.26 ERA in 135? innings) batted .311 (14-for-35).

Bryant “figures heavily in manager Charley Grimm’s plans to construct a pennant-winning staf(sic),” wrote the Chicago Tribune’s Irving Vaughan as the 1938 season got under way.15 Given the start on Opening Day, Bryant was clobbered for eight hits and five runs and lasted just 3? innings against the Cincinnati Reds (though the Cubs won). After picking up his first win on May 12 with a five-hitter with eight walks against Brooklyn, Bryant hurled the two longest games in his career (11? innings of relief against New York and 10? innings against Boston) but lost both in heartbreaking fashion, leading Vaughan to lament that Bryant’s “closest associate is misfortune.”16

On June 19 Bryant notched just his fourth victory by going the distance against the Dodgers in the second game of a doubleheader to commence one of the most improbable runs of a starting pitcher in Cubs history. From June 19 through the remainder of the season, Bryant proved to be one of the best and most durable pitchers in baseball, winning 16 of 22 decisions, starting 22 of 27 appearances, tossing 15 complete games, and posting a robust 2.85 ERA in 192? innings. Among his victories were two three-hitters and a two-hitter. Bryant’s improvement resulted from better control; he had walked 34 batters in 38 innings over his first six appearances in May, but walked only 69 after June 19. Bryant credited longtime New York Yankees infielder Tony Lazzeri, whom the Cubs signed in the offseason, for the improvement. “Lazzeri changed my grip on the ball. I always gripped the ball across the seams,” he said. “I still do but Lazzeri got me to move my grip a little farther around on it. That helped my control a lot. I cut down my fast-ball ‘slides.’ ”17

After plodding through much of the 1938 season, the Cubs caught fire about one month after catcher Gabby Hartnett replaced Charlie Grimm as player-manager. The North Siders won 28 of their final 42 games to capture their fourth pennant in 10 years in stunning fashion. They erased a nine-game deficit in the standings on August 20 and moved into first place on September 28 when Hartnett etched his name in baseball history by walloping the “Homer in the Gloamin’” to defeat Pittsburgh in a game Bryant started. He lasted 5? innings. Prior to the game, the Chicago Tribune reported the Bryant had carried more than his fair share of the pitching burden all season.18 That was an understatement. By that September 28, the 26-year-old hurler was running on fumes. It was his second consecutive start on two days’ rest. From September 1 through September 25, he tossed seven straight complete games, winning six of them, and had pitched four times on three days’ rest. With 19 victories, Bryant trailed only teammates Bill Lee (22) and Cincinnati’s Paul Derringer (21); he also finished third in innings (270?), and paced the NL in strikeouts (135) and walks (125).

As the Cubs prepared to face the heavily favored New York Yankees in the World Series, the worst-kept secret in Chicago was Bryant’s ailing arm. “It might not bother him for one game,” wrote Irving Vaughan, “but he could hardly come back quickly.”19 Tribune sports editor Arch Ward wrote that Bryant’s right arm was so crooked and mangled that it “couldn’t be straightened out.”20 The Yankees beat Lee and Dizzy Dean (manager Hartnett’s unexpected choice to start Game Two) at Wrigley Field in the first two surprisingly competitive World Series games. Bryant started Game Three at Yankee Stadium, on October 8. Well rested, he had pitched only once (three scoreless innings of relief) since Hartnett’s historic homer. Bryant held the vaunted Bronx Bombers hitless for 4? innings before Joe Gordon smashed a home run to deep left field to tie the game, 1-1. The Yankees, who had outscored their opponents by 255 runs during the regular season, picked up their second run three batters later, when Red Rolfe singled to drive in pitcher Monte Pearson. Bryant yielded singles to Joe DiMaggio and Lou Gehrig and a one-out walk to George Selkirk to load the bases. Gordon’s two-run single signaled the end of the day for Bryant, and secured an eventual 5-2 victory. The Yankees’ Red Ruffing hurled his second complete game of the series the following day to hand the North Siders their fourth loss in the fall classic in 10 years.

Bryant was never the same after his overuse in the latter half of 1938. He made only 12 more appearances and won only two more games in the next two years. In his first three starts in 1939, the 27-year-old hurler was clobbered (29 hits and 18 earned runs in 23? innings) before arm pain made pitching impossible. Save for one mound appearance in mid-August, Bryant was confined to pitching batting practice and occasionally pinch-running for Gabby Hartnett. Beat writer Edward Burns described Bryant as a “flop” and noted that “his failure lacked glamour” like the struggles of his teammate Dizzy Dean, whose arms woes limited him to 96? innings. Burns suggested that Bryant’s “troubles never appealed to the public’s imagination” like Dean’s, and consequently Bryant became an object of scorn and derision for the fans.21

Bryant’s relationship with the Cubs reached its nadir in 1940. Team owner Philip K. Wrigley was incensed when the pitcher refused to sign a contract calling for a 40 percent cut from his previous year’s salary, estimated at $15,000. Bryant eventually signed and had an encouraging spring, yet was unable to pitch when the season commenced, once again raising the ire of Wrigley, who openly questioned the pitcher’s motives. In mid-May specialists at John Hopkins hospital determined that not only did Bryant have bone chips in his elbow, he had a severely injured shoulder, the result of pitching with an unnatural motion and favoring his elbow since being hit by a pitch in 1931.22 Unexpectedly, Wrigley refused to pay for Bryant’s medical expenses to see a specialist in Los Angeles, and suspended the player indefinitely in early June.23 Bryant’s inability to pitch, suggested the Chicago Tribune, was “more of a mental hazard than serious arm ailment.”24 Bryant appealed to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, but was summarily rejected. In a final, bizarre twist, Wrigley settled with Bryant by upholding the suspension, but hiring his wife, Opal, for a salary of $50 per week over four weeks so she could monitor her husband’s rehabilitation in Los Angeles.25 Bryant returned in August to make his final eight, mostly ineffective appearances in a big-league uniform.

The Cubs cut their ties to Bryant in 1941 when they optioned him to Tulsa of the Class A1 Texas League in late March. “Bryant presents one of the most unusual cases of player psychology to appear on the Cubs,” opined the Chicago Tribune in a scathing report. “In an apparent effort to protect his own professional interests he has done just about everything conceivable to destroy his major league career.”26 Bryant logged just 60 painful innings for the Oilers. In the offseason he underwent an operation to remove bone chips in his elbow. He recovered enough to make nine starts with his hometown Zanesville Cubs of the Class D Middle Atlantic League in 1942. Just 30 years old, Bryant called it quits in late August when Zanesville traded him to Macon in the Sally League. In parts of six big-league seasons, Bryant went 32-20 and carved out a 3.73 ERA in 543? innings. He batted .266 (51-for-192).

After a year away from baseball, Bryant began the second phase of his baseball career in 1944 when he was named manager of the Newark Moundsmen in the inaugural season of the Class D Ohio State League. After capturing the league title in his rookie season, Bryant moved to the Dodgers organization in 1945, and established a reputation as a tireless and committed teacher to young prospects. He managed 10 different teams from 1945 to 1964, the majority of those on the Double-A and Triple-A level, and won five league championships. His footprint extended to seemingly everyone who passed through the Dodgers’ farm system during the club’s heyday. Bryant’s importance as a mentor may have been a reason why he never landed a big-league manager’s job. In 1954 the Dodgers chose Walter Alston over Bryant to pilot the club. “The real story,” wrote sportswriter Ken Goekins, “is that Bryant was just too good in his job of teaching young ballplayers how to become major leaguers.”27 Bryant finally made it back into a big-league dugout in 1961 when he was on Alston’s staff for a season. Bryant spent his last decade in baseball in the Cleveland Indians organization. He was on the Indians’ coaching staff in 1967 to 1974, managed several minor-league teams, and also served as a roving pitching instructor.

After Bryant retired, he and his wife, Opal, resided in Ohio, and later moved to Florida. Bryant died on April 9, 1999, at the age of 87 at Hospice by the Sea in Boca Raton. He was survived by his wife and two sons.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted:

SABR.org.

Clay Bryant player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 According to Baseball-Reference.com, Bryant was born on November 26; however, his date of birth was November 16 according to the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) and the U.S. Public Records Index, Vol. 2.

2 Franklin (Indiana) Evening Star , May 23, 1939, 4.

3 The Sporting News, January 9, 1936, 3.

4 The Sporting News, February 25, 1932, 2.

5 Ibid.

6 “Introducing the Greys, Clay Bryant,” Times Recorder (Zanesville, Ohio), April 27, 1933, 16; “Milnar and Hass Equal in Won-and-Lost Percentage,” Times Recorder, September 8, 1933, 12.

7 Bryant played for the Cumberland Bulldogs in Zanesville. “Join Bulldog Team,” Times Recorder (Zanesville, Ohio), November 24, 1933, 7.

8 The Sporting News, April 19, 1934, 2.

9 “Pelican Hurler Has Great Day,” Courier News (Blytheville, Arkansas), July 19, 1934, 8.

10 The Sporting News, March 28, 1935, 1.

11 The Sporting News, April 9, 1936, 8.

12 The Sporting News, April 22, 1937, 1.

13 Ed Burns, “Cubs Take First Place, Giants Get Berger,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1937, 21.

14 Irving Vaughan, “Bryant Shuts Outs Reds On 2 Hits,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1937, 19.

15 Irving Vaughan, “Pound Brown Pitchers Fourteen Hits,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1938, B1.

16 Irving Vaughan, “Shoffner Hits With Two On To Defeat Bryant,” Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1938, 19.

17 Bill McCullough, “Bryant Traces Climb To Fame To Lazzeri Tip,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 13, 1939.

18 “Bryant Opposes Klinger in Today’s Pirate Game,” Chicago Tribune, September 28, 1938, 1.

19 Irving Vaughan, “Yankee Sluggers Show Punch in Practice,” Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1938, 19.

20 Arch Ward, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1938, 23.

21 The Sporting News, December 28, 1939, 1.

22 The Sporting News, May 30, 1940, 10.

23 “Bryant Loses Appeal to Cubs; May See Landis,” Chicago Tribune, June 6, 1940, 39.

24 “Wrigley Settles $50 Weekly On Ailing Bryant,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1940, C1.

25 Ibid.

26 “Bryant Irks His Boss Once too Often,” Chicago Tribune, March 30, 1941, D1.

27 Ken Goekins, “Alston Passes Another Milestone,” Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, May 7, 1971, 4-B.

Full Name

Claiborne Henry Bryant

Born

November 16, 1911 at Madison Heights, VA (USA)

Died

April 9, 1999 at Boca Raton, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.