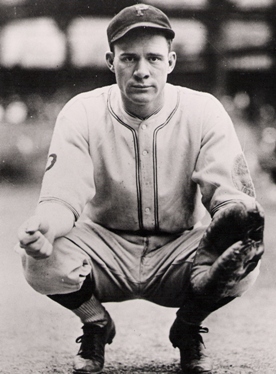

Johnny Gooch

There have been three Gooches in major-league history, and at least another eight in the minors. The Gooch considered here is John Beverley Gooch, who played 805 games over the course of 11 seasons (1921-30; 1933), batting .280 with just seven homers while driving in 293 runs. His younger first cousin Charlie appeared in 39 games for the 1929 Senators. The apparently unrelated Lee Gooch appeared in two games with the 1915 Indians and 17 with the 1917 Athletics.

There have been three Gooches in major-league history, and at least another eight in the minors. The Gooch considered here is John Beverley Gooch, who played 805 games over the course of 11 seasons (1921-30; 1933), batting .280 with just seven homers while driving in 293 runs. His younger first cousin Charlie appeared in 39 games for the 1929 Senators. The apparently unrelated Lee Gooch appeared in two games with the 1915 Indians and 17 with the 1917 Athletics.

Johnny Gooch was born in Smyrna, Tennessee, on November 9, 1897, the son of George and Mary Gooch, who farmed in Smyrna. Charlie was born there on June 5, 1902. Johnny received his high school diploma from the private Wallace University School in Nashville. He was captain of the baseball team all four years at Wallace.[1] He then stepped up to semipro in 1914 with the Old Anchor Spring Mattress team.

Johnny started his professional career as a catcher (5’ 11 1/2” and 175 pounds) in 1916. He had started with Nashville of the Southern Association, but because of his youth, the Volunteers sent him to Talladega in the Class D Georgia-Alabama League.[2] His work for the Tigers wasn’t that outstanding, but not unusual for a catcher of the era – a .177 average in 70 games. During 1917 and 1918, he didn’t play organized ball but instead returned to the family farm to help his parents. His oldest brother had drowned and the next oldest brother, George Jr., had gone off to World War I. Johnny himself was called and on a train heading to the service when news of the Armistice broke and the train returned to Nashville.

In 1918, Johnny met his future wife, Mary Virginia Omohundro. Early the next year, he went to New Orleans and played baseball for Elmer Candy, a company team which played on Sundays in an independent winter league. During the week he worked as a carpenter on boats in dock at New Orleans. That spring he tried out with the New Orleans Pelicans and made himself useful “throwing and chasing balls for the pitchers to practice with – he was told to ‘go away’ as they didn’t need him, but he showed up every day anyway.”[3] The Pelicans reportedly finally signed him to a contract, and he was sent to Cleveland, and then to Mobile, where he was released as not up to their standards. When Birmingham had played Mobile, though, he’d been noticed for his dedication, “so anxious he seldom left the park.”[4] An accident deprived Birmingham’s affiliated Newport News club of a catcher. The Barons’ manager, Carlton Molesworth, remembered Johnny, and wired Mobile as to how to reach him.[5]

He ultimately played with three clubs in 1919 – the Newport News Shipbuilders, the Atlanta Crackers, and the Birmingham Barons. He hit .202 for the Class C Virginia League team, but once he reached Class A, playing in the Southern Association with Atlanta and Birmingham, he blossomed, batting .277 for the two teams combined (albeit over just 47 at-bats.)

Before either Johnny or Charlie reached the big leagues, the 1920 census found them sharing quarters in a boarding house in Birmingham. Charlie was working as a mechanic in an auto shop and Johnny was a draftsman working in the shipyards – but he was in Alabama for baseball. Two years later, Charlie embarked upon a 10-year minor league career as an infielder. Johnny played the full 1920 season with the Barons, got into 69 games, and hit .217. The next year, again with Birmingham, he broke out, batting .288 in 136 games. He also became close with future Pirates star Pie Traynor. Although the roommates could never agree on whether to keep the window shade up or down, the friendship endured for the rest of their lives.[6]

That September he got his first crack at big-league baseball with the Pittsburgh Pirates in September. [7] In his second game in the majors, he caught former Birmingham batterymate Johnny Morrison’s shutout of the Cubs. He batted eighth and had two hits in three times at-bat, driving in one of eight Pirates runs; “his batting was hard and timely,” wrote the Washington Post. (He’d appeared briefly on September 9, but saw no action on offense.) After 13 appearances, hitting .237 with three RBIs, his first season was over. It would be 11 years before he played in the minor leagues again.

The Pittsburgh Press touted the switch-hitting Gooch as “one of the smartest and most active catchers to break into the big show in years” and “perpetual motion itself.”[8] He became Pittsburgh’s primary catcher in 1922, as the veteran Walter Schmidt held out and did not play until August. Johnny enjoyed his best season in the majors with a .329 batting average, scoring a personal-best 45 runs, a figure he never approached in later years. He drove in 42 in his 105 games, which he met or exceeded twice later.

Johnny “was a popular figure among the Forbes Field faithful, partly because he had a fun name. When Gooch stepped to the plate, public address announcer Nat Moll bellowed, ‘Johnny Goooooooch,’ and Pirates fans replied in kind.”[9] Though he was good at the bat, his defense was not prized. The Christian Science Monitor called him “a bright prospect and all that, but absolutely without knowledge of the batters of the league. He is a good hitter, but had trouble last fall in getting back to the stand after fouls.”[10] That November, Johnny and Mary Omohundro got married.

Gooch continued to share catching duties with Schmidt in 1923 (when his average dipped to .277) and 1924 (climbing back to .290). He appeared in 66 and 70 games, respectively. Part of the time he lost in 1924 was due to injury. He’d missed the second half of August in 1923 and a good chunk of September in 1924. He was a little too high-strung at times, perhaps, and was suspended for improper language after a May 1924 confrontation with an umpire in a game against the Braves in Pittsburgh, but didn’t miss too many games. The Pirates finished third in 1924, three games out of first.

In 1925, another veteran catcher – Earl Smith, who’d begun his career with the Giants and who’d caught 35 games in 1924 – became the first-stringer for Pittsburgh, appearing in 109 games (batting .313). Gooch caught in 79 (hitting .298), often finishing games Smith had started.

On August 28, 1925, the Gooches welcomed their first child, John Claiborne Gooch. Both September and October were thrilling months, too. The Pirates clinched the pennant in September, finishing 8 1/2 games ahead of the Giants, and they faced off in the World Series in October against the Washington Senators. Gooch’s defense had apparently improved. In doping the Series, A. M. Elias wrote, “As a fielder, Gooch is rated the superior of Smith by National League critics, and one of the best maskmen in the older league.”[11] Little John Gooch, nicknamed “Skippy,” was declared the official mascot of the Pirates for the World Series. Johnny pushed Skippy around the bases in a baby carriage prior to the first game of the Fall Classic. The same carriage was used by two later family arrivals – Beverley Randolph Gooch (1932) and Mary Virginia Gooch (1935).

Gooch appeared in three of the seven games, appearing twice after Smith had been replaced by a pinch-runner, and starting just once, in Game Four. He was 0-for-3 at the plate, while Smith hit .350. Yet when the Pirates beat the Senators, four games to three, Gooch was still counted as one of the World Champions. After the Series was over, Gooch returned to his wintertime work as an automobile salesman near his home in Tennessee.[12]

The Pirates kept much of the same lineup in 1926, hoping to repeat, but it’s never that easy. They finished in third, 4 1/2 games behind the Cardinals. Gooch continued to spell Smith frequently, appearing in 86 games (80 behind the plate) to Smith’s 105 (he caught in 98). His hitting dropped to .271, though he drove in 42. He only scored 19 runs, though.

Pittsburgh went to another World Series in 1927. Gooch caught 91 games, seeing more duty as Earl Smith drew a 30-day suspension in mid-June.[13] While his average slipped again, to .258, his RBI total climbed to 48 and he drew praise for his throwing. Also of interest that year was how Johnny circulated a petition asking for the reinstatement of his roommate, star outfielder Kiki Cuyler, after manager Donie Bush benched Cuyler for several weeks late that season.[14]

In the Series, he appeared once again in three games. The Yankees swept this one in four games – this was 1927, remember. Gooch had six plate appearances and walked once (Earl Smith was 0-for-8). Though the outcome was probably a foregone conclusion, the Series ended in the bottom of the ninth on a wild pitch by Johnny Miljus. Rather than see his pitcher be branded as the goat, Gooch spoke up right away and said the ball was not a wild pitch but should have been scored a passed ball, and that it was on his shoulders. “Nine times out of 10 I would have caught it, but I was down on the ground and the ball went a little high and wide. That ball should have been caught. The official scorer made a mistake. It was no wild pitch. The error should have been charged against me.”[15] Memories may have become distorted at a distance, but 16 years later, Arthur Daley wrote in the New York Times that Miljus’s pitch was “the wildest wild pitch that mortal man ever uncorked.”[16]

Spitballers were on the way out, the only remaining ones being those who’d been grandfathered in before the pitch was banned in 1920. When one of them, Burleigh Grimes, joined the Pirates in 1928, Gooch was asked to be Grimes’s personal catcher. Gooch was back to being second-string to Earl Smith, though they split the business until June 8, when Gooch and Joe Harris were traded to Brooklyn for catcher Charlie Hargreaves, who was the steady starter from that time on. Grimes won 25 games, to lead the league. Gooch had appeared in 31 games and was in the hitting doldrums (.238), but – even though Harris was the key to the trade in Brooklyn’s eyes – Gooch suddenly hit .317 in the 42 games he played for the Robins. His season ended a bit early when he broke three ribs in a September 24 collision with Frankie Frisch.

Gooch did not enjoy his time in Brooklyn very much, as evidenced by one story that was often retold in future years. An argument arose (the accounts vary as to which player) over a ball-strike call with veteran home plate umpire Bill Klem. Klem supposedly left it to Johnny to second him about whether the pitch was over the plate, but Johnny retorted, “Alibi your own rotten decisions, I’ve got troubles of my own.”[17]

The following April he was traded on Opening Day to the Cincinnati Reds for Val Picinich, who’d held out and refused to sign a contract with Cincinnati. Gooch later explained that he’d had his own salary disagreements with Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss, which he believed had made him persona non grata with other clubs.[18] Rube Ehrhardt was the key part of the deal, joining Gooch in departing Brooklyn. Johnny had managed one at-bat before the trade, but made an out. With the Reds he came to the plate 313 times and hit for an even .300 average. That may have seemed like a nice way to end a career; he announced in early October that he’d accepted a business position and was retiring from the game. The way Johnny told it, he may have been traded because Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson was a little too sensitive. “If there was anything he didn’t appreciate,” Gooch was quoted as saying, “it was a laugh. He said something wild one day and I laughed. He pointed to me and told one of the coaches, ‘That’s enough of him.’ Four days later, I was with the Reds.”[19]

Though he may have laughed at the wrong time, in general he was “a big burly fellow, short on conversation and long on action.”[20] He was also the “champion tobacco chewer of all time.” After June 1929, for a couple of years Gooch began drinking, as he and his wife had suffered the loss of their three-year-old son, Skippy, who had fallen and hurt his chin. He was given a tetanus shot, but the shot produced what proved a fatal reaction. Gooch raced home by airplane but arrived too late to see his boy before he died.

Despite the announced retirement, Gooch came back and got just about as much playing time in 1930, but his average was just .243. The Reds put him on waivers at the end of the year. As a 10-year-veteran, he’d have to approve any move to send him to the minors. It appeared that no one wanted him, and he was apparently unwilling to take a trade to a minor-league club. That changed in January 1931, when Cincinnati traded him to the Baltimore Orioles in the International League, but in March, Commissioner Landis canceled the deal. Then, on May 1, Judge Landis put Gooch on the ineligible list for failure to report to the Reds! He never played ball in 1931.

In January 1932, Johnny asked to be reinstated; on the 18th he was traded to Nashville in the Southern Association for Joe Cicero. There he played 117 games and hit .334, showing he still had it with the bat and behind the plate (he only committed eight errors.) After the season, the Boston Red Sox sought him out and reached terms with Nashville. He joined Boston for spring training in Sarasota in 1933.

In camp, Gooch “reflected a change of attitude. He told sportswriter Jack Malaney that “‘whereas a quart a day used to be my usual portion,’ he hadn’t taken a drink in over two years.”[21] Johnny and Mary always said that when it was known she was pregnant with their second child (May 1931), he stopped drinking and never touched another drop of alcohol in any form after that. It was reinforced when the second child, Beverley, arrived on January 31, 1932 – a boy with auburn hair like Skippy and Johnny.

The veteran praised Boston’s pitching staff, but he didn’t get to play much for manager Marty McManus, particularly after the Sox made a move and traded for Rick Ferrell on May 9. Gooch was hitting .091 at the time. He doubled that by the end of the year, to .182, in 37 games. His final big-league game was on September 12, 1933.

Gooch was in three different farm systems the next three years:

1934: with Columbus, hitting .177 in 39 games in the Cardinals’ chain

1935: back in Nashville (a Giants farm club), where he hit .226

1936: in Class B ball with the Durham Bulls, in the Cincinnati system again; he hit much better (.282) at the lower level of play.

Gooch also managed Durham, and pitched five innings at one point during the season. The Bulls finished second in the Piedmont League. An amusing anecdote from that season was told by Johnny Vander Meer, who would go on to “Double No-Hit” fame two years later. Vander Meer was walking a lot of men, but he was missing the plate by just a few inches most of the time. So he, skipper Gooch, and the groundskeeper would dig up home plate under cover of darkness and shift it ahead of the days Vander Meer pitched.[22] The story was prompted by Johnny’s close friend, Nashville Banner sportswriter Fred Russell. Gooch’s daughter Virginia said, “He had funnies about Dad in several of his books – whether all the things he said were true or not, only Dad knew for sure, but they were great practical jokers and people never knew when either was serious for sure.”

In January 1937 – thanks to Pie Traynor, who had become manager in 1934 – he signed on as pitching coach for the Pittsburgh Pirates.[23] Some players apparently urged Traynor to put Johnny in the lineup late in the season, but it didn’t happen.[24] Gooch coached three full years, back with the team where he’d first broken in. A number of news stories of the day raved about his success coaching for the Bucs. A column by Lester Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press in 1938 quoted Traynor: “There is one of the smartest handlers of pitchers in the National League.”[25]

The Sporting News said, in Gooch’s obituary, that he coached with the Pirates in 1940 as well, but also said he managed in Mt. Airy at one point. The one year for which SABR records don’t show a manager in Mt. Airy was 1940. An Associated Press dispatch dated October 17, 1939 details his appointment as a scout covering the Southern states for Pittsburgh. In particular, he focused on his home base, Nashville. A news story from September 5 headlined “Johnny Gooch Victimized” mentions the Pirates scout. It told how some fans in Bristol let the air out of the tires of a car they thought was that evening’s umpire, only to see the umpires get into another vehicle and Gooch perhaps no longer in a mood to write up any favorable evaluations of Bristol ballplayers. [26]

Johnny signed on to manage the Hutchinson Pirates in the Western Association for 1941. He played in 40 games, too, and hit .325, but the team finished next-to-last, 40 games out of first. His last year in the game was 1942, managing the Bluefield Blue-Grays in the Mountain State League. Johnny was 44 but still put himself into 14 games and got his last 10 hits (in 37 at-bats.) This team finished next-to-last, too. According to family history, his entire team was lost to the draft amid World War II.

An April 1943 report said he had signed with the Springfield Nationals for 1943, but the deal hadn’t suited him. Two months later, a news notice found him living in Nashville and manufacturing baseball bats with the Gooch Manufacturing Company. [27]

After a major fire in 1947, he rebuilt the bat factory, but it caught fire again later that year, and he quit the effort. In the 1950s, he established his own company, also in the woodworking field. He became owner and president of the Gooch Lamp Company (based in the Nashville suburb of Brentwood), which he ran until his death.

In February 1972, Johnny Gooch was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame. A few years later, on May 15, 1975, he died in Nashville. The cause was emphysema, brought on by smoking cigarettes (his daughter says that he even inhaled cigars in his latter years). He was 77.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted below, the author also accessed Gooch’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Rory Costello added a considerable amount of material, and connected the author with Johnny Gooch’s daughter, Virginia Gooch Watson. Virginia read a couple of draft versions of this biography and contributed extensively to this final rendition.

[1] Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Volume LVI, no.1, Spring 1997, article by Ridley Wills, II, pp. 56-69; Batts, William O., Private Preparatory Schools for Boys in Tennessee, c. 1967, pp. 9, 51.

[2] “Gooch A Sure Comer.” Pittsburgh Press, February 12, 1922: Sports-1.

[3] Correspondence from Virginia Gooch Watson, October 31, 2010. A great deal of the information contained here draws upon a detailed biographical sketch which Gooch’s wife wrote in May 1967 and which Johnny himself reviewed and corrected at the time.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Forr, James. Pie Traynor: A Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2010: 44.

[7] His contract was sold for a reported $14,000, a record in the Southern Association at the time.

[8] “Gooch A Sure Comer.”

[9] Ibid., loc. cit.

[10] Christian Science Monitor, April 11, 1922

[11] Hartford Courant, September 30, 1925

[12] Boston Globe, October 17, 1925

[13] Wollen, Lou. “Johnny Gooch Shows Fine Form Behind Plate.” Pittsburgh Press, August 2, 1927: 28.

[14] Russell, Fred. “Why Cuyler Was Benched.” Baseball Digest, May 1968: 48.

[15] Chicago Tribune, October 11, 1927

[16] New York Times, October 3, 1943

[17] “Gooch Tired of Game.” Pittsburgh Press, January 8, 1929: 36. Later anthologized in Lore and Legends of Baseball and Great Sports Humor, by Mac Davis.

[18] Unattributed June 21, 1928 article by Ralph S. Davis in Gooch’s player file at the Hall of Fame

[19] The Sporting News, May 31, 1975. Gooch later added, “It was suicide to laugh.”

[20] Unattributed clipping found in Gooch’s player file

[21] LaHurd. Spring Training in Sarasota. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2006: 52.

[22] “Case of the Traveling Home Plate.” Baseball Digest, May 1959: 32.

[23] Forr, op. cit., loc. cit.

[24] Ibid.: 168.

[25] Unattributed clipping found in Gooch’s player file

[26] Unattributed clipping found in Gooch’s player file

[27] Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1943. It is worth noting that Hillerich & Bradsby, the Louisville Slugger company, turned to manufacturing rifle stocks and other military goods during World War II – though it did continue to produce bats for servicemen.

Full Name

John Beverley Gooch

Born

November 9, 1897 at Smyrna, TN (USA)

Died

May 15, 1975 at Nashville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.