Charles Parks

World War II ended when the Axis powers surrendered to the Allied powers in 1945. Men and women of the U.S. Armed Forces returned to an America deeply affected by years of war, and they sought to resume a simple, more pedestrian way of life. They looked to an America which embraced enterprise and entertainment, and which boasted a national pastime — baseball. While the game had retained its role as a diversion during the war, revitalization commenced with the return of players to the white major leagues and the Negro Leagues. Alongside the many stars who picked up their careers again were lesser-known players such as Charlie Parks of the Newark Eagles.

World War II ended when the Axis powers surrendered to the Allied powers in 1945. Men and women of the U.S. Armed Forces returned to an America deeply affected by years of war, and they sought to resume a simple, more pedestrian way of life. They looked to an America which embraced enterprise and entertainment, and which boasted a national pastime — baseball. While the game had retained its role as a diversion during the war, revitalization commenced with the return of players to the white major leagues and the Negro Leagues. Alongside the many stars who picked up their careers again were lesser-known players such as Charlie Parks of the Newark Eagles.

Charles “Charlie” Ederson Parks was born on June 19, 1917 in Chester, South Carolina, approximately 60 miles north of Columbia.1 He was the oldest of four children born to Sanders and Maggie [Woods] Parks, which included two brothers, George and Isiah, and one sister, Sadie Bell. Sanders’ World War I draft registration card indicates his trade as farming, and his employer as Mr. Lee Carter.2 Maggie, born in Chester, was one of eight children. By 1920, her name does not appear as a member of the family in that year’s federal census; the exact year she married Sanders is not clear, but she did work as a homemaker.3

Chester, a one-time booming cotton and textile region, alternated between economic prosperity and desperate poverty. As the nation entered into the Great Depression, around 1929 when Charles was 12, the Parks family moved to Charlotte, North Carolina area 50 miles northeast of Chester where jobs were more plentiful. While other cities experienced little economic development at this time, Charlotte, as a railway system hub, presented employment opportunities and saw a 22% increase in population between 1930 and 1940.4 Sanders found work as a laborer for the railroad system, and Charles and his siblings were raised there. They attended the Morgan School in the Cherry Neighborhood, Grier Heights/Griertown, of Charlotte. Grier Heights, named for well-respected funeral home director Arthur Samuel Grier, had been formed as a farm community in 1886 by former slaves.5

Neither the origins of Parks’ involvement in baseball nor the beginnings of his professional career are known. He most likely played ball as a child in South Carolina and later as a young adult in one or more of North Carolina’s baseball-rich communities:

“Years before the establishment of national baseball leagues for black competitors in the 1920s, African American men were playing baseball all over North Carolina, from Wilmington to Asheville. Black-owned ball clubs played at a high level, supported by a growing black business class…Baseball teams offered a means of extra income for players as young as 14. Many North Carolina boys left school around that age to work in fields and help support their families. Those who played well might earn the attention of bigger teams. In addition, teams such as the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles and Schenectady Mohawk Giants spent spring training in North Carolina in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Their owners could scout the rosters of North Carolina semipro opponents and take the best players back north with them.”6

It is possible he encountered or even played with men such as Tom Alston, Charlie Neal, and Buck Leonard and, by the age of 21, it must have been clear that Parks had a true talent for the game. He began a professional career in the Negro National League with the New York Black Yankees in 1938, who had Walter Cannady, a third baseman, as player-manager. Parks played in one game, had one plate appearance, and no hits; his name appears on the roster as a relief pitcher. He returned to the New York Black Yankees in 1939; however, this time, his position was designated as catcher. He appeared in two games, had eight plate appearances, and garnered one hit. His manager at this time was George Scales, who also played third base.

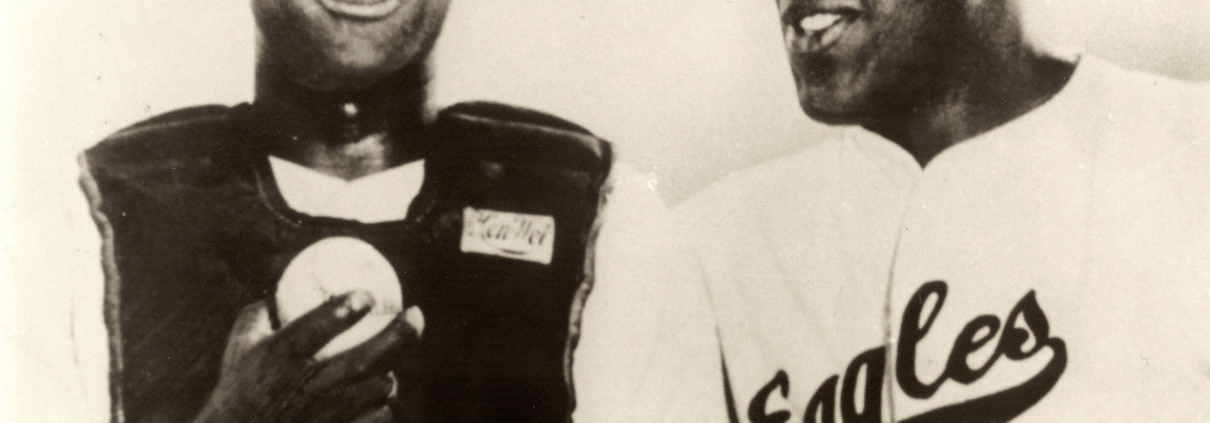

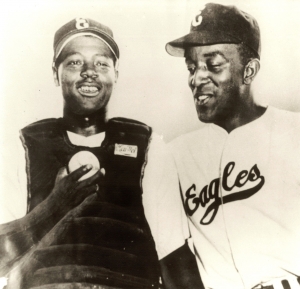

Entering the 1940 season, Parks played for the Baltimore Elite Giants. He shared catching duties with two other catchers, including Roy Campanella, who played the majority of the games. Parks and catcher Ziggy Marcell each appeared in one game, each had three plate appearances, and each had one hit while working under yet another player-manager/third baseman, Felton Snow. Parks did not stay with the Elite Giants the entire season as the next and most significant step in his career took him to the Newark Eagles. There he joined a star-studded cast that included Monte Irvin, Max Manning, Mule Suttles, and catcher Biz Mackey, who assumed the role as player-manager toward the end of the season, replacing manager Dick Lundy. This was certainly good fortune for Parks as he became Mackey’s “understudy.”7 As the season progressed, it was reported that Biz Mackey “has been doing most of the catching for the Eagles this season, sharing the assignment with Charley Parks.”8 In 1940, Parks, who was then 23 years old, appeared in 14 games and had a .154 batting average in 30 plate appearances with the Eagles. Later that year, on October 16, he registered for the military draft as the United States’ entry into World War II seemed imminent.9

Prior to the start of the 1941 season, Parks and his siblings lost their mother, Maggie, at 40 years of age to ovarian cancer on January 15.10 Nonetheless, he returned to Newark, where Biz Mackey, now 43 and still the player-manager, began to reduce his own playing time. Thus, Parks had more opportunity behind the plate; he appeared in 24 games, had 77 at-bats, and compiled a .246 batting average. He also earned recognition by exhibiting his throwing skill at the “John Borican Day” festivities at Newark’s Ruppert Stadium on August 31, 1941; Borican was a “black track star from nearby Bridgeton, New Jersey who held six world records.”11 “Leon Day copped honors in the 100 yard dash…while Monte Irvin took honors in the outfielders’ throwing test and Charlie Parks was adjudged winner of the catchers’ accuracy contest throwing to second base.”12

The 1942 season with the Eagles proved to be Parks’ best as he caught in 41 games and hit .278 in 143 plate appearances. However, U.S. involvement in World War II had intensified, and Parks was called to military service on October 29, 1942. His tour of duty included training at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina and then active duty in European Theater Operations (ETO). He may have played baseball while in the military, either at Ft. Bragg or even abroad in Europe. According to his obituary in the Charlotte Observer of September 19, 1987, “While in the Army, he earned the rank of sergeant. He received the Bronze Star for bravery when his commander was wounded in a battle. Mr. Parks took command and led his company over open ground in the face of enemy automatic fire, capturing a number of the enemy.”13 James A. Riley, in The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, states that “he served three years in the Army, winning three Bronze Stars and being discharged with the rank of sergeant.”14

Both of Parks’ brothers registered for the draft. Isiah, who was seven years younger than Charlie and was unmarried at the time, served in the Army for three years. George, who was five years younger than Charlie and had a wife named Verlee, did not enter into military service.15 Sadly, George and Verlee lost their infant daughter, Alicia Maye, in October 1942. Parks’ sister, Sadie Bell, apparently remained with their father Sanders in Charlotte, North Carolina. Isiah, as did Charlie, reached the rank of sergeant in the U.S. Army, and was awarded the Bronze Star.16

Charlie Parks was discharged from the U.S. Army on February 4, 1946, in time for that year’s Negro National League season. Also discharged in February 1946 was teammate Leon Day, a star pitcher. On Opening Day — May 6 — the battery of Day and Parks led the Eagles to a no-hit shutout of the Philadelphia Stars. It was the start of an amazing season in which the Eagles, with an overall record of 56-25-3, won the Negro League World Series. Parks, age 29, completed that regular season with a .247 batting average in 100 plate appearances over 32 games. The Eagles defeated the Kansas City Monarchs in a tightly-contested seven-game World Series. Parks’ role was restricted to two games and one hitless plate appearance. He played first base while 34-year-old Leon Ruffin assumed the catching responsibilities in each of the seven games. In 1947, Parks, who had earned nicknames “John” and “Hunkie” while playing for Newark, “ended his career with the Eagles as he had started, by sharing the catching duties with Biz Mackey, while batting .287 in his final year.”17

With 1948 came the end of Charlie’s career in the Negro National League. Tragically, that same year, he experienced another loss as his younger brother George, a “prize fighter,” died at the age of 26 due to a cerebral hemorrhage cause by malignant hypertension.18 George left behind his wife Verlee, his father, and his two siblings.

At some point, perhaps prior to his time in the Negro National League, Parks had married Clister Walker. He and Clister, who was eight years older, had a daughter, Virginia.Parks also raised a stepson, John Jackson, who was presumably from his wife’s previous marriage.19

After his career in the Negro National League was over, Parks returned to North Carolina where he maintained his connection to baseball as a player and manager. In July 1948 the Greensboro Daily News reported, “Goshen’s Redwings launch the second half of their season in the Negro American Association at Memorial Stadium tonight…The Redwings are playing under a new manager, Catcher Charlie Parks, who was secured from the Newark Eagles.”20 Later that season, the Asbury Park Press noted, “The Red Wings, managed by Charlie Parks, former Newark Eagle catcher, finished in the first division during the first half of the Southern association race…Parks will do the catching and will bat sixth…” His .333 average is second only to “center fielder David Sims, who is clipping the ball at a .342 gait.”21 Parks’ team travelled outside of North Carolina as well as the Hartford Courant wrote, “The Greensboro, NC Red Wings, members of the Negro Southern American Association, will make an appearance at Bulkeley Stadium today to face the Hartford Indians…[the Red Wings] boast three .300 hitters…Centerfielder, David Sims at .342, Rightfielder Joe Siddle at .315, and Manager-catcher Charles Parks at.333.”22

Parks extended his career in baseball in 1949. At the outset of the season, the Asheville Citizen-Times remarked, “One of the outstanding additions of the [Asheville] Blue’s roster his season is Charles “Hunkie” Parks. Parks caught for Greensboro last season and was considered the best catcher in the league…Parks, who caught for the Newark Eagles for three years, is an aggressive type of player and is expected to add much to the offensive of the Blues this season.”23 Shortly thereafter, the same newspaper noted that “Charles Parks, team captain will be in charge of the Blues until Manager [Robert] Bowman reports.”24

Whether or not Parks participated in baseball on any level for his remaining years is not clear. However, by 1953, he had shifted from the baseball field to work as a machine operator for the Ray Construction Company in Charlotte, North Carolina. He remained in that company’s employ for 20 years, until he retired in 1980. In 1955, he returned, with his wife, Clister, to the Griertown community, where the couple lived until his death on September 13, 1987, at the age of 70. Parks passed away at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina. Clister said that he “was very well-liked in the community… [and] was a very loving hard-working person.”25 After a funeral service at the Little Rock African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church in Charlotte, Charles was interred at the Beatties Ford Memorial Garden Cemetery in Huntersville, which is part of the greater Charlotte metropolitan area. In addition to his wife, he was survived by “his daughter Virginia Gaston; his brother Issac [Isiah] Parks; sister, Mrs. Sadie Holley of Baltimore; foster son, John Jackson; one grandson; five great-grandchildren; and one great-great grandchild.” Clister remained active in the Little Rock AME Zion Church and died 13 years later, at the age of 91, on February 1, 2001; she also was interred at the Beatties Ford Memorial Garden Cemetery.

In a career shortened by two years due to military service, Parks appeared in 117 games and compiled a .257 batting average. In addition to his NNL career with Newark, in 1943 he joined the NNL All Stars, one of four teams which made up the “Independent Clubs.” Other teams included the Atlanta Black Crackers, the South All Stars, and the North All Stars. Parks shared catching duties with Bill “Ready” Cash, on this team managed by Goose Curry; in a series of three games, he appeared in one game and had two hits. Parks’ obituary in the Charlotte Observer summed up his career by noting that he was “a catcher for the Newark Eagles in the Old Negro Baseball League,” was “known for his strong throwing arm and powerful bat,” and that he had “played with some of the greats who went on to break the color barrier in major-league baseball.”26

Sources

For Negro League statistics, the author largely relied on the Seamheads database at www.seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Parks middle name also appears as Edison; however, his World War II draft card signature indicates Edison. Charles was also known as Charlie or Charley.

2 Sanders’ name also appears as Saunders. Isiah Parks’ name also appears as Isiah and Isaac. “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 for Sanders Parks. Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/6482/005152293_05332?pid=24151322&backurl=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv%3D1%26dbid%3D6482%26h%3D24151322%26tid%3D%26pid%3D%26usePUB%3Dtrue%26_phsrc%3DROA234%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=ROA234&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true.

3 “George Woods in the 1920 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=6061&h=42988772&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=ROA253&_phstart=successSource.

4 Dr. Thomas W. Hanchett, “The Growth of Charlotte: A History.” http://www.cmhpf.org/educhargrowth.htm.

5 http://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/special-reports/myers-park/article9087020.html.

6 Bijan C. Bayne, “Early Black Baseball in North Carolina,” Tar Heel Junior Historian, 51:1 (fall 2011), https://www.nclor.org/nclorprod/file/edbef9bd-2dea-457d-8daf-25eb1cfdc616/1/f11_black_baseball.pdf

7 Alfred M. Martin and Alfred J. Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey: A History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Publishers, 2008), 62.

8 “Mackey Pilots Newark Eagles Veteran Catcher Replaces Lundy-Club Meets the Braves Tonight,” Asbury Park Press, August 16, 1940.

9 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, Charles Parks,” Ancestry.com, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?ti=0&indiv=try&db=wwiienlist&h=64115. His draft registration card lists address as 1047 Brown Street, Precinct 2, Ward 2, Charlotte, North Carolina. He is noted as 5-foot-9 ½ and 189 pounds (these numbers vary somewhat with one military record showing him at 5-foot-8 and 188 pounds.)

10 “North Carolina, Death Certificates 1909-1976, Maggie Parks,” Ancestry.com, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=1121&h=1247753&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=ROA102&_phstart=successSource.

11 Jim Overmyer, “Something to Cheer About: The Negro Leagues at the Dawn of Integration,” The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1997 (Jackie Robinson) (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2000), 66.

12 “Day and Irvin Star at ‘Borican Day’ in Newark Doubleheader,” New York Age, September 6, 1941.

13 “Charles Parks Played With Baseball Greats,” Charlotte Observer, September 19, 1987.

14 James J. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994). 604.

15 Verlee Parks’ name also appears as Veblee.

16 “Battle Tested Hero Awards to Forty in 761st Tank Outfit,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 7, 1945.

17 James J. Riley, 604. Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Data Base http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1947&teamID=NE&LGOrd=1

18 North Carolina, Death Certificates, 1909-1976 for George S. Parks.

19 Records to confirm this information are difficult to locate. All names, however, do appear in his obituary. “Charles Parks Played With Baseball Greats,” Charlotte Observer, September 19, 1987.

20 “Redwings To Battle Jacksonville Tonight,” Greensboro Daily News, July 7, 1948.

21 “Greensboro Nine Foe Of Pelicans Tonight,” Asbury Park Press, July 20, 1948.

22 “Greensboro Team At Stadium Today,” Hartford Courant, August 8, 1948.

23 “Blues Open Spring Slate Here Today,” Asheville Times-Citizen, March 27, 1949.

24 “Blues, Red Wings Clash In Opener Here Tonight,” Asheville Times Citizen, April, 5, 1949.

25 “Charles Parks Played With Baseball Greats,” Obituary, Charlotte Observer, September 19, 1987.

26 “Charles Parks Played With Baseball Greats,” Charlotte Observer, September 19, 1987.

Full Name

Charles Ederson Parks

Born

June 19, 1917 at Chester, SC (US)

Died

September 13, 1987 at Salisbury, NC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.