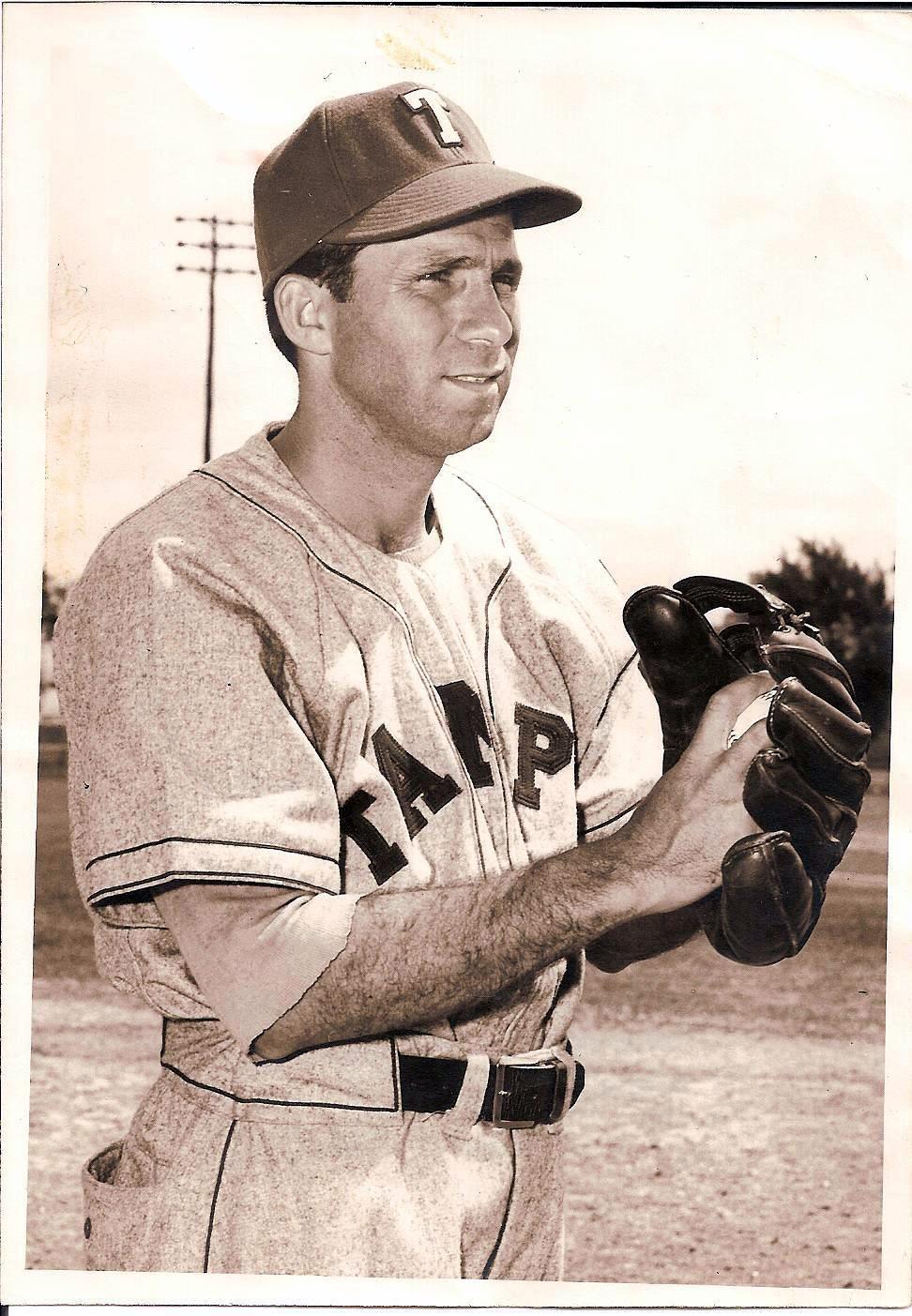

Charlie Cuellar

“I’ve been everywhere, man, I’ve been everywhere”

“I’ve been everywhere, man, I’ve been everywhere”

– Geoff Mack

“Hell, he played in every city in the country.”[1]

– Benny Fernandez, Charlie Cuellar’s teammate with the Tampa Smokers

Fernandez may have been guilty of some exaggeration – but these seem appropriate tributes to Charlie Cuellar, the “Marco Polo of the minor leagues.” The Florida-born right-hander, whose career spanned the years 1935 to 1953, won over 200 games in the minor leagues and pitched a no-hitter in 1947. He made it to the major leagues in 1950 for a few days with the Chicago White Sox, pitching in two games. Yet he had no regrets: “I loved every minute of it. My life was baseball.”[2]

Jesús Patracis Cuellar was born on September 24, 1917, in Ybor City, a historic neighborhood in Tampa founded by cigar manufacturers.[3] He grew up in a baseball-oriented atmosphere. He was schooled only through George Washington Junior High School in Tampa, graduating in 1932.[4] A right-handed pitcher and batter, his baseball schooling came on the sandlots at Tampa Civic Playground and on the West Tampa Post 248 American Legion team. “The Legion coach, Charlie Allen [who earlier had been a coach with the Tampa Smokers], was very good. If I threw the ball high, he would tell me to shorten my stride. Things like that.”[5]

Cuellar described his childhood in a 1994 interview:[6]

“I was born here in Tampa, Ybor City, and this is where I grew up. My parents, John and Regla Cuellar, were from Cuba. During the 1890s, my daddy came over, like so many others, to work in the cigar factories, and when he found a job, my mother came too. I’m not positive but I think my grandparents immigrated to Cuba from Spain, most of them had. Both of my parents went to work in the cigar factories. My daddy was a cigar maker and my mother was what they called a stripper. She stripped the vein from the tobacco leaf. They worked there all their lives but they didn’t make any money, maybe five or six dollars a week.

I went to Ybor City Elementary School and George Washington Junior High. I began playing ball when I was ten years old. I loved to pitch and I did so every chance I could. I had a good curveball and I got better and better. We used to play at the city park in West Tampa and for the American Legion team there. When I played on that Legion team, we missed winning the National American Legion Tournament by one game. We got all the way to the finals and we lost to Gastonia, North Carolina. That was in 1934. After that I graduated from junior high and by the next year I was playing professional baseball.”

Cuellar was signed in 1935 by the Cincinnati Reds, who were conducting spring training in Tampa at the time. Charlie Dressen, the manager of the Reds, took a liking to Charlie and sent him to the Minneapolis Millers, a Cincinnati farm club of the Reds, who were training in Deland, Florida. They in turn sent him to Decatur, Illinois, in the Class D Three-I League.[7] Frank McCormick and Birdie Tebbetts were two future major leaguers who played with Charlie at Decatur in 1935. Cuellar went 3-7 in his first year of organized baseball. “I made $90 a month in Decatur and thought I was rich. My Daddy was working here (Tampa) in a cigar factory and making $6 or $7 a week.”[8] “My parents didn’t mind my leaving home to play ball. My daddy was a great baseball fan.”[9]

Cuellar was only 125 pounds when he was signed but weighed 160 at the end of his first season in organized baseball. During the winter of 1935-36, he went on a special diet in the hopes of getting up to 175 by the start of the 1936 season (he eventually grew to 5’11” and 183 pounds.). [10] [11]

Although hoping to land a spot with Minneapolis in the American Association in 1936,[12] Cuellar was sent to Marshall, Texas in the East Texas League. He went 3-3 in 1936 with Marshall and is listed as “inactive” for 1937. At this point things get a little hazy in Cuellar’s career. It is difficult to follow the exact chronology for 1937 and 1938. Charlie seems to have sat out the 1937 season for reasons not completely clear, although he apparently had a contract with the Marshall team. By one report, he was injured.[13]

Prior to the 1938 season he was sold to Pensacola of the Southeastern League and won two games before he was optioned to Tyler of the East Texas League. There Cuellar submitted a claim to Organized Baseball for free agency.[14] That claim was not upheld but he was made a free agent later in the year.[15] In June 1938, minor league czar Judge W.O. Bramham ruled that he was a “classman,” which meant that he had too much experience to play with Tyler. Bramham counted the 1937 season as a season of play; even though Cuellar had sat out 1937, he apparently did not get his release from Marshall.[16] After Charlie was released by Tyler, he signed with Palestine of the same league.

On July 20, 1938, Cuellar, playing for Palestine, pitched for the South team in the East Texas League all-star game. His pitching was a feature of the game. He was the “complete master” when he pitched the final four innings and got credit for the 5-4 win.[17]

Around the first of August 1938, Cuellar was sold by Palestine back to Tyler, the transaction occurring because “[Tyler] has an excellent chance of getting into the league playoff and believes that Cuellar will help get them into the championship series.”[18] Charlie won two games in the first round of the playoffs versus Marshall.[19] He started the East Texas League championship series playoff opener as fourth-place Tyler beat Henderson 8-4. Cuellar was raked for four hits and three runs in the first two innings before giving the ball to a reliever at the start of the third inning.[20] Tyler ultimately won the playoffs, so the Cuellar acquisition was a good one.

After the 1938 season, Charlie was declared a free agent by Commissioner Landis because he was underage when Decatur signed him and his father had not signed the contract.[21] In 1939, he signed with Reidsville of the Bi-State League and won 17 games. That off-season he played his first winter baseball in Cuba for Almendares, where Dolf Luque was one of his managers. The following spring he was given a tryout with the Brooklyn Dodgers, based on his winter in Cuba.

In 1940, with Leaksville-Draper-Spray of the Class D Bi-State League, he won 17 games. The following year, 1941, he won 16 with that North Carolina club. According to Cuellar, in one stretch during the 1940-1941 seasons, he went 40 games without being relieved.[22]

The 1942 season with Leaksville-Draper-Spray may have been Cuellar’s best year. He won 22 and lost 6, striking out over 200 batters, with an ERA of less than 2.00. He started 28 games and completed 27 of them.[23]

Before the 1943 season, Cuellar’s contract was sold to the Chicago Cubs.[24] The Cubs notified him to report to Tulsa, but the Texas League folded and he was told to report to Macon, Georgia in the South Atlantic League. That circuit also folded, so he wound up with Portsmouth, Virginia in the Class B Piedmont League.[25] After he won four games for Portsmouth, Charlie was sold again to Tyler, Texas.[26] Tyler disbanded, so he returned to Tampa for the rest of the year and worked in the shipyards.

While in Tampa, Cuellar pitched for the shipyard team and the Cuban Club in the Tampa Inter-Social League. [27] This league was made up primarily of Latino players living in Ybor City and West Tampa.[28] Although statistics are not available, it is clear that Charlie was an integral part of the Cuban Club, which won the league playoffs. He pitched and lost the opening game, but came back to pitch the fifth game, scattering six hits. The Cuban Club won the championship trophy.[29]

For the 1944 season, the Cubs assigned him to Nashville of the Southern Association. Cuellar won his first eight games, all complete games, with Nashville.[30] He finished with a 16-7 record but then got hurt.[31] According to Charlie:

“I was unable to pitch the last month of the season on account of an arm injury. My arm would tighten up and cause me a great deal of pain. From then on, every time I pitched I’d have to spend a lot of time warming up. This is what hurt me later on the big leagues. If I hadn’t hurt my arm in Nashville I would have won a lot more games. I tried to have it worked on. I used to go to this doctor in Miami and he would pull on it and stretch it and he could make it feel good. But once I pitched again it would get tight on me.”[32]

From Nashville, Cuellar went to Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League for the 1945 season. He won 13 and lost 17 for a team that lost over 100 games. Charlie decided that he had had enough of Los Angeles and their losing, so he refused to report the following year and was allowed to make a deal for himself.[33] Because he always wanted to play at home, he arranged a deal between Los Angeles and the Tampa Smokers of the Class C Florida International League. On May 22, 1946, The Tampa Morning Tribune announced that Cuellar had been acquired from Los Angeles for an “unannounced sum.”

The righty won 11 games and lost 5 for the Smokers in 1946. He stayed with Tampa for the 1947 and 1948 seasons, going 15-7 and 17-10. Although winning a lot of ball games there, many years later Charlie thought differently about his career choice.

“That was a big mistake of mine, staying here with the Smokers. I should have gone back (to Los Angeles). The Pacific Coast League was a higher classification league and I would have been better off staying there. But baseball was like a chain gang then. Once you signed a contract you were obligated to that team for as long as you played ball and for whatever pay they gave you unless they released you. The players didn’t have the upper hand then like they do now. So when I had the chance to go home and play I took it.”[34]

On July 23, 1947, the 29-year-old Cuellar twirled one of his finest games. He pitched his first no-hitter in Organized Baseball against the league-leading Havana Cubans before a crowd of 3,102 in Tampa. Only three Cubans reached base, one on a walk and two on errors, as he struck out eight. The only hard-hit balls were two line drives directly at fielders.[35] After the game, Charlie was quoted: “I knew all along that I had a chance for a no-hitter as “Doc” Blanco, club trainer, told me in the fifth inning to bear down as I had allowed no hits. As the game continued toward the late innings I really bore down with everything I had. I had my control for the first time this year and I really felt good out there on the mound before those fine Tampa fans who cheered me on as I finally succeeded in getting a no-hit game. I’ve pitched quite a few one-hitters but never a solid blank game.”[36] After the game the crowd went wild with enthusiasm and littered the field with cushions and paper programs.[37]

There was some controversy with the game, as told by Tampa Smoker teammate Bitsy Mott almost 50 years later:

‘Late in the 1947 season Havana came into Tampa and Charlie Cuellar, who was pitching for us, threw a no-hitter against them and the place went wild. Those Tampa fans just loved it. But I’ll tell you, there is a little controversy surrounding that no-hitter. Now I’m not saying this to down Charlie but he had friends on that club. Charlie was a local-born Cuban. He used to talk Spanish together with them and all that. He’d even played some ball with a few of their players. Well, the last batter up, I can’t recall his name but a real good friend of Charlie’s, just waved at the pitches for the final out. It was something that looked bad for both clubs really. I’m sure that it did for Charlie. It wasn’t planned out in advance or anything like that but the guy did intentionally make the out. Now of course, eight and two-thirds worth of batters went down without a hit so it wasn’t all bad. I’m just telling you what happened.”[38]

Because of overwhelming fan reaction, Tampa club president Tom Spicola scheduled a day in Cuellar’s honor to be held August 7.[39] However, due to rain “Charlie Cuellar Day” was moved to the following day when he would hurl the second game of a doubleheader. Again it rained during the day and only one game was played that evening. In that game, before 2,024 fans, Charlie beat the Miami Beach Flamingos, 7-3, striking out 12. Prior to the game, Cuellar was called to home plate and given a long list of gifts and donations including two pair of baseball shoes, a chenille bed spread, a Bulova wrist watch, a shirt, luggage, a six-tube radio, an electric shaver, a shirt and tie set, a $200 merchandise certificate, $100 cash and a trophy from the Cuban Club.[40]

Cuellar began 1949 with Tampa and early in the season in a surprise deal he was sold to Lakeland, Florida of the same league. According to sportswriter Wilbur Kinley, the deal was made because of contract problems – Charlie was asking for too much money from Tampa.[41]

In 1949 while pitching for Lakeland, Cuellar recorded his 200th minor league victory, a 4-3 win over the St. Petersburg Saints. He had tried three times after his 199th triumph, pitching a two-hitter and two five-hitters but losing each time by one run. At the time of his 200th victory, Charlie had 112 defeats. (See the afterword at the end of this story.)

In 1950, Cuellar was named Lakeland’s playing manager, but he resigned as skipper on June 17 after the Pilots had dropped a 4-2 decision to Tampa. Lakeland was 29-45 under Cuellar.[42]

On June 25, 1950, the Chicago White Sox announced that “Charley Cuellar, 31-year-old Cuban-born right-handed pitcher, would follow the team tonight to Detroit for a trial workout.”[43] (This item appeared in The New York Times on June 26, 1950. At least the Times got it correct that Charlie was right-handed; otherwise, it misspelled his name, misidentified his birthplace, and got his age wrong.) The misidentification continued in The Washington Post in an item dated July 1, 1950, which read: “The Chicago White Sox today signed Robert Cuellar, 31-year-old Cuban right handed pitcher of Tampa Fla. and released Pitcher Jack Bruner to the St. Louis Browns for the $10,000 waiver price. Cuellar formerly managed and pitched for the Lakeland, Fla. Club of the Florida International League. He scored seven victories for Lakeland, five of them shutouts.”[44]

Although the circumstances of Cuellar’s call-up to the Sox cannot be accurately ascertained, a 1989 article in the Tampa Tribune stated that Lakeland’s Johnny Rizzo, a former major leaguer, pushed to get him to the majors. The Chicago Tribune noted that Charlie was a “St. Petersburg neighbor” of Chicago White Sox General Manager Frank Lane.

Charlie made his debut with the White Sox on July 2, 1950, wearing uniform # 28.[45] He pitched the 10th inning in an 11-inning White Sox loss to the St. Louis Browns at Chicago. He retired the first two batters, then the Browns loaded the bases, but Sherm Lollar flied out to end the inning. He struck out one batter, allowed two hits, and walked one.

Cuellar’s second and final major league appearance was in the second game of a July 4 doubleheader at Comiskey Park against the Detroit Tigers before 35,998 fans, after the Sox had taken the opener 4-1. Edward Burns of the Chicago Tribune described the circumstances of Cuellar’s appearance in some detail. This description of events has not been corroborated or discounted by any other source:[46]

“The second game, which the Tigers won, 10 to 9, was a melange of bad and good pitching on both sides, [White Sox] Manager Johnny Corriden’s first severe attack of cerebral fog, and a fiasco generally in which the losers made 14 hits to the winner’s eight…”

“Corriden’s aforesaid cerebral breakdown consisted of calling in one Charley Cuellar to pitch after the Sox had shaved the Tiger’s initial 4 to 0 lead to 4 to 3. Cuellar, a St. Petersburg, Fla., neighbor of General Manager Frank Lane, was a 31 year old free agent fugitive from the Class B Florida International League, signed last week for batting practice duty.

Lane expressed as much surprise as anyone when Corriden summoned Charley with the Sox moving up and only one run behind. The six runs the Tigers made in the fifth all were charged to the earnest and unfortunate rookie, who really was tossed in quite a spot, considering the Tigers’ position in the pennant race.”

Cuellar was summoned by Corriden to pitch the top of the fifth inning. Bob Cain had started the game, was knocked out in the first inning and replaced by Howie Judson, who pitched through the fourth before he was removed for a pinch hitter.

In his stint on the mound, Cuellar retired one batter, walked two and allowed four hits. He never appeared in the major leagues again. During his two appearances, Charlie pitched 1 1/3 innings, faced 13 batters, allowed six hits and three walks, and struck out one. He allowed five earned runs for an ERA of 33.75. He did not bat in the major leagues.

The next day July 5, 1950, the White Sox released Cuellar and acquired pitcher Lou Kretlow from the St. Louis Browns.[47]

In an interview 50 years later, Charlie said:

“When I was managing at Lakeland, 1950, I was sold to the Chicago White Sox. I could have gone to the Washington Senators or the White Sox but I picked Chicago and made a mistake. Back then most of the Cuban players that went to the big leagues went to the Senators and did real good. I should have gone there too but I didn’t. Do you know what it is in this business for a guy like me to win two hundred games before ever getting to the big leagues? That was unbelievable! Believe me, I still don’t know what took them so long because I was a winner wherever I went.

There was a scout down here – I can’t remember his name – that kind of liked me and he thought that I could pitch in the big leagues. I would have too if they hadn’t put me as a relief pitcher. I had always been a starter and they put me in there as a reliever and I just wasn’t a relief pitcher. I could never pitch in relief. Plus, remember when I was in Nashville I hurt my arm and I couldn’t pitch every other day or always be getting up to throw in the bullpen. If I could pitch every third or fourth day I would give you a good game. But once I warmed up I had to go ahead and pitch. I couldn’t sit back down and wait just because the pitcher that was in there had settled down. My arm couldn’t take the ups and downs of the bullpen. It was hard for me to go through that and frustrating too. I couldn’t do it. I appeared in two games for Chicago and got shelled. I guess it was my tough luck not to make it in the big leagues, because everywhere else I went I was a winner.”[48]

However, Cuellar was not out of a job long. On July 10, 1950, the Memphis Chicks of the Southern Association signed him.[49] He went to Memphis and immediately won seven games as a starter. However, he got into arguments with manager Luke Appling, who wanted Charlie to pitch batting practice. Cuellar refused, so he returned to St. Petersburg of the Florida International League in 1951. He also played briefly with Augusta of the South Atlantic League in 1951. His combined record with the three teams in 1951 was 10-8.

In 1952 he was with St. Petersburg and Havana, both of the Florida International League, and produced a 3-4 combined record, his first losing record since he went 3-7 with Decatur in his first year in organized baseball.

In April of 1953, the Keokuk (Iowa) Kernels of the Class B Three-I League – the same circuit where he started his career – announced the signing of Cuellar. The Keokuk Daily Gate City called him “a veteran righthander who was with the Chicago White Sox during a portion of the 1950 baseball wars.” Undoubtedly the reason Charlie was signed by Keokuk was Kernels manager Rudy Laskowski, who had played and managed contemporaneously for a number of years with Charlie in the Florida International League. In addition to Cuellar, Laskowski brought many other former FIL players to Keokuk. Upon the signing of Cuellar, Laskowski was quoted, “Charlie’s a fine pitcher and I feel he’ll really be a great help to the squad. He’s a veteran in every respect and should really find the Three-I League to his liking.” Charlie was also described by the Gate City as a “fancy dresser and good looking.”

Cuellar was the opening day hurler for the Kernels and started a second game on May 9. He did not make another appearance until June 7, so it would appear that he may have been injured during that time. He apparently went back to Florida during this period, as the June 6 Daily Gate City reported:

“Hurler Charlie Cuellar came straight to Keokuk instead of meeting the team in Terre Haute. Charlie intended to be on hand for the final (Terre Haute) Phillie game but was picked up for speeding in a small town in Mississippi and spent 6 hours in the clink. Southern hospitality??”

The highlight of this stint occurred on July 10, 1953, when he faced the Burlington Flints and pitcher Johnny Vander Meer at Keokuk’s Joyce Park – the same Vander Meer of double no-hit fame, who had become the playing manager for the Flints. Charlie was up to the task, as he shut Burlington out, 9-0. Although these were a couple of over-the-hill pitchers, it still must have been a lot of fun to see former major-leaguers go at it on the mound. Only the 779 fans in attendance could claim they saw this matchup.

For the 1953 season with Keokuk, Cuellar went 5-4 with a 4.14 ERA, making 12 starts and pitching 76 innings, averaging over six innings a start with four complete games. On August 3, 1953, he announced that he was leaving the Keokuk team because “he just could not stand the pain anymore and had to leave.” Cuellar was suffering from an arm ailment and from stomach trouble.[50] Keokuk was his last stop as a player in Organized Baseball.

Cuellar was appointed manager of the Tallahassee Rebels of the Florida International League on July 21, 1954, replacing Gene Harvey, who had been acting as interim manager since the resignation of Duke Doolittle.[51] He was only there two days when the league folded.

Many newspaper articles referred to Cuellar as a “Cuban” although he was born in the United States. A July 20, 1944 Sporting News item noted that he wanted the world to know “he is a Spaniard and not a Cuban.” According to Florida historian Wes Singletary, this was a big deal in the Tampa area. Many of the players, including Al Lopez, had parents that had lived in Cuba for years prior to coming to Ybor City (Tampa) but were from North Spain. The Asturiano pride found being called a Cuban unacceptable and they didn’t let it go.

Was there a spitball issue with Cuellar? From The Sporting News of August 24, 1949:

“A lot of fans think I throw a spitball because opposing managers are always complaining to the umpire about my delivery. I have never thrown a spitter and don’t know how. Just before I pitch I blow on my hand to moisten it. My hands are very dry because I perspire very little and I can’t control the ball. The umpires know I’m not throwing illegal deliveries so it doesn’t worry me when opposing managers squawk.”

After his playing career, Cuellar started painting houses. He learned to do woodworking on his own and word began to spread about the quality jobs he did. He started building full time, became a master craftsman, and began remodeling penthouses, beach condominiums and offices and houses. His work was featured in Tampa Bay Southern Homes and Tampa Bay Homes magazines.

Cuellar had one daughter, Cheryl Lodato, who currently lives in Tampa, with his first wife Isabelle Gullo, whom he married in 1940. Charlie built Cheryl’s home in 1988 with all the woodwork that he so loved. He was very proud of his accomplishments and master craftsmanship. He was married to his second wife, Dahlia, for over 30 years. They had met at a tea dance at the Centro Español Club in Tampa. Charlie said that Dahlia was always a good fan and enjoyed his playing. Dahlia worked at Tampa Electric for 38 years before retiring in 1990.

Charlie died in Tampa of natural causes on October 11, 1994. He is buried in Centro Asturiano Cemetary in Tampa.[52]

Afterword: In researching this biography, I found a significant discrepancy in the number of minor league games Charlie Cuellar claims he won vs. the number of games in the record books of Organized Baseball. Cuellar claimed he won 253 games against 130 losses, with his 200th win coming in 1949 as described above. Contemporary newspapers also cited the 1949 game as his 200th minor league win. Sources including www.baseball-reference.com give him a 209-139 record. Even allowing for a few “less-than” wins undocumented in the record books of the time does not allow Cuellar’s win total to rise to 250. I spent considerable time attempting to resolve this discrepancy but could not come to any definitive result.

I ultimately came to the conclusion that Cuellar overstated his number of wins, probably including those in winter ball or other non-organized ball, such as the 1943 Tampa Inter-Social League – or possibly even playing under an assumed name. For example, there is no record for him in the 1937 season and he had free agent issues with the commissioner the following year. We don’t know what was he doing, where was he playing (if at all) or if possibly he was playing under another name, which was not uncommon at the time. As also described in the narrative, The Sporting News along with the local Florida papers noted that Cuellar recorded his 200th win in 1949. Again, I could not verify this as win #200, so I presume that the overstatement was Charlie’s intentional or unintentional doing.

Reading the 1989 Tampa Tribune interview and the Wes Singletary interview, I saw that Charlie was quite a guy. It would have been a pleasure to meet him.

December 15, 2011

[1] The Tampa Tribune, January 19, 1994

[2] The Tampa Tribune, June 14, 1989

[3] Baseball-Almanac.com

[4] Sports.tbo.com/sports/boggs/hillsboroughpros.htm

[5] The Tampa Tribune, June 14, 1989

[6] Singletary, Wes. Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2006: 111

[7] Ibid.: 112

[8] The Tampa Tribune, June 14, 1989

[9] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 112.

[10] The Sporting News, December 26, 1935: 4

[11] Baseball-Almanac.com

[12] The Sporting News, December 26, 1935: 4

[13] Undated article from unidentified newspaper in Cuellar family scrapbook, page 36.

[14] The Sporting News, June 1, 1944: 25.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Article dated June 19, 1938 from an unidentified newspaper. Page 25 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[17] The Corpus Christi Times, June 20, 1938.

[18] Undated article from unidentified newspaper contained in Cuellar family scrapbook.

[19] Undated, unidentified article, page 35 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[20] Port Arthur News, September 8, 1938.

[21] Undated Fred Russell column, page 88 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[22] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 114. This claim has not been documented, however, although the number has not been verified, there is some veracity to Cuellar’s claim in accounts from various sources.

[23] Nashville Banner newspaper article, June 18, 1944, in Cuellar family scrapbook.

[24] Undated unidentified newspaper article, page 65 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[25] Undated Fred Russell column page 88 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[26] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 114.

[27] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 114.

[28] Singletary, Wes. “The Inter-Social League: 1943 Season.” Sunland Tribune, Vol. XVIII, 1992

[29] Singletary, Wes. Updated article “The Inter-Social League: 1943 Season.” Provided to Steve Smith by Wes Singletary.

[30] Undated, unidentified newspaper article, page 82 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[31] The Sporting News, August 24, 1949: 46.

[32] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 115

[33] The Sporting News, August 24, 1949: 46.

[34] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 116.

[35] The Sporting News, August 2, 1947: 34

[36] Tampa Morning Tribune, July 24, 1947

[37] Ibid.

[38] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 102. A few newspaper accounts do give some credence to Mott’s story.

[39] The Sporting News, August 2, 1947: 34

[40] The trophy given by the Cuban Club remains in the possession of Charlie’s daughter, Cheryl Lodato.

[41] Undated Wilbur Kinley column, page 155 of Cuellar family scrapbook.

[42] The Sporting News, June 28, 1950: 38.

[43] The New York Times, June 26, 1950

[44] The Washington Post, July 2, 1950

[45] Baseball-Almanac.com

[46] The Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1950

[47] Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1950. The Sporting News, July 12, 1950: 58.

[48] Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: 117.

[49] The New York Times, July 11, 1950

[50] Keokuk Daily Gate City and Constitution Democrat, August 3, 1953.

[51] The Sporting News, July 28, 1954: 38.

[52] Baseball-Almanac.com

Full Name

Jesus Patracis Cuellar

Born

September 24, 1917 at Ybor City, FL (USA)

Died

October 11, 1994 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.