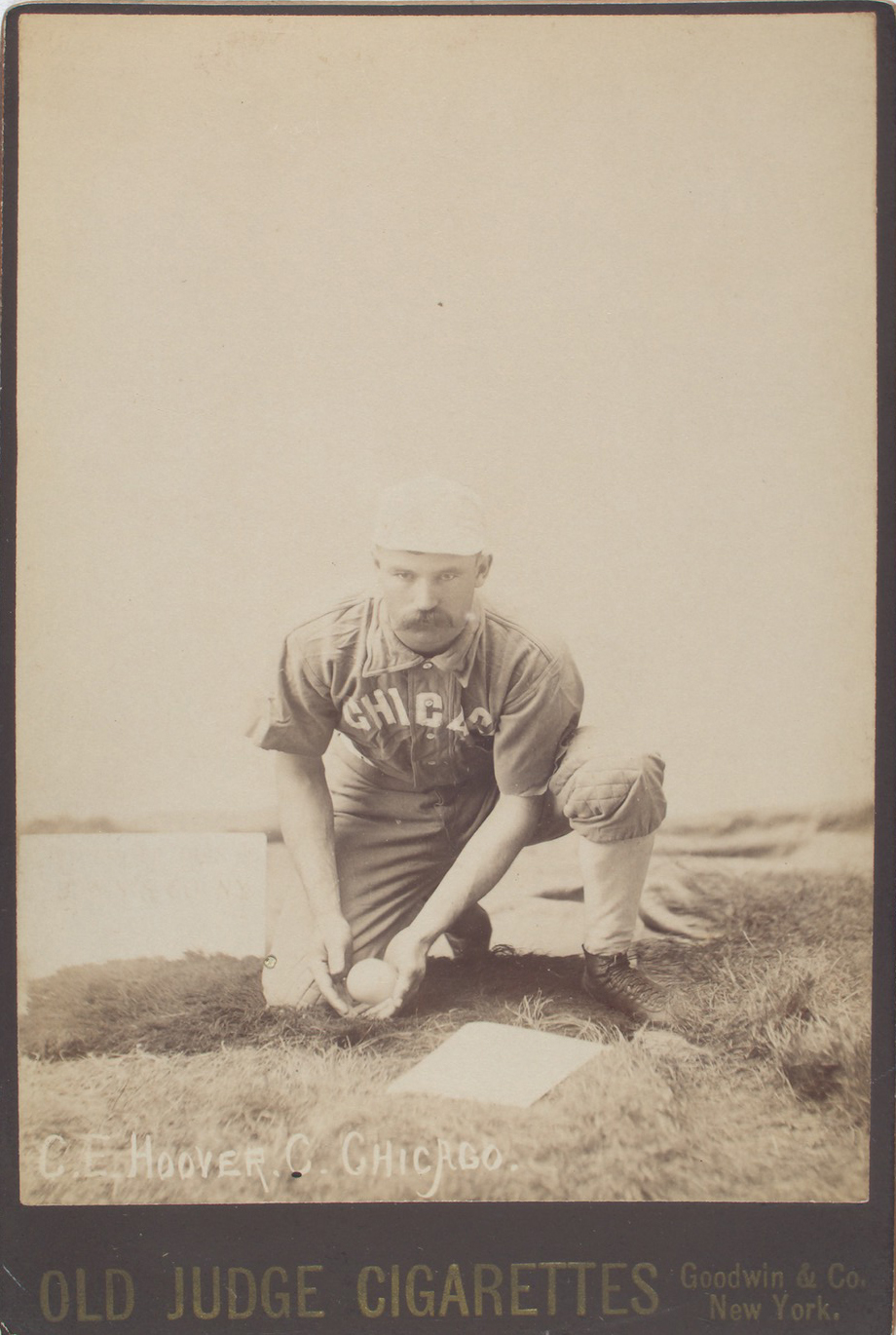

Charlie Hoover

Catcher Charlie Hoover debuted with the Kansas City Cowboys in the American Association on October 9, 1888, one month after he turned 23. “Hoover made his debut behind [Henry] Porter and did well in the field,” wrote the Kansas City Times, despite two errors against one assist.1 Described as 170 pounds and 5 feet 9 inches in the San Francisco Call in 1891, Hoover was a right-handed throwing, left-handed hitting catcher.2 According to his prison record, he had black hair, brown eyes and a dark complexion.3 His major league career ended just one season after his debut, not because of a lack of talent, but a lack of discipline and a fondness for the bottle. He played his last season of professional baseball in 1895. Four years later, Hoover was in prison. Pardoned in 1902, he wandered south to Louisiana where he played for an independent club organized by former Southern League player Sham Meyers in Shreveport. The fate of Charles Hoover had been unknown until 2020, and evidence suggests he died in Shreveport, Louisiana, on February 27, 1905, at the age of 39.

Catcher Charlie Hoover debuted with the Kansas City Cowboys in the American Association on October 9, 1888, one month after he turned 23. “Hoover made his debut behind [Henry] Porter and did well in the field,” wrote the Kansas City Times, despite two errors against one assist.1 Described as 170 pounds and 5 feet 9 inches in the San Francisco Call in 1891, Hoover was a right-handed throwing, left-handed hitting catcher.2 According to his prison record, he had black hair, brown eyes and a dark complexion.3 His major league career ended just one season after his debut, not because of a lack of talent, but a lack of discipline and a fondness for the bottle. He played his last season of professional baseball in 1895. Four years later, Hoover was in prison. Pardoned in 1902, he wandered south to Louisiana where he played for an independent club organized by former Southern League player Sham Meyers in Shreveport. The fate of Charles Hoover had been unknown until 2020, and evidence suggests he died in Shreveport, Louisiana, on February 27, 1905, at the age of 39.

Charles E. Hoover was born in Mound City, Illinois, on September 9, 1865, the second child of Daniel L. Hoover (1836-1911) and Eliza Forsythe Hoover (1843-1896). Daniel was a brick mason and Civil War veteran, while Eliza raised five children. Daniel had enlisted in the army in April 1861 right as the war started and was discharged just three months later when an explosion cost him his left leg.4 After Charlie’s arrival, the Hoover family moved from Illinois to Missouri, settling first in La Plata, and then in Hannibal, the hometown to which Charlie returned over the years. Daniel spent his final years at the Quincy Soldiers Home where he died in August 1911.5

Hoover first appeared in a box score playing first base for the independent Hannibal club in a game on May 23, 1885, against the St. Joseph (MO) Reds.6 Hannibal won, 15-5. Two days later he was at second base in a loss to St. Joseph, and filled various position, including catching, through the summer,

In 1886, Hoover played for St. Joseph in April during the preseason, but on May 6, he caught Perry Werden playing for Lincoln, (NE) against St. Joseph on Opening Day of the Western League season. As the season progressed, Hoover was paired with pitcher Frank Hafner as battery mate.7 Hafner was another player from Hannibal, a few years younger than Hoover. They would be teammates again in Topeka in 1887, and both were signed by Chicago for the 1888 season.8 Hoover remained with Lincoln for the entire 1886 season. Stats published at the end of the season by the Kansas City Times put his batting average at .280, tied for 20th in the league.9

Coming off his strong first professional season, Hoover signed with Topeka, (KA) of the Western League for the 1887 season. “Mr. C. E. Hoover, right fielder and catcher, is a powerful [athlete], and fills both positions admirably. Hoover is also a terror to the pitchers.”10 He was injured in late April, then had a bout of malaria, and returned from both in mid-May. He was hurt again in late May after just eight games with the club. Topeka released Hoover in June and he quickly signed with Lincoln again. There he joined another young player from Hannibal, Jake Beckley, who was in his first season in an organized minor league. Lincoln had a strong club, with sixteen players who would eventually have a major league pedigree. On September 15, they were in second place with a record of 61-29, behind only Topeka at 69-32.11 Hoover was batting well over .300, yet days later it was reported that he would be released before the club left on a road trip. “Whisky and dissatisfaction will disqualify any man from playing ball.”12 Despite this proclamation in the paper, Hoover continued playing with the club for a few more days until the Lincoln club folded on September 27, having lost money all season.13 He finished the season with Kansas City. For the year, Hoover hit .342 in 67 games, with 10 doubles, 9 triples and 2 home runs. His success led to a contract with Cap Anson’s Chicago White Stockings for the 1888 season. Charlie Hoover was headed to the majors… but he hit a detour on the way.

At about 2 A.M. on the morning of December 7, 1887, Charles Hoover was arrested in Lincoln after an altercation with a hack driver. According to the report in the Lincoln Evening Call the next day, the trouble started over some prostitutes as they were preparing to head to “a party or ball of questionable pretensions.” A shot was fired, and Hoover was arrested and charged with shooting with intent to kill.14 He was held in jail for a few weeks, and then released after paying a modest fine (about $50) because the major charge of intent to kill could not be proven.15

The following spring, while training with the White Stockings, Hoover broke his finger in a game in New Orleans. While Chicago traveled on to St. Louis to play the Browns, Hoover went back to Hannibal to recover, returning to the club at the start of May.16 Chicago had catchers Tom Daly and Silver Flint returning from the 1887 team, so it is not clear if the injury cost Hoover a chance at playing with the White Stockings, or if he was already slotted as a reserve from the start (or perhaps Anson figured out that Hoover was trouble). In any case, he never played for the White Stockings. Instead, on May 16 he was released to the Chicago Maroons of the minor league Western Association.17

The Maroons were also owned by White Stockings’ owner Al Spalding. Hoover and pitcher Charlie Sprague (who appeared in one game with Chicago in 1887) were both transferred from the Whites Stockings to the Maroons at the end of spring training. Neither made it back to the major league club. Hoover played with the Maroons the remainder of the season, appearing in 60 games (plus one game with Davenport, on August 30, when that club needed a catcher and the Maroons were passing through town). He hit around .250 with less power than he shown the previous season (only one home run, along with six doubles and two triples).18

As the Western Association season came to a close, the Maroons sold Hoover to the Kansas City Cowboys in the American Association.19 He made his major league debut with the Cowboys on October 9. In three games he had 3 singles in 10 at bats. Kansas City reserved Hoover for 1889 at the end of the season. The Kansas City Times wrote that “Hoover is a hard hitter, a clever base stealer, a first-class thrower to bases, and when not excited, an A No. 1 back stop.” The article also noted that he “has but one fault, that of uncontrollable temper.”20

Hoover had a very rocky season with Kansas City in 1889. After an early season injury caused him to miss a few games, he started catching regularly for the club in the second half of May. (Prior to that he played some third base and outfield when he wasn’t catching.) In late May, Kansas City newspapers reported friction between Hoover and pitcher Park Swartzel. “Watkins [Kansas City manager Bill Watkins] makes a great mistake every time he puts Hoover in to catch Swartzel. The men will not work well together, and there is a constant quarrel between them. The crowd at St. Louis yesterday grew so disgusted at Hoover’s kicks against his pitcher that it called for his removal from the field.”21 Hoover caught the next two games, but in June he played in only three games. The Kansas City Star reported on June 7 that “Watkins seems to have shelved John] McCarty and Hoover.”22 At the end of June, Hoover met with club President John Speas and manager Watkins “and used very insulting language to them on account of fines imposed on him for bad conduct during the recent trip. The result will probably be Hoover’s release. He is a magnificent catcher when in condition, but his worst enemy is his ungovernable temper.”23

Hoover patched it up with management a few days later, catching McCarty’s start and the next two days as well. On July 3, Hoover was hitting .313, good for twelfth in the American Association.24 The next day he suffered a compound fracture of the third finger of his right hand, but missed only two weeks, returning on July 18, and subsequently played in 33 straight games as Kansas City attempted to have him set a record for consecutive games caught. This attempt failed in Game 34 when he re-injured his finger. This was probably for the best for Kansas City, as the club was 12-21 during the streak, and there were continued reports of friction between Swartzel and Hoover. Hoover missed another thirteen games, returning on September 18.

Ten days after his return, his season was finished for good, this time because of his temper. On September 28, he came drunk to the game against the Philadelphia Athletics scheduled to catch Swartzel. “It is a well-known fact that there is no love lost between Swartzel and the cranky catcher, and when Swartzel failed to put the ball just where Hoover wanted it he let it go by. Some of the boys on the bleachers made a few remarks and the catcher pulled off his gloves, threw down his chest protector and climbed over it to the seats.”25 Hoover finished the inning at third base, then was removed from the game and suspended for the remainder of the season.26 The Kansas City Times subsequently reported that Hoover returned to Hannibal and suggested that “if he is sensible he will spend the winter meditating on what an ass he has been this season.”27 In 71 games with Kansas City in 1889, Hoover hit .248 with only eight extra base hits.

Despite all the trouble, Hoover was still retained by Kansas City for the 1890 season. However, instead of playing in the American Association, Kansas City jumped back to the Western Association in November 1889, ending Hoover’s major league career.28 He tried to organize a club in Lincoln for 1890, but “he failed… not due to the lack of interest in base ball in this city. It was due to the fact that Lincoln people know Charlie Hoover.”29 He remained with Kansas City, catching Frank Pears and Elmer Smith, but notably not Swartzel or Jim Conway, teammates from the previous season. While no trouble was reported in the Kansas City papers through the first two months, he was suspended indefinitely on June 4. “Hoover’s capers have been a source of much trouble to the club ever since he has been a member of it, but not until this season has his dissipation had any apparent effect on his playing. This season he has not been catching up to his past form.”30 The move came just a couple of days after Kansas City replaced manager Charlie Hackett with Jim Manning.31 Manning had played with Hoover the previous season and likely was less inclined to tolerate his behavior than Hackett.

Upon being suspended, Hoover returned to Lincoln, where he resumed a complicated relationship with a “bewitching” blonde who ran a well-known brothel at Sixth and M streets — and who coincidentally shared his last name: Hattie Hoover.32 In early July, Charlie was arrested for assaulting one of the girls at Hattie’s brothel, Allie Cline; he pled guilty and paid a fine.33 Shortly after that, he was reported to be managing a club of colored players in Hannibal.34 In August, the Des Moines club in the Western Association was transferred to Lincoln, and on August 14, Hoover was formally released by Kansas City so he could sign with Lincoln.35 He appeared in 49 games and hit .206. His fielding percentage was the lowest of the league’s catchers.36

On October 6, the Lincoln Journal Star reported that Hoover was returning to Hannibal, where he was to be married on Christmas evening.37 Less than two weeks later, on October 15, 1890, he was again arrested for assaulting Allie Cline. This time he pled guilty under the name “Ed Smith” and again was released with a fine. On December 12, 1890, he was arrested on charges of trying to kill Hattie Hoover and Joe Scroggins, a card shark who allegedly stole Hattie’s affections.38 The charges were dropped under the conditions that he leave town, which he did, but by late December he was back in Lincoln and reconciled with Hattie. He managed to stay out of trouble until February 1891, when he was signed by Sacramento of the California League for the coming season. He celebrated by going out and getting drunk and again wound up in jail after once more threatening Hattie and her girls. Hoover was released the following day, paid his fine, and caught a train for California. “The community is unmeasurably benefited by the thug’s departure. There is weeping and wailing at Sixth and M.”39

Six months later, Hattie Hoover also left Lincoln. “Hattie Hoover and her two girls left the city on the morning flyer. There will be little regret at their departure.”40 While it is reasonable to assume the girls were children, it is unknown if they were the daughters of Charlie Hoover. It is also not known where Hattie and her girls went after they left town.

The change of scenery didn’t change Hoover or arrest the decline of his chaotic career. He lasted just a few months in California before Sacramento released him on May 13 amidst reports that he had a shoulder problem.41 He returned to Lincoln, where he was arrested for “fast driving” (one assumes a horse and wagon), and then skipped town for Hannibal.42 He was subsequently arrested in Quincy for trying to ride a horse into a saloon while drunk.43 In 1892 and without a baseball gig, Hoover advertised for a position in The Sporting News, claiming he was a reformed person and good as new after hand surgery.44 Omaha made an offer that spring, but Hoover wanted more money than they offered. Instead, he played in the Montana State League, first for Philipsburg, and then Bozeman. Hoover remained in Butte, Montana, until February 1893 when “the town became so hot for him that he shook the dust off his feet and returned to his Hannibal, Mo, home.”45 He had his last chance to play in the majors that spring when Charlie Comiskey brought him to Cincinnati as a possible backup for Henry “Farmer” Vaughn. A couple of weeks into the season, before Hoover appeared in a game, he got into a fight while drunk at a pool hall in Cincinnati and was released.46 There were reports that he signed with Macon in the Southern League, and then later St. Joseph in the Western Association, but there are no records he played for either club, nor any other that season. In 1894, he played for three clubs in the Southern Association (Macon, Charleston and Savannah). In 1895, at the age of 29, he played for the Jacksonville (IL) Jax in the Western Association. He lost his temper at the crowd during a game on July 26 and was released shortly thereafter.47 In 1896, he managed a club in Bushnell, Illinois; it was his last year in professional baseball.

Every time there was a Charlie Hoover sighting, there was a comment about his temper or his drinking. “In condition and at himself, Hoover is one of the best catchers in the country. He is also a timely hitter and a heady ball player, and it has been his bad habits alone that kept him out of the fastest company in the business.”48 This was the perfect encapsulation of his career.

In October 1898, Hoover finally met the fate he had avoided for many years — actual prison time. He and a partner were arrested in Hannibal for forging a check. He was sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary beginning in January 1899. Hoover’s inmate record described the second, third and fourth fingers on the left hand as crooked, the price of years of catching without a glove. Missouri Governor Alexander Dockery pardoned him in May 1902. A month later a Nashville paper said he had signed with Memphis of the Southern League, and that he was “in uniform” in Shreveport, Louisiana. He never played for Memphis.49 As of 2020, no information has been found to explain what happened to Hoover next.

In the initial review of this biography, a reference was found in the Shreveport Times from 1903 reporting that Charles Hoover, former catcher for Cincinnati, was playing with an independent club there organized by a former Southern League player, Sham Meyers.50 A year later a notice in the Shreveport Journal reported that a partnership in Shreveport between S. Bellams and C. E. Hoover, brick contractors, was dissolved, with all accounts to be settled by S. Bellams.51 On March 5, 1905, a Shreveport paper included C. E. Hoover in a list of recent deaths in the city.52 According to his gravestone in Greenwood Cemetery, C. E. Hoover died on February 27, 1905. While not conclusive, the final resting place of Charlie E. Hoover, alcoholic and baseball player, appears to have been found. Charles Hoover was praised as a catcher and condemned as a person. His career started brightly, but his drinking brought it to a premature end and ultimately landed him in jail. When he died, not even his full name was put on his gravestone.

Acknowledgments

This bio was reviewed by Paul Proia (who conducted additional research, including the 1903 reference to Hoover playing in Shreveport) and Norman Macht. It was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

US Census data was accessed through Geneology.com and Ancestry.com, and other family information was found at FindaGrave.com and Ancestry.com. Stats and records were collected from Baseball-Reference unless otherwise noted. Articles cited in this biography were typically accessed through Newspapers.com and/or Geneology.com. An article posted on The Infinite Baseball Card Set blog (http://infinitecardset.blogspot.com/2013/03/146-charlie-hoover-talented-but-troubled.html) in 2013 by Thom Kartik provided guidance for the research for this biography.

Photo: New York Public Library, Spalding Collection.

Notes

1 “Cincinnati 13 — Kansas City 6,” Kansas City Times, October 10, 1888: 3.

2 San Francisco Call, March 23, 1891: 8.

3 From the Missouri State Penitentiary Database.

4 The record for Daniel Hoover in the Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938 indicates he enlisted in Cairo, Illinois in April of 1861 and was discharged in July of 1861, with the cause of discharge listed as “Explosion” and the disability identified as “Loss L. leg.” It lists two daughters, Mrs. Nettie Heffner and Miss Edna Hoover, as his nearest relatives, in Hannibal, Missouri.

5 Monroe (Missouri) City Democrat, August 10, 1911: 4.

6 “Honies From Hannibal”, St. Joseph Gazette-Herald, May 24, 1885: 4.

7 “A Good Game,” Nebraska State Journal, May 22, 1886: 8.

8 “New Chicago Players Signed,” Sedalis (Missouri) Weekly Bazoo, October 25, 1887: 1. While Hafner signed with Chicago, in March 1888 he reported to the Kansas City Cowboys in the American Association for spring training.

9 “Western League Records,” Kansas City Times, October 17, 1886: 3.

10 “Grand Opening. Of the Western League Ball Season in Topeka To-morrow,” Topeka Daily Press, April 20, 1887: 4.

11 “Western League Standing,” The Nebraska State Journal, September 15, 1887: 1.

12 “Base Ball. The Lincoln Club Fairly Annihilated at Topeka,” Lincoln Evening Call, September 21, 1887: 4. Lincoln had lost two games the day before by scores of 11-7 and 22-0.

13 “The Act of Dissolution,” Lincoln Evening Call, September 27, 1887: 1.

14 “Shooting with Intent to Kill,” Lincoln Evening Call, December 7, 1887: 1.

15 “The Hoover Case,” Nebraska State Journal, December 23, 1887: 8.

16 “Chicago Boys in St. Louis,” Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1888: 6, and “Incidents of the Game,” Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1888: 6.

17 “Base-Ball Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1888: 3.

18 Statistics from the 1888 Western Association season on Baseball-Reference (and other sources) are not always complete and sometimes contradictory. The Sporting Life published the “Official Records for the Season of Clubs and Players” in the December 14, 1888 issue, which reported that Hoover played in 58 games, with 202 at-bats and 48 hits, for a .237 average.

19 “The Cowboy Club,” Kansas City Times, October 6, 1888: 3. The Maroons ended their season in Kansas City against the Kansas City Blues of the Western Association on October 5, 1888. The Blues and Cowboys had previously agreed to merge for the 1889 season.

20 “A Fine Battery,” Kansas City Times, February 24, 1889: 3.

21 “Base Ball Notes,” Kansas City Star, May 27, 1889: 2.

22 “Base Ball Notes,” Kansas City Star, June 7, 1889: 2 At this point neither had played since the game on May 30, 1889, which was an 8-2 loss to Baltimore. McCarty was 7-4 after that loss. McCarty pitched on game in June, with Hoover catching. Hoovers caught John Sowders in his other two games in June, the latter’s first two starts after being purchased from St. Paul.

23 “Hoover’s Days Are Numbered,” Kansas City Times, June 28, 1889: 2.

24 “Holliday Heads the List,” Kansas City Times, July 3, 1889: 5.

25 “Hoover Carried A Jag,” Kansas City Times, September 29, 1889: 6. The article subsequently described how the fan Hoover was seeking “was just at this time the quietest man in the grounds.”

26 The rules at the time prohibited a player from being removed during an inning except in the case of an injury.

27 “Current Sporting Gossip,” Kansas City Times, October 11, 1889: 2.

28 At the Association Meeting in November, St. Louis and Brooklyn got into a dispute over the next league President. Kansas City left the league after backing the losing candidate.

29 “Hastings Hustling,” Lincoln Evening Call, February 24, 1890: 2.

30 “Catcher Hoover Suspended,” Kansas City Times, June 5, 1890: 2.

31 “Now Manager Manning,” Kansas City Star, June 2, 1890: 1. A few days later it was reported that Hackett was seriously ill with “partial paralysis of the brain.” While he recovered enough to return home to Holyoke, Massachusetts, he never fully recovered. He died on August 1, 1898.

32 Charlie Hoover and Hattie Hoover were a known couple in Lincoln throughout his time in Lincoln. The Lincoln Evening Call reported in June 1888 that they were to be married in the fall (“The Courts,” June 27, 1888: 3.), and on October 15, 1890 the same paper describes Hoover as “[enjoying] the distinction of being the husband of Hattie Hoover” (“Through the Police,” pg. 5). Other reports from the time indicate she was his mistress.

33 “Mere Mention,” Nebraska State Journal, July 6, 1890: 8.

34 “Chips From the Diamond,” Kansas City Times, July 8 1890: 2.

35 “Notes of the Game,” Nebraska State Journal, August 15, 1890: 2.

36 “The Figures in Full. Record of the Western Association Players,” Nebraska State Journal, October 8, 1890: 2.

37 “Personal,” Lincoln Journal Star, October 6, 1890: 4. No record of a marriage has been found.

38 “A Turmoil of Love,” Lincoln Evening Call, December 13, 1890: 1, and “Sins and Sinners”, Lincoln Evening Call, December 16, 1890: 1. Other papers from Lincoln at that time also carried the story.

39 “Weep for His Departure,” Nebraska State Journal, February 21, 1891: 7.

40 “Police Court Pickups,” Nebraska State Journal, August 2, 1891: 7.

41 “Baseball Gossip,” The Record-Union (Sacramento, California), May 13, 1891: 3.

42 “Caught on the Fly,” Lincoln Journal Star, May 21, 1891: 1.

43 “Right off the Bat,” Omaha Daily Bee, August 2, 1891: 16.

44 The biography for Charlie Hoover in “Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2” (David Nemec, U. of Nebraska Press, 2011, pg. 231) describes the advertisement, but the author was unable to locate the original. Nemec reports he had a second surgery after being released by Cincinnati in 1893.

45 “The World’s Champion,” Butte (Montana) Weekly Miner, February 9, 1893: 6.

46 “After Hours,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, May 7, 1893: 2.

47 “Charley Hoover Loses His Temper in the Jacksonville Game,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), July 27, 1895: 3.

48 “Charlie Hoover Signed Conditionally,” Omaha Daily Bee, April 16, 1892: 2.

49 “Memphis Club Shy on Guarantee,” Nashville Banner, June 28, 1902: 1.

50 “Sham Meyers’ Independents,” Shreveport Times, April 24, 1903: 3.

51 “Notice,” Shreveport Journal, August 1, 1904: 8.

52 “Board of Health,” The Caucasian (Shreveport, Louisiana), March 5, 1905: 8.

Full Name

Charles E. Hoover

Born

September 9, 1865 at Mound City, IL (USA)

Died

February 27, 1905 at Shreveport, LA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.