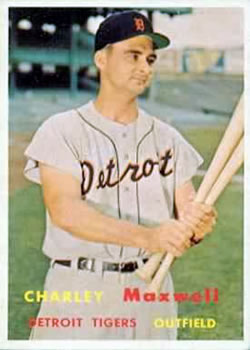

Charlie Maxwell

Charles Richard “Charlie” Maxwell, the popular outfielder of the Tigers from 1955 to 1962, often called “Paw Paw” by fans, writers, and broadcasters, was one of Detroit’s best power hitters. A lefthanded batter who averaged .264 lifetime, Charlie hit 148 home runs and batted in 532 runs in a major league career lasting from 1950 to 1964.

Charles Richard “Charlie” Maxwell, the popular outfielder of the Tigers from 1955 to 1962, often called “Paw Paw” by fans, writers, and broadcasters, was one of Detroit’s best power hitters. A lefthanded batter who averaged .264 lifetime, Charlie hit 148 home runs and batted in 532 runs in a major league career lasting from 1950 to 1964.

But the Lawton, Michigan, native first earned his reputation as a “Sunday Slugger” when he hit four home runs in four successive official at-bats in a Sunday double-header against the New York Yankees at Briggs Stadium (later Tiger Stadium) on May 3, 1959.

Yet Maxwell’s quadruple “Sunday punch” in 1959 was only his most famous highlight. In addition to 148 home runs–133 of which he hit as a Tiger–Charlie blasted another 131 round-trippers while working his way up through the minor leagues from 1947 to 1953.

In 1949, for example, playing for the Roanoke, Virginia, Red Sox, Boston’s affiliate in the Class B Piedmont League, Maxwell won the circuit’s Triple Crown. He led the league in batting at .345, in hits with 164, in home runs with 29, and in RBI with 112. Charlie had played for Roanoke the previous season, averaging .294. In 1948 his 124 hits included 22 doubles, nine triples, and 12 home runs, to go with 65 RBI. He was one of Roanoke’s most popular players.

On May 25, 1949, fans in Roanoke saw one of the most exciting games ever played at local Maher Field. According to the Roanoke Times, “Home Run Charley” came to the plate in the ninth inning with two outs and runners at first and second. Trailing 13-4 after six innings, the “Rosox,” the club’s popular nickname, rallied and scored four runs in the seventh and five more in the eighth, while holding the Newport News Dodgers to one run.

Maxwell was already 3-for-5, including a double, two runs scored, and four RBI. With a crowd of over 1,400 screaming for a hit, Charlie, fulfilling the fans’ greatest hopes, belted a towering home run over the right field fence and clinched the 16-14 victory. According to the Roanoke Times, “The crowd went wild!”

Forty-five years later, in 1994, Maxwell’s great season was commemorated by his induction into the Salem-Roanoke Baseball Hall of Fame.

Standing 5’10” and weighing 185 in his prime, with close-cropped brown hair, blue eyes, and a winning personality, Maxwell had the powerful arms and strong wrists of a long ball hitter. A team player, he never failed to give baseball an all-out effort.

Proving his Triple Crown season was no fluke, Maxwell excelled at Birmingham of the Double-A Southern Association in 1950. Hitting .320, he produced 16 doubles, seven triples, 25 home runs, and drove in 85 runs–despite missing several weeks with a broken shoulder.

The Barons lost to Nashville in the playoffs, four games to one, but Maxwell slammed four postseason home runs–a performance that won a late-season promotion to Boston.

Born in the southwestern Michigan town of Lawton on April 8, 1927, the son of Tom and Isa Maxwell, Charlie grew up in the heart of his state’s grape-growing region. The youth, one of three children, often helped with chores at home or in the fields. Shy and quiet, Charlie was well liked by his schoolmates.

As a teenager Maxwell played high school basketball and baseball for Lawton. During the 1944 and 1945 seasons, he became a good pitcher and a tough hitter for the Schoolcraft Bears (renamed the Ramona Bears in 1945) of the semipro Kalamazoo City League.

During the spring of 1945, Maxwell–who paid his way by working on the university’s grounds crew–starred on the mound for Western Michigan, then a baseball powerhouse. That September, during the last year of World War II, Charlie was drafted into the Army. He served two years in the Quartermaster Corps.

Signed by the Boston Red Sox, Maxwell began his pro baseball career in Roanoke in 1947. But after two games he was sent to Wellsville, New York, of the Class D PONY League. There he produced a good rookie season, hitting .354 with 17 home runs and 79 RBI. Once a hard-throwing pitcher, Maxwell, helped by manager Tom Carey, switched to the outfield, worked on his hitting, and made the league’s All-Star team.

As a result, the Michigan native spent two productive seasons with Roanoke, averaging .294 in 1948 and .345 in 1949. His fine ’49 season in Roanoke won him a late-season promotion to Scranton of the Double-A Eastern League, where he hit .250 in seven games. Following his .320 season in 1950 with Birmingham, Maxwell received the call by Boston on September 20. But the Red Sox outfield was set with the incomparable Ted Williams in left field, Dom DiMaggio, who batted .328 in 1950, in center, and Al Zarilla, who hit .325, in right. Charlie got into three games and went hitless in eight at-bats, although he walked once and scored a run.

The 1951 season in Boston wasn’t much better for Maxwell. He played in 51 games, mainly as a late-inning defensive replacement for Williams, or as a pinch-hitter (he went 7-for-31). One of the club’s few young players, he averaged only .188 but hit three home runs. In 1952 his Red Sox average dipped to .067 (1-for-15).

The lefthanded pull hitter found it tough, he later explained, to hit well when he couldn’t play regularly. Maxwell recalled finding little acceptance from Boston’s veteran players. The way they saw it, rookies were a threat to take someone’s job.

Charlie played part of 1951 and all of 1952 for Louisville of the Triple-A American Association. After hitting .255 with four homers in 40 games for the Colonels in 1951, Maxwell hit .282 with 21 homers in 1952. Following a 1-for-15 stint with Boston in September, he asked to spend 1953 at Louisville. There the Michigan native produced a stellar season, batting .305, slugging 23 home runs, and driving in 107 runs.

In 1954 Maxwell began the season as Boston’s left fielder. But in mid-May, when Ted Williams returned to the lineup after recovering from a broken collarbone, Charlie rode the bench. Averaging .250 in 104 at-bats (he was 12-for-45 as a pinch-hitter), he failed to connect for a home run and drove in only five runs.

Boston sold Maxwell’s contract to the Baltimore Orioles in November 1954. The following spring, Baltimore used Charlie in four games (he was 0-for-4) before waiving him. On May 11, 1955, Detroit purchased his contract.

The move to the Motor City was Maxwell’s first big break. His career illustrates that a good player must be blessed with good timing. In other words, a good player must be with the right team, with the right combination of players, and with the right manager in order to have the opportunity to achieve success.

Maxwell was platooned in Detroit’s outfield in 1955, alternating with veteran Jim Delsing, a lefthanded hitter who averaged .239 with 10 homers and 60 RBI, and rookie John “Bubba” Phillips, a righthanded batter who hit .234 with three home runs and 23 RBI. Still, Maxwell outhit his competitors, averaging .266 with seven homers and 18 RBI in 55 games. Later, he built a reputation for Sunday slugging. On July 31, 1955, Charlie hit his first-ever Sabbath blast at Fenway Park against Boston’s Frank Sullivan.

But by 1952, Detroit’s tradition-rich franchise had fallen on hard times, finishing last in the eight-team American League with a dismal 50-104 season. Starting in 1953, the Tigers’ front office began bringing in new, and often younger, players–the most famous being 18-year old flychaser Al Kaline, a “bonus” rookie who jumped from Baltimore’s sandlots to the majors.

The infield of manager Fred Hutchinson–who took over from Red Rolfe halfway through the 1952 season–featured slugger Walt Dropo at first base, smooth Johnny Pesky at second, youthful Harvey Kuenn, who hit .308 in his first full season as a Tiger, at shortstop, and third baseman Ray Boone, a good fielder and tough hitter acquired from the Indians in an eight-player trade on June 15, 1953. The outfield featured veterans like Bob Nieman in left, Jim Delsing in center, and Don Lund in right, with good-hitting Steve Souchock as a reserve. Catcher Matt Batts worked with a staff that included veteran righthander Ned Garver, who injured his pitching arm in 1952 after going 20-12 for the last-place St. Louis Browns in 1951 and was never quite as good again. Garver paced Detroit with an 11-11 mark. Southpaw Billy Hoeft compiled a 9-14 record, and lefty Ted Gray was 10-15. The Tigers finished sixth with a 60-94 record, 40.5 games behind the pennant-winning Yankees.

In 1954 Hutchinson’s Tigers climbed a notch to fifth, finishing 43 games out of first with a 68-88 ledger. But the speedy Kaline, a great defensive outfielder with a strong and accurate throwing arm, hit .276 and drew flocks of fans into Briggs Stadium. Rookie Bill Tuttle, another speedster who, like Kaline, batted righthanded and played exceptional defense, hit .266. Delsing, the veteran lefthanded hitter, moved from center to left field and averaged .248.

Meanwhile, Harvey Kuenn, who played every game at shortstop for the second straight year, continued to sparkle at the plate with a .306 mark. Harvey, another fan favorite and the AL’s Rookie of the Year in 1953, paced the league in hits for the second straight year with 201. Ray Boone, who batted .295, topped the Tigers with 20 four-baggers and 85 RBI. Former bonus rookie Frank House, a lefthanded hitter in his first full season with Detroit, and Bob “Red” Wilson, a righthanded batter who arrived in a trade with the White Sox, handled the catching. Big Walt Dropo’s production fell off: the 6’5″ 220-pounder batted .281 but hit only four home runs. Wayne Belardi alternated with the slow-footed Dropo at first base, hitting 11 homers and averaging .232.

When Maxwell arrived in 1955, Kaline was enjoying a career year, leading the league with a .340 average, turning into a power hitter with 27 home runs and 102 RBI, and mesmerizing Tiger loyalists of all ages with his batting and fielding heroics. Boone tied with Boston outfielder Jackie Jensen for the AL lead with 114 RBI. The former Cleveland infielder, whose exciting presence now caused Detroit fans to chant his name, “Boooooone” when he came to the plate, batted .284 and slugged 20 homers. Smooth, consistent Harvey Kuenn produced another fine season, rapping 190 hits, including a league-high 38 doubles, averaging .306, and producing 62 RBI from the leadoff position. Also, 6’4″ Jack Phillips, a veteran righthanded hitter acquired from the Pirates, averaged .316 while seeing part-time duty at first base. Lefthanded batting Ferris Fain, a former two-time batting champion with the Athletics, hit .264. But Fain struggled on bad knees, and after 64 games, Detroit shipped him to Cleveland. Lefthanded hitting Earl Torgeson, purchased from the Philadelphia Phillies on June 15, became Detroit’s first baseman. In lefty-friendly Briggs Stadium, the graceful Torgeson hit .283 with nine four-baggers and 50 RBI.

Detroit was developing better pitching. Righthander Frank Lary, in his first full season as a Tiger, topped the moundsmen with a 14-15 record. Ned Garver produced a 12-16 ledger. Billy Hoeft enjoyed his best season to date in a Tiger uniform, fashioning a 16-7 record. Also, veteran righthander Steve Gromek, who arrived from Cleveland in the Boone trade of 1953, provided experienced leadership and a 13-10 mark.

Under new manager Bucky Harris, the Tigers finished in fifth place with a 79-75 record. Lefty Al Aber, the Cleveland castoff, topped the relief hurlers with 39 appearances, going 6-3 and earning three saves. Werner “Babe” Birrer, a righthander from Buffalo, New York, hurling his first major league season, appeared in 36 games (he started three) and compiled a 4-3 mark with three saves.

Maxwell, who averaged .266 while platooning in his first year as a Tiger, became an outfield regular by producing an All-Star season in 1956. The hard-working lefty hit a career-best .326, ranking fourth in the league. While handling left field in good fashion, he slugged 28 home runs–fifth highest in the circuit, and a new record for Detroit lefthanded batters–and drove in 87 runs.

In 1956 Detroit again finished fifth, but the club improved to 82-72. For the season, Detroit’s lineup was stable. Backed by Jack Phillips, Earl Torgeson played first base and averaged .264 with 12 homers and 42 RBI. Frank Bolling, the sure-handed second baseman in his second season with Detroit (he spent 1955 in the military service), hit .281 with seven homers and 45 RBI. Kuenn, who had made two straight All-Star teams at shortstop, again batted leadoff and averaged .332 with 12 homers and 88 RBI. Boone anchored third base and hit a career-best .308 with 25 four-baggers and 81 RBI. In right field, Kaline, developing into a future Hall of Famer, batted .314 with 27 homers and produced a career-high 128 RBI. Tuttle, often called–along with Kaline–a “speed merchant” by broadcaster Van Patrick, played a smooth center field and hit .253 with nine circuit blasts and 65 RBI. And in left field, Maxwell, the small town Michigan lad who made the big time, became the newest star in the lineup.

On the mound, Bucky Harris’ staff featured a “Big Three”: Frank Lary led the league with 21 wins and 294 innings pitched, while losing 13 times. Paul Foytack, a big righthander pitching his first complete season as a Tiger, went a career-best 15-13 (he matched that record in 1958). Billy Hoeft was 20-14. Aging Steve Gromek, who first pitched in the big leagues in 1941, posted an 8-6 mark. Former Tiger righthander Virgil “Fire” Trucks (6-5), back from stints with the Browns and the White Sox, made spot starts. Al Aber (4-4 with seven saves) again topped the bullpen crew, this time with 42 appearances.

In the meantime, Maxwell earned new nicknames during his splendid summer of 1956. At least one sportswriter dubbed him the “People’s Choice” because, on top of his good hitting, he hustled on every play. Fans enjoy anticipating and seeing sluggers connect for homers, but they also want to see athletes play the game in all-out fashion. Maxwell satisfied them on both counts.

The popular Maxwell won yet another moniker. In 1952, two years after they were married, he and Ann built a new home in Paw Paw, half a dozen miles from his hometown of Lawton.

“Ol’ Paw Paw,” his rooters from southwest Michigan would shout, “Give us a hit, Paw Paw,” “Hit it out of here, Paw Paw,” and the like. Many of those folks had seen Maxwell pitching, slugging, and making catches in the outfield since his teenage years.

Charlie often gave a pregame show for the fans, especially on Saturdays when the Tigers hosted kids from the “Knothole Gang.” Shagging fungoes in left field, he would grin, clown around, and catch the ball behind his back or between his legs. Sometimes he would toss a ball to the kids, providing memories that endured long after the game was forgotten.

In 1957 Maxwell continued his solid diamond performance, hitting .276 with 24 homers and 82 RBI. Under new manager Jack Tighe, Detroit improved to fourth place, the “first division” in the eight-team AL. The Tigers finished with a 78-76 record, but they trailed the first place Yankees by 20 games.

Tighe’s lineup was stable, except Boone, who endured an offseason with a .273 mark and 12 homers with 65 RBI. Ray, slowing a bit at age 33, played mostly first base. Former bonus rookie Reno Bertoia, who averaged .275 with four homers and 28 RBI, and the newly acquired Jim Finigan, who hit .270 with 17 RBI, split the duties at third base. Kuenn and Bolling completed the double-play combination, while Kaline, Tuttle, and Maxwell manned the outfield posts. Hard-throwing righthander Jim Bunning, a future Hall of Famer now hurling his first full season with Detroit, led the AL with 20 victories and 267.1 innings pitched. Bunning lost eight games, mostly by close scores. But Frank Lary slipped to 11-16, Duke Mass went 10-14, Paul Foytack was 14-11, and Billy Hoeft finished at 9-11.

As Ray Boone recalled in 2005, “We had good hitting and good fielding, but we didn’t have enough good relief pitching.”

Still, Maxwell proved to be a solid clutch hitter. “I was a tougher clutch hitter late in the game,” he recollected. “Sportswriter Hal Middlesworth told me that I led the team in game-winning hits in 1956 and 1957, even though other guys hit for higher averages.”

But in 1958 Paw Paw’s numbers declined: he connected for 13 home runs and drove home 65 runners. The Tigers slipped to fifth place, finishing with a 77-77 record, and Bill Norman replaced Tighe as pilot a third of way into the season.

Norman’s infield was rebuilt, but not improved. Boone, relegated to a reserve role, hit .237 in 144 at-bats, mostly at first base. Reno Bertoia, the Canadian who was now in his sixth season with Detroit, again split duties at the “hot corner.” Ozzie Virgil, a third-year infielder acquired from the New York Giants, also played third. But Bertoia, playing 86 games, hit only .233, while Virgil, Detroit’s first player from the Dominican Republic, played 49 games and hit .244.

The remainder of the infield was solid. Lefty Gail Harris, obtained from the New York Giants in the offseason, started at first and batted .273 with a team-high 20 homers and 83 RBI. Steady Frank Bolling averaged .269 but hit 14 homers and contributed 75 RBI. Harvey Kuenn, moved from shortstop to center field, improved his hitting to .319 (his average fell to .277 in 1957), adding eight home runs and 54 RBI. Veteran infielder Billy Martin, obtained in a 13-player trade with Kansas City, took over at shortstop and batted .255. With Frank House traded to the Athletics, Red Wilson, a good defensive catcher who showed little power, hit a career-high .299.

Maxwell’s .272 average was again solid, and his 13 four-baggers and 65 RBI both ranked fourth on the team. Kaline, the shining star in right field, averaged .313. A perennial All-Star by age 23, Al saw his home run total fall to 16, but he contributed a club-best 85 RBI. With Kuenn now patrolling center, the Tigers had an established outfield. Gus Zernial, the 6’2½” slugger who had spent most of his nine previous seasons with the Athletics in Philadelphia and then Kansas City, hit .323 in 66 games. Gus contributed five home runs but led the league in pinch hits, going 15-for-38 for a sizzling .394 mark.

In Maxwell’s first four years in Detroit, despite fine individual performances by players like Al Kaline, Harvey Kuenn, Ray Boone, Frank Lary, and Jim Bunning, the Tigers peaked with fourth place finishes in 1956 and 1957. But in the meantime, the players developed a strong camaraderie.

Speaking in a 2001 interview, Charlie called the Tigers a close-knit team:

“Players treated each other equally in Detroit. All of the guys were close. It didn’t matter how much money you made. We all felt close. Lots of times following an afternoon game, several guys would go out together and have dinner.

“Bill Murray was a fan that a lot of us knew. Bill had a home on Lake Michigan near Port Huron. On an off day, some of us would take our wives and children and drive out to his place. We’d swim or go boating or just relax and enjoy ourselves. Detroit was a great place to play ball when I was a Tiger.”

But in 1959, after several years of improving performances, Detroit stumbled to a dismal start. On May 2 the Tigers fell into the American League cellar with a 2-15 ledger. One day later the Bengals erupted and won a double-header from the New York Yankees.

In the first game, Maxwell delivered a run-scoring single and, in his last at-bat, a solo home run. In the nightcap, Paw Paw clouted a two-run homer in the first inning, walked in the third, blasted a three-run home run in the fourth, and slugged a solo round-tripper in the seventh.

Charlie knocked in two runs in the first game, which Detroit won, 4-2, and he accounted for six runs in the second, which the Tigers won, 8-2. On that historic Sunday, the People’s Choice went 5-for-7 with four home runs and eight RBI.

Maxwell’s electrifying performance tied him with old-timer Bobby Lowe, who set the record with the Boston Nationals in 1894, and six modern players as the only major leaguers to date who hit four home runs in four successive official at-bats.

Ted Williams had achieved the feat most recently, in May 1957. Besides Williams, the select company of sluggers featured Ralph Kiner (twice), Jimmy Foxx, Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg, and Bill “Swish” Nicholson.

However, following the 1958 season, when the 31-year-old Maxwell hit only 13 homers, Detroit’s management concluded he was no longer effective. On March 21, 1959, as spring training began, the Tigers traded for 34-year-old Cleveland slugger Larry Doby.

The American League’s first black player in 1947, Doby was selected for the Hall of Fame in 1998. While the lefthanded power hitter clubbed 253 home runs for the Indians and White Sox, he was nearing the end of his sterling career. Doby failed to connect for a single four-bagger with Detroit.

Frustrated, Detroit had fired manager Bill Norman on May 2, following a 15-3 loss to the last-place Washington Senators. The Tigers quickly hired veteran manager Jimmy Dykes, 63, who was coaching for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Meanwhile, Maxwell had been riding the bench with a .182 mark (4-for-22) and six RBI. Worse, he had hit only one home run–a pinch-hit three-run shot in the season’s opener, which Detroit lost to Chicago, 9-7, in 14 innings.

Looking for a quick fix, Dykes talked to his coaches. Then he listed Maxwell in left field, switched Doby to right, and moved Kaline to center. Kuenn, the regular center fielder, was injured after being hit on the elbow by a pitch.

Maxwell remained in left field and Kaline in center for the rest of the season. Kuenn was shifted to right, and Doby, with a salary of over $30,000 (third high for Detroit, behind the salaries of Kaline and Kuenn), was sold to the White Sox on May 13.

On May 3, a sunny Sunday afternoon at the storied stadium on the corner off Michigan and Trumbull Avenues in Detroit, the temperature stood near 70 degrees. Maxwell was slated to bat third. In the first inning against Yankee righthander Bob Turley, Charlie stepped in with no outs and two runners aboard. Longtime third baseman Eddie Yost, acquired in the offseason from Washington, had led off with a walk, and reserve first sacker Larry “Bobo” Osborne also drew a base on balls. Paw Paw promptly singled, driving in Yost, and but Detroit led, 1-0

In the second inning New York scored two unearned runs off Frank Lary, the “Yankee Killer” who then owned a 16-5 lifetime record against the Bronx Bombers. Detroit came back to tie the score, 2-2, in the bottom of the inning when Frank Bolling slammed a bases-empty home run.

Leading off in the third, Maxwell grounded out to second base. But Kaline doubled, and shortstop Rocky Bridges, who also arrived from Washington in the Yost trade, singled him home. Detroit led, 3-2, and manager Casey Stengel replaced Turley with righthander Don Larsen.

Batting in the fourth against Larsen, Maxwell took a called third strike as Detroit failed to score. Neither team tallied again until Detroit came to bat in the seventh.

Homer #1: Leading off, Maxwell drove a Larsen fastball deep into the upper deck in right field, boosting Detroit’s lead to 4-2.

Lary held the Yankees scoreless for the rest of the game, scattering eight hits and improving his 1959 record to 2-2.

Batting in the third slot in the nightcap, Maxwell came up in the first frame with Detroit ahead, 1-0, after a leadoff homer by Yost and a single by Osborne.

Homer #2: Maxwell faced righthander Duke Maas. The former Tiger delivered a fastball, and Charlie drove it into the lower deck in right field, scoring two runs.

Stengel replaced Maas with righthander Johnny Kucks. But Detroit scored another run on a ground out by Red Wilson, upping the lead to 4-0. By this time the partisan crowd of 43,438 was cheering and applauding the Tigers’ stellar play, particularly Maxwell’s two round-trippers.

In the third inning Kucks pitched around the Michigan native, walking him. Detroit failed to score in the third, but the Yankees scored one run in the top of the fourth on a wild pitch by Tiger southpaw Don Mossi. Detroit led, 4-1.

Homer #3: In the fourth Maxwell came up against Kucks with two outs, Osborne at first and Yost at third. Kucks challenged Charlie with a fastball. The southpaw belted the pitch into the center field bleachers, a home run that carried over 400 feet. After Kaline popped out, the Tigers led, 7-1.

New York scored again in the seventh, thanks to a double by pinch-hitter Andy Carey and a single by Clete Boyer. The scoreboard read: Detroit 7, New York 2. Slamming the door on the Yankees, Don Mossi won the game and upped his record to 1-1 by scattering eight hits.

Homer #4: In the bottom of the seventh, Maxwell faced seldom-used Zack Monroe. When the righthander tried to fool Maxwell with two straight change-ups, Charlie drove the second pitch deep to right center, well over the 415-foot marker.

“Each blow brought a bigger roar from the crowd,” Hal Middlesworth observed in the Detroit Free Press, “and there was pandemonium when ‘Old Paw Paw’ connected again in the seventh with the bases empty and Zack Monroe doing the pitching.”

“When you’re playing in a game, you’re focused on what you’re doing,” the modest former Tiger told Jack Moss of the Kalamazoo Gazette 40 years later, on May 2, 1999, “plotting your maneuvers on the next play, and being alert to every challenge.

“The home runs just seemed to come, but the big thing to me was that we won both games and gained some respectability.”

Maxwell’s performance jump-started Detroit’s season. The Tigers climbed to within a game of first place by June 20, winning 32 of 46 games. But thereafter, injuries struck, and the club’s hitting and pitching was inconsistent. Detroit finished in fourth place with a 76-78 record, 18 games behind the pennant-winning White Sox.

Maxwell, although batting .251, led the Tigers with 31 home runs and 95 RBI. Both figures represented major league bests for him.

How valuable was Maxwell in his prime? For Detroit, superstar Al Kaline made the greatest contribution. Clutch-hitting Ray Boone, who gave the Bengals four straight 20-homer seasons and tied for the AL lead with 116 RBI in 1955, and Harvey Kuenn, who hit for a higher average but had fewer home runs and RBI, matched or exceeded Maxwell’s value.

But from 1956 through 1960, the five years he played as a Tiger regular, Maxwell’s overall averages included .272, 24 homers, and 82 RBI. Rare for a power hitter, he drew bases on balls almost as often as he fanned–averaging 71 walks and 75 strikeouts per season. During those five years he struck out only 20 more times than he walked.

Charlie recalled, “I used to run back to the dugout after I struck out. I did it for the fans. I wanted to get off the field as quickly as possible and let them see another hitter come up to bat.”

Paw Paw led the Tigers in four-baggers for three years, hitting 28 homers in 1956, 24 in 1957, and 31 in 1959, when his 95 RBI also led the team.

Twice, in 1956 and 1957, he made the American League All-Star team, though not as a starter. In the 1956 contest, which the National League won, 7-3, Ted Williams played the entire game–par for the course in the 1950s. Maxwell did not get off the bench. In the 1957 contest, which the AL won, 6-5, Maxwell pinch-hit for Detroit pitcher Jim Bunning in the fourth. Charlie singled, giving him a lifetime All-Star average of 1.000.

Defensively, Maxwell led AL outfielders at his position in 1957 and 1960, compiling fielding percentages of .997 and .996, respectively. Considering his salary, which peaked at $26,000 in 1960, Charlie provided more bangs for the bucks than any other Tiger in his years as a regular.

But in 1960 two younger power hitters arrived via trades. Norm Cash, a 26-year-old lefthanded batting first baseman who would go on to stardom in Detroit, averaged .286 and belted 18 home runs. Rocky Colavito, 27, the righthanded slugger and teen idol who was swapped by Cleveland for Harvey Kuenn on April 17, 1960, batted .249 and hammered 35 round-trippers.

Maxwell’s average dipped to .237 in 1960. Still, he connected for 24 home runs and drove home 81 runs, ranking second on the club to Colavito in both categories.

Once again Detroit’s management had doubts about Maxwell’s effectiveness. Thus, for 1961 the Tigers traded Frank Bolling and outfielder Neil Chrisley for four Milwaukee Braves, notably longtime center fielder Billy Bruton, who was two years younger than Maxwell, and righthanded reliever Terry Fox. First-year manager Bob Scheffing shifted Kaline back to right, installed Bruton in center, and shifted Colavito from right to left.

As a result, Maxwell provided mainly pinch-hitting while others enjoyed banner years. In 1961 he played in 79 of Detroit’s 162 games, batting 131 times. Charlie averaged only .229, collecting 30 hits, five of them home runs, and 18 RBI.

Cash led the AL with a career-year mark of .361. “Stormin’ Norman” also cracked 41 home runs, breaking Maxwell’s 1959 club record for lefthanders, and came through with 132 RBI. Kaline became the AL Comeback Player of the Year, batting .324 with 19 homers and 82 RBI. In addition, Colavito batted .290, blasted 45 home runs, drove in 140 runners, and topped AL outfielders with 16 assists.

In 1962, when the trade deadline neared, Maxwell and his salary appeared expendable. On June 25, after Charlie cleared waivers, the Tigers swapped him to the Chicago White Sox for rookie outfielder Bob Farley–who was batting .189 with one home run. At the time Maxwell, reminiscent of early 1959, was hitting .194 with one homer.

The trade didn’t mean the end of Charlie Maxwell’s career. On the contrary, the Pale Hose, playing in spacious Comiskey Park, boasted few power hitters. Veteran third baseman Al Smith led the team in 1962 with 16 home runs. Center fielder Jim Landis with 15 and left fielder Floyd Robinson with 11 were the other Chisox reaching double digits in homers.

Once established in the lineup on a semi-regular basis, the Michigan native responded in fine fashion. Consider these highlights:

* On Saturday, June 30, Maxwell slugged his first White Sox home run, a three-run blast in the first inning–a blow that paced Chicago to a 7-0 win over Cleveland.

* In a Sunday double-header against Cleveland on July 8, Maxwell helped his team win twice. In the first game, which Chicago won, 6-3, Charlie delivered his now famous “Sunday Punch,” this time with the bases empty. He added two singles in four at-bats. In the nightcap he went 3-for-4 again, ripping a two-run triple to right in the first inning. He added two singles, one for an RBI, and the Sox won, 8-4.

* On Sunday, July 29, Maxwell had his second greatest day as a major leaguer. Like his afternoon of May 3, 1959, this performance came against the Yankees. In the opener Maxwell socked a three-run home run off righthander Ralph Terry. Charlie added a single, but the Sox lost, 7-4. In the second game he blasted two straight solo home runs off righthander Rollie Sheldon, and Chicago won, 4-2. For the day Maxwell went 4-for-7 with three homers and five RBI.

* On Sunday, August 19, Maxwell’s bat helped defeat the Tigers. In the sixth inning of first game of a double-header, with the score tied at 4-all, Charlie hit a grand slam home run. He also cracked a two-run double as the White Sox thumped the Tigers, 11-5. For the game he went 2-for-5 with six RBI. In the nightcap Detroit won, 8-3, behind Billy Bruton’s grand slam home run. Maxwell picked up one single in two at-bats.

Charlie had other big Sundays, but he never could give a good reason for his Sunday slugging. After a Sunday game featuring one of his circuit clouts on May 31, 1959, Charlie smiled and told reporters, “There’s no reason why I do my best hitting on Sunday. I’m just a crowd pleaser, I guess.” Asked on August 19, 1962, why he hit so well on Sundays, Paw Paw replied, “I don’t know. But I sure wish I could find out so I could do it on the other days of the week.”

By the third week of August, Maxwell was batting .352 for Chicago and .290 overall, thanks in part to his 13-game hitting streak (he hit .429 for those games), the team’s longest that year. Charlie’s homer against Detroit was the fifth Sunday round-tripper of 1962 and his 25th on Sundays–since his Sunday records began being kept in 1959.

According to a study by Jeff Kabacinski and Herman Krabbenhoft, Maxwell hit 40 of his 148 home runs, or 27%, on Sundays.

For Chicago in 1962, the 35-year-old Maxwell hit nine home runs in the last three months of the season (he hit 10 in 1962). He played more than 50 games in the outfield and seven more at first base. Charlie averaged .296 (and .271 overall), and he finished with a .440 slugging percentage. Still, the Sox wound up in fifth at 85-77, just behind Detroit and 11 games back of the first-place Yankees.

Maxwell’s success proved short-lived. In 1963 Chicago mainly used Dave Nicholson in left (he hit 22 homers), once more reducing Maxwell to reserve status. The Sox made a season-long run at New York but finally finished second. For the year Charlie played in 71 games, batted 130 times, and averaged .231, including four doubles, two triples, three home runs, and 17 RBI. He struck out 27 times, but he drew 33 free passes.

In early 1964, now in his 14th season as a big leaguer, Maxwell failed to hit in two games as a pinch-hitter. At the end of the third week of May, Chicago released him.

“It was time to hang it up,” he said in 2001. “It wasn’t fun any more. The travel in Chicago was grueling. Because the Cubs were also in town, we’d spend a week at home and a week on the road. The travel and being away from your family got to be old.”

The outfielder returned to Paw Paw, went to work selling die-cast components for automobiles, got involved in a variety of community activities, and stayed active with golf and tennis. Now retired, Charlie and Ann have four children (Charles R., Jeff, Cindy, and Kelly) and 11 grandchildren.

Overall, the personable slugger provided thousands of loyal fans with many thrills at dozens of minor and major league ballparks. He always gave baseball his best effort and he always remembered the fans. That’s why so many people, especially Tiger fans, remember him.

In 1997 Maxwell received the honor of induction into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame. He chartered a bus and took his family to Detroit. Charlie savored the glory of that evening.

During a 1976 interview, the sandlot star and onetime Tiger hero who grew up yearning to make the big leagues and who persevered against long odds, recalled his biggest thrill:

“It was that I was one of the many, hundreds of thousands, I suppose, who have a dream of being a major league ballplayer. With God’s gift and a lot of hard work, I was one of 400 major league players in the country. And for two of those years, I was one of the fifty best.”

Sources

Interviews with Charlie Maxwell, September 1992 and January 2001; Baseball Encyclopedia, Macmillan Publishing, 1990 edition; Pat Doyle’s Professional Baseball Player Database, version 5.0; clippings in Maxwell File at National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Library; stories from Roanoke Times for 1949 season of Roanoke Red Sox; baseball articles in Detroit Free Press for May 1959; baseball articles from New York Times about White Sox games in 1962; Jeff Kabacinski and Herman Krabbenhoft, “Charlie Maxwell The Sunday Slugger,” Baseball Quarterly Review, vol. 2 (1987), pp. 84-98; Lyall Smith, “Was Charley Maxwell A Flash in the Pan?” in Sport, May 1957, pp. 28-29, 70-72; Shodie Nichols, “He Goes to Bat for His Family,” in Good Housekeeping, vol. 144 (April 1957), pp. 69, 161-162, 164, 166.

Full Name

Charles Richard Maxwell

Born

April 8, 1927 at Lawton, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.