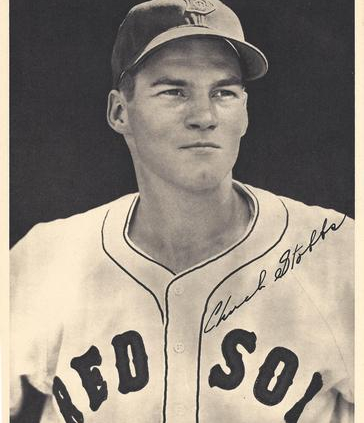

Chuck Stobbs

One of baseball’s original bonus babies, Chuck Stobbs was signed by the Red Sox at the age of 17 and went on to enjoy a 15-year career in major league baseball. The lefthander posted a record of 107-130 playing for teams which often placed low in the standings.

One of baseball’s original bonus babies, Chuck Stobbs was signed by the Red Sox at the age of 17 and went on to enjoy a 15-year career in major league baseball. The lefthander posted a record of 107-130 playing for teams which often placed low in the standings.

He came from an athletic lineage. His father, T. William Stobbs, had been an All-American football player who played the 1921 season with the Detroit Tigers football team. Bill Stobbs didn’t see much action; he was a blocking back who played in seven games, accumulating 60 yards rushing, 16 yards as a receiver, and 30 yards passing.

After his football career, Bill took a position at Wittenberg College in Springfield, Ohio, teaching history but primarily coaching football, basketball, and baseball. Serving in the Navy during World War II, he was stationed in Norfolk and coached the Naval Training Station basketball team.

Chuck’s mother, Elizabeth “Lib” Stobbs, was quite an athlete herself, having played basketball in high school and college. Chuck’s brother Dick remembers, “She was a good athlete and they were quite a team. There is no question but that the players knew that Mother was sitting up in the stands observing and watching what was going on, because she knew the game extremely well, as well as any of the college kids did. Mother and Dad would talk about the game afterward…. Back in those days, they only had one coach — they didn’t have eight like they do now — and she would be his eyes up in the stands, and she had an awful lot to contribute.”

Bill Stobbs went into private business later in life, and did some volunteer coaching on the side. He ran the Old Dominion Peanut Corporation distributorship in Norfolk for many years, until he retired. Lib Stobbs was a homemaker.

Charles Klein Stobbs was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, on July 2, 1929 as the middle of three brothers — Bill Jr., Chuck, and Dick. By the time Chuck reached high school, the family was in Norfolk and he attended Granby High School, where he ranked as an All-State athlete in football, basketball, and baseball for two years running. Dick remembers, “I can’t tell you how many…. There was a tremendous number of schools that wanted him to play football. He was probably a better football player than he was a baseball player. His abilities were probably stronger there. But he chose to go into baseball for whatever reason.”

At a very early age, he and some of his young buddies formed their own team and called themselves the Rinky Dinks. Chuck loved the game, but told his daughter Betsy that if he could have he would have chosen basketball over baseball. He was given a scholarship to Duke, but the money he was offered by the Red Sox was too compelling. Chuck says that both parents were very supportive (he remembers his mother shouting, “Get off the dime!” during his basketball games), but that he made his own decision to get into baseball.

And it was in baseball that Chuck attracted the most attention. The June 7, 1947, Washington Post had termed Chuck “one of the greatest athletes to be developed in the Virginia high schools during recent years” and noted that he’d averaged more than 15 strikeouts a game.

Though primarily a pitcher, Chuck was a first baseman on the Granby High team that played in the 1945 state All-Star game. In June 1946, he pitched for the Eastern Virginia All-Star team, defeating the Western Virginia team, 7-1. He was named the outstanding player of a 1946 All-Star baseball game held in Chicago.

A curious incident occurred at the 1947 Virginia high school championship game. Chuck was pitching for the Granby Comets against the George Washington Presidents of Alexandria and he set down the first six Presidents in order on four strikeouts and two infield plays. A grounder to second looked like a routine 4-3 play to first, but the first baseman juggled the ball. The runner was ruled safe and that riled Chuck’s father, Bill, the Granby coach, who ran out to argue that the first baseman had possession long enough for it to be an out. The plate umpire ejected Bill Stobbs from the game. On the very next pitch, the runner on first broke for second and looked out, but this time the shortstop bobbled the ball. Chuck ran over to argue with the second base umpire that the shortstop was returning the ball to the pitcher when he dropped it. The home plate umpire came out to see what was going on, and Chuck turned and shouted, “I’m arguing with the second base umpire. This is none of your business. Get back behind the plate where you belong.” Chuck had to be restrained by his catcher, and was ejected as well.

A few minutes later, George Washington had the bases loaded and the Granby catcher thought he had a shot to pick off the baserunner leading off first base. The runner broke from third, the first baseman fired home, and the ball got away from the catcher. Granby’s nine-year-old mascot, Chuck’s brother Dick, thought he’d be helpful and threw the ball back to the catcher. The third Stobbs was banned from the bench, and the umpire waved in one more run for GW. All three Stobbses had been ejected in a matter of a few minutes. George Washington won the game 4-3 in 10 innings.

Chuck had caught the eye of Paul Decker, a local American Legion coach and part-time scout and George introduced him to Red Sox scout George “Specs” Toporcer, the man who signed him to a major league contract when Chuck was still 17, in May 1947. After inking the deal for a reported $50,000 bonus, Chuck came to Boston to work out with the Red Sox before being given his first assignment.

A bonus rule at the time provided that anyone signed to a contract for more than $6,000 had to be kept on the 40-man roster for the two seasons following the year he was signed. It was also mandatory that he be kept on the big league ballclub for those two years and not sent out to a minor league farm club. Though he regrets not branching out and playing as many sports as we could, the bonus given to Stobbs was quite a large one at the time.

In his signing year, 1947, Stobbs pitched for the Lynn Red Sox in the New England League, posting a 9-2 record and a 1.72 ERA in 94 innings of work. He appeared in his first major league game on September 15, entering when starter Harry Dorish tired after 7 1/3 innings. Stobbs got the second out of the eighth, but walked a batter and gave up a hit. The Red Sox kept the lead, and won. John Klima, who has studied baseball’s bonus rule, notes that many pitchers in particular suffered under the rule, inevitably idle most of the time they were on the big league bench. The Red Sox had to keep Stobbs on the big league club in 1948 and 1949, the two years after his signing, but were able to farm him out in 1947, the year of his signing. Referring to Red Sox farm director Johnny Murphy, Klima wrote, “Stobbs was extremely lucky that the Red Sox opted to send him to Class-B, where he could compete, build confidence, and actually get competitive innings, knowing full well that he would be rotting in the bullpen when he first came to the big leagues. You look at his career as opposed to Paul Pettit’s and the Red Sox made a wise decision that should be credited. It would have been the farm director’s call.”

Stobbs got his first starting assignment on September 19 and pitched three perfect innings against Washington, and singled his only time up, but the game was called on account of rain after three innings. His first official start came in the first game of a September 23 doubleheader against Philadelphia. He lasted only 1 2/3 innings, driven from the game by four hits, two walks, and a wild pitch. He was charged with three runs and the loss. He ended 1947 with an 0-1 major league record and a 6.00 ERA in nine innings of work.

Stobbs threw only seven innings in all of 1948 and recorded no decisions, with a 6.43 ERA. Though he was eligible for the World Series, the Red Sox hopes ended with the one-game playoff defeat at the hands of the Cleveland Indians.

In 1949 he finally hit his stride — despite the bonus rule costing him a year of seasoning he could have had in 1948. Stobbs started 19 games in 1949 and appeared in seven games in relief. He won 11 and lost six, with a 4.03 ERA, but for the third year in a row walked more than he struck out. At times he suffered from a lack of run support, but at other times benefited from big Boston scores. A particularly nice win came on August 17, though one couldn’t say it was any gem: Stobbs got the complete game win in 10 innings, limiting the Athletics to one run on six hits, but was pitching out of trouble throughout, thanks to the 10 bases on balls he granted.

He walked more than he struck out again in 1950, but won 12 games while losing seven (5.10 ERA) in the course of 21 starts and 11 relief roles. June was quite a month. In his six starts, the final scores were 17-7, 29-4, 8-1, 2-10, 12-9, and 22-14. He left with the lead in the first game (June 4), but pitched only 4 2/3 innings so had a no-decision. He won the second start (June 8), going the distance despite all the time spent on the bench watching the Red Sox set the modern records for runs scored in a ballgame. He also won on June 13, a two-hitter. Next time out, June 18, he took a loss, giving up three runs in the first before retiring a batter; he didn’t make it through three. The 12-9 win on the 23rd was good for the team but Stobbs was long gone when the Sox scored six times in the last two innings. His last start of the month saw another record set for runs scored in a game, this time for the two teams combined. The 22 scored by Boston should have given an easy win to Stobbs, who took the ball after the Red Sox built a 6-0 lead in the top of the first. He retired only two players before he was replaced, after giving up two hits and three walks.

Stobbs had his best year at the plate in 1950, batting .246 (14-for-57), with 12 walks to his credit and nine RBIs. He was a more than adequate fielding pitcher, with a .977 fielding average. At the plate, Stobbs was nothing special. He accumulated 102 hits in 578 at-bats (.176), with 15 doubles his only extra-base hits.

There was a time early in 1951 when it looked as though Stobbs was heading into the Army, but he was rejected twice due to asthma. Stobbs pitched better overall but his last four starts wound up in losses. He finished the season 10-9, with a 4.76 ERA, and was dealt in November to the White Sox. Chicago GM Frank “Trader” Lane sent Randy Gumpert and Don Lenhardt to the Red Sox for Stobbs and infielder Mel Hoderlein. Stobbs had four years of major league experience but was still only 22 years old.

Chuck spent just the 1952 season with the White Sox, with an excellent 3.13 earned run average, but suffering double-digit defeats (7-12). After the season, Chicago traded him to the Washington Senators for Mike Fornieles. Washington manager Bucky Harris really wanted a lefthander. Stobbs played eight seasons with the Senators, with an overall record of 64-89 despite fairly good pitching throughout. He suffered two disastrous seasons (1955: 4-14, 5.00 ERA, and 1957: 8-20, 5.36 ERA), not at all helped by a team that finished last in both years (both times finishing exactly 43 games out of first place).

The biggest headlines from the Washington years came early in his first season when Mickey Mantle slammed a home run off Stobbs that went completely out of Washington’s Griffith Stadium on April 17 and estimated at 565 feet (this figure is often disputed). The storied blast was one of the longest home runs ever hit in major league baseball. Connie Marrero was asked in an early 2008 interview what Stobbs said after he returned to the dugout. Recalling earlier days, Chuck reportedly said, “At least I got to pitch in Yankee Stadium.” Four years later, Stobbs said the experience had made him a better pitcher, at least against The Mick. Just a few weeks after the home run, Stobbs may have thrown another historic pitch. While there is no official record, he is considered by many baseball historians to have thrown the wildest pitch in major-league history during the first game of a doubleheader in Detroit on May 20; the pitch landed in the 17th row. In 1956, Chuck allowed three singles — and not one RBI — in 27 Mantle at-bats. He also won a career high 15 games, but lost 15, too.

Becoming a 20-game loser in 1957 was discouraging. Stobbs lost his first 10 starts, one after the other, and every one of his first 11 decisions. It was June 21 before he won his first game of the year. It wasn’t just hard luck; his ERA was 8.90 after the 11th loss. To make matters worse, he’d lost his last five decisions in 1956. With 16 losses in a row, the Senators pulled out all the stops. They gave him a new uniform number, 13, and gave away a free rabbit’s foot to the first 1,000 fans who came out to “Charm Night” — the June 21 game at Griffith Stadium to see Stobbs square off against Cleveland. A New York firm donated another 1,200 rabbit’s feet and the National Brewing Company distributed 1,000 “lucky coins.” Chuck’s mail contained horseshoes, four-leaf clovers, and all sorts of other talismen. Stobbs struck out eight, allowed seven hits, and walked four. He won the game, 6-3. He went 7-9 for the rest of the season.

Stobbs always started poorly, due to the asthma, but when he dropped his first three decisions in 1958 and found himself at 2-6 by late June, he may not have been surprised to find himself sold to the St. Louis Cardinals during the All-Star break for the $20,000 waiver wire price.

Now in the National League, and used exclusively in relief, he pitched more effectively but won only one game against three losses. After the season, the 29-year-old Stobbs married Jocelyn Johns and the couple maintained a home in Washington. When the Cardinals placed him on waivers in January, no one bit and he was given his release. He signed with Washington as a free agent — and came back wearing eyeglasses. An eye examination had shown a 35 percent deficiency in one of his eyes. The Washington team optometrist said that “Stobbs should have far better perception of the target area.”

Indeed, he threw 90 2/3 innings in 1959 and struck out more than twice as many as he walked (50-24), posting the best earned run average of his major league career at 2.98. He won only one game all year, on May 5. He lost eight. Only seven of his 41 appearances were starts. He was credited with seven saves.

From 1957 through 1959, Chuck had won 12 and lost 17. In 1960, he won as many games as all three years combined, posting a 12-7 record (with a 3.32 ERA.) It was a nice last hurrah in Washington. Stobbs (and the entire Washington team) played in 1961 in Minnesota, when the Senators franchise became the Minnesota Twins. A new expansion franchise was placed in Washington; that team became the Texas Rangers in 1972.

For the Twins, Stobbs started three games, relieved in 21, and went out with a whimper. His last appearance came on August 12. The Tigers were beating the Twins 8-3 after seven full innings. Stobbs gave up two singles, threw a wild pitch, and walked two batters, forcing in a run. That was enough. Four batters, all reached base — and all scored. He finished the year 2-3 (7.46 ERA) and was given his release in October.

Looking back on his 15-year career, there were certainly many good moments but there were naturally regrets as well. It was difficult coming up under the bonus role. “When you’re 18 in the big leagues, you don’t know a hell of a lot,” Chuck said. As far as being a bonus baby, “Yes, I was frustrated. I wore the bench out.” With a little sardonic humor, he says that he finally had to be steered to the pitching mound and told when you come to the circle with the white rubber in it, stop and pitch. He hated the inaction, sitting around, because he felt he wasn’t really contributing to the team, and it was not a good feeling worrying whether his teammates resented him at some level as the bonus baby. After appearing in 459 major league games, with over 100 victories to his credit, it is safe to say that he’d validated the belief the Boston Red Sox had in his talents.

After baseball, he took a position with the Jim Parker Insurance Agency in Silver Spring, Maryland. Chuck broadcast Washington Senators baseball for one year, 1969, the first year Ted Williams managed the team. In May 1970, Chuck took on additional duties when he accepted an appointment as baseball coach at George Washington University. He’d been assistant coach the year before. Early in 1971, he resigned to take a position as pitching coach with the Kansas City Royals baseball academy in Sarasota which he did through 1976. Chuck lost his wife Jocelyn in the early 1970s to a brain tumor and it was a challenge raising four young children — three girls (Betsy, Nancy, and Hasse) and a boy (Charlie Jr.), the oldest of whom (Betsy) was 12 at the time. He later remarried, to Joyce Robinson. Chuck worked with the Indians from 1979 to 1981 and then retired.

Charlie Jr. played some ball in college and currently works for Nike as a product manager traveling the United States and Europe. Betsy’s son Evan Stobbs is a right-handed pitcher and infielder who has already attracted interest from major league scouts and began college at the University of Central Florida in the fall of 2007 on a baseball scholarship. Nancy has three children — Ike, Charlie, and Jocelyn. Hasse has two sons, Austin and Brook, both football players at Sarasota High. Charlie Jr. has four children — Chaz (Charlie), Lauren, Chandler, and Lyndsey. Several are active and talented at sports.

Chuck was diagnosed with throat cancer quite a few years ago and it flared up throughout 2006, though by early 2007 he had begun to prevail in the ongoing battle. Even before the illness struck, he typically declined requests for interviews, being by nature a private man. Chuck is very active in his church and finds comfort there, as he does watching his children and grandchildren develop.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Interview with Dick Stobbs, December 11, 2006.

E-mail communication from John Klima, February 18, 2007 and from Stanley Cohen on July 22, 2011.

E-mail communication from Kit Krieger, February 29, 2008.

Interview with Betsy Stobbs on March 17, 2007. Betsy asked several questions of Chuck and his quotations come from her March 17 discussion with him.

Thanks to Chris Anderson, Denise Holman, and Clyde Metcalf.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Charles Klein Stobbs

Born

July 2, 1929 at Wheeling, WV (USA)

Died

July 11, 2008 at Sarasota, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.