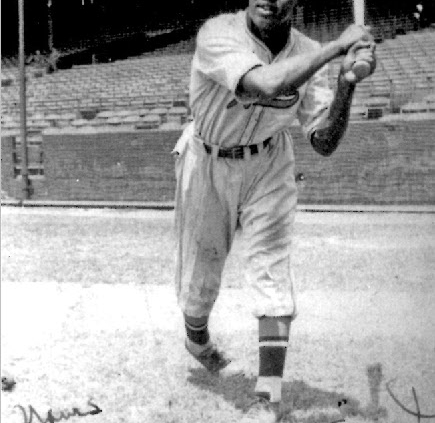

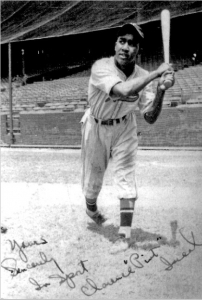

Clarence Isreal

His name was Clarence Charles Isreal. That’s Isreal, not Israel. His name should not be conflated with the country of the Middle East. Most of the newspapers of his time did not grasp that distinction. Consequently, often the misspelling has carried over into subsequent baseball records.

His name was Clarence Charles Isreal. That’s Isreal, not Israel. His name should not be conflated with the country of the Middle East. Most of the newspapers of his time did not grasp that distinction. Consequently, often the misspelling has carried over into subsequent baseball records.

In his six-year professional baseball career, Clarence Isreal spent more than four playing under three managers who now reside in the Baseball Hall of Fame and were well known for their ability to tutor young ballplayers. It was perhaps due to the influence of these men — Ben Taylor, Biz Mackey, and Willie Wells — that Isreal’s lasting fame in life was as a mentor to young men in his community. His two other managers, Dick Lundy and Vic Harris, weren’t run-of-the-mill names, either. Lundy was among the 39 finalists in the 2006 selection process of Negro Leaguers for the Hall of Fame. Harris was one of the most successful managers in Negro League history, with his Homestead Grays finishing first seven times under his guidance. Isreal had plenty of fine examples from whom he could have learned.

The earliest years of Clarence Isreal were spent in rural Georgia. He was born in Marietta, Georgia, on February 15, 1918. His parents, Frank and Violet Isreal, lived on a farm in a place called Big Shanty in an area of Cobb County near Kennesaw. Frank was a sharecropper and railroad worker whose life spanned from 1886 to 1977, and Violet lived from 1891 to 1985; they were wed in 1911.

Georgia was not a lasting part of Clarence’s life. In 1923 Frank and Violet packed up their household and moved to Rockville, Maryland, near Washington, where they hoped their lives would improve. According to the 1920 Census, there were three children in the family at that point — Louise, age 7; Willie May, 6; and Clarence, 2. By the time of the 1930 Census, the family had expanded dramatically. Clarence was now one of nine children, and there was a grandchild in the house as well.1

To feed all these children, Frank and Violet had to work hard, and they took a number of jobs over the years. According to the book Rockville: Portrait of a City, Frank initially worked as a caretaker and handyman at Chestnut Lodge in Rockville. Violet was a housekeeper at Rose Hill Farm in Rockville.2 They also raised some farm animals on their property and grew their own vegetables. Later, Frank was a laborer in a coalyard. He had also been head custodian at Lincoln High School.

Clarence grew up in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Rockville during a period of segregation. He attended segregated schools, including Rockville Colored Elementary School, and graduated from Rockville Colored High School in 1935. Unfortunately, to families of color the city seemed in many ways like a place in the Deep South until well into the midcentury.

Life also was difficult for Clarence in that he had a falling out with his father. The second oldest son, Clarence felt that he was being given too great a share of the responsibility for the household chores. He rebelled and was punished by his father. As a result, he left home for a period and had to fend for himself. He and his father did not reconcile until Clarence was well into adulthood.3

After high school, he played sandlot baseball locally for a few years. A historical marker in Rockville indicated that the first semipro team he signed with was the Washington Royals. In 2018 the year on the marker was being revised, but the team seems to be correct. The Washington Royals traveled up the East Coast to cities like Rochester, New York, and Trenton, New Jersey, to take on all sorts of local arrays, such as YMCA teams. Clarence’s nephew, Jackie Smith, said he believed that Clarence joined the Royals in 1938. Then he started to play at a higher level of semipro ball with the Washington Royal Giants in 1939. The Royal Giants played in Griffith Stadium, the home of the American League’s Washington Senators. The Royal Giants were in the Negro International League, and they were making their debut under that name in 1939. In 1938 the team had been known as the Washington Black Senators. Teammates of Isreal’s on the Royal Giants squad included Rockville pals Mike Snowden and Russell Awkard, Mike’s nephew. Also on the team was catcher Thomas “Babe” Snowden, a first cousin of Mike who came from Sandy Spring, Maryland. Since Mike was a pitcher, there were times when the line score showed a battery of Snowden and Snowden.4

Isreal was a fine ballplayer. His Royal Giants manager, Ben Taylor, who had been a premier player in the Negro Leagues and who would be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, described him as “another Dandridge.” The reference was to Ray Dandridge, who had a Hall of Fame career as a third baseman and who was generally considered, along with Judy Johnson, one of the two best third sackers in the Negro Leagues. Later on, Clarence Isreal and Ray Dandridge became teammates on the Newark Eagles, and Clarence was the one who held down the third-base spot. That’s how good he was. After his death, the Montgomery Journal reported that scouts had said of Isreal: “You just can’t get anything past him at third.”5

Clarence was generally known by his nickname, Pint, which came from his diminutive size. According to the website of the Cobb County (Georgia) Hall of Fame, of which Isreal is a member, he was 5-feet-5; Seamheads.com confirms that height. Originally, the nickname was Half Pint, but it was shortened as people verbalized it and used it with more frequency.

In 1940 Isreal made his debut in the Negro Leagues with the Newark Eagles and was positioned at second base as half of the keystone combination with future major leaguer Buzz Clarkson. He took over from 12-year veteran second baseman Dick Seay, as the 1940 Eagles manager Dick Lundy announced on July 29 that Isreal had been doing such terrific work as an understudy that he deserved the top job.6 According to James Riley’s The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues, although never a spectacular hitter, Seay had been the best defensive second baseman in the Negro Leagues during the decade of the 1930s, so Isreal had beaten out somewhat of a legend.7

Pint had a highly successful rookie season, batting .294 with 32 hits in 32 games, with an on-base percentage of .347. He hit 4 homers, scored 28 runs, and drove in 22 runs. In the annual benefit game against the House of David team, Pint won the contest by hitting a single with the bases loaded to seal the victory for the Eagles, 7-6. The Salisbury newspaper described him as the “home run king on the team,” although that seems to be an exaggeration since by the end of the season three other Eagles had slammed more homers.8

Isreal began 1941 by continuing at the second sack, but a couple of changes were in store for him that year. First, he shifted to third base to make room for Leon Day, mostly known as a pitcher in his Hall of Fame career, but who was versatile on the field and with his bat. That move occurred in September as it was announced that “Clarence Israel [sic], the smooth-fielding infielder, has shifted over to third.”9 Second, his draft board started taking significant interest in him. In August, Isreal was rejected by the draft board on the basis of flat feet and bowlegs, but that was not the end of his concern about military obligations.

The newspapers and the public had a great deal of praise for Pint’s playing ability in 1941. The Washington Evening Star said he was “regarded as the sparkplug of the infield” on the Newark team.10 The Jersey Journal of June 18 stated that “the Eagles built their attack around Francis Matthews, Clarence Israel [sic], and Monte Irvin.” When it came time for the public to select the teams for the East vs. West All-Star Game, Pint came close to securing the second-base slot on the East Team. Ironically, he lost out to an aging Dick Seay, who had moved on to the New York Black Yankees after having surrendered his second-base position with the Eagles to Pint. The top three vote-getting second basemen in the final results were Dick Seay, 182,063 (made the East all-star team); Billy Horne, 179,621 (made the West all-star team); and Clarence Isreal, 179,210.11

In total for the 1941 season, Isreal hit .268 with 42 hits in 44 games, with an on-base percentage of .341. He hit two homers, scored 31 runs, and drove in 17 runs while hitting second in the batting order for most of the season.

After the season, Pint was back in Rockville and was representing his community in a baseball game in mid-September. Along with fellow Newark Eagles player Russell Awkard, Isreal was on the Montgomery County All-Stars, an Afro-American team that played the white All-Stars from Howard County at John C. Howard’s Green Bridge Inn in Maryland. The Montgomery County All-Stars were managed by Robert Lee “Mike” Snowden, from a Rockville family. Mike was the man who had first influenced Pint to start playing baseball seriously, according to Pint’s son Robert.12 Mike became the high-school baseball coach around 1936 after Pint had graduated. When the high-school season ended, Mike Snowden would organize the teenage boys, along with some older youths and adults, and play them against adult teams, giving them the competitive training they needed to advance their skills. According to Pint’s nephew, Jackie Smith, Mike’s team was called the Rockville AC’s.13 Mike also managed a semipro team from Baltimore, so he was well equipped to train the young men in advanced concepts of the game. Mike had assumed the leadership position in the Snowden Funeral Home in 1936 when his father, George, the founder, retired. As of 2019 the Snowden Funeral Home remained a prominent fixture in Rockville.

In 1942 Pint returned to the Eagles and continued to receive praise for his play. In late June the Washington Evening Star declared that “Newark is reported to have one of the finest infields in Negro baseball, with (Willie) Wells at short, ‘Pint’ Israel [sic] at third, Ray Dandridge at second, and Lenny Pearson at first.”14 Isreal’s batting average declined, but he was solid. He hit .208 with 30 hits and 19 walks in 42 games, scored 24 runs, and drove in 15 from the leadoff spot in the lineup. During the summer he learned that he had lost his draft exemption and on August 18 he reported for induction into the US Army.

Isreal was initially assigned to the 54th Aviation Squadron at Mather Field in California, and was reported to be on the Baseball Stars team from that Army Air Force Base near Sacramento.15 After that assignment, he was the player-manager of an Army team in Texas. Subsequently, he was reassigned to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. In 1945 it was reported that he led his team to the Aleutian championships as he hit .450 and was the most feared hitter in the championship series. His Aleutian team topped an Alaskan mainland team in the “Midnight Sun” World Series.16 He was discharged from the Army as a sergeant on November 25, 1945.

Although Pint had shed his military uniform, he decided to take another job connected to national defense. Pint’s personnel record indicates that he worked for the Navy Department from January 4 through March 28, 1946, when he returned to the Eagles.

Perhaps Isreal’s most notable games in 1946 were his first and last. At the opening game of the season, which was played in Newark on May 7, Leon Day tossed a no-hitter. The game was a pitchers’ duel and scoreless until the sixth inning, when Pint tripled to right-center and subsequently scored as the Eagles beat the Philadelphia Stars and Barney Brown, 2-0. Brown gave up only six hits, and Pint had two of them.

On May 30 Pint was part of a fifth-inning rally in the second game of a doubleheader with the Philadelphia Stars at Ruppert Stadium in Newark. He hit a single and scored a run, contributing to a 6-3 Eagles victory. He was the only Eagles player with two hits in the contest.

Pint was at the center of a controversial game which was the second of a twin bill on Sunday, July 21, 1946. The Eagles were playing the Cleveland Buckeyes in the home park of the latter team. The remainder of the game description comes from Effa Manley, the co-owner of the Eagles:

The score was tied 1-1 in an extra inning game. (Leniel) Hooker came to bat and got a hit. Mackey (Biz Mackey, the Newark manager) sent Isreal to run for him. The next man to come to bat was pitched one ball by the Cleveland pitcher and Isreal was called out, due to the fact that Isreal did not tell the umpire that he was running for Hooker. Now, there is no question that the umpire should have been told that Isreal was running for Hooker, and the Eagles were at fault for not doing it; but the penalty in the rule book for such an offense is a fine for the captain or the manager of the team at fault. Under no condition is the runner to be called out by the umpire for this offense. I do not like the team to squabble on the field, but I am sure that no one would expect a manager to take a decision like that without arguing.17

Mackey had done more than argue. He had pulled the Newark team off the field, causing the Eagles to forfeit the game, 9-0. Effa Manley had stood behind his decision.

Overall, Pint’s 1946 regular-season statistics for the Eagles were a .191 batting average with 17 hits and 6 walks in 31 games. He scored 11 runs and drove in 6. Although still mostly a third baseman, he also played part-time in the outfield. At some point during the season, he moved over to the Homestead Grays for one game as the website Seamheads.com credits him with a batting average of .250, chalking up one hit and one RBI for the Grays in 1946. The most likely scenario is that he was loaned to Homestead for one game.

The most important game of the 1946 season for Pint and the Eagles took place on September 4. That was the day on which the Eagles clinched the championship of the National League and assured that they would be playing in the Negro League World Series. The Eagles defeated the Cuban Stars, 17-5. Pint had two hits, both doubles, according to the newspaper write-up, and scored four runs. The account in the Indianapolis Recorder cited Larry Doby as the leading Eagles contributor with five hits in the game, but Pint was the second offensive player mentioned.18

Pint did not play a more crucial part in the Eagles’ 1946 season because in early June they obtained Pat Patterson from the Philadelphia Stars to replace him as the starting third baseman. After that, Pint played utility roles, including some games in the outfield.

In the Negro League World Series of 1946, the Eagles faced the Kansas City Monarchs. In Game One, Pint was the starting third baseman for the Eagles. He had one unsuccessful at-bat before he was injured chasing a pop foul off the bat of Herb Souell into the field boxes along the third-base line; he ended up dislocating his knee. He did not make another appearance until Game Five, which was played in Chicago’s Comiskey Park. In that game he was once again the starting third sacker, and he hit a single in three official at-bats. That was the only contest of the World Series in which Pint played for the entire game.

Going into Game Six, the Eagles were down three games to two and were desperate for a win. One more loss and the Monarchs would be the champions. Pint started the game at third base, walked in the first inning, and moved around the bases to score the Eagles’ first run. The Monarchs had taken a 5-0 lead in the top of the first, but by the time the inning was over, the lead was narrowed to 5-4. The Eagles ended up winning, 9-7. The two-run edge was slim, so every run was important, and Pint had made a significant contribution in the World Series. The victory enabled the Eagles to advance to Game Seven, which they won, although Isreal did not play. He had been removed from the lineup early in Game Six with one official at-bat and no hits, and had been replaced by Pat Patterson; it is quite possible that his knee injury had started bothering him again after he ran the bases.

James A. Riley asserts that Pint played in three games during the 1946 World Series and he got a pinch hit off Satchel Paige in one of them.19 This claim is only partially correct. According to the box scores for all seven games, Pint played in three games but never faced Satchel Paige in any of them. He got his sole hit off Hilton Smith.

Pint must have made quite an impression during his lone game for Homestead in 1946 as he played exclusively for Grays in 1947. He hit .206 in 131 at-bats, according to Seamheads.com. Only five players on the team had more plate appearances, so he was playing regularly. He would later call it “one of the greatest teams I’ve ever seen in my life and that’s including black or white.”20 It is assumed that he was referring to the 1946 version of the Homestead Grays, since two of their biggest stars, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell, had departed by 1947.

There were also times during Pint’s Negro Leagues career when he joined barnstorming teams of Negro League stars. When he was interviewed for an article in the National Institutes of Health Record of July 21, 1978, he recalled, “We used to barnstorm against white teams in various games and most of the time we’d beat ’em.” Pint also asserted, “We felt we were as good as the white players, if not better — and this was our chance to prove it.”21

At a gathering at Glassboro (New Jersey) State College as part of Black History Month in February 1986, Isreal remembered a game against a white all-star team in which the blacks could not hit the ball past the infield, while the whites were clobbering the ball. Pint said: “I couldn’t believe they were that much better than us. It turned out that when we were up, their pitchers were throwing balls that they had put in the refrigerator.”22

In the book Shades of Glory, Lawrence Hogan picked up what really motivated Pint to strive to play well in baseball. He quoted Pint as saying: “I guess the only reason I wanted to play was because I wanted to be good like the rest of the ballplayers. It’s something that gets in your craw. It sticks with you.”23

It was clear that Isreal enjoyed the experience of playing in the Negro Leagues, but what brought it to an end was Jackie Robinson’s breaking into the major leagues. According to Pint’s son Bobby, his father could read that step as the “handwriting on the wall” for the future of Negro Leagues baseball.

Pint’s brother Elbert, also known as Al, had a five-year career in the minor leagues in the Philadelphia-Kansas City A’s system as Organized Baseball began to integrate. He, too, was an infielder. Elbert hit .301 in 622 games from 1952 through 1957 with a break in 1955 when he did not play. In 1952 he led the Class-B Interstate League in hitting with a .328 batting average. In his book Brushing Back Jim Crow, Bruce Adelson details the struggles of Afro-American minor leaguers in the 1950s as they grappled with lingering discrimination in the South, despite Jackie Robinson’s already having broken through barriers at the major-league level; the entire discussion about the South Atlantic League in one chapter of the book is devoted to Hank Aaron and Al Isreal.24 Al played in the Negro Leagues for the Philadelphia Stars in 1950 and, along with his brother Pint, on the Homestead Grays in 1947. Al was born in 1927 and died in 1997.

Pint’s wife, Florence, was originally from Leavenworth, Kansas. They were married during World War II while Pint was in the Army. In addition to raising their children, Florence toiled as a domestic worker in houses located in places like Bethesda and Silver Spring. Florence died in January of 1975.

Pint and Florence raised three sons, Michael; Robert (aka Bobby), and Clarence Jr. (aka Butch). Michael died in 1997, Bobby in 2007, and Butch in 2014.25

Pint and Florence also had a daughter, Karen, who did not survive through childhood because she suffered from leukemia. In 1958 Satchel Paige staged a benefit game at McCurdy Field in Frederick, Maryland, to raise money to assist in the care of Karen. Pint and his nephew, Jackie Smith, both played in that game.26

Isreal had a fulfilling life after his time in the Negro Leagues. He continued to play baseball with a segregated team in Rockville, the Rockville Legionnaires, sponsored by the American Legion. In 1949 the Frederick News reported Pint as playing for that team in a game against the Frederick Legion contingent.27 At one point the Rockville team had Russell Awkard as player-manager plus Pint, Elbert, and Dewey Isreal as players.

Isreal’s first experience with the civilian part of the federal government was holding an offseason job as a laborer with the Public Health Service from November 1946 to May 1947. In those days, PHS was in the Federal Security Agency, which was the forerunner of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

From 1948 to 1973 he worked for the National Institutes of Health. He began as an animal caretaker, but for most of his career at NIH he was a lab technician.

Pint offered his baseball prowess to the athletes at the NIH Club. He became player-manager of their baseball team. In 1951 he helped them tally 45 wins and take home the honor of being the best among the Washington area’s 233 teams. His NIH group was the first integrated baseball team in Montgomery County.28 He also continued to apply his baseball skills as a coach in semipro baseball and an umpire for baseball and softball games.

Beyond the ongoing investment of his time in baseball activities, Pint wanted to do even more things for others. In 1968 he and schoolteacher Russell Gordon co-founded the Black Angels Boys Club in Rockville, an organization that served throughout Montgomery County.29 He collected donations from his colleagues there to support the work of the Boys Club. Pint was active in the Big Brothers program to help young boys who needed guidance. He volunteered with FISH (For Immediate Sympathetic Help), an organization that provides food, transportation, and other services to the needy and elderly. He gave volunteer hours to two day-care centers in Rockville and with the Head Start Program in Lincoln Park, and was active in his church. At the Jerusalem United Methodist Church, he sang in the choir and, showing his ever-present love for children, taught Sunday School.30

Pint’s longtime friend Michael Johnson shed some additional light on his attributes. Johnson recalled:

“When I was young, Pint got me started in basketball officiating. Pint observed that in the local area, there were no Afro-Americans in officiating roles. He went to the Rockville officials to plead for change, and things changed. If you met him, you would love him. He saw things in people that they didn’t see in themselves. Every kid who played baseball knew his philosophy was ‘If you had two strikes on you, you had to swing on the third pitch if it was anywhere near the plate.’ In other words, never miss an opportunity. Pint would also say: ‘Religion is first, family second, everything else next.’ If Pint knew you, he was at the game (to be there in support of you). He knew more about you than your parents. It didn’t matter what sport you played, football, basketball, or baseball, if you were a friend of Pint, he would be at the game to cheer you on.”31

Billy Gordon, a basketball star at Rockville’s Richard Montgomery High School and the University of Maryland-Eastern Shore, was drafted by the Seattle Supersonics, but a knee injury ended his NBA career before it started. After basketball, he became an administrator in the Montgomery County public school system. He is also the father of former major leaguer Keith Gordon. He said, “Pint was one of my mentors and my heroes.”32

Most Americans of a certain age have heard numerous conspiracy theories concerning the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. One of those theories involves Pint Isreal as a witness to Kennedy’s autopsy. Healthy skepticism should be employed as the origin of this theory is revealed. Returned to Washington, Kennedy’s body was taken to the Bethesda Naval Hospital, directly across the street from the NIH campus where Isreal was known to have worked. There is a file with Clarence Isreal’s name on it in the collection of the National Archives pertaining to Kennedy’s assassination.

The claim comes from the book Murder From Within: Lyndon Johnson’s Plot Against President Kennedy, by Fred T. Newcomb and Perry Adams. The book was written in 1974 and only about 100 copies were distributed then as a self-printed manuscript. The version relevant to Isreal was the first full publication of the book in 2011. By that time Fred Newcomb was 82 years old and ailing, and Perry Adams was deceased. The passages pertinent to Pint are contained in the foreword by Fred Newcomb’s son, Tyler Newcomb. Around 2004, he learned via a document posted online by the National Archives that Clarence Isreal had told NIH biologist Janie Taylor that his brother (unnamed and deceased) had been on duty as an orderly in the autopsy room in the Bethesda Naval Hospital on November 22, 1963, when Kennedy’s body was present. Newcomb assumed that the relevant brother was Elbert (Al). Supposedly, there was one point in the process at which many people were forced out of the room, and one doctor manipulated the bullet wounds in some way. Elbert allegedly witnessed this as it happened. Later in the foreword, Tyler Newcomb wrote that a man named Jim Lavin had spoken with Mrs. Elbert Isreal, who verified that her late husband had been on duty in the hospital’s morgue on the night of November 22. According to this account, Mrs. Isreal added that Clarence Isreal had also been on duty there that evening.33 However, neither Jackie Smith nor Michael Johnson had ever heard mention of Pint having had a job at the Bethesda Naval Hospital.

Elbert Isreal, like Pint, was employed by NIH, but no evidence has been found to show that Elbert was employed by the Bethesda Naval Hospital. On the other hand, Dewey Isreal, Pint’s older brother, was known to be a Bethesda Naval Center employee in 1963. An issue of the Naval Medical Center News of 1963 places Dewey on the Center’s intramural softball team in July of that year, but he was a cook, not an orderly.34 It must be remembered that Pint was reporting on a deceased brother who supposedly was in the autopsy room. It is not known when Pint spoke to Janie Taylor about this story, but Pint died in 1987. Janie Taylor reported the story to the representative of the Kennedy Assassination Records Review Board in 1995.35 Elbert Isreal was alive until 1996 and Dewey Isreal lived until 1999. The facts just don’t line up.

The Clarence Isreal file at the National Archives contains 16 documents, all of which are perfunctory personnel records. They range from job applications to assignment transfers to reports of minor injuries to statements of minor organizational changes. One document contains a signed oath of allegiance by Isreal to the US Constitution, along with an affidavit that he did not advocate the use of force to overthrow the government; that document was dated October 13, 1947. The materials suggest that the staff of the Kennedy Assassination Records Review Board did their assigned duty in trying to accumulate information about Pint that might link him in some way to the Bethesda Naval Hospital or the assassination, but nothing in the file succeeds in doing that.

Pint Isreal died of a heart attack on April 12, 1987, at Shady Grove Hospital in Rockville. He is buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Silver Spring, Maryland, along with his wife, Florence.

In February 1988, the city of Rockville named a park after Pint. A plaque marking the dedication of the Clarence “Pint” Isreal Park hangs on the outside of the Lincoln Park Community Center, next to the entrance to the parking lot for the park. Fittingly, the park contains a baseball field, along with other amenities, such as a picnic area and playground equipment for the younger children.

James Coyle, a Rockville councilman in 1988 and later the mayor, was present for the dedication of the Isreal Park. Reflecting on the ceremony, Coyle said, “It was an honor to take part in the dedication of the park in the name of this man who was such a positive influence in the Lincoln Park community.”36

To close the story of Pint Isreal, it is perhaps fitting to use his own words. When asked if he had any advice for future generations, his reply was, “Love God, have faith, and love thy neighbor as thyself.”37

Acknowledgements

Gary Ashwill, moderator of Seamheads.com.

Sheila Bashiri, preservation planner, City of Rockville.

James Coyle, former mayor and councilman, City of Rockville.

Irene Curry, daughter of Mike Snowden and cousin of Russell Awkard.

Bob Golon, member, Society for American Baseball Research.

Billy Gordon, Montgomery County public school system.

Burt Hall, former director, Rockville Department of Recreation and Parks.

Khali Isreal, grandson of Pint Isreal.

Michael Johnson, friend of Pint Isreal.

Mark Kibiloski, Rockville Department of Recreation and Parks.

Peerless Rockville staff.

Jackie Smith, nephew of Pint Isreal (son of Pint’s sister Beatrice).

George Snowden, nephew of Irene Curry.

Richard Cuicchi, member, Society for American Baseball Research.

Wayne Stivers, member, Society for American Baseball Research.

Sween Library (Rockville) staff.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com; the Negro Leagues database at seamheads.com; “Negro Leaguers Who served With the Armed Forces in WW II,” at cnlbr.org; various newspapers; and the following:

Luke, Bob. The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2011).

Abstract of interview of Eileen McGuckian with Violet Isreal and Willie Mae Isreal Carey on September 27, 1983, in files of Peerless Rockville, the historical society of Rockville.

Undated tribute document to Clarence Isreal in files of Peerless Rockville.

File with Title “Medical Isreal, Clarence” in Box 3 of Miscellaneous Files of JFK Assassination Records at National Archives, College Park, Maryland; stack location 650L1/67/19/6.

Notes

1 The children were: Louise, age 17 (F); Willie May, 16 (F); Dewey, 13 (M); Clarence, 12 (M); Goldie, 9 (F); Frank (Mack), 7 (M); Beatrice, 5 (F); Elbert, 2 (M); Violet, infant (F); and Barbara Shelton, 1 (F), Frank Isreal’s granddaughter. Frank and Violet became the parents of three additional children following the 1930 census, as Eileen McGuckian in her book Rockville: Portrait of a City, reported that there were 12 children in the Isreal family. That number was confirmed by Clarence’s son, Robert, in a 2004 interview, in which he stated that there were six boys and six girls. The two additional brothers were Freddie and James. The additional sister was Irene. Also see oral history interview by Shelby Spillers, preservation planner, City of Rockville, with Bobby Isreal, son of Pint, on March 17, 2004 — located in files of Peerless Rockville, the city’s historical society.

2 Eileen McGuckian, Rockville: Portrait of a City (Franklin, Tennessee: Hillsboro Press, 2001), 102.

3 Author’s telephone interview with Michael Johnson in April 2018.

4 Washington Evening Star, May 26, 1939; Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, May 31, 1939.

5 Montgomery Journal (Chevy Chase, Maryland), April 20, 1987.

6 Jersey Journal (Jersey City), July 29, 1940.

7 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 706.

8 Salisbury (Maryland) Times, August 21, 1940.

9 Jersey Journal, September 9, 1941.

10 Washington Evening Star, May 28, 1941.

11 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 171.

12 Spillers interview with Bobby Isreal.

13 Author’s telephone interview with Jackie Smith of Fort Washington, Maryland, in May 2018. Jackie Smith is a nephew of Pint Isreal.

14 Washington Evening Star, June 28, 1942.

15 Sacramento Bee, March 27, 1943.

16 Baltimore Afro-American, August 18, 1946.

17 Pittsburgh Courier, August 10, 1946.

18 Indianapolis Recorder, September 14, 1946.

19 James A. Riley, 409.

20 Rockville Gazette, April 22, 1987.

21 NIH Record, July 21, 1978.

22 Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, February 28, 1986.

23 Lawrence Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of Afro-American Baseball (Des Moines, Iowa: National Geographic Books, 2007), 3.

24 Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor League Baseball in the American South (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999), 83-97.

25 Butch and his wife, Denise, had three children: Nayo Isreal, Omari Isreal, and Kimberly Nash. Bobby and his wife, Pamela, also had three children: Khali Isreal, Hasani Isreal, and Marjani Isreal. Michael’s marriage ended in divorce, and they did not have children.

26 Author’s telephone interview with Jackie Smith of Fort Washington, Maryland, May 2018.

27 Frederick (Maryland) News, June 16, 1949.

28 NIH Record, July 21, 1970.

29 Montgomery Journal, April 20, 1987; Rockville Gazette, April 22, 1987.

30 Author’s telephone interview with Michael Johnson, April 2018.

31 Ibid.

32 Voice message response left by Billy Johnson on author’s telephone, May 2018.

33 Fred T. Newcomb and Perry Adams, Murder From Within: Lyndon Johnson’s Plot Against President Kennedy (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2011), xv.

34 National Naval Medical Center News, Volume 19, 1963.

35 Newcomb and Adams.

36 Author’s telephone interview with James Coyle, January 2018.

37 Document with title “The United Black Cultural Center Presents ‘Let’s Reminisce with Montgomery County’s Black Baseball Players’ Dedicated to Clarence ‘Pint’ Isreal 6/26/1987,” located in the Clarence Isreal folder at Peerless Rockville.

Full Name

Clarence Charles Isreal

Born

February 15, 1918 at Marietta, GA (US)

Died

April 12, 1987 at Rockville, MD (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.