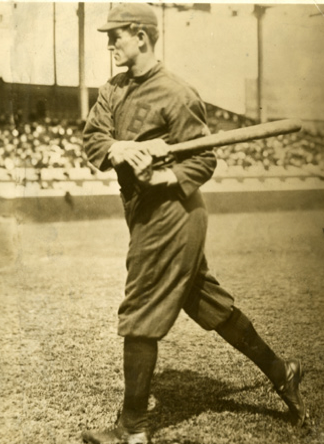

Clarence Kraft

Over time, Clarence “Big Boy” Kraft was probably the greatest power hitter to play for the 1914 Boston Braves. Looking at the records of the major leagues, one would never know it. Even though he played for one of the most memorable teams in history and would become one of the most prolific power hitters in the game, his time with the 1914 Boston Braves was so fleeting and had such little impact on the Braves’ fortunes that it would be easy to overlook his three brief appearances in uniform. However, starting in the months after his stint with the Braves and extending 44 years beyond, Kraft had a significant impact on the sport and on the lives of many people.

Over time, Clarence “Big Boy” Kraft was probably the greatest power hitter to play for the 1914 Boston Braves. Looking at the records of the major leagues, one would never know it. Even though he played for one of the most memorable teams in history and would become one of the most prolific power hitters in the game, his time with the 1914 Boston Braves was so fleeting and had such little impact on the Braves’ fortunes that it would be easy to overlook his three brief appearances in uniform. However, starting in the months after his stint with the Braves and extending 44 years beyond, Kraft had a significant impact on the sport and on the lives of many people.

Clarence Kraft was born on June 9, 1887, in Evansville, Indiana, on the same farm on which his father was born.1 The first of John and Anna Kraft’s five children, he grew up in Evansville and was deeply involved with athletics, playing baseball, basketball, and ice hockey and running track.2 He also showed an early interest in automobiles and after a brief time in business college, went to work selling and repairing cars.3

On the baseball diamond Kraft was a dominant force, both on the mound and at the plate. It was his success as a pitcher on the local sandlots that initially drew the attention of professional baseball. In 1910, at the age of 22, Kraft made his professional debut with the local Evansville team, a member of the Class B Central League. After one game Evansville sent him to McLeansboro of the Class D Southern Illinois League. McLeansboro overwhelmed the rest of the league, going 20-5. The league folded on July 11 and McLeansboro joined the stronger Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (Kitty) League two weeks later.4 The Class D Kitty League had re-formed in 1910 after being defunct for two years and was enjoying a resurgence in interest through the first 60 games. McLeansboro and Vincennes were added to the league and a second 60-game season began.5 The McLeansboro team continued its dominance over the opposition in this second season, going 40-18 and being the only team in the league with a winning record. Despite playing just 51 games in the league as a pitcher and outfielder, Kraft tied for the league lead in home runs with four. He made more of a mark on the mound with a 13-2 record, the best winning percentage in the league.

Kraft’s success was noted throughout baseball. In January 1911 Toledo of the Class A American Association drafted him from McLeansboro.6 The Cleveland Naps of the American League were also interested in Kraft, primarily as a pitcher, and they secured his rights from Toledo and took him to spring training. The jump to the big leagues was too much for Kraft and the Indians returned him to Toledo, which then also released him. Kraft caught on with Flint of the Class C Southern Michigan Association.7

With Flint Kraft continued to pitch and play the field. Once again he paced his league in home runs, this time with 19. On the mound he was not as stellar, posting a 6-12 record. He returned to Flint for the 1912 season. In July Kraft clouted eight home runs in nine days, and Cleveland came calling again, purchasing the rights to both Kraft and a teammate, Billy Hunter.8 Once again the Indians changed their minds. New Orleans of the Class A Southern Association signed Kraft and optioned him to Clarksdale for yet another season in the low minors, this time the Class D Cotton States League.

On the mound Kraft had his ups and downs in 1913, winning seven games and losing seven. He pitched his best game as a professional for Clarksdale, hurling a one-hitter against Meridian.9 He continued to hit and when the league folded in August, New Orleans reclaimed Kraft. Kraft made a couple of pitching appearances, his final stints on the mound, but made an impression with the bat. He hit a home run that was announced as the longest ever hit at Pelicans Stadium in New Orleans.10 He finished the season with a .362 batting average, prompting Sporting Life to call him the Southern League’s “best natural slugger since the days of Joe Jackson.”11

Entering the 1914 season, life was as much business as baseball for the major leagues and Clarence Kraft. Nashville of the Southern Association purchased his contract from New Orleans for $400.12 Less than two weeks later, the Brooklyn Superbas of the National League drafted Kraft, paying Nashville $1,500.13 In April the Superbas released Kraft to the Boston Braves. On May 1 Kraft made his debut in the major leagues, coming in as a replacement for first baseman Butch Schmidt. Batting against future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard, he singled. He pinch-hit twice after that, on May 11 and May 15, and then his career in the major leagues ended.

For someone no longer in the major leagues, Kraft continued to make a splash. Boston released him back to Brooklyn and the Superbas then tried to send him back to Nashville. Kraft opposed the decision and went to the Base Ball Players’ Fraternity for help.

The Base Ball Players’ Fraternity, an early union formed in 1912 to help protect major-league players, had met with the National Commission, baseball’s governing body, after the 1913 season with suggestions for changes. The commission, faced with the threat of a third major league, the Federal League, had worked to appease the Fraternity and implemented many of the suggested changes. One of them, that a player being optioned or released from a major-league team be first offered to Double-A teams before being sent to a lower classification, was the source of Kraft’s discontent. The Newark Indians of the Double-A International League had claimed Kraft but the National Commission ruled that Nashville had put in a claim first. Kraft refused to report to Nashville and went to Newark to play.14

The conflict continued until the Fraternity threatened to strike over the issue. Faced with the potential of a work stoppage, Superbas owner Charles Ebbets offered Nashville $1,000 to withdraw its claim to Kraft.15 Nashville agreed, making $2,100 in profit from Kraft without his ever setting foot on the diamond for the club.

Kraft finished out the 1914 season with Newark and began 1915 with the team. The Federal League had relocated its Indianapolis franchise to Newark in 1915, and the presence of a major-league team forced the movement of the Newark International League to Harrisburg in July. For the season, Kraft posted a .307 batting average and led the league with 24 triples.16

Kraft continued his team-hopping in 1916, signing with Louisville of the Double-A American Association. In June he was traded with two other players to Milwaukee of the same league but all three refused to report, asserting that they should receive bonuses before signing with Milwaukee. The argument was settled and all three players joined Milwaukee.17

Over the course of Kraft’s three seasons at the Double-A level, he performed solidly but not spectacularly. He was strictly a first baseman during this time and as he entered his late 20s, his contractual difficulties coupled with his performance did not bode particularly well for his return to the majors. When Wilkes-Barre of the Class B New York State League purchased Kraft for the 1917 season, it seemed as if his career was on a decline. Still, he hit .311, his highest season batting average since 1913, and tied for the league lead in home runs with seven. The Wilkes-Barre team was a powerful one and Kraft once again belonged to a championship squad, his first since McLeansboro.

In 1918, with the US now in the World War, many minor leagues shut down, including the New York State League. Kraft joined the Fort Worth team in the Class B Texas League. He was on his way to another successful season at the plate, hitting .308 in 70 games, but was drafted to serve in the Army in June. As more players joined the war effort, the Texas League was forced to cease operations weeks later.

Kraft used his automotive experience to his benefit and to his country’s. He joined the 309th Motor Transport Corps and spent six months serving in France. He returned from the war to his home in Missouri, where he married his girlfriend, Dorothy Goessling. Soon afterward they moved to California to be closer to Kraft’s sister but then went to Texas after Fort Worth signed Kraft yet again.

Fort Worth had the best record in the Texas League in 1919 but lost the playoff series to Shreveport. The following season, Fort Worth devastated opponents, topping the standings by 23 games over the second-place Wichita Falls squad, and was crowned champion. During this time, Kraft contributed to the team’s success but not in a large way. In 1919 he hit .275 with 11 home runs. In 1920, those numbers dropped to .258 and six. The batting average was the lowest of his career as was his .359 slugging percentage. Before the 1921 season, the Texas League was reclassified as a Class A league. The season that should probably have been the culmination of a mostly lackluster career turned out to be the genesis of a rejuvenation that put Kraft among the greatest minor-league home-run hitters of all time.

Signs that Kraft was a better ballplayer than he had been in recent years appeared early in the 1921 season. On April 23 against Wichita Falls, he went 5-for-5, hitting a single, a double, and three home runs. In one game, Kraft had hit half as many home runs as he had in 151 games the previous season.

Kraft never slowed down and when the season concluded, Fort Worth was once again champion of the Texas League. Kraft set league records in hits (212) and total bases (376). He led the league in runs scored (132) and won the batting title with a .352 average, almost 100 points higher than he had hit the season before.

Fort Worth’s stranglehold on the Texas League continued into 1922. Since losing the playoff series to Shreveport in 1919, the Panthers had won both halves of the season in 1920 and 1921, eliminating the need for a playoff to determine the champion. In 1922 they swept the season again. Once again Kraft led the league in runs batted in (131) and home runs (32) while batting .339.

The 1923 season was almost an exact reprise of the season before. Fort Worth took the championship and Kraft led the league in home runs, again with 32. He hit .324 and his slugging percentage of .589 was identical to his percentage in 1922.

Going into the 1924 season, it seemed as if Kraft and the Panthers were unstoppable. A few years before Kraft had appeared to be on his way out of professional baseball. Now he was a top power hitter for one of the best minor-league teams in the country. Then, incredibly, both Fort Worth and Kraft got even better.

In 1924 the Panthers won 109 games while losing only 41. They finished 30½ games ahead of second-place Houston in claiming their fifth straight league championship. In May Kraft went on a tear similar to the one he had gone on in Flint a decade before, clouting eight home runs in nine games. He set league records with 196 runs batted in, 414 total bases, and 55 home runs. (The RBI record was still the standard in the Texas League as of 2013.) Kraft batted .349, slugged an incredible .713 and led the league with 150 runs scored.

Despite being at the top of his game and though Fort Worth offered him a two-year contract at $10,000 a year, Kraft, then 37 years old, decided to retire from baseball at the end of the 1924 season to pursue his automobile business. Fort Worth wasn’t the only team interested in keeping Kraft in the game. He rejected an offer to return to the major leagues. The Cincinnati Reds wrote Kraft to see if he would be willing to join the Reds for the 1925 season. Kraft responded that technically he was still on Fort Worth’s reserve list and that after seven years in Fort Worth, he doubted that any team could provide terms that would interest him in leaving.18

Although Kraft would not play again, the Cats were eventually able to draw him back to the diamond. Eight years after he last stepped on the playing field, Kraft returned as president of the Fort Worth ballclub.19 When the club was struggling with financial difficulties, Kraft stepped in and was able to utilize his business acumen to solidify the Cats’ financial standing. He returned to his car dealership and worked there until 1942. With World War II causing a scarcity of automobiles, Kraft ran for political office that year and was elected county judge. He was re-elected in 1944 and 1946 and retired from the position in 1948. As a judge, Kraft strove hard to curb juvenile delinquency and established stringent criteria for county probation officers.20

In the winter of 1957, Kraft suffered a stroke. He then contracted pneumonia. In March 1958 Kraft suffered a heart attack that claimed his life at the age of 70. He was survived by his wife and three children. Despite being a bit player in the drama of the Miracle Braves, Clarence Kraft went on to have an illustrious career and become a legend in his own right.

This biography is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Fort Worth Star Telegram, March 26, 1958, 1, 4.

2 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, comp., “1900 United States Census and National Index,” FamilySearch (Online: Intellectual Reserve Inc., 2009), <http://www.familysearch.org/>, accessed {February 2010}.

3 Fort Worth Star Telegram, op. cit.

4 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1977).

5 J. Foster, ed., Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide (New York: American Sports Publishing, 1911), 239.

6 Sporting Life, January 11, 1911, 12.

7 Sporting Life, April 22, 1911, 3.

8 New York Times, July 21, 1912, 7.

9 Sporting Life, July 5, 1913, 32.

10 Sporting Life. August 15, 1913, 23.

11 Sporting Life, September 27, 1913, 23.

12 Nashville Tennessean, September 6, 1913, 7.

13 Sporting Life, November 15, 1913, 6.

14 Scott Longert, “The Players’ Fraternity,” Baseball Research Journal 30 (Society for American Baseball Research, 2001), 42-43.

15 New York Times, July 22, 1914, 11.

16 Minor League Baseball Stars, Vol. II (Kansas City: Society for American Baseball Research, 1985), 64.

17 Sporting Life. July 1, 1916, 12.

18 Correspondence, Clarence Kraft player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

19 Unattributed newspaper clipping dated August 11, 1932, found in Kraft player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

20 Fort Worth Star Telegram, op. cit.

Full Name

Clarence Otto Kraft

Born

June 9, 1887 at Evansville, IN (USA)

Died

March 25, 1958 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.