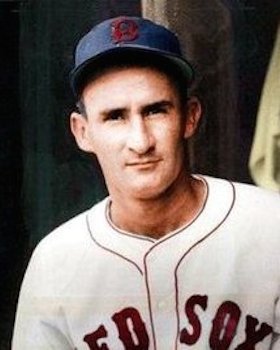

Clem Hausmann

In the history of major-league baseball, there have been two players named Hausmann. Both of them debuted in April 1944, played in 1945, and then returned to the majors for one final year in 1949. They were not related in any known way; New York Giants second baseman George Hausmann was born in St. Louis, and Red Sox and Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Clem Hausmann in Houston. What are the odds?

In the history of major-league baseball, there have been two players named Hausmann. Both of them debuted in April 1944, played in 1945, and then returned to the majors for one final year in 1949. They were not related in any known way; New York Giants second baseman George Hausmann was born in St. Louis, and Red Sox and Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Clem Hausmann in Houston. What are the odds?

One of five major leaguers named Clem, Clemens Ray Hausmann was born on August 17, 1919. His father was Clemens Leo Hausmann (1899-1970), a blacksmith born in Wisconsin, and his mother was Mississippi native Rhoda Estelle (Bond) Hausmann. The 1920 census shows young Clem and his parents living with his grandfather, William Hausmann, who worked as a molder in an iron foundry. According to the 1940 census, his father was still a blacksmith, and the family included two younger daughters, Mary Jane and Shirley Ann.

Clem attended parochial schools at first, with his first seven years at Immaculate Conception and then St. Anthony’s Apostolic School in San Antonio and Houston’s Milby High School. Hausmann pitched in high school and for the Houston Balshaw Grocers and the 1936 American Legion state championship team.

Before going into professional baseball, Hausmann had pursued another calling while at St. Anthony’s. He told the Associated Press that “not for a million dollars” would he consider playing baseball professionally. Felix R. McKnight wrote that “the youngster, now only 16, says he is growing up to be a Catholic priest—not a big-league pitcher…he has consecrated his life to the priesthood and has merely sandwiched in baseball between six years at St. Anthony’s College in San Antonio…two more years and he will enter a seminary…’I wouldn’t care if the New York Yankees wanted me,’ quoth Clem, ‘I’m going to be a priest.’”1

Later in 1936, he pitched against a Jesuits team. In the American Legion junior baseball Texas-Louisiana regional series, Hausmann pitched the Houston team to an 8-7 win over the New Orleans state champion Jesuit High Blue Jays, though the deciding game went the Jesuits’ way, 11-2.2 The Houston team was coached by Lawrence Mancuso, brother of veteran big leaguers Gus and Frank Mancuso.

Hausmann’s pro career began after his 1938 high school graduation. His friendship with the Mancuso family led to his signing with the Refugio (Texas) Oilers in the Class-D Texas Valley League.3 “Who sent me there?” he replied to sportswriter Ed Rumill. “I went on my own. That is, I went with Leon Mancuso, whose brothers Gus and Frank are now in the majors.”4 He worked in 39 games, with a 16-13 record and a 4.59 earned run average. In a game against the Taft Cardinals, he struck out 16 batters, his career high.

George Hausmann played the 1938 season in the Texas League, too, batting .355 in 557 at-bats for Corpus Christi. Face-to-face matchups between the two Hausmanns have not been compiled, to our knowledge.

In 1939, Clem Hausmann started the season with the Greenville (Alabama) Lions in the Class-D Alabama-Florida League. He was 3-5 with a 7.11 ERA, but it was written that he was “denied a trial because of his lack of height and heft.”5 He was said to be just 130 pounds at the time he was released. President Milton Price of the Class-D West Texas-New Mexico League Abilene Apaches was looking for someone to help his last-place team at midseason. He remembered hearing of Hausmann, learned he was a free agent, and wired him the money to come to Abilene. Hausmann won his first five games, striking out 47 batters in his first 45 innings, walking only nine, and allowing only four earned runs.6 He was said to have a superb breaking ball, and was nicknamed “Mickey Mouse” by his teammates.

Hausmann finished the half-season 11-6 (3.64) in 19 games for the Apaches/Borger Gassers (Abilene moved to Borger on July 9). And it was Amarillo that finished in last place. (As it happens, Greenville finished in last place in the Alabama-Florida League.) The Borger Gassers were Hausmann’s team for 1940 and 1941 and he turned in back-to-back 19-win seasons. Borger finished fourth in 1940 and second in 1941.

Despite a 19-11 record in 1940, Hausmann turned in a poor 5.80 ERA; in 1940 he was 19-9, 3.10. Thoughts of the priesthood had clearly faded in his mind, and were certainly gone by the time he married Margaret L. Dodson on March 21, 1941. In April 1942, they welcomed their first child, an eight-pound girl.

His improved record in 1941 may have been due to some coaching he received; pitchers in this era often were just on their own and never had any significant help. “Wilcy Moore helped me with the Borger club,” he said a few years later. “He was the only man on the team who knew anything about pitching. The others were all kids, like myself.”7

It wasn’t the priesthood, but Hausmann had to work in the offseasons and appreciated that baseball was easier: “It’s a picnic compared to some of the things I’ve worked at. For a while I used to shoot oil. That means when a well stopped producing, I’d coax it along by planting and firing off nitroglycerin. I’d rather get hit with a line drive than drop a bottle of nitro.”8

In December 1941, the Texas League’s Dallas Rebels bought Hausmann’s contract. He reported to 1942 spring training with Dallas. On April 25, he was optioned to the Montgomery Rebels in the Class-B Southeastern League, where he was 15-11 with a 2.78 ERA for the pennant- and playoff-winning Rebels. Hausmann was recalled to Dallas for the spring of 1943.

He started the season with the Newark (New Jersey) Bears, however. He was 1-0 in two games, spending most of the season with the New York Yankees’ Kansas City Blues farm team. He was 14-14 (4.02) for last-place Kansas City, his best game perhaps a one-hitter on August 1 (albeit in seven innings.)

In the November 1 minor-league draft, the New York Giants had the first selection and they picked Phil Weintraub. The Boston Red Sox had the second pick and they chose Clem Hausmann. Pitching coach Frank Shellenback worked with him in spring training, trying to help him develop a change of pace and to better disguise his pitchers. He was said to throw “with a wrist snap similar to [sic] style Smokey Joe Wood employed when pitching for the Sox more than three decades ago. And while his fastball is not impressive to watch it is apparently of the sneaky type which fools hitters.”9 Just before the season began he was asked to report for his military draft physical on April 16.

Hausmann’s major-league debut came in relief on April 28. The visiting Philadelphia Athletics held a 5-4 lead after eight. Manager Joe Cronin summoned Hausmann to take over – and he pitched seven scoreless innings, the ninth through the 15th, when Athletics’ shortstop Ed Busch singled off Hausmann’s leg, another ball dropped into short right field as Bobby Doerr and right fielder Ford Garrison “got their signals mixed,” and Woody Wheaton singled in the go-ahead run.10 Hausmann had pitched impressively, but bore the loss. After three more relief stints, he got his first start on May 19. He pitched a full nine innings, allowing just two runs. The Red Sox won in the bottom of the 12th, but it was Mike Ryba who was the pitcher of record and got the win.

His first win was in the second game of the May 28 doubleheader. Again, he worked nine innings and gave up just two runs. This time, the Red Sox had scored four times and Hausmann got the complete-game win. He won four in a row and was 4-1 after beating the Yankees by a 4-1 score on June 11. Then he lost five starts in succession. The Red Sox were truly in a pennant race in 1944 and they couldn’t afford to keep sending Hausmann out there, so he was moved back to the bullpen. He had just two more starts, but pitched creditably with a 3.42 earned run average in 137 innings over 32 games. The team ERA was 3.82, largely thanks to 18-game winner Tex Hughson’s 2.26.

Hausmann’s 1945 season stats were similar in many regards – he pitched in 31 games and 125 innings as opposed to 1944’s 32 games and 137 innings. Of his games, he started 12 in 1944 and 13 in 1945. He was 5-7 instead of 4-7. His WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) was nearly identical, 1.518 and then 1.528. Once more he lost his first decision, then won four in a row, before piling up enough losses to outnumber his wins. In 1945, however, he was more hot and cold. He threw his only two major-league shutouts, in back-to-back starts – June 14 in Philadelphia and June 19 against the Yankees at Fenway Park. Both were 1-0 games and both were three-hitters. The “unsung slinger” then saw his ERA balloon to 5.86 by mid-August, before bringing it down to 5.04 by season’s end.11 That was the big difference – more than a run and a half higher in 1945 as compared to 1944.

With so many star players coming back from military service to the postwar 1946 Red Sox, the team didn’t feel it needed Hausmann. On December 8, at that year’s winter meetings, the Red Sox sent him to the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels in part payment for first baseman Glen “Rip” Russell.12

Hausmann’s statistics for 1946 reflected the opposite of what one might have expected – pitching for the Triple-A Angels, he was 2-3 (5.09) but after being sold outright to Double-A Nashville on June 27, he was 0-8 (with a similar 5.20 ERA).

The next five seasons, he was back in Triple A; the International League’s Buffalo Bisons acquired his contract in January 1947. The first three years, he pitched for manager Paul Richards. In 1947 the team finished fourth, in 1948 it finished sixth, but in 1949, the Bisons finished first, though losing in the playoffs to Montreal. Hausmann’s won/loss record improved each year (8-12, 14-11, and 15-7), though his earned run average worsened each year (3.52, 3.92, and 4.61).

In 1949 he had one last shot at the majors – though he worked only one inning. On October 2, 1948, both Hausmann and IL batting champ Coaker Triplett were sold to the Philadelphia Athletics. His inning came on April 27 at Fenway Park. The Red Sox were beating Connie Mack’s Athletics, 8-6, after 6 ½ innings. After a leadoff walk, Hausmann was brought in to pitch the bottom of the seventh. He walked the first two batters he faced, pitcher Earl Johnson and leadoff batter Dom DiMaggio. The bases were loaded with nobody out and Hausmann was facing Johnny Pesky. He uncorked a wild pitch, and the ninth Red Sox run scored. Then Pesky hit into a fielder’s choice, and Johnson scored. It was 10-6 with Ted Williams at the plate. But Hausmann, in the last pitch he threw in the majors, got Williams to ground into an inning-ending double play. Bill McCahan worked the bottom of the eighth. Hausmann hadn’t allowed a hit, but he was charged with one earned run. Hausmann spent the rest of the year with Buffalo.

His major-league career ERA was 4.21. His won/loss record was 9-14, all the decisions from his time with the Red Sox. As a batter, he hit .091 in 84 plate appearances. He only committed one error in 78 chances, a .987 fielding percentage.

Hausmann returned to Buffalo for 1950 (6-8, 4.69) and 1951 (2-2, 7.59).

In March 1952, Hausmann was named manager of Longview (Texas) of the Big State League, a Dallas Eagles farm club. He also pitched in 20 games and was 6-5 (3.79). The team finished seventh, but Hausmann had been replaced as skipper “early in the campaign.”13 He was called up to Dallas in late July and pitched in seven games (0-1, with an unknown ERA). It was his last year in uniform.

After baseball, Hausmann lived in Baytown, Texas, for the last 20 years of his life. He worked as a process operator for Enjay Chemical Co. He was also active in church activities at St. Joseph’s Church in Baytown.

Hausmann died at Gulf Coast Hospital in Baytown on August 29, 1972. He was only 53 years old, survived by his wife Margaret, his mother, both sisters, and his and Margaret’s son Clem and four daughters: Lois, Wanda, Carol, and Verla.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hausmann’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Felix R. McKnight, Associated Press, “Dempsey May Visit Texas,” Heraldo de Brownsville (Brownsville, Texas), July 21, 1936: 6.

2 N. Charles Wicker, “Jesuits Beat Houston in Deciding Game of Legion Series By 11 to 2,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 15, 1936: 9.

3 Hausmann, in his American League questionnaire, on file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 Ed Rumill, “Clem Hausmann Transfers Dynamiting to Diamond as Red Sox Trouble-Shooter,” Christian Science Monitor, undated newspaper clipping in Hausmann’s player file at the Hall of Fame.

5 George White, “The Sport Broadcast,” Dallas Morning News, July 22, 1939: II4.

6 Ibid.

7 Ed Rumill, “Clem Hausmann Reaches Big League Ranks Quickly,” Christian Science Monitor, June 10, 1944: 12.

8 Ibid.

9 Arthur Sampson, “Clem Hausmann Opens Sox Eyes,” Boston Herald, March 31, 1944: 32.

10 Henry McKenna, “A’s Nip Sox 7-5 to 16th,” Boston Herald, April 29, 1944: 4.

11 The phrase was Roger Birtwell’s. See “Red Sox Edge Yankees,” Boston Globe, June 20, 1945: 12.

12 Burt Whitman, “Minors Suffer Growing Pains,” Boston Herald, December 9, 1945: 89.

13 “Eagles Recall Two Players,” Dallas Morning News, July 24, 1952: 30.

Full Name

Clemens Raymond Hausmann

Born

August 17, 1919 at Houston, TX (USA)

Died

August 29, 1972 at Baytown, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.