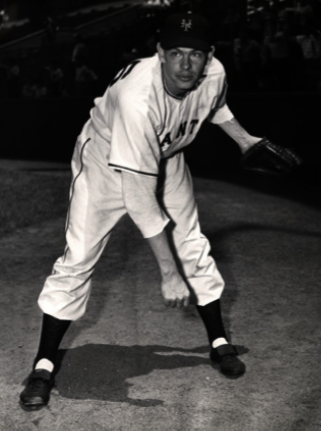

Clint Hartung

In 1947 Clint Hartung, the Hondo Hurricane, was going to be the biggest thing to hit New York baseball since Babe Ruth. Like the Babe, the 6-foot-4, 215-pound giant could pitch and hit home runs out of sight.

In 1947 Clint Hartung, the Hondo Hurricane, was going to be the biggest thing to hit New York baseball since Babe Ruth. Like the Babe, the 6-foot-4, 215-pound giant could pitch and hit home runs out of sight.

The Giants signed Hartung in 1941. He had led his high-school team in Hondo, Texas, to the Texas state championship in 1939. After a solid season in Class C in 1942, his first year in Organized Baseball, Hartung was promoted to Double-A (today’s Triple-A) Minneapolis for 1943. He was on track to make the majors by 1944, but in 1943 he was drafted and assigned to the Army Air Corps.

Hartung played on military teams while serving in the Air Corps. In 1946 he reportedly went 25-0 as a pitcher and hit .567 for the Hickam Field Bombers, based in Pearl Harbor. The Giants offered him a $35,000 bonus to sign after World War II. Hartung had signed with the Giants before the war and they should have owned his rights after the war. Contemporary sources are unclear about the reason behind the bonus, but it might best be considered a signing bonus. After many years of success the Giants had finished last in 1946, and were eager for positive publicity while rebuilding their team.

That was a decent sum for a prospect who had never played in the majors, but Clint Hartung was no ordinary prospect. His size and strength awed some of the most hard-bitten baseball men. Reporters and PR men hyped Hartung as the player who would lead the Giants out of the wilderness of the second division back to the promised land of pennants. Instead, Hartung’s failure to deliver on this hype led Bill James in his Historical Baseball Abstract to create the “Clint Hartung Award” to designate each decade’s most overhyped prospect.1 Hartung won the award for the decade of the 1940s, of course. Heady predictions in the spring of 1947 to the contrary, Hartung did not lead the team to the pennant – it was Willie Mays, Don Mueller, Sal Maglie, and of course Bobby Thomson who led the Giants when they finally captured the 1951 flag. Ironically, Hartung is probably best remembered for pinch-running for the injured Don Mueller in the crucial ninth inning of the third playoff game.

Clint Hartung was born on August 10, 1922, in the South Texas town of Hondo, about 40 miles west of San Antonio, to Robert and Thelka Hartung. Robert was a 32-year-old farm worker and Texas native. Thelka’s unusual name was given to her by her German immigrant parents 28 years earlier when she was born in Texas. Neither of Clint’s parents finished grade school. Robert worked as a farmhand for most of his life, and Thelka was a full-time housewife. Clint was their second son; they had a son Harold, four years older than Clint.

The Hartung family probably never had much money during Clint’s youth. In the 1940 census, when war production was gearing up and farm prices were rising, Robert said he worked only six weeks in 1939, although he made $150 when he worked. Harold was making $75 a week working in a haberdashery, and young Clint made $50 a week in the summertime working for the county. That makes it even more remarkable that he may have turned down money to sign with the Giants in 1946 and remained in the Army.

Clint grew to be a strapping young man. A picture of his championship high-school team in the Hondo Anvil-Herald shows Hartung at least a head taller than the rest of his teammates. John Jennings, the catcher, would cut a sponge in half and insert it into his mitt to protect his hand when he caught the pitchers. He told the San Antonio Express years later that when Hartung took the mound I’d reach back and get the other half, too. When I got done catching him, my hand would look like a pair of blue jeans, all bruised and blue.”2

In the 1939 Texas state tournament, the Owls won three straight games to win the championship. Hartung pitched and won the second game, against Adamson, 3-2. He was the only Hondo pitcher named to the All-State Team. He was not the hitting star of the tournament. That honor was claimed by Hondo third baseman Grell. When not pitching for the Owls, Hartung played the outfield and first base.

Hondo was justifiably proud of its state champions. Just about every civic organization threw them a party. At one ice-cream social, players were served a cake in the shape of a baseball. The San Antonio Missions of the Texas league invited the Owls to watch a game from the owner’s box. Hartung may not have reached his major-league playing weight of 215 pounds in high school. The Anvil-Herald described him as a “long, lean, lanky” hurler when he held Austin High School to one hit during the season.3

Major-league scouts attended the Texas State Championship, and after Hartung graduated from high school in 1941, he accepted a $500 bonus to sign with the Giants. They assigned the 19-year-old to Minneapolis and he wound up with Eau Claire of the Class C Northern League, where he had a solid inaugural season in professional baseball, hitting .358 with 12 home runs and going 3-1 as a pitcher with a 3.60 ERA.

Hartung pitched and hit very well in the service leagues during World War II. By some reports he was slated for discharge before the 1946 season. The Giants were eager to have him return to the minors for more seasoning, but Hartung, probably due to his performance in service leagues, thought he was ready to go straight to the majors. He showed his independence by re-enlisting for another year rather than go back to the minors. Other reports say Hartung re-enlisted because he hadn’t heard anything from the Giants by the time he had to make a decision about joining up. No matter what the reason, Hartung re-enlisted in 1946, dominated the army teams he faced, and the Giants offered him a big bonus to join up with them in 1947.

Garry Schumacher was the public-relations man for the New York Giants during the 1940sand had a field-level seat to the Hartung phenomenon. Schumacher said, “When Clint went into the army he was smacking the ball 450 feet or further.”4 When the players started coming home from the war, Hartung remained one of the top prospects in the Giants’ system.

The Giants finished last in the National League in 1946, with a .396 winning percentage. They were happy to report in January 1947 that Hartung had come to terms with the team. Hartung went north with the Giants in 1947, though he may have benefited from minor-league instruction. For example, Hartung in 1947 threw only a straight fastball without much of a break. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers quotes Giants catcher Walker Cooper about Hartung: “His pitch just comes in there straight. It doesn’t jump. But it is awful fast.”(Cooper held up a left hand swollen like a balloon.)“It’s awful fast.”5

The hype for Hartung started long before he arrived for spring training in 1947. He was the savior who would lead the Giants out of the wilderness of last place toward the promised pennant. New York Daily News columnist Bill Gallo, wrote, “In all my time in sports, I had never seen a ballplayer so heralded before he had played game one in the major leagues. Not DiMaggio… not Mantle… not Williams nor A-Rod or any of them. … (T)his guy, at first look, was Shoeless Joe Jackson, Ruth and Bob Feller all rolled up into one.”6

The hype before spring training was so great that Giants publicist Schumacher told the press corps in Phoenix, “Hartung’s a sucker if he ever shows up. He should go straight to Cooperstown.”7Hartung contributed to the hype by having a great spring. He homered in his first at-bat in an intrasquad game, and smacked other long drives against major-league opposition. On March 9 against the Indians Hartung hit three doubles and a single in an 8-7 victory. His last double, in the bottom of the ninth, started a game-winning rally, and he scored the winning run on a single. Hartunghit five home runs during spring training, and manager Mel Ott started him in left field, batting third, on Opening Day. Hartung went 2-for-3 with a double in a Giants loss, and two days later went 2-for-3 to help the Giants to their first win.

By the end of April Hartung was hitting .276, with no homers, two doubles, and a triple. However, he was having some difficulties tracking fly balls. In mid-May Ott put him in the pitching rotation and after Hartung won his first four starts, Ott made him exclusively a pitcher, except for occasional pinch-hitting appearances. For the season he won nine games and lost seven, with a 4.57 ERA. He batted .309 with four home runs and 13 RBIs in 34 games. (Hartung batted .333 and slugged .600 after Ott limited him to pitching. The Giants jumped from eighth place in 1946 to fourth in 1947. As a 24-year-old who proved he could pitch and hit in the major leagues, Hartung seemed poised for a good career, if not perhaps the phenomenal career that had been predicted.

Hartung did not develop and 1947 turned out to be his best year. In 1948 he pitched over 150 innings and went 8-8, but his ERA rose to 4.75, his batting average dropped to .179, and he hit no home runs. Halfway through the 1948 season, Ottwas fired as manager. His successor, Leo Durocher, kept Hartung as a pitcher through the end of the season. In 1949 he said, “So far as I can see, there’s nothing wrong with Hartung that wise counsel can’t correct.”8 Durocher assigned coach Frank Shellenback, a veteran pitcher, to room with Hartung and provide that wise counsel, but Hartung didn’t improve.

In 1949Hartunghad his first losing season with a record of 9-11 and an ERA of 5.00. Batters appeared to have solved his fastball, and he never developed a strong second pitch. As a batter in 1949 he tied his career high in homers with four, but hit only.190. That was good hitting for a pitcher, but not what had been predicted for Hartung a couple of years earlier, when he was supposed to be the second coming of Christy Mathewson and Babe Ruth.

Durocher was in the process of making over the Giants into a team that he believed could win. He traded a lot of the players from Ott’s teams, but decided to keep Hartung. Before the 1950 season he told a New York Times reporter that he thought Hartung was pitching well. Hartung did not pitch well in April, and his ERA quickly rose over 6.00. Durocher lost confidence in Hartungand didn’t pitch him at all after August.9

Hartung did hit .302in 43 at-bats in 1950 with a slugging average of .605 and three home runs. Durocher used him as a backup first baseman, right fielder, and left fielder. Hartung couldn’t push Don Mueller, Bobby Thomson, or Whitey Lockman out of a starting job, but he did make a positive contribution to a team that finished third in the National League. Meanwhile, manager Durocher continued to acquire hustling, smart ballplayers like Eddie Stanky and Alvin Dark to play second and short. He brought Sal Maglie to the pitching staff. The Giants team Durocher assembled for the 1951 team was the antithesis of the big slow-footed sluggers who started for Mel Ott.

One thing didn’t change much in 1951: Hartung’s role on the team. He was a little-used backup in 1950, and he remained in that role in 1951. Durocher started the season platooning Hartung with Mueller in right field, but he abandoned that strategy by May. Hartung didn’t pitch at all, and played in only 21 games. In this relatively small sample size, his batting average was .205 and his only extra-base hit a double. However, he did have a great seat on the bench for one of the most extraordinary seasons in baseball history, as the Giants came from 13 games back to tie the Dodgers and force a playoff.

Given that Hartung barely played during the season, it would take an emergency before Durocher would use him in the playoff. That emergency arose in the bottom of the ninth inning of the third game. The Giants, down 4-1, started a rally off an exhausted Don Newcombe. Alvin Dark and Don Mueller singled. After Monte Irvin popped up, Whitey Lockman doubled down the left-field line, scoring Dark and sending Mueller sliding into third. Mueller slid awkwardly and broke his ankle. As he was being carried off on a stretcher, Durocher sent the Hondo Hurricane in to pinch-run. That’s how Hartung was on third base when Bobby Thomson’s home run made Hartung one of the most famous pinch-runners in baseball history. With Mueller out for the World Series, Hartung pinch-hit in Game Two and started in right field in Game Five, but went 0-for-4 as the Giants lost to the Yankees.

Hartung returned to spring training with the Giants in 1952. Some writers speculated that he would be good insurance if Willie Mays was drafted. There was some talk that Hartung was learning to play second as a way to stay with the team. Durocher just had no place for Hartung on his team, and the Giants optioned him to Minneapolis. Hartung hit well as an outfielder for the Millers – .334 with 27 homeruns in 109 games – and the Giants recalled him in early August. He hit three home runs in 28 games but batted only .218 and slugged .385. On August 15 he hit home runs in both games of a doubleheader against the Boston Braves, which accounted for two-thirds of his homers for the year. The Giants finished second in what proved to be Hartung’s last major-league season.

Hartung turned 30 in 1953 and spent the entire season with Minneapolis, hitting .276 with 19 home runs. No major-league team wanted to sign a 30-year-old outfielder who had already proved he couldn’t be a major-league regular. Hartung stuck it out in the minors for another two years. Before the 1954 season the Giants sold his contract to the Havana Sugar Kings of the International League. He hit.267 with 14 home runs. In 1955 Havana sold Hartung to the Cincinnati Reds. He played for Oakland in the Pacific Coast League, Nashville in the Southern Association, and ended the season back with the Sugar Kings, where he hit .224 with five homers in 34 games. That was his last season in Organized Baseball. Hartung was 33, his skills were declining, and he returned to Texas.

Hartung took a job with an oil refinery in Sinton, Texas. He worked as a foreman and also played semipro ball for the Sinton Oilers. Hartung helped lead the Oilers to the national semipro title in the annual tournament. Hartung hit a home run that won the championship game and batted .457 over the seven-game tournament in Wichita, Kansas. The Oilers were coached by Jack Trench picking up a little extra money outside of his normal job as freshman baseball coach at the University of Texas. Trench said Hartung told him, “It was a big thrill after all his experience in the major leagues. He’s very happy in semipro ball.”10

In 1957 Giants PR man Gary Schumacher said of Hartung’s career, “Hartung had everything. He was a big, strong, good-looking kid who was just getting back from the Army. Though Hartung had never played in a big league game, he made the cover of a national magazine that spring.” That disappointment in Hartung stayed with Giants fans for several years to the point where Mario Cuomo, governor of New York, joshed in 1987 that his partner in a fantasy baseball league “proved to be the worst judge of baseball ability since a scout signed Clint Hartung.”11

Cuomo, who himself had a one-season career in the minor leagues, was not being fair. Hartung had great baseball ability, as shown by his success in the minor leagues and his domination of leagues once he was out of baseball. He didn’t have the ability to be the next Babe Ruth, but how many players do? One wonders how Hartung would have performed had he spent a little more time in the minors working on his game in 1947 and 1948 instead of riding the pines on the Giants bench, or if he had concentrated on either pitching or hitting instead of attempting both. Perhaps he would have been a better player – or again, perhaps not.

Hartung stayed in Sinton for the rest of his life. He raised his family, and tried his best to live a quiet life. At various times reporters tracked him down to ask about his career and he usually wouldn’t have much to say. In July 1983Texas Monthly published an article about Hartung at the age of 60. The reporter described Hartung as weighing 245 pounds, some 30 pounds heavier than his playing weight. His home was “bereft of baseball memorabilia.” Hartung “smoked Bel Air filters and the closest he gets to playing sports is his easy chair.”

Hartung did say that the Giants’ winning the 1951 pennant “was like knocking out Joe Louis,” but when asked if he was better as a pitcher or an outfielder, he said “neither.” Hartung went on to say that he had no regrets about his career. “When the bubble bursts, that’s it,” he said. “When it’s over, it’s over.”12

Hartung’s wife, Carolyn, said, “You gotta know Clint. He enjoyed it at the time and when it was over that was the end of it. That’s the way he thinks. He doesn’t let anything bother him. I think they should have built a monument to him in Hondo.” When Hartung heard Carolyn say that, he said, “No. They shouldn’t. Yesterday’s gone.”13

Hartung’s friends from the Giants thought he had a lot of potential, but was hurt in his career development by his lack of minor-league experience. Don Mueller, who roomed with him on the Giants, said, “Clint had all the talent in the world, but he was just a big gangly kid with long floppy arms and big ears who just wasn’t ready mentally. He should have been nurtured in the minors.”14

In 1957Hartung’scompany eliminated its national championship semipro team. He spent the rest of his post-baseball life in Sinton, working at various oil-field jobs. He raised children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Hartung died on July 7, 2010, at the age of 87. Virtually every obituary mentioned two things: the amazing hype that accompanied his major-league debut in 1947, and pinch-running for Don Mueller and scoring one of the runs that beat the Dodgers in the 1951 playoff. For himself, Hartung looked forward, not back. He told the Texas Monthly reporter in 1983, “If you wake up in the morning and it’s raining, it’s raining. If it’s sunny, then it’s sunny. I stopped worrying about things a long time ago.”15

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Durocher, Leo, with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975).

James, Bill, and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004).

James, Bill, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001).

Kahn, Roger, Memories of Summer (New York: Hyperion Books, 1997).

Smith, Red, Red Smith on Baseball (Chicago: Ivan Dee, 2000).

Hondo Anvil-Herald

Life

Look

New York Daily News

New York Times

San Antonio News Express

Sweetwater (Texas) Reporter

Texas Monthly

retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Bill James, Historical Baseball Abstract.

2 Richard Oliver, Richard Oliver, San Antonio News Express, July 18, 2010 (Hartung obituary).

3 Hondo Anvil-Herald, May 26 and June 2, 1939.

4 New York Times, December 12, 1967.

5 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, 227.

6 New York Daily News, July 23, 2010.

7 New York Times, January 17, 1951.

8 New York Times, March 3, 1950.

9 New York Times, January 17, 1951.

10 New York Times, September 4, 1957.

11 New York Times, September 22, 1977.

12 Texas Monthly, July 1983, 80-84.

13 Texas Monthly, July 1983, 85-86.

14 Texas Monthly, July 1983, 81.

15 Texas Monthly, July 1983, 82.

Full Name

Clinton Clarence Hartung

Born

August 10, 1922 at Hondo, TX (USA)

Died

July 8, 2010 at Sinton, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.