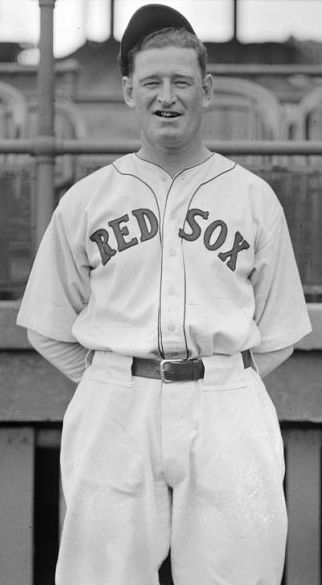

Curt Fullerton

The city of Ellsworth, Maine, is the county seat of Hancock County and the self-proclaimed “heart of Downeast Maine,” named after Oliver Ellsworth, one of the delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention that led to the founding of the United States of America. He was later a United States senator and chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The city of Ellsworth is the easternmost city in the United States.

The city of Ellsworth, Maine, is the county seat of Hancock County and the self-proclaimed “heart of Downeast Maine,” named after Oliver Ellsworth, one of the delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention that led to the founding of the United States of America. He was later a United States senator and chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The city of Ellsworth is the easternmost city in the United States.

Right-handed Boston Red Sox pitcher Curtis Fullerton, a native of Ellsworth. pitched for the Red Sox in 1921 through 1925, and then again quite a long time later, in 1933. Fullerton batted left-handed. As a major leaguer, he was an even 6 feet tall and listed at 162 pounds. Though he pitched in parts of six seasons and in 115 games, he never had a winning record.

Curtis was born on September 13, 1898. His parents were Charles Fullerton, a sea captain, and Marian Letitia (Hooper) Fullerton. Charles was born in 1870 and Marian was born in 1871. Charles and Marian had two children, Frances and Curtis. Not long after the 1900 census was taken, Charles became a painter but he died in Ellsworth of diabetes on April 2, 1901.

Marian remarried, in Ellsworth, on September 5, 1905, her second marriage, to Eugene H. Fullerton (b. 1867), his first marriage. Eugene and Charles were second cousins. Sometime after their marriage, they moved to the Noddle Island district of East Boston, Massachusetts, and by the time of the 1910 US census, he was working as some kind of engineer working in lightering (transferring cargo from one vessel to another). He later became a stationary engineer in a machine shop. Eugene and Marian had a child of their own, Edwin, born in 1907.

Curtis graduated from Emerson Grammar School and then from Mechanic Arts High School, playing baseball – pitching – in his junior and senior years. He’d played in grammar school for the Wood Island Seniors. It was with Mechanic Arts High that Curtis first pitched at Fenway Park. On June 20, 1917, he pitched his school to an 8-3 win over High School of Commerce, winning the Boston city baseball championship. Fullerton, the captain of the team, scattered six hits and it was only due to deficient defensive support (five errors) that the Commerce boys scored so many runs.1

Fullerton graduated in 1918, the final year of World War I, and spent 1918 and then 1919 working as a mechanic at a shipyard in Brooklyn. While in New York, he pitched for a semipro team headed by Guy Empey.2

By the time of the 1920 census, Fullerton was back in East Boston working as a sorter for a poultry wholesaler.

Fullerton took the train to Red Sox spring training in early March 1921, traveling out of Boston with new manager Hugh Duffy. He was described by the Boston Globe as “the young pitcher recommended by Jeff Tesreau.” 3 That would be a recommendation worthy of consideration, Tesreau having won 119 major-league games for the New York Giants and pitching in three World Series – 1912, 1913, and 1917. Tesreau headed up an independent baseball team in New York, and Fullerton pitched for Jeff Tesreau’s Bears in 1920.4

Fullerton’s big-league debut was on April 14, 1921, with two innings of relief in an 8-2 loss to the Senators in Washington. He faced 10 batters, giving up just one hit but walking two, hitting a batter, and being charged with two earned runs. He pitched two more innings the very next day, with the same result – two earned runs, this time on four hits, one of them a home run. He pitched twice more for the Red Sox, on May 20 and then – after spending most of the rest of the season with the Toronto Maple Leafs – on October 2. Both were disappointing experiences – four earned runs in three innings in the May game in Detroit, and then a complete-game 7-6 loss in New York, giving up seven runs in 8? innings. Fullerton’s ERA for the year was 8.80.

For Toronto, he was 14-10 with a 2.78 ERA. Perhaps. The Boston Herald reported his record as 17-8.5

When Fullerton arrived for spring training in Hot Springs in 1922, it was thought from the start that he’d make it. As players were still arriving for camp, Melville Webb wrote, “There seems no question that Fullerton, who finished so well with Toronto last fall and then looked so good in a game with the Yankees, will be retained, for he is going along in splendid style.”6 Indeed, he made it – and appeared in 31 games for Boston in 1922, three starts and 28 in relief. In none of the three starts was Fullerton able to complete three innings. Two of the three resulted in his being charged with losses; he was 1-4 for the season, the one win coming in the second game of a May 29 doubleheader against the visiting Washington Senators. He pitched the final three innings of the game, giving up one run in the top of the 11th, but happily seeing his teammates put across two runs in the bottom of the inning, with RBI hits by Del Pratt and Shano Collins. Fullerton’s ERA for 1922, over the 64? innings pitched, was 5.46. The Red Sox finished in last place, at 61-93. The staff ERA was 4.30, and Fullerton’s was the highest of anyone working more than three games, but he was still brought back for 1923. They needed an arm.

Fullerton impressed in spring training, earning a headline or two, but his 1923 season saw him win only twice as many games as the year before – two – while he lost nearly four times as many: He finished 2-15, though with a slightly improved earned-run average of 5.09. He worked in 37 games, starting 15, and threw a total of 143? innings. The Red Sox had a new manager in Frank Chance, but still won the same number of games as the year before – 61 – and still finished in last place, 37 games behind the pennant-winning Yankees.

It’s not really clear when it happened, but in May 1923 Nick Altrock told of a time he had seen an impressive Fullerton pitching in Boston for the House of David team. Apparently, the famous bearded traveling baseball team was short on pitchers and borrowed Fullerton from the Red Sox. Altrock didn’t know that he was on loan, and recommended him to Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators – only to find Fullerton, sans fake beard, pitching against the Senators just two weeks later in D.C.7

It was a better year for Fullerton in 1924. He lost his first decision, despite giving up just two runs, a 3-1 loss in Washington. His next two starts were complete-game wins, 7-2 and 8-2. He seemed to have been pulling it together. In mid-July, the Globe wrote, “Boston has held Fullerton for a long time, waiting for him to arrive as a contestant. …” Speaking of him and Oscar Fuhr, the article continued, “Fullerton and Fuhr have plenty of stuff – there’s no doubt of that. What has been the trouble, if the truth be told, is that neither has been quite ‘mad’ enough or serious enough to go out to deliver the goods at hand.”8 They were starting to show some fire.

August 23 was “Curtis Fullerton Day” at Fenway and he was showered with gifts from East Boston friends and admirers, including a diamond ring and a large floral horseshoe, but he got neither good luck nor sufficient support from his teammates; the Indians jumped out to an early 4-0 lead and he was replaced after three innings. The game ended 8-6, and Fullerton was charged with the loss. As the season progressed, he had added a few more wins and through the end of August was 7-5 with a 4.22 ERA.

Then came September. Fullerton started seven games and lost every one of them. The team was 9-19 for the month. Fullerton’s ERA increased a bit, to 4.38, but not all that much.

During the offseason, Fullerton lived in Boston. To keep in shape, he bowled about a dozen strings every afternoon, worked out at the East Boston YMCA, and typically ran at least a mile and a half each evening.9

Fullerton appeared in just four games in 1925 and lost three of them – despite a 3.18 ERA for the stretch. He started on April 15 and May 3 and relieved in two games in between, on April 24 and 28. On May 9 he was unconditionally released to the St. Paul Saints. The next day’s Boston Globe reported, “Pres Quinn decided it was useless to hold him longer. Going over the records he found that Fullerton had won only six games for the Boston club in the three years he has been with it, and he came to the conclusion that some of his recruits could do better than this.”10

It may have taken a change in ownership for a more open mind. Quinn owned the Red Sox until early 1933, when Tom Yawkey purchased the team.

To be fair, Quinn wasn’t necessarily as negative as this sounds; the Boston Herald reported that Quinn hoped Fullerton would find himself in the minors.11

Fullerton found St. Paul a good experience, going 15-8 in 1925. This despite a major stumble in his May 13 debut for the Saints – when the Saints came from behind to tie the game, 5-5, in the bottom of the seventh, but then Fullerton hit four Toledo Mud Hens in the top of the eighth, and surrendered four runs before the inning was over. He was rated the “truck horse” of the Saints in 1925.12

Fullerton signed with the New York Yankees late in 1925, but the New York Times suggested that the Yankees had pulled a bit of a fast one, thanks to their close ties to the St. Paul club, that the transaction had “all the elements on a ‘wash sale,’ designed to cover Fullerton up and prevent another club from drafting him from St. Paul.”13 The Yankees never invited Fullerton to spring training but let him know on February 23 that they wouldn’t be needing his services in 1926. In March he was released to Hollywood in the Pacific Coast League. The transfer to Hollywood was seen as partial compensation for Tony Lazzeri.14

Fullerton was 10-17 with a 4.34 ERA in 1926 (the Stars seemed to have trouble scoring runs in the games he pitched), and in 1927, he was 13-19 for the Stars. He pitched most of 1928 for Hollywood, too, then was traded to the Portland Beavers in early August for Elmer Smith and Johnny Couch.15 He was a combined 15-20 for the two teams, with a 3.45 ERA.

Fullerton had two full seasons for Portland in 1929 (19-18, 4.50) and 1930 (11-18, 5.90). It didn’t appear that minor-league ball was truly producing much better pitching. In 1929 he was fortunate to survive an automobile accident in San Clemente, one that took the life of Denny Williams. The Oregonian said Fullerton was one of Portland’s main three pitchers in 1929; the paper said he was “big and good-natured, easy-going and a little lazy, but when he gets hopped up he can surely pitch.” He chewed tobacco, “the bigger the quid the better the result.”16

Fullerton began 1931 with the Beavers, but was traded to Jersey City near the end of June for pitcher Kinner G. Graff, another right-hander.17 Veteran Portland sportswriter L.H. Gregory called him “Professor Fullerton” because of his “Harvard accent” and said that Fullerton was glad to be headed back East.18

Fullerton was 1-6 for the Jersey City Skeeters in 1931. He was released on September 1. He returned to Boston and left the ranks of Organized Baseball.

Semipro baseball in Boston sometimes outdrew the Red Sox. The Red Sox averaged 3,607 per game at Fenway Park in 1933, and the Boston Braves averaged 6,725 at Braves Field, but Fullerton pitched before a crowd of 9,000 at Fallon Field on August 11. Pitching for Roslindale, he threw a two-hitter that day against the Rosebuds. He threw four games in seven days for Roslindale and won three of them.

On August 21 Fullerton was signed by Eddie Collins of the Red Sox and headed to join the team in Chicago. The Red Sox were in seventh place at the time, 28 games out of first.

Just two days later, Fullerton pitched a complete game, on his first day in the majors after missing seven full seasons. It was underwhelming, a 12-1 defeat, with every one of the 12 runs earned. Fifteen hits, six bases on balls, and one hit batsman spelled defeat. Four days later, he bore another complete-game loss, this time by a 5-3 score. The two starts were his only decisions of the year; four times in September, he appeared in relief roles. He finished the season with an 8.53 ERA and the 0-2 record. The last time Fullerton had won a major-league game was August 28, 1924; he’d been saddled with an even dozen losses since that time. His big-league career ended without another win.

The Red Sox had a working agreement with the Kansas City Blues (American Association) and in December 1933, Fullerton was one of five Sox players sent there. He was released by the Red Sox in January 1934. The Associated Press seemed to have been unaware of his history; it called him “a rookie of promise.”19 He was 10-17 that year (4.76 ERA) for last-place Kansas City, and 9-11 (5.33) for the third-place Blues in 1935. In October 1934 he married Mary Mildred McGilvery.

Fullerton pitched in the Texas League for the Dallas Steers in 1936, and had a very good year (20-8, 2.72) at the somewhat lower level (Class A1, below Double-A but a notch above Class A). His 20 wins led the league. Tulsa beat out Dallas in the playoffs.

From first to worst, the 1937 Steers finished last in the league. Fullerton pitched for Dallas in 1937, but on the day the team fired manager Firpo Marberry, they also released Fullerton. He’d been sitting on the Dallas bench before a game when he learned of Marberry’s firing – and then his own release – over the loudspeaker in the park. “Did he say me?” Fullerton asked the player next to him.20 He caught on with the Galveston Buccaneers; he was a combined 8-15 (4.46) in 1937.

In 1938, now age 39, Fullerton pitched his last year in Organized Baseball, going 3-2 for the Monroe (Louisiana) White States in the Class C Cotton States League. He also appeared for the Marshall Tigers in the East Texas League and the Shreveport Sports in the Texas League.

After baseball, Fullerton returned to the Boston Naval Shipyard, where he worked as an electrician and welder.

Fullerton died in Winthrop, Massachusetts, on January 9, 1975. He was preceded in death by his wife, Mildred McGilvery Fullerton, and survived by his sister, Mrs. Frances Chase of Waltham. He is buried in Winthrop Cemetery.

Last updated: September 23, 2020 (ghw)

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Fullerton’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Dick Beverage for some of Fullerton’s Pacific Coast League data.

Notes

1 Christian Science Monitor, June 21, 1917.

2 Boston Globe, August 21, 1924.

3 Boston Globe, March 6, 1921.

4 Boston Globe, August 21, 1924.

5 Boston Herald, September 19, 1921. The 14-10 mark is as reported on baseball-reference.com.

6 Boston Globe, March 15, 1922.

7 Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, May 13, 1923.

8 Boston Globe, July 11, 1924.

9 Boston Globe, January 23, 1925.

10 Boston Globe, May 10, 1925.

11 Boston Herald, May 10, 1925.

12 The Sporting News, March 4, 1926.

13 The New York Times, February 24, 1926.

14 Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1926.

15 The Oregonian (Portland), August 12, 1928.

16 The Oregonian, January 28, 1930.

17 Idaho Statesman (Boise), June 25, 1931.

18 The Oregonian, June 25, 1931.

19 See the AP story, which ran in several newspapers, including the Boston Herald, on December 14, 1933.

20 The Sporting News, July 22, 1937.

Full Name

Curtis Hooper Fullerton

Born

September 13, 1898 at Ellsworth, ME (USA)

Died

January 9, 1975 at Winthrop, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.