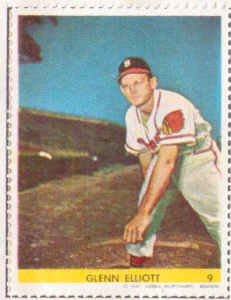

Glenn Elliott

The lesser known and less accomplished of the two unrelated Elliotts who played for the Boston Braves in the late 1940s, Glenn “Lefty” Elliott is best remembered because he wore eyeglasses on the ballfield and surrendered Jackie Robinson’s first major-league base hit.

The lesser known and less accomplished of the two unrelated Elliotts who played for the Boston Braves in the late 1940s, Glenn “Lefty” Elliott is best remembered because he wore eyeglasses on the ballfield and surrendered Jackie Robinson’s first major-league base hit.

A 5’10”, 170-pound soft tosser from Oregon, “Silent Glenn” Elliott spent parts of three seasons as a relief pitcher for the Braves. From 1947 to 1949 he pitched in 34 National League games, posted a 4-5 record, and compiled a 4.08 earned run average in 90 1/3 innings. In Boston’s 1948 NL championship season, he gave up five hits and a walk in his only appearance, but allowed just one run in three innings and was credited with a win. At the plate, he was a switch-hitter who couldn’t hit from either side; he singled safely just twice in 21 big-league at-bats.

But the crafty lefty enjoyed a lengthy and successful career as a starting pitcher in the minor leagues. Elliott posted a 150-139 record and a 3.47 ERA for five franchises from 1942 to ’56. He appeared in 426 contests — mostly with the Braves’ Milwaukee farm club or in the Pacific Coast League, served up 2,479 hits in 2,475 innings, walked 692, and struck out 1,229. A graduate of Oregon State College, the scholarly southpaw taught school during the offseason, and worked as a carpenter, sold cars, farmed, and served as a scout for the Phillies before his untimely death from a brain tumor.

Herbert Glenn Elliott was born on the first anniversary of the end of World War I, November 11, 1919, at Sapulpa, Oklahoma, the youngest of Jacob and Julia Goodman Elliott’s seven children. Jacob, born in 1868, was a ranch-hand whose family was among the first white settlers in Southern California’s Imperial Valley. He journeyed to work with his brother in Oklahoma, and met and married Julia, a Cherokee Indian who was born in Kansas in 1892 (Glenn’s Native American heritage was seldom if ever mentioned during his career). The couple produced four daughters and two sons who survived childhood and another son who did not. In 1922, the Elliotts (including young Glenn) moved to California, and eventually settled near Bakersfield. By 1935, Jacob and Julia had split up, and she and her younger children followed an older daughter to Myrtle Creek, a small mill town in a heavily forested region of southwestern Oregon.

A natural lefty forced to write right-handed, Elliott arrived in the Pacific Northwest at the age of 15, and earned letters in baseball, football, and basketball at Myrtle Creek High. He pitched a pair of no-hitters for his high school squad and two more for his American Legion team. Scouted by the Red Sox, Dodgers, Reds, and Yankees, he was regarded as one of the nation’s top pro prospects, but instead of signing, elected to attend Oregon State College (now Oregon State University) in Corvallis. Freshmen weren’t eligible to play in 1939, but Elliott earned a letter as a sophomore in 1940 when the Beavers posted a 19-5 record and won the Northern Division of the Pacific Coast Conference for longtime coach Ralph Coleman. Elliott lettered in 1941 when Oregon State posted a 15-10 mark, and in 1942, when the Beavers finished 14-8.

After Oregon State’s 1942 season ended, Elliott played semipro baseball before he signed a pro contract with Seattle of the Pacific Coast League. The Rainiers farmed him to Vancouver of the Class B Western International League, where the lefty posted a 7-3 record and a 3.35 ERA in 13 games in the summer of ’42 despite a sore and twisted arm. He had injured the arm at Oregon State on a day when he pitched in a cold rain. It bothered him the rest of his collegiate career, robbing him of some velocity, and his efforts to compensate further damaged the limb. “While with Vancouver, his arm became so crooked it was difficult for him to pitch and Manager Don Osborne suggested that he take up bowling to try to straighten out his salary wing,” the 1947 Boston Braves Sketch Book later revealed. “After about a year his arm was well straightened out and the soreness gradually vanished.”

Seattle recalled Elliott, who compiled a 6-7 record with a 3.84 ERA in 24 games with his “bowling straightened” left arm in 1943. Married briefly, divorced, and the father of a baby daughter, Barbara Ann, Elliott continued to attend classes at Oregon State in the offseason. The next spring, he graduated with a degree in biological sciences, then turned in a 6-6 record with a 3.43 ERA in 25 games for the 1944 Rainiers. “His arm had troubled him so much during the period when it was crooked that he spent most of his time as a relief pitcher once it had been straightened out,” the Braves Sketch Book reported.

By 1945, he was primarily a Seattle starter, his workload continued to increase, and he went 14-12 with a 3.81 ERA. He took a couple of giant steps forward the next year, first to the altar, where he wed childhood sweetheart Audrey Joyce Ady (known by Joyce) of Myrtle Creek on May 15, 1946, and then on the field. Though he compiled just a 12-13 record for the last-place Rainiers in 1946, he pitched 235 innings, 39 more than the season before, had a much stingier ERA (3.26), struck out 56 more hitters (142), and walked just seven more (74).

At the end of the season, the Braves purchased Elliott from Seattle on a conditional basis. After an offseason spent teaching in Myrtle Creek, the bespectacled southpaw allowed just five runs in 24 spring training innings, and was named Boston’s outstanding rookie of the camp by The Sporting News. But as the team played exhibition games on its way north, Elliott began to falter, and failed to find a foothold in the starting rotation. On Opening Day 1947, Elliott was in Billy Southworth’s bullpen when Boston’s Johnny Sain and two other pitchers suffered a 5-3 loss at Brooklyn. Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in the major leagues in the 20th century, went 0-for-3 at the plate, but reached on a misplayed sacrifice bunt and scored the winning run in his debut as a Dodger.

Two days later, on Thursday, April 17, Elliott made his first major-league appearance at the age of 27 before 10,252 at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. With the Braves trailing 7-2, Elliott made his entrance in the bottom of the fourth inning and surrendered three runs. The following inning, Robinson reached on a bunt single, the first hit of his major-league career. (Robinson bunted 42 times in 1947; 19 went for hits). Elliott rebounded to pitch a scoreless fifth inning; then yielded to pinch-hitter Tommy Holmes. In his two-inning stint, Elliott allowed three hits and a pair of walks and recorded one strikeout.

After he gave up Robinson’s initial hit, Elliott experienced a variety of reactions. “He would tell us that some people jokingly told him, ‘Thanks to you, the color barrier was broken,’” Glenn’s daughter Taraleen Elliott Stymer remembered. “For other people it wasn’t very funny. They were serious. ‘It’s your fault.’ The story that we heard was that Jackie Robinson’s career was a little iffy at that point, and that was kind of a last shot and if he didn’t make it [with Brooklyn], he wasn’t going to make it [in the major leagues] and that [the bunt single] was kind of what gave him the edge.” Elliott didn’t dwell on the reaction, and didn’t question whether Robinson should be in the big leagues. “I think he was more embarrassed that he got attention for it,” Taraleen remembered. “He certainly didn’t think it was any big deal. He said that if people could play ball, they should play ball. There was a fair amount of ill will at first; then folks realized [Robinson] was a good ballplayer and that was all they cared about after a while.”

Two days after he gave up Robinson’s historic hit, Elliott allowed just four safeties in 5 2/3 innings against the Phillies in relief of Red Barrett at Braves Field. And though he surrendered a two-run homer to Andy Seminick, he struck out three and collected his only hit of the season in a 9-2 defeat. On April 27, Elliott suffered a loss, his lone decision of the campaign, when he served up a ninth-inning Jim Tabor home run in the second game of a doubleheader at Philadelphia. In the first game of the twin bill, he pitched the ninth inning of a 5-4 loss. He was inconsistent in May, however, and by early June he had allowed 18 hits, 11 walks and 10 runs in 19 innings, to post a lackluster 4.74 ERA for Southworth’s squad.

The Braves shipped Elliott to their farm team at Milwaukee, and for the next four months, Elliott pitched well. Inserted into the rotation by manager Nick Cullop and backed by a keystone combination of second baseman Danny Murtaugh and shortstop Alvin Dark, Elliott compiled a 14-5 record to lead the Brewers to a third-place finish in the American Association regular season standings. Cullop encouraged Elliott to add a screwball to his arsenal, and the results were immediate. He pitched two shutouts, posted a 3.78 ERA, struck out 75, and walked just 45 in 138 innings to earn a spot on the league’s All-Star Team. He earned two victories in the American Association playoffs when the Brewers bested the Kansas City Blues four games to two and the Louisville Colonels four games to three. And to cap off the season, Elliott pitched a complete game 4-1 victory in the deciding game of the 1947 Junior World Series as Milwaukee defeated the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League in seven contests. In that championship finale, “the wily southpaw” scattered nine hits and no walks, and allowed only a ninth-inning home run.

After he played winter ball in Puerto Rico, Elliott was back with the Brewers (who listed his birth year as 1922), in 1948. He posted a 14-7 record and a 3.76 ERA, the best in the American Association. He surrendered 181 hits and 73 walks and struck out 125 in 189 innings; a performance that earned him a callback to pennant-contending Boston the first week in September “for immediate delivery.” The move irritated fans of the second-place Brewers, and seemed worse when Milwaukee lost in the first round of the AA playoffs.

Elliott, meanwhile, made just one appearance down the stretch for the “Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain” Braves. With Boston tied for first with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Glenn was tabbed by Southworth to start the second game of a September 1 double header at Cincinnati. Staked to a 3-0 lead by the Braves in the first inning, Elliott surrendered a single run in the bottom of the first, then shut out the Reds in the second and third. In the top of the fourth inning, he grounded out, collided with Cincy first baseman Ted Kluszewski, and had to leave the game with a 4-1 lead. Elliott had allowed five hits, the run, and two strikeouts in his three-inning stint, and was awarded a win in accordance with the rules in effect at the time. It turned out to be his only outing for the 1948 Braves; meanwhile Boston’s “other” Elliott, defending NL Most Valuable Player Bob Elliott, led the Braves to the World Series.

Both Elliotts were back with Boston in 1949, and Glenn compiled a 3-4 record with a 3.95 ERA. He appeared in 22 games, hurled 68 1/3 innings, and gave up 70 hits. The soft-tossing southpaw walked just 27, but struck out only 15. He made his final big-league appearance on Thursday, September 29, against Brooklyn, in relief of Spahn in a 9-2 loss at Braves Field.

Elliott attended spring training with the Braves in 1950, but was optioned to Milwaukee before the season started. He was less effective for the Brewers than before, posting an 11-12 mark with a 4.50 ERA. He did manage to draw one of two walks given up when Louisville’s Bob Alexander pitched a 5-0 no-hitter against the Brewers on July 29, but that wasn’t enough to save his job. In August, the Braves sent Elliott to Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League along with cash and a player to be named later in exchange for pitching prospect Max Surkont.

The nearsighted portsider spent the rest of his playing career in the PCL. He appeared in 11 games for Sacramento the remainder of that season and compiled a 3-4 record and a 3.21 ERA. He posted a 15-14 record and a 3.05 earned run average in 33 games for the Solons in 1951, but the seventh-place squad struggled to make ends meet. Sacramento was engaged in a working agreement with the Chicago White Sox, but the parent team terminated it at the end of the season. “In canceling their working agreement with Sacramento recently,” The Sporting News reported, “the Chicago White Sox paved the way for the Solons to peddle their two bespectacled pitching aces, Lefty Glenn Elliott and Rookie Walt Clough, both of whom will be draft eligible. The Chisox had first refusal on the two players, the first for $35,000 and the second for $30,000. Solon officials hope to use Elliott and Clough as bait for a new working agreement.” Manager Joe Gordon speculated that Elliott would be a steal at $25,000, but there were no takers, even at the bargain price.

That made Elliott eligible for the annual Rule 5 draft of minor-league players, and on December 1, the lefty was the sixth player selected, claimed for $10,000 by the Washington Senators. “I have to respect what Joe Gordon, the Sacramento manager, told me about Elliott,” Senators skipper Bucky Harris told The Sporting News. “He assured me that Elliott could win in the majors, that he is all business out there and has amazing control for a left-hander. ‘If Elliott isn’t a big winner for you, Bucky, I give up.’ Those were Joe’s words.” Despite the promise, Elliott’s final audition for a big-league roster spot went poorly. He suffered from a sore shoulder from the start of spring training, and on March 12, he was smacked on the head by a Mickey Vernon line drive. The Senators absorbed a $2,500 loss when they sold Elliott back to Sacramento for $7,500 before the 1952 season started.

Washington may have given up too soon. Elliott, who joined former Boston Braves teammate Bob Sturgeon in Sacramento, bounced back from the sore shoulder to pitch 254 innings in 40 appearances and struck out 117 batters. He went just 12-18 for the struggling Solons despite a 3.19 ERA, and at the end of the season Sacramento traded Elliott and pitcher Orval Grove to Portland for outfielder Joe Brovia and pitcher Marino Pieretti. At Portland, he was reunited with another former Braves teammate, Jim Russell. Elliott played winter ball for Hermosillo in the Mexican League, signed late in the spring of 1953 with Portland, then posted a 12-14 record with a career best 3.02 ERA over 227 innings in 38 games.

Limited to 28 appearances in 1954 and forced to wear a tightly stitched jacket when he did pitch because of a sore sacroiliac (the joint between the hips and spine), Elliott still managed a 12-15 record and a 3.29 ERA. He appeared in 32 games in 1955, mostly in relief, and posted a 7-6 record and a 3.28 ERA. He was released by the Beavers over the winter, and at the end of the school year found work as a carpenter in Portland, before Sacramento brought him back in late June of 1956. At the age of 36, he appeared in 20 games the rest of the way for the Solons and compiled a 5-3 record.

Elliott was involved in an automobile accident over the winter, and reported to Sacramento’s spring training in ’57 with an injured arm that prompted him to return home to Myrtle Creek before the season. The Solons tried to persuade him to join them in June, but the arm hadn’t healed and Elliott was by then also nursing a bruised leg. He decided to call it a career.

His pitching days behind him, Elliott sold cars, played golf, and watched his favorite spectator sport — basketball. He became the Pacific Northwest scout for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1960, a position he held for the rest of his life. He went to spring training each year, then hit the road in search of prospects. Among the players he signed for Philadelphia was pitcher Rick Wise, who won 188 games in 18 major-league seasons.

In 1964, Glenn and Joyce moved their six children to Stafford, 15 miles south of Portland, where the family farmed and raised livestock. Elliott hunted, fished, collected stray animals — including a skunk — dabbled with breeding Appaloosa horses, and kept his left arm limber. “He used to throw to my mom,” his daughter Taraleen remembered. “My mom was a really tiny person. But she would be out there with a catcher’s glove, catching him.”

“Silent Glenn” also welcomed friends from baseball to the family farm. “Generally he was really quiet,” Taraleen recalled. “He was not a real outgoing person, unless you got to know him. As quiet as he was, he and mom both liked to entertain. Lots of baseball people came out to the farm.” Among those who visited were former Braves teammate and lifelong friend Johnny Sain, and his wife, Dorothy, and Portland Beavers announcer Bob Blackburn and Oregon Journal writer Bill Mylslur and their families. Taraleen also recalled that the kids looked forward to their annual shipment of chewing gum and baseball cards from the Topps Company.

The family’s tranquility was shattered by cancer. Just four months after he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, Herbert Glenn Elliott died at Providence Hospital in Portland on July 27, 1969, at the age of 49 (though some media outlets reported his age as 46). “It was a complete shock for the whole family. We had to sell the farm,” Taraleen remembered. “My mother, who had been a homemaker, worked two jobs and moved the family to Corvallis, and rented a house near campus. She knew that we were all either in college or going to go to college.” Well after she made sure that each of her six children had the opportunity to attend Oregon State University, Audrey Joyce Ady Elliott died at 71 of complications from Alzheimer’s disease on August 28, 1993. She was buried at Odd Fellows Cemetery in Myrtle Creek, where Glenn had been laid to rest 24 years earlier.

The couple are survived by sons Jock (born in 1948) of Albany, Kip (1950) of Corvallis, and Bart (1954) of Redmond, daughters Colleen (1951) Thomas of West Linn, Shalleen (1953) Fruits of Tarpon Springs, Florida, and Taraleen (1957) of Philomath, and Glenn’s daughter from his first marriage (Joyce’s stepdaughter), Barbara Ann Cross of California, and a number of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Nearly a half-century after his untimely death, the bespectacled lefty is remembered in his adopted state. The Glenn Elliott Memorial Trophy has for many years been awarded to the Most Valuable Player in Oregon’s Metro State All-Star Baseball Game, and in 1991 Elliott was named to the Oregon State University Hall of Fame. The school’s website states: “Glenn was one of the most feared pitchers in collegiate baseball in his era.” Though his major-league career and his life were short, Glenn Elliott contributed a win to the Boston Braves 1948 pennant pursuit, and made his mark as a minor leaguer, a scout, and a devoted family man.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Eig, Jonathan, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007)

Gillette, Gary, and Pete Palmer, The 2005 ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Sterling, 2005)

Hamann, Rex, and Bob Koehler, The American Association Milwaukee Brewers (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2004)

Lee, Bill, The Baseball Necrology: The Post-Baseball Lives and Deaths of Over 7,600 Major League Players and Others (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003)

Neft, David S., Richard Cohen, and Michael Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball 2004. 24th Edition (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004)

Peary, Danny, We Played the Game: Memories of Baseball’s Greatest Era (New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, Inc., 1994)

Sugar, Bert Randoph, Baseball’s 50 Greatest Games (New York: Weiser & Weiser, Inc., 1986)

2007 Oregon State University Baseball Media Guide, Oregon State University Sports Information Department, Corvallis, Oregon.

1947 Boston Braves Sketch Book

1947 Milwaukee Brewers Sketch Book

1948 Milwaukee Brewers Sketch Book

The Sporting News

Portland Oregonian.

Pat Doyle, Professional Baseball Players Database

Interview with Taraleen Elliott Stymer by Doug Skipper, August 2007.

Web Sites

www.baseball-almanac.com

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.minorleaguebaseball.com

www.mlb.com

Full Name

Herbert Glenn Elliott

Born

November 11, 1919 at Sapulpa, OK (USA)

Died

July 27, 1969 at Portland, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.